In 1921, Mao Zedong joined the Communist Party of China (CPC) during its founding congress in Shanghai. This pivotal moment marked the beginning of Mao's deep involvement in revolutionary politics and his eventual rise as a central figure in Chinese history. Influenced by Marxist-Leninist ideology and inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, Mao saw the CPC as the vehicle to overthrow imperialist and feudal systems in China and establish a socialist state. His membership in the party laid the foundation for his leadership in the Long March, the Chinese Civil War, and ultimately the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Political Influences: Mao's exposure to revolutionary ideas and Marxist literature before 1921

- Founding of the CCP: The establishment of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai, July 1921

- Mao's Role in 1921: His participation as a delegate during the CCP's first congress

- Collaboration with Comintern: Soviet influence and support in the CCP's early formation

- Ideological Alignment: Mao's commitment to Marxism-Leninism and revolutionary goals of the CCP

Early Political Influences: Mao's exposure to revolutionary ideas and Marxist literature before 1921

Mao Zedong's journey toward joining the Communist Party of China in 1921 was deeply rooted in his early exposure to revolutionary ideas and Marxist literature. Growing up in a rural, agrarian society during the late Qing Dynasty, Mao witnessed firsthand the exploitation of peasants by landlords and the corruption of the ruling class. These experiences sowed the seeds of discontent and a desire for radical change. By the time he arrived in Beijing in 1918, Mao was already immersed in intellectual circles that critiqued traditional Chinese society and sought new paths for national rejuvenation.

One of the pivotal moments in Mao's early political awakening was his encounter with Marxist literature. During his time as a librarian at Peking University, Mao gained access to translations of Marxist texts, including works by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin. These writings offered a framework for understanding class struggle and the inevitability of proletarian revolution. Mao was particularly drawn to Lenin's *Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism*, which analyzed the global exploitation of colonies and semi-colonies. This exposure to Marxist theory provided Mao with a lens through which to interpret China's own struggles against imperialism and feudalism.

Mao's intellectual development was also shaped by his engagement with the New Culture Movement, which emerged in the 1910s as a response to China's humiliating defeats in the Opium Wars and the failure of the 1911 Revolution. Advocates of this movement, such as Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, called for a rejection of Confucian traditions and the adoption of Western science and democracy. Mao, however, went further, arguing that mere cultural reform was insufficient without addressing the economic and political structures that perpetuated inequality. His essay *A Study of Physical Education*, published in 1917, reflected his growing belief in the power of collective action and the need for a revolutionary approach to societal transformation.

Practical exposure to labor activism further solidified Mao's revolutionary convictions. In 1919, he participated in the May Fourth Movement, a nationwide protest against the Treaty of Versailles, which ceded Chinese territories to Japan. This experience taught Mao the importance of mobilizing the masses and the potential of grassroots movements to challenge authority. Simultaneously, his observations of worker strikes in Hunan and Beijing convinced him that the working class and peasantry, not the bourgeoisie, were the true agents of revolutionary change.

By 1921, Mao's intellectual and practical experiences had converged to make him a committed revolutionary. His exposure to Marxist literature, engagement with progressive intellectual movements, and firsthand observations of class struggle prepared him to embrace the Communist Party of China as the vehicle for achieving his vision of a just and egalitarian society. This foundation not only shaped his decision to join the party but also influenced his later adaptations of Marxist theory to the Chinese context, ultimately defining his role as a revolutionary leader.

To trace Mao's early political influences is to understand the interplay between personal experience, intellectual curiosity, and historical context. For those studying revolutionary movements, Mao's pre-1921 journey offers a blueprint for how ideas can evolve into action. It underscores the importance of accessing transformative literature, engaging with progressive movements, and grounding theory in practical realities—lessons that remain relevant for anyone seeking to drive societal change.

Political Parties: Essential Pillars or Hindrances to American Democracy?

You may want to see also

Founding of the CCP: The establishment of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai, July 1921

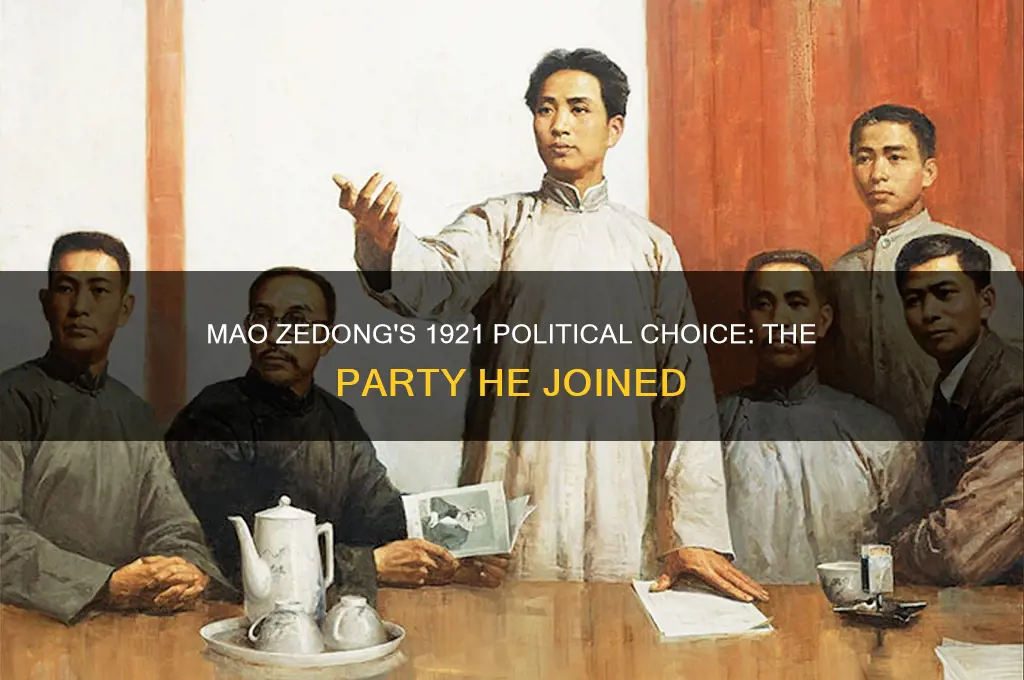

In July 1921, a clandestine meeting in Shanghai marked the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a pivotal moment in modern Chinese history. Among the dozen attendees was Mao Zedong, a young revolutionary who would later become the party’s most iconic leader. This gathering, held in the French Concession to evade detection by the warlord-controlled government, was a response to the failures of the Republican Revolution and the growing influence of Marxist ideas in China. The CCP’s establishment was not merely a political event but a turning point that reshaped the nation’s trajectory, setting the stage for Mao’s eventual rise and the party’s enduring dominance.

The founding of the CCP was a product of its time, influenced by global and domestic forces. The Russian Revolution of 1917 had inspired Chinese intellectuals, including Mao, to explore Marxism as a solution to China’s social and economic crises. Meanwhile, the May Fourth Movement of 1919, a student-led protest against imperialism and feudalism, had radicalized a generation of young Chinese thinkers. Mao, who had worked as a librarian and teacher, was drawn to these ideas, seeing them as tools to challenge the inequalities and foreign domination plaguing China. His decision to join the CCP in 1921 was not just a personal choice but a strategic alignment with a movement he believed could transform his nation.

The Shanghai meeting itself was a study in secrecy and determination. Held in a nondescript house on South Chengdu Road, it brought together representatives from various communist groups across China. Chen Duxiu, a prominent intellectual, was elected the party’s first leader, while Mao represented the Changsha group. Despite its modest beginnings—with only 50 members nationwide—the CCP quickly gained traction by focusing on labor rights, agrarian reform, and anti-imperialist struggles. Mao’s early contributions, particularly his analysis of the peasant class as a revolutionary force, laid the groundwork for the party’s future strategies.

The CCP’s founding also reflected a pragmatic alliance with the Nationalist Party (KMT) under Sun Yat-sen, facilitated by the Comintern. This united front aimed to consolidate power against warlords and foreign interests. However, this partnership was fraught with tension, culminating in the violent split of 1927. Mao’s experience during this period, including his leadership in the Autumn Harvest Uprising, solidified his belief in rural-based revolution, a doctrine that would later define the CCP’s Long March and eventual victory in 1949.

In retrospect, the establishment of the CCP in 1921 was more than just the creation of a political party; it was the birth of a movement that would redefine China’s identity. Mao’s decision to join this fledgling organization was a gamble on a radical vision of societal transformation. From its humble origins in a Shanghai backroom, the CCP grew into a force capable of overthrowing dynasties and reshaping global geopolitics. Understanding this moment is key to grasping not only Mao’s legacy but also the enduring resilience of the party he helped build.

Samoa's Political Incorrectness: Unraveling Cultural Misunderstandings and Stereotypes

You may want to see also

Mao's Role in 1921: His participation as a delegate during the CCP's first congress

In 1921, Mao Zedong joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during its first congress, marking a pivotal moment in both his life and the history of China. As one of the 13 delegates present, Mao’s role was not that of a dominant leader but rather a participant in the formative stages of a movement that would later reshape the nation. Held in secrecy in Shanghai and later moved to a boat on South Lake in Jiaxing due to security concerns, the congress laid the groundwork for the CCP’s ideology and structure. Mao’s presence at this event underscores his early commitment to Marxist-Leninist principles and his growing influence within revolutionary circles.

Mao’s participation as a delegate was shaped by his background as a teacher, librarian, and self-educated Marxist theorist. Unlike some of his contemporaries, who had studied abroad or held prominent positions, Mao brought a unique perspective rooted in his experiences with rural China. His understanding of the peasantry’s struggles would later become central to the CCP’s strategy, but in 1921, he was still refining his ideas. During the congress, Mao listened, debated, and contributed to discussions on the party’s platform, which focused on anti-imperialism, land reform, and worker-peasant alliances. His ability to synthesize theory with practical realities began to set him apart, even if his leadership was not yet fully realized.

The first congress was a modest affair, with limited resources and a small group of attendees, but its significance cannot be overstated. Mao’s role as a delegate was a stepping stone to his eventual rise as the CCP’s chairman and China’s paramount leader. It was here that he first engaged with key figures like Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, who were instrumental in the party’s early development. Mao’s participation also highlights the CCP’s initial focus on urban workers, a strategy he would later challenge by emphasizing the revolutionary potential of the rural masses. This shift in perspective, born from his early involvement, would redefine the party’s trajectory.

To understand Mao’s role in 1921, it’s essential to recognize the context of the time. China was in turmoil, grappling with foreign imperialism, warlordism, and social inequality. The CCP’s first congress was a bold attempt to address these issues through revolutionary means. Mao’s presence as a delegate reflects his early alignment with these goals, even if his methods and priorities evolved over time. His contributions during the congress were not groundbreaking, but they laid the foundation for his future leadership. For historians and analysts, this moment serves as a reminder that even the most influential leaders begin as participants in larger movements.

In practical terms, Mao’s involvement in the 1921 congress offers a lesson in the importance of grassroots engagement and ideological clarity. His ability to connect with the party’s core principles while adapting them to China’s unique circumstances was a key factor in his later success. For those studying political movements or seeking to drive change, Mao’s early role underscores the value of being present, observant, and willing to contribute, even in seemingly insignificant ways. The first congress was not just a historical event but a blueprint for how small beginnings can lead to monumental transformations.

Exploring Unique and Creative Political Party Names Worldwide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Collaboration with Comintern: Soviet influence and support in the CCP's early formation

In 1921, Mao Zedong joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which was founded during the same year. This pivotal moment in Mao’s political career coincided with the CCP’s early collaboration with the Comintern (Communist International), an organization established by the Soviet Union to promote global communist revolution. The Comintern’s influence was instrumental in shaping the CCP’s ideological framework, organizational structure, and strategic direction during its formative years.

The Comintern’s role in the CCP’s early formation was both directive and supportive. Soviet advisors, such as Mikhail Borodin, were dispatched to China to guide the fledgling party. Borodin, for instance, played a critical role in organizing the First United Front between the CCP and the Kuomintang (KMT) in 1923, a strategy aimed at uniting revolutionary forces against warlordism and imperialism. This collaboration was a direct result of Comintern directives, which emphasized the importance of alliances with nationalist movements in semi-colonial countries. The Soviets provided not only ideological guidance but also financial and material support, including funds, weapons, and training for CCP cadres.

However, the Soviet influence was not without tensions and contradictions. The Comintern’s directives often clashed with the CCP’s local realities, particularly in rural China, where Mao Zedong would later develop his theory of rural-based revolution. For example, the Comintern initially prioritized urban proletarian revolution, a strategy that proved ineffective in China’s agrarian society. Mao’s eventual shift to rural guerrilla warfare and his critique of urban-centric strategies marked a divergence from Soviet orthodoxy, though the foundational support from the Comintern remained crucial in the CCP’s early survival and growth.

A comparative analysis of the Comintern’s role in other communist movements highlights its unique impact on the CCP. Unlike in Europe, where communist parties often faced repression and isolation, the CCP benefited from the Comintern’s ability to leverage the KMT alliance, which provided a temporary shield and resources. This pragmatic approach, though later abandoned, underscores the adaptability of Soviet support in different national contexts. The CCP’s ability to eventually chart its own course, independent of Soviet dictates, was rooted in the early lessons learned from this collaboration.

In practical terms, the Comintern’s support was a double-edged sword. While it provided the CCP with essential tools for survival, it also created dependencies and ideological rigidities that the party had to overcome. For instance, the Comintern’s insistence on strict adherence to Marxist-Leninist dogma initially stifled Mao’s innovative thinking. Yet, it was this very foundation that allowed Mao to later reinterpret Marxism-Leninism to suit China’s unique conditions, ultimately leading to the CCP’s rise as a dominant political force. The collaboration with the Comintern, therefore, serves as a critical case study in the interplay between external support and indigenous adaptation in revolutionary movements.

Interest Groups and Political Parties: Latest Developments Shaping Today’s Politics

You may want to see also

Ideological Alignment: Mao's commitment to Marxism-Leninism and revolutionary goals of the CCP

Mao Zedong's decision to join the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921 was not merely a political choice but a profound ideological commitment. At the time, China was in turmoil, grappling with imperialist encroachment, warlordism, and social inequality. Mao, already a fervent believer in the transformative power of revolution, found in Marxism-Leninism a framework that resonated with his vision for China’s future. This alignment was not coincidental; it was rooted in Mao’s deep study of Marxist theory and his conviction that it offered the only viable path to liberate China’s masses from oppression.

The CCP, founded in 1921, was explicitly Marxist-Leninist in its orientation, advocating for a proletarian revolution to overthrow the bourgeoisie and establish a socialist state. Mao’s commitment to these principles was evident in his early writings and activism. He saw Marxism-Leninism not as a foreign import but as a universal tool adaptable to China’s unique conditions. This adaptability became a hallmark of Mao’s thought, as he later developed the theory of "New Democracy," which tailored Marxist-Leninist principles to China’s semi-colonial, semi-feudal context. His ability to synthesize theory with practice ensured that his ideological alignment with the CCP was both strategic and sincere.

Mao’s dedication to the revolutionary goals of the CCP was unwavering, even in the face of immense challenges. During the Long March (1934–1935), for instance, Mao’s leadership and ideological clarity helped the Party survive near-extinction. His emphasis on mobilizing the peasantry, rather than relying solely on the urban proletariat, demonstrated his pragmatic application of Marxism-Leninism. This shift not only expanded the CCP’s base but also solidified Mao’s position as a key theoretician and leader within the Party. His commitment to revolution was not abstract; it was grounded in the lived realities of China’s rural poor.

To understand Mao’s ideological alignment, one must recognize the symbiotic relationship between his personal beliefs and the CCP’s goals. Mao’s interpretation of Marxism-Leninism—often referred to as Mao Zedong Thought—became the guiding ideology of the Party. This included principles such as the mass line, self-reliance, and continuous revolution. These ideas were not deviations from Marxism-Leninism but extensions of it, tailored to China’s specific historical and social conditions. Mao’s ability to innovate within the ideological framework ensured that the CCP remained relevant and revolutionary, even as it navigated the complexities of state-building and international politics.

In practical terms, Mao’s commitment to Marxism-Leninism and the CCP’s revolutionary goals had far-reaching consequences. It shaped policies like land reform, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution, each of which sought to dismantle old power structures and create a new socialist society. While these initiatives had mixed results, they underscored Mao’s unwavering belief in the transformative potential of revolution. For those studying Mao’s legacy, the lesson is clear: ideological alignment is not merely about adherence to theory but about its creative application to real-world challenges. Mao’s example demonstrates that revolution requires both vision and adaptability, a balance he strove to maintain throughout his leadership of the CCP.

Exploring Diverse Careers in Politics: Roles, Responsibilities, and Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mao Zedong joined the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 1921, which was founded during the First National Congress in Shanghai.

Yes, Mao Zedong was one of the founding members of the Communist Party of China in 1921, playing a key role in its establishment.

No, Mao Zedong did not join any other political parties before 1921. His involvement in revolutionary activities led him directly to co-founding the Communist Party of China that year.