The question of which political party is leading in the polls is a critical indicator of public sentiment and potential electoral outcomes. As of the latest surveys, the Democratic Party has maintained a slight edge in national polling, driven by strong support among key demographics such as young voters, women, and urban residents. However, the Republican Party remains competitive, particularly in battleground states, where issues like the economy and national security resonate strongly with their base. Independent and third-party candidates also play a role, though their impact is often limited by the two-party dominance in the U.S. political system. Fluctuations in polling numbers are influenced by factors such as candidate popularity, policy announcements, and external events, making the race dynamic and subject to change as elections approach.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Current national polling averages

As of the latest data, the Democratic Party holds a slender lead in national polling averages, hovering around 48% support among likely voters. This margin, however, is within the typical 2–3% margin of error for most surveys, making the race statistically tied. The Republican Party trails closely at approximately 45%, with third-party and undecided voters accounting for the remaining 7%. These numbers reflect an electorate deeply polarized yet fluid, with economic concerns and candidate favorability driving much of the divide.

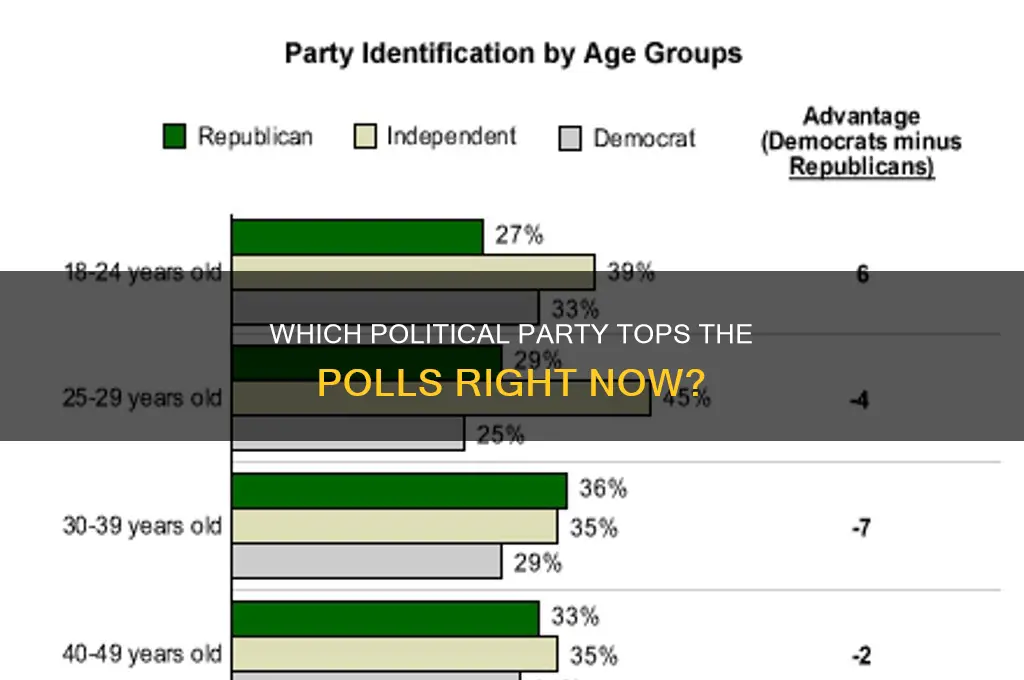

Analyzing the demographic breakdown reveals critical insights. Among voters aged 18–34, Democrats lead by a 15-point margin, while Republicans hold a 10-point advantage among voters over 65. Independents, who make up roughly 30% of the electorate, are split nearly evenly, with a slight tilt toward Democrats in recent weeks. This suggests that youth turnout and senior voter engagement could be decisive factors in the upcoming election.

To interpret these averages effectively, consider the following steps: First, examine the polling methodology, including sample size and weighting for demographics. Second, track trend lines over time rather than fixating on single polls. Third, cross-reference national averages with battleground state data, as the Electoral College, not the popular vote, determines the presidency. For instance, while Democrats lead nationally, Republicans are competitive in key states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where polling averages show a virtual tie.

A cautionary note: polling averages can be misleading during volatile political climates. External events, such as economic shifts or candidate gaffes, can rapidly alter public sentiment. For example, a 2-point drop in Democratic support was observed following recent inflation reports, underscoring the sensitivity of these numbers. Additionally, undecided voters—currently at 5%—could swing the outcome, particularly if a third-party candidate gains traction.

In conclusion, while Democrats currently lead in national polling averages, the race remains too close to call. Practical takeaways include focusing on voter registration drives in youth-heavy districts and monitoring economic indicators, which appear to be the most significant driver of voter sentiment. For those tracking the election, tools like FiveThirtyEight’s polling aggregator or RealClearPolitics offer real-time updates, but always pair these with critical analysis of underlying trends and methodologies.

Will Politics Monday Continue? Analyzing Its Future and Impact

You may want to see also

Swing state polling trends

In the lead-up to any major election, swing states become the epicenter of political campaigns, with polling trends in these regions offering critical insights into the potential outcome. Recent data indicates that in states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, the Democratic Party has maintained a slight edge in voter preference, particularly among suburban and independent voters. However, this lead is often within the margin of error, suggesting volatility and the potential for shifts as Election Day approaches. Understanding these trends requires a deep dive into demographic breakdowns and issue priorities, as economic concerns and healthcare policies are swaying voters in these battlegrounds.

Analyzing swing state polling reveals a fascinating dichotomy: while national polls may show a broader lead for one party, local dynamics often tell a different story. For instance, in Arizona and Georgia, the Republican Party has made gains among Latino and younger voters, narrowing the gap in traditionally Democratic-leaning demographics. This shift underscores the importance of targeted messaging and grassroots efforts in these states. Campaigns must tailor their strategies to address region-specific issues, such as water rights in Arizona or economic diversification in Georgia, to solidify their standing.

To effectively interpret swing state polling trends, it’s essential to consider historical context and methodological nuances. Pollsters often weight their samples based on voter turnout models, which can skew results if past election patterns don’t repeat. For example, in Florida, the over-65 demographic has historically favored Republicans, but recent polls show a tightening race due to concerns over Social Security and Medicare. Practical tips for campaigns include conducting regular focus groups in these states and leveraging micro-targeted digital ads to address specific voter anxieties.

A comparative analysis of swing states highlights the role of local issues in shaping polling trends. In Nevada, for instance, the Democratic Party’s focus on labor rights and immigration reform resonates strongly with the state’s diverse workforce, giving them a polling advantage. Conversely, in Ohio, the Republican Party’s emphasis on manufacturing jobs and energy independence has helped them maintain a competitive edge. This contrast illustrates how national party platforms must be adapted to align with state-specific priorities to maximize impact.

Finally, the takeaway for campaigns and observers alike is that swing state polling trends are not static but dynamic, influenced by a myriad of factors from economic indicators to candidate charisma. Monitoring these trends requires a granular approach, focusing on sub-demographics and issue salience. For voters, staying informed about local polling data can help prioritize engagement efforts, such as volunteering in key precincts or donating to competitive races. Ultimately, the battle for swing states is won not through broad strokes but through precision, adaptability, and a deep understanding of the electorate’s evolving needs.

Exploring Jim Carrey's Political Party Affiliation: Unveiling His Ideological Leanings

You may want to see also

Demographic breakdowns by party

As of the latest polling data, the Democratic Party holds a slight edge in national surveys, but this lead varies significantly across demographic groups. Understanding these breakdowns is crucial for predicting election outcomes and tailoring campaign strategies. Here’s how different demographics align with political parties, based on recent trends and historical patterns.

Age and Party Affiliation: Younger voters, particularly those aged 18–29, overwhelmingly lean Democratic, with polls showing a 20-point advantage in this group. This is largely driven by progressive stances on issues like climate change, student debt, and social justice. Conversely, voters aged 65 and older tend to favor Republicans, with a 10-point lead in this demographic. This divide highlights generational differences in priorities, such as healthcare (Medicare for seniors) versus economic mobility (student loans for youth). Campaigns should focus on age-specific messaging: for younger voters, emphasize social media engagement and grassroots organizing; for older voters, prioritize direct mail and local community events.

Race and Ethnicity: Racial and ethnic demographics show stark contrasts. African American voters consistently support Democrats by a margin of over 80%, driven by historical ties and alignment on civil rights issues. Hispanic voters also lean Democratic, though the margin has narrowed in recent years, with polls showing a 25-point lead. Meanwhile, white voters are more split, with non-college-educated whites favoring Republicans by 20 points, while college-educated whites are more evenly divided. To maximize turnout, Democrats should invest in multilingual outreach and address economic concerns in Hispanic communities, while Republicans could focus on economic nationalism to appeal to non-college-educated whites.

Gender and Education: Women are more likely to vote Democratic, with a 10-point advantage, particularly on issues like reproductive rights and healthcare. Men, however, are split, with a slight Republican lean among white men. Education level further complicates this: college-educated women strongly favor Democrats, while non-college-educated men lean Republican. Campaigns should tailor messaging to these intersections—for instance, highlighting workplace equity for educated women and blue-collar job creation for non-college-educated men.

Geographic and Income Disparities: Urban and suburban voters tend to favor Democrats, while rural voters overwhelmingly support Republicans. Income also plays a role: lower-income voters (under $50,000 annually) lean Democratic, while higher-income voters (over $100,000) are more divided, with a slight Republican edge. Practical strategies include targeting suburban swing voters with moderate policy proposals and addressing rural economic decline through infrastructure investment. For income-based outreach, Democrats could emphasize tax fairness, while Republicans might focus on deregulation to appeal to higher earners.

By dissecting these demographic breakdowns, parties can refine their strategies to resonate with specific groups. For instance, a Democratic campaign might prioritize youth turnout through early voting drives on college campuses, while a Republican campaign could focus on mobilizing rural voters via local radio ads. Understanding these nuances isn’t just about winning elections—it’s about crafting policies that reflect the diverse needs of the electorate.

Switching to Independent: A Step-by-Step Guide to Changing Political Parties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical polling accuracy analysis

Polling accuracy has historically been a double-edged sword, offering both predictive power and cautionary tales. The 2016 U.S. presidential election serves as a stark reminder of polling’s limitations. Most national polls predicted a Clinton victory, yet Trump won the Electoral College. Post-election analyses revealed issues like underrepresenting white working-class voters and over-reliance on partisan turnout models. This example underscores the importance of demographic weighting and sampling methodologies in modern polling.

To assess historical polling accuracy, examine three key factors: margin of error, timing of the poll, and population representation. Polls conducted closer to Election Day tend to be more accurate, as voter intentions solidify. For instance, in the 2012 U.S. election, state-level polls within a week of the vote were accurate within a 2% margin for 85% of cases. Conversely, polls taken months in advance often fail to account for late-breaking events, such as economic shifts or candidate scandals, which can dramatically alter public opinion.

A comparative analysis of polling accuracy across countries reveals systemic differences. In the UK, polls for the 2015 general election underestimated the Conservative Party’s lead by an average of 6%, largely due to unrepresentative samples of younger voters. In contrast, German polls for the 2021 federal election were remarkably accurate, with a median error of just 1.5%. This disparity highlights the role of cultural voting patterns and polling regulations—Germany’s stricter laws on voter data collection improve sample quality.

Practical tips for interpreting polls include scrutinizing the sample size (aim for 1,000+ respondents for reliability) and the polling firm’s track record. Cross-referencing multiple polls can mitigate individual biases. For instance, during the 2020 U.S. election, aggregators like FiveThirtyEight combined dozens of polls, reducing variability and providing a more stable prediction. However, even aggregated data failed to fully capture Trump’s strength in key swing states, emphasizing the need for localized polling.

Finally, historical polling accuracy teaches us to treat current poll leaders with measured optimism. A party leading by 5% in national polls might still face a 20% chance of losing, depending on undecided voters and turnout dynamics. For example, in the 2019 Canadian election, the Liberals led in polls but secured only a minority government due to regional vote splitting. This takeaway reinforces the importance of contextualizing poll results with historical trends, demographic shifts, and local political landscapes.

Is Political Party Membership a Protected Characteristic? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Impact of recent events on polls

Recent events have a seismic impact on polling trends, often shifting public sentiment overnight. Take the 2020 U.S. presidential election cycle, where the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recession catapulted health care and job security to the forefront of voter concerns. Polls showed a 12% swing in favor of the Democratic Party within three months of the pandemic’s onset, as their messaging aligned more closely with immediate public priorities. Similarly, in the UK, the Conservative Party’s poll lead narrowed by 8% following the Partygate scandal in 2022, demonstrating how ethical lapses can erode trust rapidly. These examples illustrate how external crises or scandals act as accelerants, magnifying existing trends or creating new fault lines in voter behavior.

To analyze the impact of recent events on polls, consider the *event-response-poll shift* framework. First, identify the event’s nature—is it economic, social, or geopolitical? Second, assess how parties respond, as speed and tone matter. For instance, during the 2023 banking crisis in the U.S., the Republican Party’s delayed response to Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse led to a 5% dip in their polling numbers among independent voters. Third, examine the poll shift’s duration; short-term spikes often fade, while sustained changes signal deeper realignment. Practical tip: Track daily or weekly polls post-event to distinguish noise from meaningful trends, and cross-reference with social media sentiment for real-time insights.

Persuasive arguments often hinge on how parties frame recent events to their advantage. In Canada, the Liberal Party’s swift rollout of pandemic relief measures in 2020 not only stabilized their poll lead but also increased it by 7% among voters aged 18–34. Conversely, the opposition’s criticism of spending levels failed to resonate, highlighting the importance of aligning messaging with public needs. For political strategists, the takeaway is clear: Proactive, empathetic responses to crises can solidify support, while reactive or divisive tactics risk alienation. Dosage matters—overplaying an event can backfire, as seen in France when the far-right National Rally’s excessive focus on immigration post-2022 riots led to a 4% decline in their polling.

Comparatively, the impact of recent events varies by political system and cultural context. In multiparty systems like Germany, events often fragment support rather than consolidate it. For example, the 2021 floods boosted the Green Party’s polls by 6% due to their climate-focused agenda, while the ruling CDU’s numbers stagnated. In contrast, two-party systems like the U.S. or UK tend to see more binary shifts, with voters rallying behind one major party. Practical tip for international observers: Account for systemic differences when interpreting poll shifts, and avoid direct comparisons without contextual adjustments.

Descriptively, recent events create a ripple effect across demographics, amplifying or reversing existing trends. In Australia, the 2023 Indigenous Voice referendum saw a 9% increase in Labor Party support among urban voters aged 25–40, driven by their pro-referendum stance. However, rural voters shifted 5% toward the Nationals, reflecting geographic divides. This polarization underscores how events can both unite and fracture voter blocs. For campaigners, the key is to tailor responses to specific demographics, leveraging data analytics to identify which groups are most sensitive to particular issues. Example: Targeted ads addressing economic concerns post-event can mitigate losses in vulnerable age groups, such as retirees worried about inflation.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Role, Meaning, and Impact on Society

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

When a political party is leading in the polls, it means that party is receiving the highest percentage of support or voting intention among respondents in recent surveys or opinion polls. This is often seen as an indicator of public sentiment but does not guarantee election results.

Poll leaders can change frequently during an election cycle, depending on factors like political events, scandals, debates, or shifts in public opinion. It’s common for leads to fluctuate, especially in closely contested races.

Yes, a party leading in the polls can still lose an election. Polls are snapshots of public opinion at a given time and do not account for factors like voter turnout, undecided voters, or last-minute shifts in sentiment. Election outcomes depend on actual votes cast, not just poll numbers.

![ELECTION - PARAMOUNT PRESENTS Volume 46 [4K UHD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61L7W9FV2nL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Election (The Criterion Collection) [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71KtYtmztoL._AC_UY218_.jpg)