The question of which political party nonvoters typically support is complex and often misunderstood, as nonvoters, by definition, do not participate in elections, making their political leanings difficult to measure directly. However, studies suggest that nonvoters tend to be disproportionately younger, less affluent, and more racially diverse than voters, demographics that often align with progressive or left-leaning policies. Despite this, nonvoters are not a monolithic group, and their political preferences can vary widely based on factors such as geographic location, education, and socioeconomic status. While some nonvoters may lean toward Democratic or progressive platforms due to their demographic characteristics, others may feel alienated by the political system altogether, lacking strong ties to any party. Understanding the political inclinations of nonvoters is crucial, as their potential engagement could significantly shift electoral outcomes, yet their silence remains a challenge for researchers and policymakers alike.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Demographic Analysis: Examines age, race, income, education, and geographic factors influencing nonvoters' political leanings

- Issue Priorities: Identifies key issues (e.g., healthcare, economy) nonvoters care about but don’t vote for

- Party Alienation: Explores why nonvoters feel disconnected from major political parties and their platforms

- Voting Barriers: Investigates systemic obstacles (e.g., registration, access) preventing nonvoters from participating

- Apathy vs. Protest: Differentiates between nonvoters who are disengaged and those boycotting the system

Demographic Analysis: Examines age, race, income, education, and geographic factors influencing nonvoters' political leanings

Nonvoters, often overlooked in political discourse, represent a diverse and complex demographic with varying political leanings. Understanding their preferences requires a nuanced analysis of age, race, income, education, and geographic factors. For instance, younger nonvoters aged 18-29, who constitute a significant portion of this group, tend to lean more progressive, favoring policies like student debt relief and climate action. However, their turnout rates are consistently lower compared to older age groups, often due to disillusionment with the political system or logistical barriers.

Race and ethnicity play a pivotal role in shaping nonvoters' political inclinations. Studies show that non-white nonvoters, particularly Black and Hispanic individuals, often align with Democratic policies on issues like healthcare and immigration. Yet, systemic barriers such as voter ID laws and lack of representation disproportionately affect these communities, contributing to their underrepresentation at the polls. Conversely, white nonvoters exhibit a broader ideological spectrum, with some leaning conservative on fiscal issues while others remain disengaged due to apathy or distrust in government institutions.

Income and education levels further stratify nonvoters' political leanings. Low-income individuals, regardless of race, often support policies addressing economic inequality, such as minimum wage increases or affordable housing. However, financial instability and lack of access to reliable information can hinder their political participation. Similarly, nonvoters with lower educational attainment are less likely to engage in politics, though those who do often prioritize local issues like job creation and public safety. In contrast, highly educated nonvoters may abstain due to dissatisfaction with the two-party system, seeking alternatives outside mainstream politics.

Geography is another critical factor, as nonvoters in urban areas tend to lean left, while those in rural regions often lean right. Urban nonvoters are more likely to support progressive social policies, whereas rural nonvoters prioritize issues like gun rights and agricultural subsidies. However, both groups share common challenges, such as limited access to polling places or disillusionment with candidates who fail to address their specific needs. Regional disparities also play a role; for example, nonvoters in the South are more likely to identify as conservative, while those in the Northeast and West Coast lean liberal.

To effectively engage nonvoters, campaigns must tailor their strategies to these demographic nuances. For young nonvoters, leveraging social media and addressing student debt could boost participation. For minority communities, removing systemic barriers and increasing representation in political messaging is essential. Low-income and less educated nonvoters would benefit from localized, issue-focused outreach, while highly educated nonvoters might respond to platforms advocating political reform. By acknowledging these differences, policymakers and activists can bridge the gap between nonvoters and the political process, potentially reshaping electoral outcomes.

Exploring France's Diverse Political Landscape: A Comprehensive Party Count

You may want to see also

Issue Priorities: Identifies key issues (e.g., healthcare, economy) nonvoters care about but don’t vote for

Nonvoters, often dismissed as apathetic or disengaged, actually care deeply about specific issues—they simply don’t see voting as the solution. Surveys consistently show that healthcare ranks high on their list of concerns, particularly among younger nonvoters aged 18–29. For them, the rising cost of prescription drugs, lack of mental health services, and the burden of student debt intersecting with healthcare affordability create a sense of urgency. Yet, they perceive political parties as failing to address these issues with tangible, immediate solutions, opting instead for vague promises or partisan bickering. This disconnect turns their passion into frustration, leaving them feeling powerless at the ballot box.

The economy is another critical issue for nonvoters, especially those in low-income brackets or precarious employment. They worry about stagnant wages, housing affordability, and the gig economy’s lack of job security. For instance, a 2022 Pew Research study found that 62% of nonvoters cited economic inequality as a top concern, compared to 52% of voters. However, they often view political debates about the economy as abstract—focused on GDP growth or corporate tax rates rather than the day-to-day struggles of making ends meet. Without policies that directly address their lived experiences, such as rent control or universal basic income, these voters see little reason to participate in a system they believe ignores them.

Environmental concerns also resonate with nonvoters, particularly in communities disproportionately affected by pollution or climate change. For example, residents of areas like Flint, Michigan, or Louisiana’s Cancer Alley are acutely aware of environmental injustice but feel their voices are drowned out by corporate interests. While they support green initiatives, they’re skeptical of politicians who prioritize industry profits over public health. This skepticism deepens when parties fail to deliver on campaign promises, such as the delayed implementation of clean water programs or insufficient funding for renewable energy projects. As a result, these voters disengage, believing their votes won’t change systemic failures.

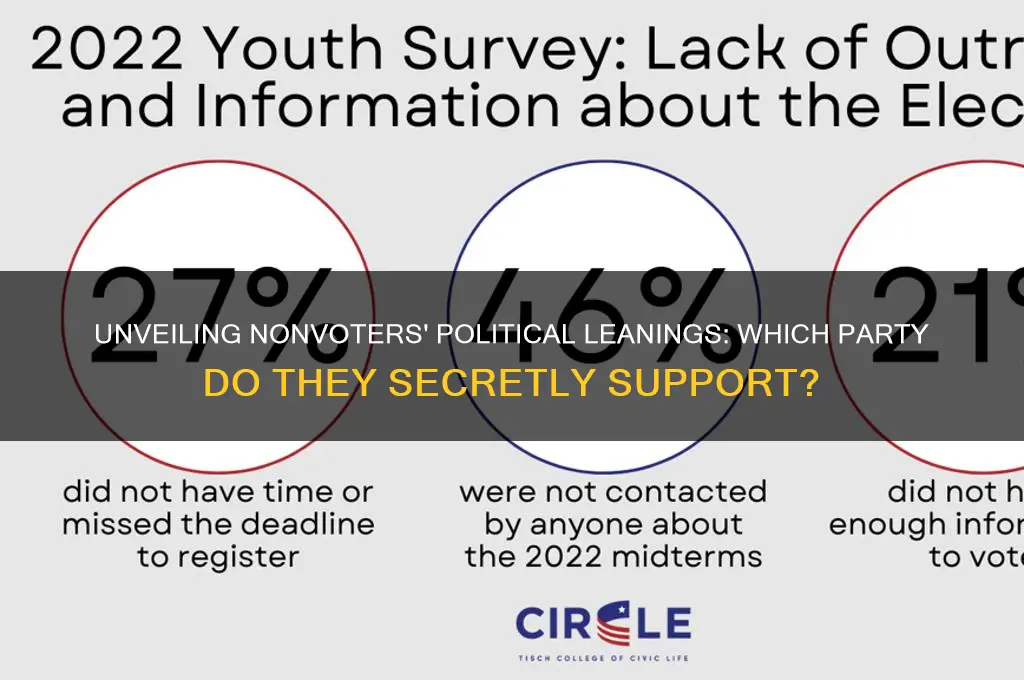

Education reform is another issue nonvoters care about, particularly parents and young adults burdened by student loan debt. They advocate for equitable school funding, affordable higher education, and vocational training programs. However, they perceive political discussions about education as overly focused on standardized testing or charter schools, rather than addressing the root causes of inequality. For instance, a 2021 study by the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) found that 43% of nonvoters aged 18–24 wanted more investment in community colleges, yet felt neither party prioritized this. Without concrete action, their enthusiasm for change turns into disillusionment, reinforcing their decision to stay home on Election Day.

To re-engage nonvoters, political parties must bridge the gap between rhetoric and reality. This means crafting policies that directly address their priorities—such as capping insulin prices, implementing rent control, or creating green jobs in underserved communities. It also requires transparent communication about how these policies will be funded and implemented. For example, a pilot program offering free community college tuition in a single state could serve as a proof of concept, demonstrating tangible benefits to skeptical nonvoters. By showing that their concerns are not just heard but acted upon, parties can transform frustration into participation, turning nonvoters into a powerful electoral force.

Empowering the Masses: Which Political Party Champions 'Power to the People'?

You may want to see also

Party Alienation: Explores why nonvoters feel disconnected from major political parties and their platforms

Nonvoters, often dismissed as apathetic or disengaged, frequently cite a profound sense of alienation from major political parties as their primary reason for abstaining. This disconnect isn’t merely a lack of interest but a deliberate rejection of platforms that fail to resonate with their lived experiences. For instance, surveys reveal that 40% of nonvoters feel neither party addresses issues like economic inequality or healthcare affordability in ways that align with their needs. This alienation is compounded by the perception that parties prioritize partisan bickering over tangible solutions, leaving nonvoters feeling like spectators in a system designed to exclude them.

Consider the case of younger nonvoters, aged 18–29, who are less likely to vote than older demographics. Many in this group express frustration with parties that promise progressive change but deliver incrementalism at best. For example, while climate change ranks as a top concern for this cohort, they often view party platforms as insufficiently bold or urgent. This mismatch between rhetoric and action fosters a sense of betrayal, reinforcing the belief that their voices are irrelevant in the political process. Practical steps to bridge this gap could include parties adopting more inclusive policy-making processes, such as town halls or digital forums, to directly engage nonvoters in shaping their agendas.

Persuasively, it’s worth noting that nonvoters aren’t a monolithic bloc; their reasons for alienation vary widely. Some feel marginalized by parties that ignore rural or working-class concerns, while others reject the polarizing rhetoric that dominates campaigns. A comparative analysis of nonvoters in the U.S. and Europe highlights how proportional representation systems can reduce alienation by offering voters more diverse party options. In contrast, winner-takes-all systems often leave nonvoters feeling their only choices are between two unsatisfactory alternatives. This structural issue suggests that electoral reform, not just better messaging, may be necessary to re-engage alienated voters.

Descriptively, the language and imagery used by major parties often contribute to this alienation. Campaign ads that rely on fearmongering or simplistic slogans alienate voters seeking nuanced, empathetic leadership. For instance, phrases like “Make America Great Again” or “Take Back Control” can feel exclusionary to those who don’t identify with the implied nostalgia or nationalism. Parties could adopt more inclusive narratives that acknowledge the complexities of modern life, such as the challenges of automation, mental health, or housing affordability. Such a shift would signal to nonvoters that their struggles are seen and valued.

In conclusion, party alienation among nonvoters stems from a systemic failure to address their concerns authentically and inclusively. By understanding the specific grievances of different nonvoter groups—whether young adults, rural residents, or working-class families—parties can begin to rebuild trust. Practical measures, from policy co-creation to more empathetic messaging, offer pathways to re-engagement. Ultimately, the question isn’t just what party nonvoters support, but how parties can evolve to earn their support.

Understanding SD: Sustainable Development's Role in Modern Political Strategies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Voting Barriers: Investigates systemic obstacles (e.g., registration, access) preventing nonvoters from participating

Nonvoters, often labeled as apathetic or disengaged, are in fact a diverse group whose absence from the polls is frequently rooted in systemic barriers rather than lack of interest. Research indicates that nonvoters tend to lean more progressive, with younger, lower-income, and minority populations disproportionately represented. However, their potential political impact remains untapped due to obstacles that hinder their ability to participate. Understanding these barriers is crucial for addressing the democratic deficit they create.

One of the most pervasive systemic obstacles is voter registration. In the United States, for example, citizens must proactively register to vote, often facing complex processes, strict deadlines, and varying state requirements. This system contrasts sharply with countries like Australia, where automatic registration has led to turnout rates exceeding 90%. In the U.S., registration barriers disproportionately affect young people, minorities, and low-income individuals—groups that often lean Democratic. A 2020 study by the Brennan Center found that 1 in 4 eligible voters is not registered, with registration rates among 18- to 29-year-olds lagging significantly behind older demographics. Simplifying registration through automatic or same-day options could dramatically increase participation among these groups.

Access to polling places is another critical barrier. In many areas, polling locations are scarce in low-income neighborhoods, requiring voters to travel long distances or wait in excessively long lines. During the 2020 election, for instance, predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods in states like Georgia and Texas faced wait times up to three times longer than wealthier, whiter areas. Additionally, strict voter ID laws, while ostensibly aimed at preventing fraud, often disenfranchise those without access to required documents, such as state-issued IDs. These access issues not only deter voting but also reinforce political marginalization, as the voices of affected communities remain unheard in policy decisions.

Finally, the structure of election days itself poses a barrier. Unlike many democracies that hold elections on weekends or make Election Day a holiday, the U.S. conducts voting on a Tuesday, a workday for most. This scheduling disproportionately affects hourly workers, who often cannot afford to take time off to vote. Implementing measures like early voting, mail-in ballots, and making Election Day a federal holiday could alleviate these constraints. For example, states with robust early voting options, such as Colorado and Oregon, consistently see higher turnout rates, particularly among younger and lower-income voters.

Addressing these systemic barriers requires a multifaceted approach. Policymakers must prioritize reforms that streamline registration, expand access to polling places, and modernize voting procedures. By removing these obstacles, we can unlock the political potential of nonvoters, ensuring that their voices—often aligned with progressive ideals—are reflected in the democratic process. The question is not whether nonvoters care, but whether the system allows them to participate.

Joining a Political Party: Benefits, Influence, and Community Engagement

You may want to see also

Apathy vs. Protest: Differentiates between nonvoters who are disengaged and those boycotting the system

Nonvoters are often lumped into a single category, but their motivations for abstaining from the ballot box differ sharply. Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone analyzing electoral trends or seeking to engage these groups. At one end of the spectrum are the apathetic nonvoters, those who are disengaged from the political process due to a lack of interest, knowledge, or perceived relevance. At the other end are protest nonvoters, who consciously boycott elections as a form of political statement, often driven by disillusionment with the system or a lack of viable representation. These two groups, though both absent from the polls, represent fundamentally different relationships with democracy.

Consider the apathetic nonvoter: this group often includes younger adults, particularly those aged 18–24, who may feel disconnected from political discourse. Studies show that this demographic frequently lacks awareness of candidates, policies, or even voting procedures. For instance, a 2020 Pew Research Center study found that 40% of nonvoters cited a lack of interest or forgetting to vote as their primary reason for abstaining. Engaging this group requires targeted education campaigns, simplified voter registration processes, and platforms that address issues directly impacting their lives, such as student debt or climate change. Practical steps include hosting voter registration drives at high schools and colleges, or using social media to disseminate bite-sized, non-partisan political information.

In contrast, protest nonvoters are often more politically aware but deeply disillusioned. This group frequently includes older, more educated individuals who feel the political system is corrupt, unresponsive, or dominated by corporate interests. For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, some left-leaning voters refused to support either major candidate, viewing both as insufficiently progressive. Protest nonvoters may also belong to marginalized communities that historically face systemic barriers to representation. Engaging this group requires systemic reforms, such as campaign finance overhaul or ranked-choice voting, to restore their faith in the system. Encouraging participation in local elections or grassroots movements can also provide a sense of agency and impact.

The distinction between apathy and protest has significant implications for political parties. Apathetic nonvoters are a largely untapped reservoir of potential support, particularly for parties that can simplify their messaging and address pressing personal concerns. Protest nonvoters, however, demand more radical changes—parties must prove their commitment to transparency, inclusivity, and meaningful reform to win their trust. For instance, a party advocating for anti-corruption measures or electoral reform might resonate with protest nonvoters, while one focusing on civic education and youth outreach could appeal to the apathetic.

Ultimately, treating nonvoters as a monolithic bloc overlooks the nuanced reasons behind their abstention. By distinguishing between apathy and protest, political actors can tailor strategies to re-engage these groups effectively. For apathetic nonvoters, the solution lies in education and accessibility; for protest nonvoters, it’s about systemic change and rebuilding trust. Both approaches are essential for strengthening democratic participation and ensuring that the voices of all citizens, whether cast in ballots or withheld in protest, are acknowledged and addressed.

Decline of Political Machines: Factors Weakening Party Control and Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Nonvoters do not typically support any specific political party, as their decision not to vote often stems from apathy, disillusionment, or disengagement from the political process rather than partisan affiliation.

Studies suggest nonvoters are often more ideologically diverse, but some research indicates they may lean slightly more liberal or independent, though this varies by demographic and region.

While some nonvoters may sympathize with third-party or independent candidates, their non-participation in elections means they do not actively support any party or candidate, including third-party options.

![The Independent [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71I5a143UEL._AC_UY218_.jpg)