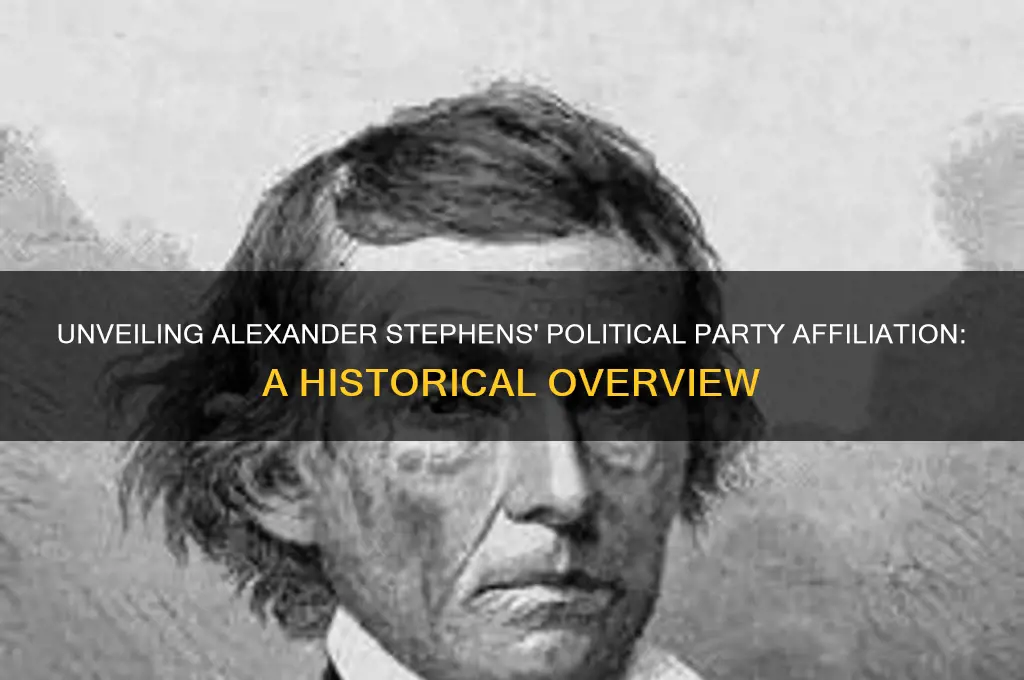

Alexander H. Stephens, a prominent figure in American history, was a member of the Democratic Party. As a politician from Georgia, Stephens served in various capacities, including as a U.S. Representative, Governor, and most notably, as the Vice President of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. His political career was deeply intertwined with the issues of states' rights and slavery, which were central to the Democratic Party's platform in the mid-19th century. Stephens' affiliation with the Democratic Party reflects the complex and often contentious political landscape of the time, particularly in the Southern states.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Political Affiliations: Stephens' initial party alignment before major political shifts

- Role in Party Formation: His involvement in creating or joining new parties

- Ideological Evolution: Changes in Stephens' beliefs affecting party membership

- Key Party Contributions: Significant actions or policies he championed within the party

- Later Political Shifts: Stephens' final party affiliation before retirement or death

Early Political Affiliations: Stephens' initial party alignment before major political shifts

Alexander Stephens, a prominent figure in 19th-century American politics, began his political career with affiliations that reflected the complex and evolving nature of the antebellum South. Initially, Stephens aligned himself with the Whig Party, a decision rooted in his admiration for Henry Clay and his commitment to economic modernization and internal improvements. The Whigs’ emphasis on national unity and their opposition to the extremes of both abolitionism and states’ rights resonated with Stephens’ early political beliefs. This alignment was pragmatic, as the Whigs offered a platform that balanced his regional interests with a broader national vision.

Stephens’ Whig affiliation, however, was not without tension. As sectional divides deepened in the 1840s and 1850s, the party struggled to maintain cohesion. Stephens, a Georgian, found himself increasingly at odds with the party’s Northern wing, particularly on the issue of slavery. His defense of slavery as a "peculiar institution" and his belief in Southern rights began to overshadow his earlier Whig loyalties. This internal conflict foreshadowed the eventual collapse of the Whig Party and Stephens’ own political realignment.

The Compromise of 1850 marked a turning point in Stephens’ early political career. While he initially supported the compromise as a means of preserving the Union, his stance alienated many Southern Whigs who viewed it as a concession to Northern interests. This shift highlighted Stephens’ growing prioritization of Southern unity over party loyalty. By the mid-1850s, as the Whig Party disintegrated, Stephens, like many Southern politicians, sought a new political home that better aligned with his evolving views on states’ rights and slavery.

Stephens’ transition from the Whig Party to the Democratic Party was gradual but inevitable. His support for the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, signaled his alignment with the Democratic Party’s pro-slavery and states’ rights platform. This shift was not merely ideological but also strategic, as the Democrats offered a stronger base of support in the South. By the late 1850s, Stephens had fully embraced the Democratic Party, setting the stage for his later role as Vice President of the Confederate States of America.

In retrospect, Stephens’ early political affiliations reveal a man navigating the turbulent waters of antebellum politics. His initial alignment with the Whigs reflected a desire for national unity and economic progress, but his unwavering commitment to Southern interests ultimately led him to abandon the party. This evolution underscores the fragility of political alliances in an era defined by sectional conflict and the centrality of slavery in American politics. Stephens’ journey from Whig to Democrat is a microcosm of the broader political shifts that culminated in the Civil War.

Farmers Alliance's Legacy: Birth of the Populist Political Party

You may want to see also

Role in Party Formation: His involvement in creating or joining new parties

Alexander Stephens, often referred to as the "Little Giant of the Confederacy," played a pivotal role in party formation throughout his political career. His journey reflects the turbulent political landscape of the mid-19th century, marked by shifting alliances and the rise of new ideologies. Stephens began his career as a Whig, a party that emphasized economic modernization and opposed the expansion of slavery. However, as the Whig Party crumbled in the 1850s, Stephens, like many Southern politicians, sought a new political home that aligned with his pro-slavery and states' rights views.

Stephens’ involvement in party formation became most pronounced during the creation of the Constitutional Union Party in 1860. This party emerged as a response to the growing sectional divide between the North and South. Its platform was deliberately vague, focusing on preserving the Union under the Constitution rather than taking a strong stance on slavery. Stephens, who had previously been a Democrat, saw this party as a pragmatic option to prevent secession. He became one of its leading figures, even serving as its vice presidential candidate in the 1860 election. While the party failed to win the presidency, Stephens’ role in its formation highlights his efforts to find a middle ground in an increasingly polarized nation.

After the Civil War, Stephens’ political journey took another turn as he joined the Conservative Party of Georgia. This party, formed in 1865, aimed to restore Georgia’s political and economic stability while resisting Radical Republican policies during Reconstruction. Stephens’ involvement here underscores his commitment to states' rights and his opposition to federal intervention. His leadership in this party helped shape its agenda, which focused on limiting African American political participation and maintaining white supremacy. While controversial by modern standards, his role in this party’s formation reflects his adaptability in aligning with emerging political movements.

Stephens’ career in party formation is a study in pragmatism and ideological evolution. He moved from the Whigs to the Constitutional Union Party and later to the Conservatives, always prioritizing his region’s interests and his own political survival. His ability to navigate these transitions demonstrates a keen understanding of the political currents of his time. However, it also reveals the limitations of his vision, as he consistently aligned with parties that sought to preserve the status quo, often at the expense of marginalized groups.

In analyzing Stephens’ role in party formation, one takeaway stands out: his political career was defined by his ability to adapt to changing circumstances while remaining firmly rooted in his core beliefs. For those studying party formation, Stephens’ example illustrates the importance of flexibility in a volatile political environment. However, it also serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of prioritizing regional or personal interests over broader principles of equality and justice. Understanding his journey offers valuable insights into the complexities of political realignment and the enduring impact of individual leaders on party dynamics.

Unveiling the Author: Who Wrote 'Politics' in Apex Legends?

You may want to see also

Ideological Evolution: Changes in Stephens' beliefs affecting party membership

Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States of America, underwent a notable ideological evolution that directly influenced his political affiliations. Initially a staunch Whig, Stephens’ early career was marked by his commitment to the principles of the party, which emphasized economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong Union. His shift to the Democratic Party in the 1850s, however, reflected a deepening commitment to states’ rights and Southern interests, particularly in the context of slavery. This transition was not merely a change in party label but a realignment of his core beliefs, driven by the intensifying sectional tensions of the era.

Stephens’ ideological evolution is best understood through the lens of his "Cornerstone Speech" in 1861, where he articulated the Confederacy’s founding ideology. Here, he explicitly rejected his earlier Unionist sentiments, declaring the Confederacy’s cornerstone as the "great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man." This marked a dramatic departure from his Whig roots, where he had once supported Henry Clay’s gradualist approach to slavery. The speech exemplifies how Stephens’ beliefs hardened in response to the political climate, pushing him further into the orbit of the pro-secession Democrats.

To trace Stephens’ ideological shifts, consider the following steps: First, examine his early legislative career (1843–1859) as a Whig, where he championed infrastructure projects and opposed secession. Second, analyze his transition to the Democratic Party during the 1850s, coinciding with his growing defense of slavery and states’ rights. Third, study his role in the Confederacy (1861–1865), where his beliefs crystallized into a radical defense of Southern institutions. This progression reveals how external pressures and personal convictions can reshape political allegiances.

A cautionary note: Stephens’ evolution underscores the dangers of ideological rigidity. His initial pragmatism as a Whig gave way to an uncompromising stance as a Confederate leader, contributing to the nation’s fracture. For modern observers, this serves as a reminder that political beliefs should be adaptable to changing realities, not entrenched in dogma. Stephens’ journey from Unionist to secessionist illustrates the high stakes of ideological transformation in times of crisis.

In conclusion, Stephens’ party membership was not static but a reflection of his evolving beliefs. His shift from Whig to Democrat to Confederate leader mirrors the broader ideological divides of the 19th century. By studying his trajectory, we gain insight into how personal and political forces can reshape one’s worldview, offering both historical context and contemporary relevance. Stephens’ story is a testament to the dynamic interplay between individual conviction and the pressures of the political moment.

How Political Parties Can Empower Your Voice and Shape Your Future

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Party Contributions: Significant actions or policies he championed within the party

Alexander H. Stephens, a prominent figure in 19th-century American politics, was a member of the Democratic Party. His political career, particularly during the antebellum and Civil War eras, was marked by significant contributions that reflected his deep commitment to states' rights and Southern interests. Stephens’ role within the party was both influential and controversial, as he championed policies that would later become central to the Confederacy’s ideology.

One of Stephens’ most notable contributions was his advocacy for states' rights, a principle he believed was essential to preserving the South’s way of life. As a Congressman from Georgia, he consistently argued against federal overreach, particularly in matters of tariffs and internal improvements. His speeches and writings emphasized the sovereignty of individual states, a stance that resonated deeply with Southern Democrats. This ideology would later form the backbone of the Confederate Constitution, which Stephens helped draft as Vice President of the Confederacy.

Another key contribution was his defense of slavery as a cornerstone of Southern society. Stephens was unapologetic in his support for the institution, viewing it as both morally justifiable and economically necessary. His infamous "Cornerstone Speech" in 1861 explicitly stated that the Confederacy was founded on the principle of white supremacy and the belief in the inferiority of Black people. While this stance is abhorrent by modern standards, it was a central policy he championed within the Democratic Party, aligning with the party’s pro-slavery faction.

Stephens also played a pivotal role in the secession movement, using his political influence to rally Southern states to leave the Union. His efforts were instrumental in Georgia’s secession and in uniting the South under a common cause. As a party leader, he worked tirelessly to ensure that the Democratic Party in the South remained committed to secession, even as the national party fractured over the issue. His actions during this period highlight his ability to mobilize political support for a cause he deemed critical to Southern survival.

Finally, Stephens’ post-war reconciliation efforts demonstrate a shift in his party contributions. After the Civil War, he advocated for leniency toward the South and worked to reintegrate Southern states into the Union. As a Congressman during Reconstruction, he pushed for policies that would restore Southern political power while also urging his fellow Democrats to accept the abolition of slavery. This pragmatic approach, though controversial, reflected his commitment to rebuilding the South within the framework of the Democratic Party.

In summary, Alexander H. Stephens’ contributions to the Democratic Party were shaped by his unwavering dedication to states' rights, his defense of slavery, his leadership in the secession movement, and his later efforts at reconciliation. These actions, while deeply tied to the historical context of his time, left an indelible mark on both the party and the nation.

Exploring Diverse Political Party Types and Their Ideologies Worldwide

You may want to see also

Later Political Shifts: Stephens' final party affiliation before retirement or death

Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States of America, underwent significant political shifts throughout his career, particularly in his later years. Initially a staunch Democrat, Stephens’ allegiance to the party began to waver during the tumultuous period leading up to the Civil War. His role in the Confederacy marked a clear departure from the national Democratic Party, aligning instead with the secessionist cause. However, it is his post-war political trajectory that reveals his final party affiliation before his death in 1883.

After the Civil War, Stephens re-entered politics in Georgia, seeking to reconcile his past with the new political landscape. He initially resisted joining the Republican Party, despite its dominance in the Reconstruction South, due to his lingering ties to Democratic principles. Instead, Stephens became a vocal advocate for the rights of Southern states and the reintegration of former Confederates into national politics. This stance positioned him as a bridge between the old and new South, though it did not immediately clarify his party loyalty.

By the late 1870s, Stephens formally rejoined the Democratic Party, a move driven by his opposition to Radical Republican policies and his desire to restore Southern political autonomy. His return to the Democrats was not without controversy, as he had to navigate the party’s evolving platform, which now included elements of populism and reconciliation. Stephens’ final years in politics were marked by his efforts to shape the Democratic Party’s stance on issues like states’ rights and economic policy, reflecting his enduring commitment to Southern interests.

Stephens’ decision to align with the Democrats in his later years was both pragmatic and ideological. Pragmatically, the Democratic Party offered the best platform for advancing his political goals in a post-Reconstruction South. Ideologically, he remained steadfast in his belief in limited federal government and Southern self-determination, principles that resonated with the Democratic Party of the time. This alignment ensured that his legacy would be tied to the party he had long identified with, even as it evolved in response to the nation’s changing dynamics.

In conclusion, Alexander Stephens’ final party affiliation before his death was with the Democratic Party, a return to his political roots after years of secessionist and independent advocacy. This shift underscores the complexities of post-Civil War politics and Stephens’ enduring influence on Southern political thought. His journey from Confederate leader to Democratic statesman highlights the fluidity of political allegiances during this transformative era in American history.

Switching Political Parties in South Dakota: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Stephens, referring to Alexander H. Stephens, belonged to the Democratic Party.

No, Alexander H. Stephens remained a member of the Democratic Party throughout his political career.

No, Stephens was not affiliated with the Whig Party; he was consistently a Democrat.

No, Stephens opposed the Republican Party and its policies, particularly those of Abraham Lincoln.

No, Stephens did not align with any third-party movements and remained loyal to the Democratic Party.