The 1852 U.S. presidential election marked a significant turning point in American political history, as it effectively signaled the end of the Whig Party as a major national force. Despite nominating General Winfield Scott, a respected military leader, the Whigs were unable to overcome deep internal divisions over slavery and economic policies, which had been exacerbated by the Compromise of 1850. The party's inability to unite its northern and southern factions, coupled with the rise of the Democratic Party and the emergence of the nativist Know-Nothing movement, led to a crushing defeat for Scott, who won only four states. This electoral failure, combined with the party's ideological fragmentation, rendered the Whigs incapable of sustaining their political relevance, ultimately leading to the party's dissolution and the realignment of American politics along new sectional and ideological lines.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Whig Party |

| Year Ended | 1856 (effectively dissolved after the 1852 election) |

| Reason for Decline | Internal divisions over slavery and inability to unite on key issues |

| Key Figures | Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John Quincy Adams |

| Primary Ideology | National unity, economic modernization, opposition to extremism |

| Major Achievements | Supported industrialization, infrastructure development, and the Union |

| Last Presidential Candidate | Winfield Scott (1852) |

| Successor Parties | Members joined the Republican Party, American Party, and Constitutional Union Party |

| Historical Significance | Played a crucial role in pre-Civil War American politics |

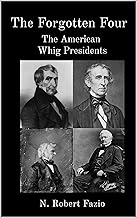

Explore related products

$48.99 $55

What You'll Learn

- Whig Party's Decline: Internal divisions over slavery and lack of strong leadership led to its downfall

- Election of 1852: Franklin Pierce's victory as a Democrat signaled the Whigs' inability to compete

- Sectional Tensions: North-South conflicts over slavery eroded Whig unity and public support

- Rise of Republicans: The new Republican Party absorbed former Whigs opposed to slavery expansion

- Legacy of Compromise: Failed compromises like the Compromise of 1850 weakened Whig political relevance

Whig Party's Decline: Internal divisions over slavery and lack of strong leadership led to its downfall

The 1852 presidential election marked a turning point in American political history, as it signaled the beginning of the end for the Whig Party. Founded in the 1830s in opposition to President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party, the Whigs had initially gained traction by advocating for a strong federal government, internal improvements, and a national bank. However, by the early 1850s, the party was plagued by internal divisions, particularly over the issue of slavery, which ultimately led to its downfall. The Whigs’ inability to present a unified front on this contentious matter, coupled with a lack of strong leadership, rendered the party increasingly irrelevant in a nation hurtling toward sectional conflict.

Consider the Whigs’ 1852 presidential nominee, General Winfield Scott. Despite his impressive military credentials, Scott’s campaign was hamstrung by the party’s inability to agree on a clear stance regarding the expansion of slavery into new territories. While Northern Whigs leaned toward restricting slavery, their Southern counterparts vehemently opposed any such measures, fearing economic and political marginalization. This ideological rift was exacerbated by the Compromise of 1850, which temporarily papered over the slavery issue but left the Whigs deeply fractured. Scott’s defeat to Democrat Franklin Pierce was not merely a loss in an election but a symptom of the party’s terminal illness: irreconcilable differences over slavery that no amount of political maneuvering could resolve.

To understand the Whigs’ decline, examine the structural weaknesses that made them particularly vulnerable to internal strife. Unlike the Democratic Party, which had a strong organizational backbone and a broad base of support, the Whigs were a coalition of disparate interests—business elites, evangelical reformers, and anti-Jackson Democrats—united more by what they opposed than by a shared vision. When the slavery issue became the dominant political question of the 1850s, this fragile alliance crumbled. Leaders like Henry Clay, often referred to as the “Great Compromiser,” had previously held the party together through his skill in brokering deals, but by 1852, Clay was gone, and no figure of comparable stature emerged to fill the void. The Whigs’ lack of strong leadership left them rudderless in a time of crisis.

A comparative analysis of the Whigs and their rivals underscores the fatal consequences of their internal divisions. The Democratic Party, though not immune to sectional tensions, managed to maintain unity by appealing to a broad range of voters through issues like states’ rights and economic populism. The emerging Republican Party, on the other hand, capitalized on the Whigs’ collapse by offering a clear, uncompromising stance against the expansion of slavery. The Whigs, trapped between these two forces, failed to adapt. Their inability to coalesce around a coherent platform on slavery alienated both Northern and Southern voters, leaving them politically isolated. By the mid-1850s, the party had effectively dissolved, with its members defecting to the Republicans, the Know-Nothing Party, or the Democrats.

In practical terms, the Whigs’ decline offers a cautionary tale for modern political parties: unity and leadership are non-negotiable in times of crisis. For parties today grappling with divisive issues, the Whig example underscores the importance of fostering internal dialogue, crafting inclusive platforms, and cultivating strong leaders capable of bridging ideological gaps. While the specifics of the slavery debate are unique to the 19th century, the broader lesson remains relevant: a party that fails to address its internal contradictions risks becoming a historical footnote. The Whigs’ downfall was not inevitable, but their inability to adapt to the changing political landscape sealed their fate, leaving them as a stark reminder of what happens when division and weak leadership prevail.

Summerville, SC: Uncovering the Political Leanings of a Southern Town

You may want to see also

Election of 1852: Franklin Pierce's victory as a Democrat signaled the Whigs' inability to compete

The 1852 presidential election marked a turning point in American political history, as Franklin Pierce’s decisive victory as a Democrat exposed the fatal weaknesses of the Whig Party. Pierce secured 27 of the 31 states, capturing 50.9% of the popular vote and 254 electoral votes, while Whig candidate Winfield Scott managed only 43.9% of the popular vote and a mere 42 electoral votes. This lopsided outcome was not merely a triumph for the Democrats but a stark demonstration of the Whigs’ inability to coalesce around a coherent platform or inspire broad national support. The election revealed deep fractures within the Whig Party, particularly over the issue of slavery, which the Democrats exploited effectively.

To understand the Whigs’ collapse, consider their strategic missteps in the 1852 campaign. The party nominated General Winfield Scott, a war hero but a political novice, whose aristocratic demeanor alienated many voters. In contrast, Pierce, a former senator from New Hampshire, positioned himself as a moderate on slavery, appealing to both Northern and Southern Democrats. The Whigs, meanwhile, failed to articulate a clear stance on the expansion of slavery into new territories, a divisive issue that the Democrats navigated with greater finesse. This ambiguity cost the Whigs critical support in both the North and South, as voters sought leadership with a definitive vision.

A comparative analysis of the two parties’ campaign strategies further highlights the Whigs’ decline. The Democrats ran a disciplined, issue-focused campaign, emphasizing national unity and economic prosperity. They also capitalized on the Whigs’ internal divisions, portraying them as a party in disarray. The Whigs, on the other hand, struggled to unify their base, with factions like the Conscience Whigs opposing slavery expansion and Cotton Whigs supporting it. This internal conflict undermined their ability to present a cohesive message, leaving them vulnerable to Democratic attacks.

The 1852 election served as a harbinger of the Whig Party’s eventual dissolution in 1854. Pierce’s victory not only solidified Democratic dominance but also accelerated the realignment of American politics around the slavery issue. The Whigs’ failure to adapt to this shifting landscape rendered them obsolete, paving the way for the emergence of the Republican Party as the primary opposition to the Democrats. For historians and political analysts, the 1852 election offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of ideological rigidity and the importance of adaptability in a rapidly changing political environment.

Practical takeaways from this historical event include the critical role of issue clarity and party unity in electoral success. Modern political parties can learn from the Whigs’ demise by prioritizing internal cohesion and developing platforms that resonate with diverse constituencies. Additionally, candidates must be mindful of their public image and messaging, as Scott’s elitist persona contrasted unfavorably with Pierce’s relatable demeanor. By studying the 1852 election, contemporary strategists can avoid the pitfalls that led to the Whigs’ downfall and build more resilient political organizations.

Exploring the UK's Largest Political Parties: Power, Influence, and Impact

You may want to see also

Sectional Tensions: North-South conflicts over slavery eroded Whig unity and public support

The 1852 election marked a turning point in American politics, as the Whig Party, once a formidable force, failed to secure the presidency and began its irreversible decline. At the heart of this collapse lay the deepening sectional tensions between the North and the South over slavery, an issue that fractured Whig unity and eroded public support. Unlike the Democratic Party, which could appeal to both pro-slavery Southerners and anti-slavery Northerners through ambiguous platforms, the Whigs struggled to reconcile their diverse constituencies. This inability to navigate the slavery question ultimately sealed their fate.

Consider the Whigs’ ideological foundation: a party born from opposition to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, they championed economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong federal government. However, these principles masked a fatal flaw—their membership spanned both free and slave states, each with diametrically opposed views on slavery. Northern Whigs increasingly aligned with anti-slavery sentiments, while Southern Whigs clung to the institution as essential to their agrarian economy. The Compromise of 1850, intended to ease tensions, only exacerbated divisions within the party. Northern Whigs viewed it as a concession to slavery, while Southern Whigs saw it as insufficient protection for their interests.

The 1852 election exemplified this fragmentation. The Whigs nominated General Winfield Scott, a war hero with moderate views on slavery, hoping to appeal to both sections. However, Scott’s platform failed to satisfy either side. Northern abolitionists found him too conciliatory, while Southern slaveholders distrusted his ties to the North. Meanwhile, the Democrats nominated Franklin Pierce, a Northerner with Southern sympathies, who successfully rallied both regions under a pro-Union, pro-slavery stance. The Whigs’ inability to present a cohesive message on slavery resulted in a devastating loss, with Scott winning only four states.

The takeaway is clear: the Whigs’ downfall was not merely a result of poor leadership or strategic missteps but a symptom of their structural inability to address the slavery question. As sectional tensions intensified, the party’s attempt to straddle the divide became untenable. By contrast, the Democrats’ willingness to prioritize party unity over moral clarity allowed them to survive—and thrive—in the tumultuous decade leading up to the Civil War. The Whigs’ collapse serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of ignoring fundamental ideological rifts within a political organization.

To understand the Whigs’ demise, one must recognize the practical implications of their failure. Unlike the Democrats, who could leverage regional loyalties, the Whigs lacked a unifying cause beyond opposition to Jacksonian democracy. As slavery became the defining issue of the era, their inability to forge a coherent stance alienated voters on both sides. For instance, Northern Whigs lost support to the emerging Free Soil Party, while Southern Whigs defected to the Democrats or the short-lived Know-Nothing Party. This erosion of support was not gradual but precipitous, culminating in the party’s dissolution by the late 1850s. The lesson for modern political parties is stark: ignoring divisive issues or attempting to appease all factions can lead to irrelevance and collapse.

Understanding Political Party Structures: Key Organizational Groups Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rise of Republicans: The new Republican Party absorbed former Whigs opposed to slavery expansion

The 1852 presidential election marked the final gasp of the Whig Party, a once-dominant force in American politics. Their candidate, Winfield Scott, suffered a crushing defeat, winning only four states. This debacle exposed the Whigs' fatal flaw: their inability to reconcile internal divisions over slavery. While some Whigs, like Abraham Lincoln, staunchly opposed its expansion, others, particularly in the South, were more ambivalent or even supportive. This ideological fracture left the party vulnerable to collapse.

The vacuum created by the Whigs' demise was swiftly filled by a new political force: the Republican Party. Founded in 1854, the Republicans emerged as a coalition united by a singular, defining principle: opposition to the expansion of slavery into the western territories. This clear stance attracted disaffected Whigs who had grown disillusioned with their party's equivocation on the slavery issue.

The Republican Party's rise wasn't merely a rebranding of Whig ideals. It represented a fundamental shift in American politics. The Whigs, despite their economic nationalism and internal improvements platform, had failed to address the moral and political crisis posed by slavery. The Republicans, by contrast, directly confronted this issue, appealing to a growing abolitionist sentiment in the North. They framed slavery expansion as a threat to both free labor and the principles of liberty enshrined in the Declaration of Independence.

This strategic focus on slavery's containment proved immensely successful. The Republicans rapidly gained support in the North, drawing not only former Whigs but also members of the Free Soil Party and other anti-slavery factions. Their message resonated with a populace increasingly polarized by the slavery debate. The 1856 election, though ultimately won by Democrat James Buchanan, demonstrated the Republicans' rapid ascent, with John C. Fremont securing a substantial portion of the popular vote.

The Republican Party's absorption of anti-slavery Whigs was a crucial factor in its meteoric rise. By providing a clear and principled alternative to the crumbling Whig Party, the Republicans capitalized on the growing discontent with slavery's influence on American politics. This strategic maneuver not only ensured the party's survival but also set the stage for its eventual dominance in the post-Civil War era. The Republicans' unwavering opposition to slavery expansion became a rallying cry, ultimately leading to the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and the beginning of a new chapter in American history.

Volunteering for a Political Party: A Step-by-Step Guide to Getting Involved

You may want to see also

Legacy of Compromise: Failed compromises like the Compromise of 1850 weakened Whig political relevance

The Compromise of 1850, intended to resolve sectional tensions over slavery, instead exposed the fatal fragility of the Whig Party. By attempting to appease both Northern and Southern factions, Whig leaders like Henry Clay crafted a compromise that satisfied no one. The Fugitive Slave Act, in particular, alienated Northern Whigs, who viewed it as a betrayal of their antislavery principles. Southern Whigs, meanwhile, felt the compromise conceded too much to the North. This internal schism transformed the Whigs from a party of compromise into a party of contradiction, unable to articulate a coherent vision for the nation’s future.

Consider the Whig Party’s platform as a prescription for national unity, with the Compromise of 1850 as its key ingredient. Like a poorly dosed medication, it exacerbated the underlying condition rather than curing it. Northern Whigs, who had supported the party for its economic modernization policies, found themselves at odds with its pro-Southern concessions. Southern Whigs, already skeptical of federal authority, saw the compromise as a weak attempt to placate abolitionists. The result? A political party split at the seams, its relevance diminishing with each passing election cycle.

To understand the Whigs’ decline, compare their strategy to that of the emerging Republican Party. While the Whigs sought to paper over differences, the Republicans took a clear stance against the expansion of slavery. This decisive approach resonated with Northern voters, who increasingly viewed compromise as complicity. The Whigs, by contrast, became the embodiment of political indecision, their legacy of compromise a liability rather than an asset. By 1852, the party’s inability to adapt to the nation’s shifting moral and political landscape sealed its fate.

Practical takeaway: Compromise, when rooted in ambiguity rather than principle, can erode trust and weaken institutions. For modern political parties, the Whig example serves as a cautionary tale. Attempting to straddle divisive issues without a clear moral or ideological framework risks alienating core constituencies. Instead, parties must balance pragmatism with conviction, ensuring that compromises advance their core values rather than dilute them. The Whigs’ failure to do so transformed them from a dominant political force into a historical footnote.

Political Parties' Influence: Shaping Immigration Policies and National Narratives

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Whig Party effectively collapsed after the 1852 election due to internal divisions over slavery and the rise of the Republican Party.

The Whig Party dissolved due to irreconcilable differences among its members over the issue of slavery, particularly after the Compromise of 1850 failed to unite the party.

General Winfield Scott was the last Whig Party candidate to run for president in 1852, but he lost decisively to Democrat Franklin Pierce.

The Republican Party emerged as the primary opposition to the Democrats, absorbing many former Whigs and gaining momentum in the 1850s.

The 1852 election exposed the Whig Party's inability to win national support, as Winfield Scott's defeat highlighted its lack of unity and appeal, accelerating its decline.

![By Michael F. Holt - The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics (1999-07-02) [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51TQpKNRjoL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![General Election, 1852. Poll Book of the North Lincolnshire Election, with a History of the Election [&C.]. Ed. by T. Fricker 1852 Leather Bound](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)