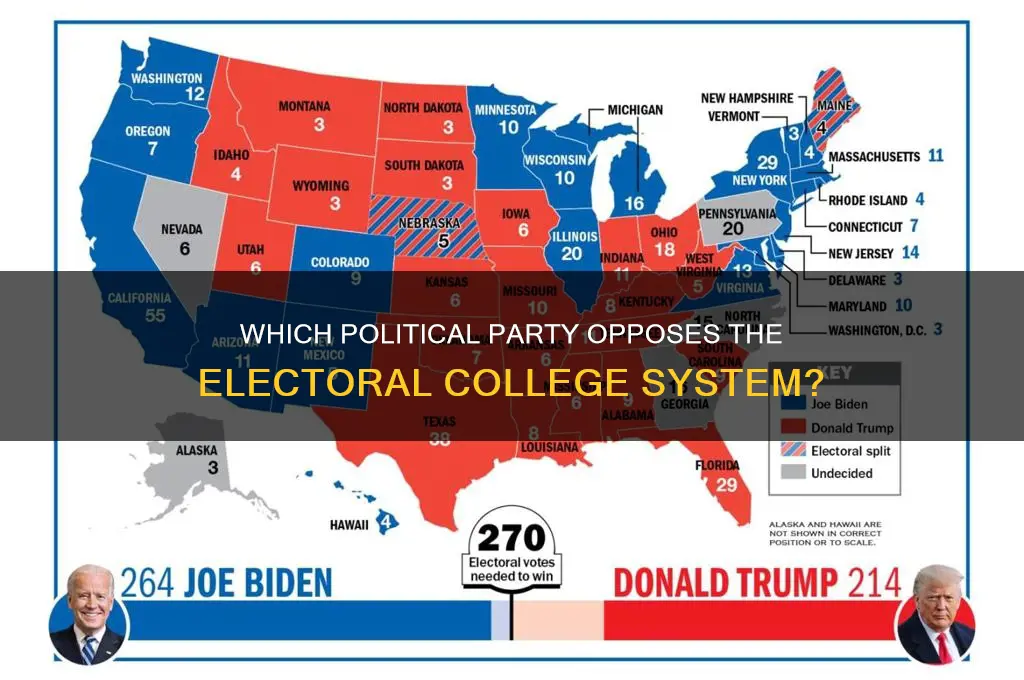

The Electoral College, a cornerstone of the U.S. presidential election system, has long been a subject of debate, with critics arguing it undermines the principle of one person, one vote. Among the political parties, the Democratic Party has been the most vocal opponent of the Electoral College, advocating for its abolition in favor of a national popular vote system. This stance is rooted in instances where Democratic candidates, such as Al Gore in 2000 and Hillary Clinton in 2016, won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College, leading to their defeat. Democrats argue that the current system disproportionately benefits smaller states and can distort the will of the majority, fueling their push for reform to ensure that the candidate who receives the most votes nationwide becomes president.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Democratic Party Stance: Many Democrats advocate for abolishing the Electoral College, favoring a popular vote system

- Progressive Movement: Progressives argue the Electoral College undermines democracy and disproportionately favors rural states

- Constitutional Amendments: Efforts to reform or eliminate the Electoral College through constitutional changes

- State-Level Reforms: Some states join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact to bypass the Electoral College

- Public Opinion Polls: Surveys show growing Democratic voter support for replacing the Electoral College with a direct vote

Democratic Party Stance: Many Democrats advocate for abolishing the Electoral College, favoring a popular vote system

The Democratic Party's stance on the Electoral College is clear: many of its members advocate for its abolition, favoring instead a system based on the popular vote. This position stems from the belief that the Electoral College distorts the principle of "one person, one vote," often allowing candidates to win the presidency without securing the majority of the popular vote. For instance, in the 2000 and 2016 elections, Democratic candidates Al Gore and Hillary Clinton, respectively, won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College, highlighting what many Democrats see as a fundamental flaw in the system.

Analytically, the Democratic push to abolish the Electoral College is rooted in both ideological and strategic considerations. Ideologically, Democrats argue that a popular vote system would ensure that every vote carries equal weight, regardless of the voter’s state of residence. Strategically, the current system disproportionately benefits smaller, often Republican-leaning states, where electoral votes are more numerous relative to population size. By shifting to a popular vote, Democrats believe they could better align electoral outcomes with the national will, particularly in an era of increasing urbanization and demographic shifts.

Persuasively, proponents of this stance often point to the Electoral College’s historical origins, which include compromises with slave-holding states that inflated the political power of the South. While this context is no longer directly relevant, critics argue that the system still perpetuates inequities by overrepresenting rural voters at the expense of urban and suburban ones. Democrats frame the abolition of the Electoral College as a step toward a more democratic and representative system, one that reflects the diversity and priorities of the entire nation rather than a handful of swing states.

Comparatively, the Democratic position contrasts sharply with that of the Republican Party, which has largely defended the Electoral College as a safeguard for smaller states and rural interests. Democrats counter that this defense often masks a reluctance to adapt to changing demographics and voting patterns. They argue that a popular vote system would incentivize candidates to campaign across the entire country, not just in battleground states, thereby broadening political engagement and reducing regional polarization.

Practically, abolishing the Electoral College would require a constitutional amendment, a daunting but not impossible task. Democrats have proposed alternative solutions, such as the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, where states agree to allocate their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. While this approach bypasses the need for a constitutional amendment, it has faced legal and political challenges. For individuals supporting this cause, practical steps include advocating for state legislatures to join the compact, engaging in grassroots campaigns, and pressuring elected officials to prioritize electoral reform. The takeaway is clear: the Democratic Party’s stance on the Electoral College is not just a policy position but a call for a more equitable and inclusive democracy.

Shepard Smith's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Preferences

You may want to see also

Progressive Movement: Progressives argue the Electoral College undermines democracy and disproportionately favors rural states

The Progressive Movement has long been at the forefront of challenging the Electoral College, arguing that it undermines the principles of democracy by distorting the weight of individual votes. Unlike a direct popular vote system, where every vote holds equal value, the Electoral College allocates votes by state, giving smaller, rural states disproportionate influence. For instance, Wyoming has three electoral votes for approximately 580,000 residents, while California’s 55 electoral votes represent over 39 million people. This disparity means a Wyoming voter has nearly four times the influence of a California voter in presidential elections. Progressives contend this imbalance contradicts the democratic ideal of "one person, one vote," favoring rural states at the expense of urban and suburban populations.

To illustrate the practical impact, consider the 2016 and 2020 elections, where candidates won the presidency despite losing the popular vote. Progressives argue these outcomes highlight the Electoral College’s tendency to prioritize geographic representation over the will of the majority. They emphasize that in a direct popular vote system, candidates would focus on winning the most votes nationwide, rather than targeting swing states like Pennsylvania or Florida. This shift, they claim, would encourage broader engagement and reduce the marginalization of voters in reliably "red" or "blue" states, whose votes currently hold less strategic value.

Progressives also critique the Electoral College for perpetuating a campaign strategy that neglects urban and densely populated areas. Since electoral votes are winner-take-all in most states, candidates often bypass states where they are unlikely to win, focusing instead on battleground states. This approach leaves millions of voters, particularly in cities, feeling ignored. For example, candidates rarely campaign in states like New York or Texas, assuming their electoral votes are already secured or out of reach. Progressives argue this undermines democratic participation by discouraging voter turnout in non-competitive states.

A key Progressive proposal to address these issues is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), an agreement among states to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. Currently, states representing 205 electoral votes have joined, though the compact only takes effect once states totaling 270 electoral votes sign on. This strategy bypasses the need for a constitutional amendment, offering a practical pathway to reform. Progressives view the NPVIC as a step toward ensuring that the candidate who wins the most votes nationwide becomes president, aligning the Electoral College with democratic principles.

In conclusion, the Progressive Movement’s critique of the Electoral College centers on its distortion of voter equality and its tendency to favor rural states. By advocating for reforms like the NPVIC, Progressives aim to create a system where every vote carries equal weight, regardless of geography. Their arguments challenge the status quo, urging a reevaluation of how the U.S. elects its president to better reflect the will of the majority. For those seeking to engage in this debate, understanding the Electoral College’s mechanics and its real-world consequences is essential to appreciating the Progressive perspective.

Manfred von Richthofen's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Constitutional Amendments: Efforts to reform or eliminate the Electoral College through constitutional changes

The Democratic Party has been the most vocal opponent of the Electoral College, particularly after the 2000 and 2016 presidential elections, where Democratic candidates won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College. This discrepancy has fueled calls for reform or abolition, with many Democrats arguing that the system undermines the principle of "one person, one vote." Efforts to address this issue have centered on constitutional amendments, a complex but necessary process given the Electoral College’s deep roots in the U.S. Constitution.

Steps to Amend the Constitution:

Amending the Constitution to reform or eliminate the Electoral College requires a two-step process. First, a proposed amendment must gain approval from two-thirds of both the House and the Senate, or through a constitutional convention called by two-thirds of state legislatures. Second, the amendment must be ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 out of 50). This high bar reflects the Founding Fathers’ intention to make constitutional changes deliberate and difficult, ensuring stability in the nation’s governing framework.

Historical Attempts and Their Outcomes:

Over 700 proposals to reform or abolish the Electoral College have been introduced in Congress since the nation’s founding. Notable examples include the 1969 Bayh-Celler Amendment, which sought to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote system. Despite passing the House Judiciary Committee, it stalled in the Senate amid concerns about rural states losing influence. More recently, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) has emerged as a state-level workaround, where states agree to allocate their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner. However, this approach bypasses the Constitution and remains controversial.

Cautions and Challenges:

Amending the Constitution to eliminate the Electoral College faces significant hurdles. Small and rural states, which benefit from the current system’s emphasis on state-level voting, are unlikely to support changes that diminish their influence. Additionally, the partisan divide on this issue complicates bipartisan cooperation. While Democrats largely favor reform, Republicans often argue that the Electoral College protects federalism and prevents large urban centers from dominating elections. This polarization underscores the difficulty of achieving the supermajorities required for constitutional change.

Practical Alternatives and Takeaways:

Given the challenges of amending the Constitution, reformers have explored alternative strategies. The NPVIC, though not a constitutional amendment, aims to achieve similar outcomes by coordinating state-level actions. As of 2023, 16 states and the District of Columbia have joined the compact, totaling 195 electoral votes—just 75 short of the 270 needed to activate it. While this approach sidesteps the need for a constitutional amendment, it raises legal and political questions about its legitimacy. For those advocating change, the lesson is clear: incremental, state-level efforts may offer a more feasible path than the daunting task of constitutional reform.

Kamala Harris' Political Affiliation: Unveiling Her Party Membership

You may want to see also

Explore related products

State-Level Reforms: Some states join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact to bypass the Electoral College

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) represents a strategic maneuver by states to neutralize the Electoral College’s influence without amending the Constitution. Under this agreement, member states pledge to award their electoral votes to the presidential candidate who wins the national popular vote, provided enough states join to reach the 270-vote threshold. Currently, 17 states and the District of Columbia, totaling 209 electoral votes, have signed on. This compact is a direct response to the Electoral College’s tendency to amplify the power of swing states while marginalizing voters in solidly red or blue states.

Consider the mechanics: once states representing 270 electoral votes join, the compact triggers, effectively ensuring the national popular vote winner secures the presidency. This reform bypasses the winner-take-all system in most states, where a candidate can lose the national vote but still win the Electoral College, as occurred in 2000 and 2016. For instance, California and New York, both NPVIC members, contribute 78 electoral votes combined, signaling a shift toward prioritizing every vote equally, regardless of geographic location.

Critics argue the compact could face legal challenges, particularly under the Constitution’s Compact Clause, which requires congressional approval for agreements between states that increase their political power. However, proponents counter that the NPVIC operates within the Electoral College framework, merely reallocating votes based on national, not state, results. This distinction is crucial, as it avoids direct confrontation with federal law while still achieving the goal of reflecting the will of the majority.

The NPVIC is inherently partisan in its appeal, with all member states currently leaning Democratic. This alignment reflects the Democratic Party’s frustration with the Electoral College’s recent outcomes, which have favored Republicans despite losing the popular vote. Yet, the compact’s design is nonpartisan in theory: it would apply uniformly regardless of which party wins the national vote. For example, if implemented in 2004, George W. Bush would still have won the presidency despite John Kerry’s narrow popular vote lead, as the compact simply mirrors the national result.

To join the compact, states must pass legislation and secure gubernatorial approval, a process that varies in difficulty depending on political control. Activists and lawmakers in non-member states often cite the compact as a practical alternative to the politically daunting task of constitutional amendment. While the NPVIC remains 61 electoral votes shy of activation, its growing membership underscores a tangible, state-driven effort to reform presidential elections without federal gridlock. This approach exemplifies how states can collaboratively address national issues, even when Congress remains stalemated.

Revolutionary Change: Do Political Parties Fuel or Hinder Progress?

You may want to see also

Public Opinion Polls: Surveys show growing Democratic voter support for replacing the Electoral College with a direct vote

Recent public opinion polls reveal a striking trend: Democratic voters are increasingly favoring the abolition of the Electoral College in favor of a direct national vote for presidential elections. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 74% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents support this change, up from 63% in 2016. This shift underscores a growing dissatisfaction with a system that has twice in the last two decades elevated candidates who lost the popular vote to the presidency. The data highlights a clear partisan divide, as Republican support for reform remains stagnant at around 25%, reflecting broader ideological differences about federalism and state representation.

This surge in Democratic support is not merely abstract; it’s rooted in specific grievances. Critics argue that the Electoral College distorts campaigns by focusing resources on a handful of swing states while ignoring larger, more diverse populations in safe states. For instance, in 2020, over 70% of campaign events were held in just six states. This imbalance fuels perceptions of disenfranchisement among voters in states like California and Texas, where outcomes are often predetermined. The polls suggest that Democratic voters increasingly view the Electoral College as an outdated mechanism that undermines the principle of "one person, one vote."

However, translating this public sentiment into policy change is fraught with challenges. Amending the Constitution requires a two-thirds majority in Congress and ratification by 38 states, a nearly insurmountable hurdle given Republican opposition. An alternative proposal, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, aims to bypass this by committing states to allocate their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner. While 17 states and D.C. have joined, representing 205 electoral votes, the compact remains 65 votes short of activation. This pragmatic approach reflects the difficulty of aligning public opinion with actionable reform.

Despite these obstacles, the polls serve as a barometer of evolving democratic ideals. They indicate that Democratic voters are not just reacting to recent election outcomes but are fundamentally rethinking the structure of American democracy. Advocates argue that a direct vote would incentivize candidates to appeal to a broader electorate, fostering more inclusive policies. Critics, however, warn of unintended consequences, such as increased polarization or the marginalization of rural voters. As the debate continues, these surveys provide a critical foundation for understanding the stakes and complexities of electoral reform.

Using Donor-Advised Funds for Political Parties: Legal or Off-Limits?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party is the most vocal opponent of the electoral college, with many of its members advocating for its abolition in favor of a national popular vote system.

The Democratic Party opposes the electoral college because it argues that the system can lead to outcomes where the winner of the popular vote does not become president, as seen in the 2000 and 2016 elections, which they view as undemocratic.

While the Republican Party generally supports the electoral college, some individual Republicans have proposed reforms, such as the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, though the party as a whole remains largely in favor of retaining the current system.