The Whigs were a prominent political party in the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries, emerging as a counterforce to the Tories, who later evolved into the Conservative Party. Rooted in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the Whigs championed constitutional monarchy, parliamentary sovereignty, and the protection of civil liberties, often aligning with the interests of the rising middle class and commercial elites. In the United States, the term Whig was adopted by a political party in the 1830s, known as the Whig Party, which advocated for modernization, economic development, and opposition to the Democratic Party’s dominance under Andrew Jackson. While the British Whigs eventually merged into the Liberal Party in the mid-19th century, their legacy influenced modern liberalism, and the American Whig Party, though short-lived, played a significant role in shaping early U.S. politics before dissolving in the 1850s.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Context | Originated in the United Kingdom in the 17th century; later influenced U.S. politics. |

| Ideology | Supported constitutional monarchy, parliamentary democracy, and free trade. |

| Economic Policies | Favored free markets, limited government intervention, and industrial growth. |

| Social Policies | Advocated for social reforms, including abolition of slavery and expansion of suffrage. |

| Political Alignment | Center-right to liberal, depending on the era and region. |

| Key Figures (UK) | Earl Grey, Robert Peel, William Pitt the Younger. |

| Key Figures (U.S.) | Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln (early career). |

| Modern Influence | Defunct as a formal party but influenced modern liberalism and conservatism. |

| Opposition | Opposed the Tory Party in the UK and the Democratic-Republican Party in the U.S. |

| Legacy | Laid the groundwork for modern political parties and democratic principles. |

Explore related products

$48.99 $55

What You'll Learn

- Whig Party Origins: Founded in 1830s U.S., opposing Andrew Jackson's policies, emphasizing economic modernization

- Whig Principles: Supported protective tariffs, national banking, and internal improvements for economic growth

- Notable Whigs: Included presidents William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Abraham Lincoln (early)

- Whig Decline: Collapsed in 1850s due to internal divisions over slavery and rise of Republicans

- Modern Whigs: Unrelated to historical Whigs, a minor U.S. party formed in 2007

Whig Party Origins: Founded in 1830s U.S., opposing Andrew Jackson's policies, emphasizing economic modernization

The Whig Party emerged in the 1830s as a direct response to the policies of President Andrew Jackson, whose Democratic Party dominated American politics at the time. Jackson’s aggressive approach to executive power, his opposition to centralized banking, and his controversial policies toward Native Americans galvanized a coalition of diverse opponents. These critics, united by their shared disdain for Jacksonian democracy, coalesced into the Whig Party, named after the British Whigs who had opposed monarchical tyranny. This new American party was not merely a reactionary force but a forward-looking movement that championed economic modernization, internal improvements, and a stronger federal role in fostering national growth.

To understand the Whigs’ emphasis on economic modernization, consider their advocacy for infrastructure projects like roads, canals, and railroads. Unlike Jackson, who vetoed bills for such initiatives, the Whigs believed federal investment in these areas was essential for connecting the vast American landscape and stimulating commerce. For instance, the Whigs supported the American System, a program championed by Henry Clay, which included protective tariffs, a national bank, and federally funded internal improvements. This vision contrasted sharply with Jackson’s laissez-faire approach, which prioritized individual states’ rights over national development. By framing their agenda as a pathway to prosperity, the Whigs appealed to entrepreneurs, industrialists, and urban workers who saw economic modernization as key to America’s future.

The Whigs’ opposition to Jackson was not just about policy but also about principles of governance. They criticized Jackson’s use of executive power, particularly his defiance of the Supreme Court in the Cherokee removal crisis and his dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States. The Whigs argued for a more balanced government where Congress played a stronger role, a stance that resonated with those wary of presidential overreach. This ideological clash laid the groundwork for the Whigs’ rise as a viable alternative to the Democrats, though their success was often hindered by internal divisions and the charismatic appeal of Jackson and his successor, Martin Van Buren.

A practical takeaway from the Whigs’ origins is their ability to unite disparate groups under a common cause. The party brought together National Republicans, anti-Masons, and disaffected Democrats, demonstrating the power of coalition-building in politics. However, their reliance on opposition to Jackson rather than a cohesive platform ultimately limited their longevity. By the 1850s, the Whig Party dissolved, largely due to its inability to address the growing issue of slavery. Yet, their legacy endures in their contributions to American political thought, particularly their emphasis on economic modernization and federal activism, which influenced later Republican policies.

In retrospect, the Whig Party’s origins highlight the complexities of early 19th-century American politics. Their formation was a testament to the era’s ideological battles, where questions of federal power, economic policy, and national identity were fiercely contested. While the Whigs may have faded into history, their ideas continue to shape discussions about the role of government in fostering economic growth and national unity. For modern readers, studying the Whigs offers valuable insights into how political movements can emerge from opposition and how their legacies can outlast their existence.

Which Political Party Advocates for Ending DACA? A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Whig Principles: Supported protective tariffs, national banking, and internal improvements for economic growth

The Whig Party, a dominant force in American politics during the mid-19th century, championed a set of economic principles designed to foster national growth and development. Central to their agenda were protective tariffs, national banking, and internal improvements. These policies were not mere theoretical constructs but practical tools aimed at building a robust, industrialized nation. Protective tariffs, for instance, shielded American industries from foreign competition, allowing domestic manufacturers to grow without being undercut by cheaper imports. This strategy was particularly crucial in the early stages of industrialization when American factories were still finding their footing.

Consider the impact of national banking, another cornerstone of Whig policy. The Whigs advocated for a centralized banking system to stabilize the economy and provide a uniform currency. This was in stark contrast to the state-by-state banking systems that often led to financial chaos and inconsistent currency values. The establishment of a national bank under Whig President John Quincy Adams, though short-lived, laid the groundwork for future financial stability. It ensured that businesses had access to reliable credit and that the government could manage economic fluctuations more effectively. For entrepreneurs and investors, this meant a more predictable environment in which to operate and expand.

Internal improvements, the third pillar of Whig economic policy, focused on infrastructure projects like roads, canals, and railroads. These were not just public works projects but vital arteries for commerce and communication. Take the example of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, which connected the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, drastically reducing transportation costs and opening up new markets. Whigs believed that such projects were essential for connecting the vast American landscape and fostering economic interdependence among states. By investing in infrastructure, they aimed to create a network that would facilitate trade, reduce regional disparities, and accelerate industrialization.

However, these policies were not without controversy. Protective tariffs, while beneficial to manufacturers, often raised prices for consumers, particularly in the agricultural South, where imported goods were more affordable. National banking faced resistance from states’ rights advocates who viewed it as an overreach of federal power. Internal improvements, too, were criticized for their high costs and the potential for corruption in their implementation. Yet, the Whigs argued that these short-term challenges were necessary investments in the nation’s long-term prosperity. Their vision was one of a unified, industrialized America, where economic growth was not just a goal but a shared national endeavor.

In practice, the Whig principles of protective tariffs, national banking, and internal improvements offer a blueprint for economic development that remains relevant today. For modern policymakers, the Whig model underscores the importance of strategic government intervention in fostering key industries, ensuring financial stability, and investing in infrastructure. While the specifics of these policies would need to be adapted to the 21st-century economy, the underlying principles—protection, stability, and connectivity—continue to resonate. Whether applied to emerging technologies or global trade, the Whig approach reminds us that economic growth often requires bold, forward-thinking policies.

Harrison Ford's Political Party: Uncovering the Actor's Affiliation

You may want to see also

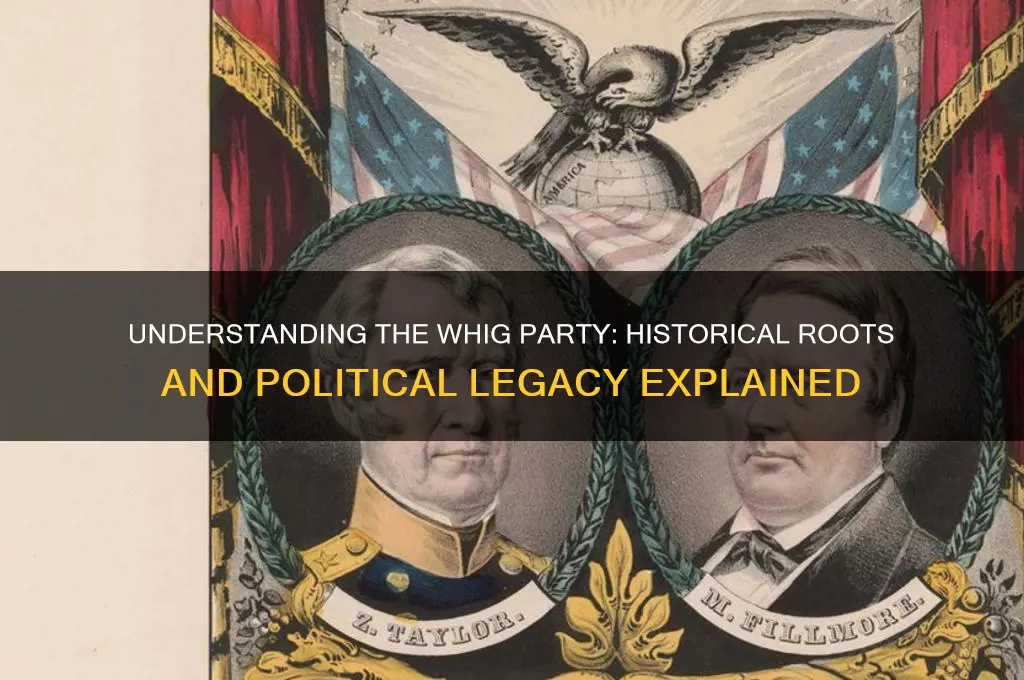

Notable Whigs: Included presidents William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Abraham Lincoln (early)

The Whig Party, though short-lived, left an indelible mark on American history, particularly through its presidential figures. Among the most notable Whigs were William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and an early Abraham Lincoln. Each of these leaders embodied the party’s core principles of modernization, economic development, and national unity, though their legacies are as varied as their presidencies.

William Henry Harrison, the ninth president, is often remembered for his brevity in office—serving just 31 days before succumbing to illness. However, his political career was marked by a strong Whig identity. As a military hero, Harrison’s campaign leaned heavily on his image as a man of action, aligning with the Whig emphasis on internal improvements and national growth. His presidency, though cut short, symbolized the party’s rise as a counter to Jacksonian democracy. A practical takeaway from Harrison’s tenure is the importance of aligning personal narratives with party platforms, a strategy still relevant in modern political campaigns.

Zachary Taylor, the 12th president, brought a unique perspective to the Whig Party as a career military officer with limited political experience. His election in 1848 reflected the Whigs’ ability to appeal to voters beyond their traditional base. Taylor’s presidency was defined by his reluctance to embrace the party’s legislative agenda, particularly on issues like tariffs and infrastructure. This tension highlights a cautionary lesson: while a candidate’s popularity can win elections, ideological misalignment can hinder governance. For instance, Taylor’s opposition to the Compromise of 1850 alienated Whig leaders, underscoring the need for unity between a president and their party.

Abraham Lincoln’s early political career as a Whig is often overshadowed by his later Republican presidency, but it was during this period that he honed his political skills and ideological framework. Lincoln’s Whig roots shaped his commitment to economic modernization, including support for railroads, banking, and education. His debates in the 1830s and 1840s laid the groundwork for his later leadership, demonstrating how early political affiliations can influence long-term legacies. A comparative analysis reveals that while Lincoln’s Whig years were formative, his eventual shift to the Republican Party allowed him to address the moral and political crises of the Civil War era more effectively.

In examining these three figures, a clear pattern emerges: the Whig Party served as a crucible for leadership, shaping presidents who, despite their differences, shared a vision of national progress. Harrison’s symbolism, Taylor’s independence, and Lincoln’s evolution illustrate the party’s complexity and its enduring impact on American politics. For those studying political history or seeking to understand the roots of modern parties, the Whigs offer a rich case study in how ideology, personality, and circumstance intersect to shape leadership.

Which Political Party Championed State Prohibition Laws in America?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Whig Decline: Collapsed in 1850s due to internal divisions over slavery and rise of Republicans

The Whig Party, once a dominant force in American politics, met its demise in the 1850s, a collapse fueled by internal divisions over slavery and the rise of the Republican Party. Founded in the 1830s as a coalition opposed to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, the Whigs championed economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong federal government. However, their inability to forge a unified stance on slavery, the most contentious issue of the era, sowed the seeds of their downfall. While Northern Whigs increasingly aligned with abolitionist sentiments, Southern Whigs clung to pro-slavery positions, creating an irreconcilable rift within the party.

Consider the 1850 Compromise, a legislative package aimed at resolving sectional tensions over slavery. Northern Whigs, such as William Seward, viewed it as a moral concession to the South, while Southern Whigs, like John J. Crittenden, saw it as a necessary compromise to preserve the Union. This internal discord eroded party unity, as Whigs failed to present a coherent platform on the defining issue of the day. The party’s inability to adapt to the shifting political landscape left it vulnerable to newer, more ideologically cohesive movements.

The rise of the Republican Party in the mid-1850s further accelerated the Whigs’ decline. Formed primarily by former Northern Whigs, Anti-Slavery Democrats, and Free Soilers, the Republicans offered a clear, uncompromising stance against the expansion of slavery. Their platform resonated with Northern voters, who were increasingly disillusioned with the Whigs’ equivocation. By 1856, the Republicans had emerged as the primary opposition to the Democrats, effectively supplanting the Whigs as the dominant party in the North. The Whigs’ last presidential candidate, Millard Fillmore, ran a futile campaign in 1856, capturing just 21.5% of the popular vote, a stark indicator of the party’s collapse.

To understand the Whigs’ downfall, examine their structural weaknesses. Unlike the Democrats, who maintained a broad coalition through appeals to states’ rights and popular sovereignty, the Whigs lacked a unifying ideology beyond opposition to Jacksonianism. Their reliance on economic issues, such as tariffs and infrastructure, became secondary to the moral and sectional crisis over slavery. Practical tip: Political parties must prioritize ideological clarity and adaptability to survive in times of national upheaval. The Whigs’ failure to do so serves as a cautionary tale for modern parties navigating divisive issues.

In conclusion, the Whig Party’s collapse in the 1850s was not merely a result of external pressures but a self-inflicted wound. Their inability to address internal divisions over slavery, coupled with the rise of a more cohesive Republican Party, rendered them obsolete. This historical example underscores the importance of unity and ideological coherence in sustaining political movements, particularly during periods of intense national polarization.

Key Functions of Political Parties: Roles and Responsibilities Explained

You may want to see also

Modern Whigs: Unrelated to historical Whigs, a minor U.S. party formed in 2007

The Modern Whig Party, established in 2007, bears no direct ideological or historical connection to the 19th-century American Whig Party. Instead, it emerged as a response to contemporary political polarization, positioning itself as a pragmatic, centrist alternative. Unlike its historical namesake, which focused on industrialization and national development, the Modern Whigs prioritize fiscal responsibility, limited government, and evidence-based policy-making. This party appeals to voters disillusioned with the binary extremes of the two-party system, offering a platform that transcends traditional left-right divides.

To understand the Modern Whigs, consider their core principles: pragmatism over ideology, fiscal conservatism paired with social tolerance, and a commitment to bipartisan solutions. For instance, they advocate for balanced budgets and reduced national debt while supporting individual freedoms and environmental sustainability. This blend of policies distinguishes them from both major parties, though their minor-party status limits their electoral impact. Practical engagement with the Modern Whigs might involve attending local chapter meetings or reviewing their policy briefs to assess alignment with personal values.

A comparative analysis reveals the Modern Whigs’ unique position in the U.S. political landscape. Unlike the Libertarian Party, which emphasizes absolute individual liberty, or the Green Party, which focuses on environmentalism, the Modern Whigs aim for a middle ground. They are not a protest party but a constructive one, seeking to bridge partisan gaps. However, their lack of historical roots and limited resources pose challenges to gaining traction. For those considering supporting them, it’s essential to weigh their ideals against their practical ability to influence policy.

Persuasively, the Modern Whigs offer a refreshing perspective in an era of gridlock and hyper-partisanship. Their focus on results over rhetoric resonates with voters seeking functional governance. Yet, their success hinges on overcoming structural barriers, such as ballot access and media visibility. Engaging with this party requires patience and a long-term view, as minor parties often face an uphill battle in a system dominated by Democrats and Republicans. For the politically disenchanted, the Modern Whigs present a viable, if modest, alternative worth exploring.

Understanding the Role and Impact of Independent Parties in Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Whig Party was a major political party in the United States during the mid-19th century, active from the 1830s to the 1850s.

No, the Whig Party dissolved in the 1850s, primarily due to internal divisions over slavery and the rise of the Republican Party.

The Whigs advocated for a strong federal government, economic modernization, infrastructure development, and opposed the expansion of slavery.

Whigs supported federal intervention in the economy, such as tariffs and internal improvements, while Democrats favored states' rights, limited government, and agrarian interests.

Prominent Whigs included presidents William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore, as well as leaders like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.

![By Michael F. Holt - The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics (1999-07-02) [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51TQpKNRjoL._AC_UY218_.jpg)