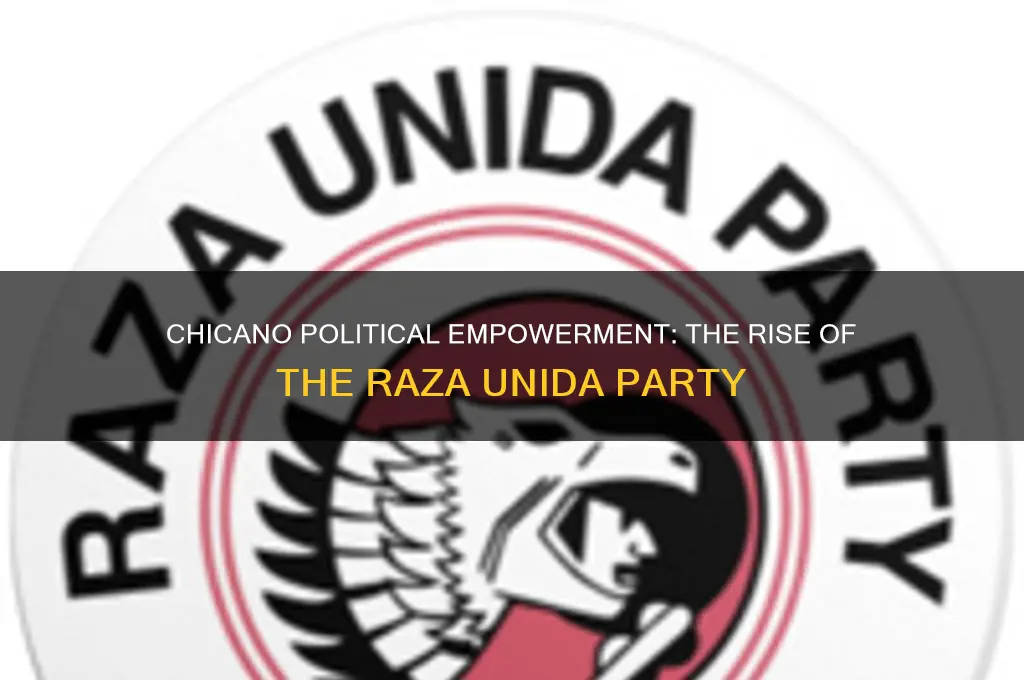

The Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, a pivotal era of civil rights activism among Mexican Americans, led to the formation of several political organizations aimed at addressing systemic inequalities and promoting self-determination. Among these, the Raza Unida Party (RUP) emerged as the most prominent political party founded by Chicanos. Established in 1970 in Crystal City, Texas, the RUP sought to empower Mexican American communities by advocating for land rights, educational reform, and political representation. While the party achieved notable successes, including electing local officials in Texas, its influence waned by the late 1970s due to internal divisions and limited resources. Nonetheless, the RUP remains a significant symbol of Chicano political mobilization and the broader struggle for racial and social justice.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO): Radical Chicano group advocating for self-determination and political empowerment in the 1960s

- La Raza Unida Party: Formed in 1970, focused on Chicano political representation and cultural pride

- Chicano Movement Goals: Sought civil rights, education reform, and economic justice for Mexican Americans

- Key Leaders: Figures like Rodolfo Gonzales and José Ángel Gutiérrez played pivotal roles

- Legacy and Impact: Inspired ongoing activism and shaped modern Latino political engagement in the U.S

Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO): Radical Chicano group advocating for self-determination and political empowerment in the 1960s

The Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) emerged in the 1960s as a radical Chicano group, born out of the frustration and disillusionment with mainstream political parties that failed to address the systemic inequalities faced by Mexican Americans. Unlike traditional political parties, MAYO was a grassroots movement focused on self-determination, cultural pride, and political empowerment. Its formation marked a turning point in Chicano activism, as it sought to challenge not only external oppression but also internal apathy within the community. By organizing youth, MAYO aimed to create a new generation of leaders who would fight for social justice on their own terms.

MAYO’s approach was distinctly confrontational and unapologetic. They rejected assimilationist ideologies, instead advocating for a Chicano identity rooted in indigenous and Mexican heritage. This included promoting bilingual education, celebrating cultural traditions, and demanding representation in political institutions. Their tactics ranged from community organizing and voter registration drives to more radical actions like protests and boycotts. For instance, MAYO played a pivotal role in the 1968 Denver school walkouts, where thousands of students protested discriminatory practices in public schools. These actions demonstrated their commitment to direct action as a means of achieving political change.

One of the key takeaways from MAYO’s strategy is the importance of youth mobilization in social movements. By targeting young Mexican Americans, the organization tapped into a demographic often overlooked by mainstream politics. They provided a platform for young Chicanos to voice their grievances and take ownership of their futures. This focus on youth not only ensured the sustainability of the movement but also fostered a sense of collective identity and purpose. Practical tips for modern activists include leveraging social media to engage youth, creating safe spaces for dialogue, and integrating cultural education into political organizing.

Comparatively, MAYO’s radicalism set it apart from more moderate Chicano organizations of the time, such as the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). While LULAC focused on gradual reform within the existing political system, MAYO demanded immediate and transformative change. This divergence highlights the tension between integrationist and separatist ideologies within the Chicano movement. MAYO’s legacy lies in its ability to inspire future generations of activists, including those involved in the Chicano Party, which later formalized the movement’s political aspirations. Their emphasis on self-determination remains a guiding principle for contemporary struggles for racial and social justice.

In conclusion, the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) was more than just a political group; it was a catalyst for Chicano empowerment in the 1960s. Through its radical advocacy and focus on youth, MAYO challenged the status quo and laid the groundwork for future political organizing. Its lessons—mobilize the marginalized, embrace cultural identity, and demand systemic change—are as relevant today as they were decades ago. For anyone studying or engaging in activism, MAYO’s story serves as a reminder that true political power begins with self-determination and community action.

Party Lines and Corruption: How Politics Shapes Public Perception

You may want to see also

La Raza Unida Party: Formed in 1970, focused on Chicano political representation and cultural pride

The Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a transformative period marked by activism, cultural resurgence, and political mobilization. Amid this ferment, the La Raza Unida Party (RUP) emerged in 1970 as a direct response to the systemic exclusion of Mexican Americans from mainstream political institutions. Founded in Crystal City, Texas, often dubbed the "Spinach Capital of the World," the party capitalized on local grievances, such as poor school conditions and economic inequality, to win municipal elections. This grassroots success demonstrated the power of community organizing and set the stage for RUP’s broader mission: to secure political representation and cultural pride for Chicanos nationwide.

At its core, RUP was more than a political party; it was a movement rooted in self-determination. Its platform addressed issues like bilingual education, land rights, and labor protections, reflecting the specific needs of Chicano communities. The party’s slogan, *"Por La Raza todo, Fuera de La Raza nada"* ("For the People everything, Outside the People nothing"), encapsulated its commitment to collective empowerment. By fielding candidates in local, state, and even federal elections, RUP challenged the two-party system’s dominance and forced mainstream politicians to acknowledge Chicano concerns. For instance, in 1972, RUP candidate Ramsey Muñiz garnered over 200,000 votes in the Texas gubernatorial race, a testament to the party’s growing influence.

However, RUP’s impact extended beyond electoral politics. It fostered a cultural renaissance, promoting Chicano art, literature, and history as tools of resistance and identity-building. The party’s annual national conventions became hubs for intellectual exchange, where activists debated strategies and celebrated their heritage. This dual focus on political representation and cultural pride distinguished RUP from other civil rights organizations, as it sought to reclaim not just rights but also dignity and visibility for a marginalized community.

Despite its achievements, RUP faced significant challenges. Internal divisions over ideology and strategy, coupled with external pressures from established parties, weakened its cohesion. By the late 1970s, the party’s influence waned, though its legacy endures. RUP’s pioneering efforts laid the groundwork for future Latino political organizations and inspired generations of activists. Its story serves as a reminder that political change often begins at the local level, fueled by the passion and resilience of those fighting for justice. For anyone studying social movements or seeking to organize marginalized communities, RUP offers invaluable lessons in the interplay between politics, culture, and identity.

Washington's View: Were Political Parties Necessary for American Governance?

You may want to see also

Chicano Movement Goals: Sought civil rights, education reform, and economic justice for Mexican Americans

The Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a transformative force in American history, driven by the collective aspirations of Mexican Americans for equality and justice. While the movement did not formally establish a single political party, it fostered the creation of organizations like the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA) and the Raza Unida Party (RUP). These groups emerged as vehicles to advance the movement’s core goals: civil rights, education reform, and economic justice. Unlike mainstream parties, RUP, for instance, focused exclusively on the needs of Mexican Americans, running candidates in Texas and other states to challenge systemic inequalities. This strategic alignment with grassroots activism highlights how the Chicano Movement sought to reshape political landscapes from within.

Civil rights were at the heart of the Chicano Movement, addressing the pervasive discrimination faced by Mexican Americans in employment, housing, and public accommodations. Activists demanded an end to police brutality and fought for legal protections against racial profiling. The 1968 East L.A. walkouts, where thousands of high school students protested substandard education, exemplify this struggle. These actions paralleled broader civil rights efforts but were uniquely tailored to the Chicano experience, emphasizing cultural pride and self-determination. By leveraging protests, boycotts, and legal challenges, the movement secured key victories, such as the 1975 Laureno Torres v. Texas decision, which outlawed discrimination based on Spanish surnames.

Education reform was another cornerstone of the Chicano Movement, targeting the systemic neglect of Mexican American students. Activists criticized overcrowded classrooms, lack of bilingual instruction, and curricula that ignored Chicano history. The creation of Chicano Studies programs at universities like UC Santa Barbara and UC Berkeley marked a significant achievement, providing academic spaces to explore Mexican American identity and contributions. At the K-12 level, the movement pushed for bilingual education, culminating in the 1974 Lau v. Nichols Supreme Court decision, which mandated schools to address language barriers. These reforms aimed not only to improve educational outcomes but also to empower students with a sense of cultural heritage.

Economic justice was a critical yet often overlooked goal of the Chicano Movement, addressing the poverty and exploitation faced by many Mexican Americans. Farmworkers, led by figures like César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, organized strikes and boycotts to demand fair wages and safe working conditions. The United Farm Workers’ grape boycott of the 1960s became a symbol of this struggle, uniting Chicanos with labor activists nationwide. Beyond agriculture, the movement advocated for job training programs, affordable housing, and small business support to uplift communities. By linking economic empowerment to broader social justice, the Chicano Movement sought to dismantle the structural barriers that perpetuated inequality.

While the Chicano Movement did not form a single political party, its legacy endures in the organizations and policies it inspired. The Raza Unida Party, though short-lived, demonstrated the power of community-driven politics, winning local elections and influencing mainstream parties to address Chicano concerns. Today, the movement’s goals remain relevant, as Mexican Americans continue to fight for civil rights, education equity, and economic opportunity. By studying its strategies and achievements, activists can draw practical lessons: build coalitions, prioritize grassroots organizing, and center cultural identity in the pursuit of justice. The Chicano Movement’s impact serves as a blueprint for ongoing struggles, reminding us that political change begins with collective action.

Switching Political Parties in Florida: A Step-by-Step Guide to Change

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Leaders: Figures like Rodolfo Gonzales and José Ángel Gutiérrez played pivotal roles

The Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a transformative period for Mexican Americans, marked by a quest for civil rights, cultural pride, and political empowerment. At its core were visionary leaders who galvanized communities and shaped the movement’s trajectory. Among them, Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales and José Ángel Gutiérrez stand out for their distinct yet complementary roles in fostering political consciousness and organizing Chicanos into a formidable force.

Rodolfo Gonzales, a former boxer turned activist, embodied the spirit of resistance and self-determination. His 1967 epic poem, *“I Am Joaquín”*, became a rallying cry for Chicanos, articulating their shared history of oppression and aspirations for liberation. Gonzales founded the Crusade for Justice in Denver, which served as both a cultural hub and a political incubator. Through this organization, he advocated for educational reform, labor rights, and the preservation of Chicano heritage. His leadership was deeply rooted in grassroots mobilization, emphasizing the importance of local action as the foundation for broader systemic change.

In contrast, José Ángel Gutiérrez brought a more structured, institutional approach to Chicano political organizing. As a co-founder of the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) and later the Raza Unida Party, Gutiérrez sought to translate cultural pride into electoral power. The Raza Unida Party, established in 1970, was a bold experiment in third-party politics, aiming to represent the interests of Chicanos who felt marginalized by the Democratic and Republican parties. Gutiérrez’s strategic focus on voter registration, candidate recruitment, and coalition-building demonstrated the potential for Chicanos to shape policy directly through the political system.

While Gonzales and Gutiérrez differed in their methods—one prioritizing cultural revival and grassroots activism, the other emphasizing electoral politics—their efforts were mutually reinforcing. Gonzales’s work laid the ideological groundwork, inspiring a generation to embrace their identity and demand respect. Gutiérrez built on this foundation by creating mechanisms for political participation, ensuring that Chicano voices were heard in the halls of power. Together, they exemplified the dual imperatives of the movement: cultural affirmation and political empowerment.

Their legacies endure in the ongoing struggles for Latino rights and representation. Gonzales’s emphasis on community-driven change reminds us that true transformation begins at the local level, while Gutiérrez’s focus on institutional power underscores the importance of engaging with the political system. For contemporary activists, their stories offer a blueprint: cultivate pride in your heritage, organize at the grassroots, and leverage political institutions to effect change. In a time when Latino political influence continues to grow, the lessons of these leaders remain as relevant as ever.

How Presidential Leadership Strengthens Political Party Unity and Influence

You may want to see also

Legacy and Impact: Inspired ongoing activism and shaped modern Latino political engagement in the U.S

The Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, while not forming a single unified political party, gave rise to organizations like the Raza Unida Party (RUP), which sought to address the specific needs of Mexican Americans. Though the RUP’s electoral successes were limited, its legacy lies in its ability to galvanize Latino political consciousness. By challenging systemic discrimination and advocating for self-determination, the movement laid the groundwork for modern Latino political engagement, demonstrating the power of grassroots organizing and cultural pride in shaping political identity.

Consider the ripple effect of the Chicano Movement’s activism. It inspired the creation of Latino-focused political action committees, voter registration drives, and advocacy groups that continue to operate today. For instance, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the National Council of La Raza (now UnidosUS) trace their roots to the movement’s emphasis on civil rights and political representation. These organizations have been instrumental in mobilizing Latino voters, particularly in swing states, where their turnout can sway election outcomes. Practical tip: Engage with local Latino advocacy groups to understand their voter education initiatives and volunteer in get-out-the-vote campaigns during election seasons.

Analytically, the Chicano Movement’s focus on cultural identity and political empowerment reshaped the Latino electorate’s self-perception. By embracing terms like *Chicano* and *Raza*, the movement reclaimed a shared heritage that transcended national origins, fostering a pan-Latino solidarity. This unity is evident in modern political coalitions, such as the Latino Victory Project, which supports Latino candidates across party lines. Comparative analysis reveals that while the Chicano Movement was rooted in Mexican American experiences, its strategies—like community-based organizing and cultural celebration—have been adopted by other Latino subgroups, from Puerto Ricans to Salvadorans, amplifying their collective political voice.

Persuasively, the movement’s legacy underscores the importance of intersectionality in Latino political engagement. Chicano activists addressed not only racial discrimination but also economic inequality, education disparities, and labor rights—issues that remain central to Latino advocacy today. For example, the fight for farmworkers’ rights led by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, both tied to the Chicano Movement, continues to inspire campaigns for fair wages and workplace protections. To maximize impact, modern activists should integrate these historical lessons into contemporary campaigns, linking immigration reform, healthcare access, and education funding to the broader struggle for Latino empowerment.

Descriptively, the Chicano Movement’s cultural expressions—murals, music, and literature—remain vivid symbols of resistance and pride, influencing modern Latino political messaging. Think of the iconic *La Virgen de Guadalupe* imagery in protests or the use of *corridos* in campaign rallies. These cultural touchstones not only mobilize communities but also humanize political demands, making them more relatable and compelling. Takeaway: Incorporate cultural elements into political campaigns to deepen emotional connections with Latino voters, ensuring that activism resonates beyond policy proposals. By honoring the Chicano Movement’s legacy, today’s advocates can build on its foundation, driving meaningful change in an increasingly diverse political landscape.

Politics Over Prejudice: Understanding Why Not All Attacks Are Hate Crimes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Chicanos formed the Chicano Movement, which was not a single political party but a social and political movement advocating for civil rights, cultural pride, and political empowerment. However, some Chicanos later established the Raza Unida Party in the 1970s as a more formal political organization.

Chicanos created the Raza Unida Party to address issues of political underrepresentation, discrimination, and economic inequality that were not being adequately addressed by the mainstream Democratic and Republican parties.

The main goals of the Raza Unida Party included promoting Chicano cultural identity, achieving political representation, improving educational opportunities, and addressing economic disparities faced by the Chicano community.

The Raza Unida Party is no longer a major political force, as it declined in the late 1970s and early 1980s due to internal conflicts and limited electoral success. However, its legacy continues to influence Chicano and Latino political activism and organizations.