The 1860 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as the Republican Party emerged as a dominant force, gaining significant support and ultimately securing the presidency with the election of Abraham Lincoln. Amidst deep national divisions over slavery and states' rights, the Republicans capitalized on their platform opposing the expansion of slavery into new territories, which resonated strongly in the North. The party's rise was further bolstered by the fragmentation of the Democratic Party, which split into Northern and Southern factions, and the decline of the Whig Party, leaving a political vacuum that the Republicans effectively filled. Lincoln's victory not only signaled a shift in political power but also set the stage for the Civil War, as Southern states viewed his election as a direct threat to their way of life.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Republican Party |

| Year of Significant Support Gain | 1860 |

| Key Figure | Abraham Lincoln |

| Primary Platform | Opposition to the expansion of slavery into new territories |

| Election Outcome | Abraham Lincoln elected as the 16th President of the United States |

| Impact on Slavery | Set the stage for the eventual abolition of slavery with the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and the 13th Amendment (1865) |

| Regional Support | Strong support in the Northern states; minimal support in the Southern states |

| Economic Policies | Supported tariffs, banking reforms, and infrastructure development |

| Long-Term Significance | Established the Republican Party as a dominant force in American politics for decades |

| Opposition | Faced strong opposition from the Democratic Party and Southern secessionists |

| Historical Context | Gained support amid rising tensions over slavery, leading to the American Civil War (1861–1865) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Republican Party's Rise

The 1860 U.S. presidential election marked a seismic shift in American politics, with the Republican Party emerging as a dominant force. Founded just six years prior in 1854, the Republicans capitalized on the growing sectional divide over slavery, particularly in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise. By framing their platform around the principle of "free soil, free labor, free men," the party attracted a broad coalition of Northern voters who opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. This ideological clarity and strategic positioning set the stage for their rapid ascent.

One of the key factors in the Republican Party's rise was its ability to unify disparate groups under a common cause. Northern Whigs, anti-slavery Democrats, and members of the short-lived Free Soil Party found a home within the Republican ranks. The party's first presidential nominee, John C. Frémont, in 1856, helped solidify its national presence, even though he lost the election. By 1860, the Republicans had honed their message, emphasizing economic opportunity and moral opposition to slavery, which resonated deeply with Northern voters. This coalition-building was crucial in a political landscape fractured by regional and ideological differences.

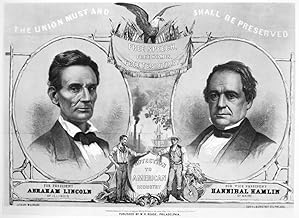

The 1860 election itself was a testament to the Republican Party's strategic brilliance. Abraham Lincoln, a relatively unknown figure on the national stage, secured the nomination by positioning himself as a moderate voice within the party. His election, with 180 electoral votes despite not appearing on the ballot in most Southern states, demonstrated the party's strength in the North. Lincoln's victory was not just a political triumph but a reflection of the North's demographic and economic power, which the Republicans had successfully harnessed. The South's reaction, including secession, further underscored the party's role in reshaping the nation's political and territorial boundaries.

To understand the Republican Party's rise, consider it as a case study in political mobilization. The party's leaders effectively used newspapers, rallies, and grassroots organizing to spread their message. They also leveraged the growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North, framing the issue not just as a moral imperative but as a threat to Northern economic interests. For instance, the "Gag Rule" debates in Congress and the Dred Scott decision fueled public outrage, which the Republicans channeled into electoral support. This combination of moral appeal and practical argumentation proved irresistible to many voters.

In practical terms, the Republican Party's rise offers lessons for modern political movements. First, clarity of purpose is essential; the Republicans' unwavering stance against slavery gave them a distinct identity. Second, coalition-building is critical; by uniting diverse groups, the party created a powerful electoral bloc. Finally, effective messaging matters; the Republicans framed their agenda in ways that resonated with both moral and economic concerns. For anyone studying political strategy, the Republican Party's ascent in 1860 is a masterclass in how to transform ideological conviction into political power.

Jair Bolsonaro's Political Party: Unraveling His Affiliation and Ideology

You may want to see also

Abraham Lincoln's Nomination

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Amidst this turmoil, the Republican Party emerged as a significant force, capturing the presidency with the nomination of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln's rise was not merely a personal triumph but a strategic victory for a party that had only recently been established. His nomination exemplified the Republicans' ability to coalesce diverse factions around a platform that opposed the expansion of slavery, appealing to both moderate and radical elements within the North.

To understand Lincoln's nomination, consider the Republican Party's strategic positioning. Founded in 1854, the party quickly gained traction by uniting former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats. By 1860, it had become the dominant political force in the North, leveraging widespread discontent with the Democratic Party's pro-slavery stance. Lincoln's nomination at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago was a masterstroke of political maneuvering. His moderate views on slavery—opposing its expansion but not its immediate abolition—made him an acceptable candidate to both the party's radical and conservative wings. This balance was crucial in securing his nomination over more polarizing figures like William H. Seward.

The nomination process itself was a study in political pragmatism. Lincoln's campaign team, led by figures like David Davis, worked tirelessly to build support across the North. They emphasized Lincoln's humble origins, legal expertise, and unwavering commitment to the Union, framing him as a unifying figure in a deeply divided nation. His famous "House Divided" speech, though delivered in 1858, resonated with voters who feared the nation's collapse. By the time of the convention, Lincoln had amassed enough delegates to secure the nomination on the third ballot, outmaneuvering better-known rivals.

Lincoln's nomination had immediate and far-reaching consequences. It solidified the Republican Party's position as the primary opposition to slavery's expansion, galvanizing Northern voters. However, it also deepened Southern fears of federal overreach, prompting several Southern states to secede even before Lincoln took office. This underscores the dual nature of his nomination: a triumph for the Republican Party and a catalyst for the nation's descent into civil war. Lincoln's ability to navigate these complexities during his presidency would ultimately define his legacy.

In retrospect, Abraham Lincoln's nomination was a turning point in American politics. It demonstrated the Republican Party's skill in harnessing anti-slavery sentiment while maintaining broad appeal. For modern observers, it offers a lesson in the power of strategic positioning and coalition-building in politics. By focusing on unity and principled opposition to slavery, Lincoln and the Republicans not only won the election but also set the stage for the eventual abolition of slavery. This historical moment remains a testament to the impact of leadership and party strategy in shaping a nation's future.

Political Parties Clash: Diverse Views on Internet Privacy Rights

You may want to see also

Anti-Slavery Platform Appeal

The 1860 U.S. presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery. Amidst this turmoil, the Republican Party emerged as a major force, largely due to its Anti-Slavery Platform Appeal. This platform, centered on halting the expansion of slavery into new territories, resonated with a growing segment of the electorate, particularly in the North. By framing the issue as a moral imperative and an economic safeguard for free labor, the Republicans successfully mobilized voters who sought to preserve the Union while containing the institution of slavery.

To understand the appeal, consider its strategic focus on territorial expansion. The Republican Party argued that preventing slavery from spreading into new states would not only protect the rights of free laborers but also ensure that the nation’s future economic growth was built on the principles of liberty and equality. This message was particularly effective among Northern farmers, artisans, and emerging industrial workers, who feared competition from slave-based economies. For instance, the party’s stance on the Homestead Act, which promised free land to settlers, was intertwined with its anti-slavery rhetoric, creating a compelling vision of opportunity for working-class Americans.

A key element of the Anti-Slavery Platform Appeal was its moral clarity. The Republicans framed slavery as a moral evil incompatible with the nation’s founding principles. This approach tapped into the growing influence of religious and reform movements, such as the abolitionists and the Second Great Awakening, which emphasized personal responsibility and social justice. By aligning their platform with these values, the Republicans positioned themselves as the party of conscience, attracting voters who saw the fight against slavery as a sacred duty. Practical tips for activists at the time included distributing pamphlets, organizing local meetings, and leveraging church networks to spread the message.

Comparatively, the Democratic Party’s internal divisions over slavery weakened its appeal, particularly after the fractious 1860 convention. While the Democrats nominated two candidates—Stephen A. Douglas in the North and John C. Breckinridge in the South—their inability to present a unified stance on slavery left a void that the Republicans filled. The Anti-Slavery Platform Appeal capitalized on this disarray, offering a clear and consistent alternative that resonated with voters seeking stability and moral leadership. This contrast highlights the importance of unity and purpose in political messaging, a lesson still relevant today.

Finally, the success of the Anti-Slavery Platform Appeal underscores the power of targeted messaging. The Republicans tailored their arguments to specific demographics, addressing the economic anxieties of Northern workers, the moral convictions of religious voters, and the patriotic concerns of those worried about the Union’s future. This multi-faceted approach not only secured Abraham Lincoln’s victory in 1860 but also laid the groundwork for the eventual abolition of slavery. For modern political campaigns, the takeaway is clear: effective platforms must combine moral principles with practical solutions, addressing both the hearts and minds of voters.

Are Political Parties Unconstitutional? Exploring the Legal Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Northern Voter Shift

The 1860 presidential election marked a seismic shift in American politics, with the Republican Party emerging as a major force. This transformation was particularly evident in the North, where voters increasingly aligned with the party's platform. A key factor in this Northern voter shift was the issue of slavery, which the Republicans staunchly opposed, in contrast to the more ambivalent stance of the Democratic Party. As tensions over slavery escalated, Northern voters began to see the Republicans as the party best equipped to address their concerns and protect their economic interests.

To understand the mechanics of this shift, consider the demographic and economic landscape of the North. The region was characterized by a rapidly growing industrial economy, which relied heavily on free labor and was increasingly at odds with the slave-based economy of the South. The Republican Party's platform, which emphasized tariffs, internal improvements, and the exclusion of slavery from the territories, resonated with Northern voters who saw these policies as essential to their economic prosperity. For instance, the 1860 Republican platform's call for a protective tariff to shield Northern manufacturers from foreign competition was a direct appeal to the region's industrialists and workers.

A comparative analysis of voting patterns in key Northern states illustrates the extent of this shift. In states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, the Republican Party's support surged between the 1856 and 1860 elections. In Pennsylvania, for example, the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, secured 56% of the vote in 1860, up from 43% for the party's candidate in 1856. This increase was not merely a reflection of anti-Democratic sentiment but a deliberate choice by voters to align with a party that championed their economic and moral values. The shift was particularly pronounced among urban voters, who were more directly impacted by the economic policies advocated by the Republicans.

Persuasive arguments played a crucial role in this realignment. Republican leaders effectively framed the election as a choice between two distinct visions for the country: one that upheld the principles of free labor and economic opportunity, and another that sought to perpetuate the institution of slavery. Speeches, pamphlets, and newspaper editorials highlighted the moral and economic dangers of allowing slavery to expand, resonating with Northern voters who increasingly viewed slavery as a threat to their way of life. This narrative was particularly compelling in the context of the Dred Scott decision and the ongoing debates over the admission of new slave states, which many Northerners saw as a direct assault on their values.

Finally, the Northern voter shift of 1860 had profound and lasting implications for American politics. It solidified the Republican Party's position as the dominant political force in the North and set the stage for the Civil War by polarizing the country along regional and ideological lines. For modern observers, this historical episode offers valuable insights into the dynamics of political realignment. It underscores the importance of aligning party platforms with the economic and moral concerns of key voter demographics and the power of persuasive messaging in shaping electoral outcomes. By studying this shift, we can better understand how issues like economic policy and moral values can drive voter behavior and transform the political landscape.

Justin Mirgeaux's Political Party Affiliation in St. Johns County

You may want to see also

Democratic Party Split

The 1860 U.S. presidential election was a seismic event, reshaping the political landscape and setting the stage for the Civil War. Amidst this turmoil, the Democratic Party, once a dominant force, fractured along regional lines, with the issue of slavery acting as the primary wedge. This split was not merely a disagreement over policy but a fundamental divergence in values and visions for the nation’s future. The Southern Democrats, staunch defenders of states’ rights and slavery, clashed with their Northern counterparts, who sought to limit the expansion of slavery and preserve the Union. This internal conflict not only weakened the party but also paved the way for the rise of the Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, who ultimately won the election.

To understand the mechanics of this split, consider the Democratic National Convention of 1860. Held in Charleston, South Carolina, and later reconvened in Baltimore, Maryland, the convention became a battleground for ideological warfare. Southern delegates demanded a platform explicitly endorsing the protection of slavery in the territories, while Northern delegates resisted, fearing such a stance would alienate voters in the North. The impasse led to a dramatic walkout by Southern delegates, who later nominated their own candidate, John C. Breckinridge, under the banner of the Southern Democratic Party. Meanwhile, Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas, a moderate who supported popular sovereignty on the slavery question. This division ensured that the Democratic vote would be split, handing the election to Lincoln, who had not even appeared on the ballot in most Southern states.

The consequences of this split were profound and far-reaching. By fragmenting the Democratic Party, the election of 1860 exposed the irreconcilable differences between North and South, accelerating the nation’s slide into civil war. For modern observers, this serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of allowing ideological purity to trump unity. In practical terms, political parties today must navigate internal divisions carefully, balancing diverse viewpoints without alienating core constituencies. For instance, holding inclusive caucuses, fostering open dialogue, and crafting platforms that address regional concerns can help prevent catastrophic splits.

A comparative analysis of the 1860 Democratic split and contemporary political divisions reveals striking parallels. Just as slavery was the litmus test of the 19th century, issues like immigration, climate change, and economic inequality now polarize parties. However, the 1860 Democrats lacked the mechanisms for compromise that modern parties often employ, such as superdelegates or brokered conventions. Today’s parties can learn from this historical example by prioritizing coalition-building over ideological rigidity. For activists and party leaders, this means investing time in grassroots engagement, understanding regional priorities, and crafting policies that appeal to a broad spectrum of voters.

Finally, the Democratic Party split of 1860 underscores the fragility of political institutions when faced with existential questions. It reminds us that parties are not monolithic entities but coalitions of interests, held together by shared goals and compromises. For those studying political history or engaged in activism, the lesson is clear: unity is not achieved by suppressing dissent but by finding common ground. Practical steps include conducting regular surveys to gauge voter sentiment, organizing cross-regional forums, and developing leadership training programs that emphasize collaboration. By heeding these lessons, modern parties can avoid the pitfalls of division and build a more resilient political landscape.

Randall Woodfin's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party gained significant support in the 1860 U.S. presidential election, leading to the victory of Abraham Lincoln.

The Republican Party gained support in 1860 primarily due to its stance against the expansion of slavery into new territories, which resonated strongly in the North.

The Republican Party's victory in 1860, with Abraham Lincoln as its candidate, deepened sectional divisions and was a major catalyst for the secession of Southern states, leading to the American Civil War.

![Republican "Campaign" Text-Book, for the Year 1860 1860 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)