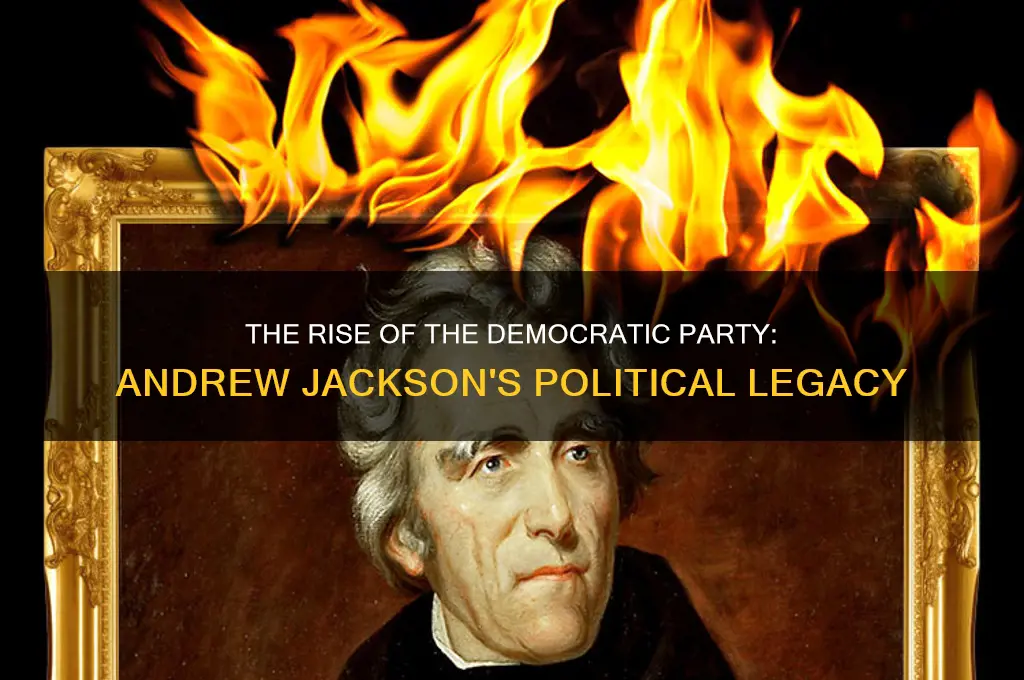

The Democratic Party, one of the two major political parties in the United States, traces its origins to the presidency and political legacy of Andrew Jackson. Emerging in the late 1820s, the party was initially known as the Democratic-Republican Party, a faction that broke away from the earlier Democratic-Republican Party founded by Thomas Jefferson. Jackson’s populist appeal, his advocacy for the common man, and his opposition to elite institutions like the Second Bank of the United States galvanized support for what would become the modern Democratic Party. His election as president in 1828 marked the party’s formal consolidation, and it has since evolved into a major force in American politics, shaping policies and ideologies that continue to influence the nation today.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Founder | Andrew Jackson |

| Party Name | Democratic Party (originally known as the Democratic-Republican Party) |

| Formation Year | 1828 |

| Ideological Roots | Jacksonian Democracy, Populism, States' Rights |

| Core Principles | Limited Federal Government, Opposition to Elites, Expansion of Suffrage |

| Key Policies (Historical) | Opposition to National Bank, Support for Manifest Destiny, Indian Removal |

| Modern Alignment | Center-Left to Left-Wing (in contemporary U.S. politics) |

| Symbol | Donkey (unofficial but widely associated) |

| Current Leadership | Varies (e.g., President, DNC Chair, Congressional Leaders) |

| Base of Support | Urban, Suburban, and Rural Voters; Diverse Demographics |

| Notable Figures | Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson, Barack Obama, Joe Biden |

| Platform (2023) | Healthcare Expansion, Climate Action, Social Justice, Economic Equality |

| Global Alignment | Social Liberalism, Progressive Policies |

Explore related products

$21.95

What You'll Learn

- Democratic Party Origins: Founded by Andrew Jackson's supporters in the 1820s, emphasizing democracy and states' rights

- Jackson's Influence: His populist appeal and opposition to elites shaped the party's early identity

- Key Principles: Focused on limited federal government, agrarian interests, and individual liberty

- Opposition to Whigs: Formed as a counter to the Whig Party, led by Henry Clay

- Legacy: The Democratic Party remains one of the oldest political parties in the U.S

Democratic Party Origins: Founded by Andrew Jackson's supporters in the 1820s, emphasizing democracy and states' rights

The Democratic Party, one of the oldest political parties in the United States, traces its roots directly to the supporters of Andrew Jackson in the 1820s. Jackson, a war hero and populist leader, galvanized a coalition of farmers, workers, and frontiersmen who felt marginalized by the elite-dominated political system of the time. His presidency, from 1829 to 1837, marked a seismic shift in American politics, as his followers formalized their movement into the Democratic Party. This party was not merely a vehicle for Jackson’s ambitions but a reflection of his core principles: expanding democracy and championing states’ rights against federal overreach.

Jackson’s supporters, often referred to as Jacksonians, were united by their belief in a more inclusive political system. They opposed the Whig Party, which they viewed as representing the interests of the wealthy and the establishment. The Democratic Party’s early platform emphasized the sovereignty of the common man, advocating for universal white male suffrage and the reduction of property qualifications for voting. This democratization of politics was revolutionary for its time, breaking the stranglehold of the aristocracy on governance. Jackson’s famous veto of the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States in 1832 exemplified his commitment to states’ rights and his distrust of centralized financial power, further solidifying the party’s ideological foundation.

The party’s emphasis on states’ rights was both a practical and philosophical stance. Jacksonians believed that power should reside as close to the people as possible, a principle that resonated deeply in an era of rapid westward expansion. This belief, however, also had its limitations and contradictions, particularly regarding the issue of slavery. While the party’s commitment to states’ rights allowed individual states to maintain their own institutions, it also enabled the perpetuation of slavery in the South, a moral and political fault line that would eventually lead to the Civil War. Despite this, the Democratic Party’s early focus on decentralization and local control remains a defining aspect of its origins.

To understand the Democratic Party’s formation, consider it as a response to the political and social upheavals of the early 19th century. Jackson’s supporters were not just backing a charismatic leader; they were endorsing a vision of America that prioritized the will of the majority and the autonomy of states. Practical steps taken by the party included organizing local and state-level political clubs, mobilizing voters through rallies and newspapers, and crafting policies that appealed to the diverse interests of their base. For instance, the party’s support for the Indian Removal Act of 1830, while controversial, aligned with the expansionist desires of many of its constituents.

In conclusion, the Democratic Party’s origins are deeply intertwined with Andrew Jackson’s legacy and the ideals of his supporters. By emphasizing democracy and states’ rights, the party carved out a distinct identity in American politics. While its early principles have evolved over time, the foundational commitment to grassroots governance and local autonomy remains a hallmark of its history. Studying this period offers valuable insights into how political movements are shaped by the aspirations and struggles of their time, and how those movements, in turn, shape the nation’s future.

Why Engaging in Politics Shapes Your Future and Society

You may want to see also

Jackson's Influence: His populist appeal and opposition to elites shaped the party's early identity

Andrew Jackson's political legacy is inextricably linked to the formation of the Democratic Party, a party that, in its early years, mirrored his own brand of populism and anti-elitism. His presidency, from 1829 to 1837, marked a significant shift in American politics, as he championed the rights of the common man against what he perceived as the entrenched power of the elite. This populist appeal became the cornerstone of the Democratic Party's identity, setting it apart from its rivals and shaping its course for decades to come.

The Rise of Jacksonian Democracy

Jackson's political ascent was fueled by his ability to connect with the masses. He portrayed himself as a man of the people, a self-made individual who understood the struggles of the average American. This image resonated with a population that was increasingly frustrated with the dominance of the political and economic elite. Jackson's opposition to the Second Bank of the United States, for instance, was framed as a battle against a corrupt institution that favored the wealthy at the expense of the common citizen. By vetoing the bank's recharter, he positioned himself as a defender of the people's interests, a move that solidified his populist credentials.

A Party Born from Populist Sentiment

The Democratic Party, as we know it today, emerged from the Democratic-Republican Party, largely due to Jackson's influence. His supporters, known as Jacksonians, advocated for a more inclusive political system, where power was not concentrated in the hands of a few. They believed in the expansion of suffrage, the protection of individual liberties, and the limitation of federal power, particularly in economic matters. This ideology, rooted in Jackson's own beliefs, became the foundation of the Democratic Party's platform, attracting a diverse range of supporters, from farmers and workers to small business owners.

Shaping Party Identity through Opposition

Jackson's opposition to elites was not merely a campaign strategy; it was a core principle that guided his actions and, consequently, the party's early policies. He vehemently opposed what he saw as the aristocracy's control over political and economic institutions. This included his resistance to the Whig Party, which he viewed as a representation of elite interests. By consistently challenging the status quo, Jackson and his followers created a distinct party identity, one that stood for the rights of the majority against the privileges of the few. This narrative of the common man versus the elite became a powerful tool in mobilizing support and defining the Democratic Party's mission.

A Lasting Impact on American Politics

The impact of Jackson's populism and anti-elitism can still be felt in modern American politics. The Democratic Party's early commitment to expanding democracy and challenging concentrated power has had a lasting influence on its policies and appeal. While the party has evolved over time, adapting to new social and economic realities, the core principles of Jacksonian democracy continue to shape its approach to governance. This includes a focus on economic equality, social justice, and the protection of individual rights, all of which can be traced back to Jackson's era. Understanding this historical context is crucial for comprehending the Democratic Party's enduring appeal and its position within the American political landscape.

Exploring Colombia's Diverse Political Landscape: Counting the Parties

You may want to see also

Key Principles: Focused on limited federal government, agrarian interests, and individual liberty

The Democratic Party, rooted in the legacy of Andrew Jackson, emerged with a distinct set of principles that prioritized limited federal government, agrarian interests, and individual liberty. These core values were not merely abstract ideals but practical responses to the socio-economic realities of early 19th-century America. Jacksonian Democrats championed a vision of government that would stay out of the way of the common man, particularly the small farmer, who was seen as the backbone of the nation. This philosophy was a direct counter to the Federalist and Whig emphasis on centralized authority and industrial development.

To understand the focus on limited federal government, consider the historical context of Jackson’s era. The early 1800s were marked by rapid westward expansion and a growing divide between agrarian and industrial interests. Jacksonians argued that a powerful federal government would favor the elite, such as bankers and industrialists, at the expense of ordinary citizens. For instance, Jackson’s veto of the Second Bank of the United States in 1832 was a bold assertion of this principle, as he viewed the bank as a tool of the wealthy that undermined economic equality. This action exemplified the party’s commitment to decentralizing power and ensuring that government remained responsive to the needs of the majority.

Agrarian interests were central to the Jacksonian platform, reflecting the economic dominance of farming in the early Republic. The party advocated for policies that supported small landowners, such as the distribution of public lands to settlers and the reduction of tariffs that disproportionately benefited industrialists. This focus was not merely nostalgic but pragmatic: agriculture was the primary source of livelihood for most Americans, and protecting it was seen as essential to preserving the nation’s independence and self-sufficiency. For example, the Homestead Act of 1862, though enacted later, embodied the spirit of Jacksonian agrarianism by granting public land to individuals willing to cultivate it.

Individual liberty, the third pillar of Jacksonian principles, was deeply intertwined with the party’s stance on limited government and agrarianism. Jacksonians believed that true freedom required economic independence, which was best achieved through land ownership and minimal government interference. This philosophy extended to political rights as well, as evidenced by the expansion of suffrage to include all white men, regardless of property ownership. However, this commitment to liberty was not without its contradictions, particularly in the context of Native American removal and the persistence of slavery, which undermined the ideals of equality and freedom for marginalized groups.

In practice, these principles shaped policies that had lasting impacts on American society. For instance, the emphasis on limited government influenced the development of states’ rights doctrines, which would later become contentious during the Civil War. The focus on agrarian interests laid the groundwork for populist movements in the late 19th century, which sought to protect farmers from the exploitative practices of railroads and corporations. Meanwhile, the ideal of individual liberty continues to resonate in modern debates about government overreach and personal autonomy.

To apply these principles today, consider their relevance in contemporary political discourse. Advocates for limited government might draw parallels between Jackson’s veto of the national bank and modern critiques of centralized financial institutions. Supporters of agrarian interests could push for policies that bolster small-scale farming and rural economies. And champions of individual liberty might use Jacksonian ideals to argue against regulatory overreach, while also acknowledging the need to address historical injustices that have limited freedom for certain groups. By studying the Jacksonian Democrats, we gain insights into how these principles can be adapted to address the challenges of our time.

How Political Parties Shape Election Outcomes and Voter Behavior

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.84 $26.95

Opposition to Whigs: Formed as a counter to the Whig Party, led by Henry Clay

The Democratic Party, rooted in the legacy of Andrew Jackson, emerged as a direct counterforce to the Whig Party, led by the formidable Henry Clay. This opposition was not merely a clash of personalities but a fundamental divergence in political philosophy. Jacksonians championed the common man, states’ rights, and limited federal intervention, while Whigs advocated for national economic development, internal improvements, and a stronger central government. This ideological rift shaped the early 19th-century political landscape, pitting agrarian interests against industrial aspirations.

To understand the Jacksonian opposition to the Whigs, consider their contrasting approaches to economic policy. Jacksonians distrusted centralized banking, exemplified by Jackson’s veto of the Second Bank of the United States, while Whigs, under Clay’s American System, promoted tariffs, infrastructure projects, and a national bank to foster economic growth. This divide was not just theoretical; it had tangible consequences, such as the Panic of 1837, which critics blamed on Jackson’s financial policies. For modern readers, this historical tension offers a lens to analyze contemporary debates over federal spending and economic regulation.

A practical takeaway from this opposition lies in its lessons for coalition-building. The Jacksonians’ success hinged on their ability to unite diverse groups—farmers, workers, and Southern planters—under a shared skepticism of elite-driven policies. Conversely, the Whigs struggled to bridge the gap between their urban, industrial base and rural constituencies. For political strategists today, this underscores the importance of crafting inclusive platforms that resonate across demographic lines, a principle as relevant now as it was in the 1830s.

Finally, the Jacksonian-Whig rivalry serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of polarization. While their opposition energized American politics, it also deepened regional and ideological divides that would later contribute to the Civil War. In an era of partisan gridlock, this history reminds us that while robust opposition is essential for democracy, it must be tempered by a commitment to common ground and national unity. Balancing principled opposition with pragmatic cooperation remains a challenge, but one that draws directly from the lessons of Jackson’s Democrats and Clay’s Whigs.

Lyndon B. Johnson's Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Legacy: The Democratic Party remains one of the oldest political parties in the U.S

The Democratic Party, born from the legacy of Andrew Jackson, stands as a testament to enduring political evolution. Founded in the 1820s, it emerged as a coalition of farmers, laborers, and Western settlers who rallied behind Jackson’s populist ideals. This party, initially known as the Democratic-Republican Party, rebranded itself as the Democratic Party in the 1830s, solidifying its identity as a champion of the "common man." Today, it remains one of the oldest political parties in the U.S., a rarity in a world where political movements often rise and fall with shifting tides. Its longevity is not merely a historical footnote but a reflection of its ability to adapt, reinvent, and resonate across generations.

To understand the Democratic Party’s legacy, consider its foundational principles. Jacksonian democracy emphasized states’ rights, limited federal government, and opposition to elite control. While the party’s modern platform has evolved significantly—now advocating for federal intervention in areas like healthcare and social welfare—its core identity as a party of the people persists. This adaptability is key to its survival. For instance, the party’s shift from supporting slavery in the 19th century to championing civil rights in the 20th century demonstrates its capacity to align with changing moral and societal norms. Practical tip: When analyzing political parties, trace their evolution against historical contexts to understand their resilience.

Comparatively, few political parties globally have matched the Democratic Party’s endurance. The U.K.’s Labour Party, founded in 1900, and Canada’s Liberal Party, established in 1867, are younger counterparts. The Democratic Party’s age is not just a number; it signifies a unique ability to navigate ideological shifts, demographic changes, and technological advancements. For example, the party’s embrace of digital campaigning in the 21st century allowed it to engage younger voters, ensuring its relevance in an increasingly tech-driven political landscape. Caution: While longevity is impressive, it can also lead to complacency. The party must continually address contemporary issues like climate change and economic inequality to avoid becoming a relic of the past.

Persuasively, the Democratic Party’s legacy offers lessons for modern political movements. Its survival underscores the importance of inclusivity and adaptability. By broadening its coalition—from rural farmers in the 1800s to urban professionals and minority groups today—the party has maintained its electoral viability. Takeaway: Political organizations must prioritize flexibility and responsiveness to endure. For new movements, this means avoiding rigid ideologies and instead fostering a dynamic platform that evolves with societal needs. Specific action: Engage with diverse communities through grassroots initiatives to build a broad, sustainable base.

Descriptively, the Democratic Party’s journey mirrors the complexities of American history. From the Age of Jackson to the New Deal era, from the Civil Rights Movement to the Obama presidency, it has been a central actor in shaping the nation’s trajectory. Its ability to reinvent itself—from a party of agrarian populism to one of urban progressivism—is a narrative of transformation. This legacy is not without contradictions, but it is precisely these tensions that make the party a living, breathing entity rather than a static institution. Practical tip: Study the Democratic Party’s historical pivots to understand how political organizations can navigate crises and capitalize on opportunities.

Power Struggles: Strategies of Nigerian Political Parties in Competition

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party is the political party formed from Andrew Jackson's political movement.

Andrew Jackson's presidency (1829–1837) solidified the Democratic Party by rallying supporters around his populist policies and expanding political participation to a broader segment of white male citizens.

The core principles included states' rights, limited federal government, opposition to centralized banking, and support for the common man against elite interests.

Jackson's supporters, known as Jacksonian Democrats, favored a more democratic political system and opposed the policies of the Whig Party, which supported a stronger federal government and economic modernization.

Andrew Jackson's leadership and policies defined the Democratic Party as a populist, anti-elitist movement, setting the tone for its future as a party representing the interests of the common people.