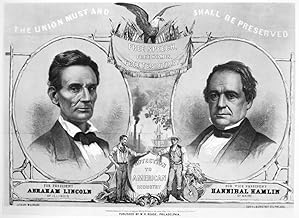

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, was a member of the Republican Party during the 1860 presidential election. At that time, the Republican Party was relatively new, having been founded in the mid-1850s, and it primarily opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Lincoln’s platform emphasized preserving the Union, limiting the spread of slavery, and promoting economic modernization. His nomination and subsequent victory in 1860 marked a significant shift in American politics, as the Republican Party emerged as a dominant force, while the Democratic Party, deeply divided over slavery, failed to unite behind a single candidate. Lincoln’s election was a catalyst for the secession of Southern states, ultimately leading to the Civil War.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Republican Party |

| Founding Year | 1854 |

| Core Principles | Anti-slavery, economic modernization, strong national government |

| Platform in 1860 | Opposed expansion of slavery, supported internal improvements, emphasized national unity |

| Key Figures (1860) | Abraham Lincoln, Hannibal Hamlin, William H. Seward |

| Election Outcome (1860) | Abraham Lincoln elected as President |

| Historical Context | Formed in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the collapse of the Whig Party |

| Regional Support | Strong in the North and West, limited support in the South |

| Symbol | Traditionally associated with the elephant (though not officially adopted until later) |

| Long-term Impact | Became one of the two dominant political parties in the United States |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Lincoln's Early Political Affiliations

Abraham Lincoln's early political affiliations were marked by a series of strategic shifts and evolving ideologies, reflecting both personal growth and the tumultuous political landscape of the 19th century. Beginning his political career in the 1830s, Lincoln initially aligned himself with the Whig Party, a group that championed internal improvements, protective tariffs, and a strong national bank. These early affiliations were pragmatic, as the Whigs offered a platform that resonated with Lincoln's vision for economic development and national unity. His time as a Whig state legislator in Illinois laid the groundwork for his future political ambitions, though the party’s eventual collapse in the 1850s forced him to seek new alliances.

The dissolution of the Whig Party in the mid-1850s left Lincoln politically adrift but not inactive. He briefly associated with the short-lived Know-Nothing Party, though his involvement was minimal and primarily tactical. Lincoln’s true political realignment came with the emergence of the Republican Party in 1854, which opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. This shift was not merely opportunistic but deeply ideological, as Lincoln’s moral opposition to slavery solidified during this period. His famous debates with Stephen A. Douglas in 1858, while unsuccessful in securing him a Senate seat, cemented his position as a leading voice against the spread of slavery and a key figure within the Republican Party.

By 1860, Lincoln’s political affiliations had crystallized around the Republican Party, which nominated him as its presidential candidate. His platform emphasized preserving the Union, restricting the expansion of slavery, and promoting economic modernization. Lincoln’s ability to navigate the complexities of his earlier affiliations—from Whig to Republican—demonstrated his political acumen and adaptability. This evolution was not just a matter of party labels but a reflection of his deepening commitment to principles that would define his presidency.

Understanding Lincoln’s early political affiliations requires recognizing the fluidity of 19th-century American politics. His journey from Whig to Republican was not linear but shaped by the issues of his time, particularly the moral and political crisis of slavery. This trajectory highlights the importance of context in political identity, as Lincoln’s affiliations were less about party loyalty and more about advancing a vision for the nation’s future. For those studying political history, Lincoln’s early career offers a case study in how personal convictions and external circumstances can shape a leader’s path.

Practical takeaways from Lincoln’s early affiliations include the value of adaptability in politics and the importance of aligning with platforms that reflect one’s core values. Aspiring politicians can learn from Lincoln’s strategic shifts, which were guided by principle rather than expediency. Additionally, his ability to rise from local politics to the national stage underscores the significance of building a strong foundation in regional leadership. By examining Lincoln’s early career, one gains insight into the interplay between personal growth, ideological commitment, and political strategy—elements that remain relevant in today’s dynamic political landscape.

Which Political Party Did Former President George W. Bush Belong To?

You may want to see also

Formation of the Republican Party

The Republican Party, to which Abraham Lincoln belonged in 1860, emerged as a response to the moral and political crises of the mid-19th century. Formed in 1854, the party coalesced around opposition to the expansion of slavery into new territories, a stance that distinguished it from the Whig and Democratic Parties. This anti-slavery platform was not merely a political tactic but a reflection of the growing moral outrage among Northerners, who saw slavery as incompatible with the nation’s founding principles of liberty and equality. The party’s formation was a direct reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed slavery to spread based on popular sovereignty. This act galvanized anti-slavery activists, who saw it as a dangerous concession to the Slave Power.

The Republican Party’s rise was swift and strategic. It drew support from former Whigs, Free Soil Democrats, and abolitionists, creating a coalition united by a common goal: halting the westward expansion of slavery. The party’s early leaders, such as William Seward and Salmon Chase, were vocal critics of slavery, but they also recognized the need to appeal to a broader electorate. By framing the issue as one of preserving the Union and protecting free labor, the Republicans managed to attract moderate voters who might not have supported outright abolition. This pragmatic approach allowed the party to grow rapidly, winning control of the House of Representatives in 1856 and setting the stage for Lincoln’s presidential victory in 1860.

Lincoln’s affiliation with the Republican Party was pivotal in his political ascent. Though he was not among the party’s founders, his moderate views on slavery and his reputation as a skilled debater made him an ideal candidate. His 1858 debates with Stephen A. Douglas brought national attention to the slavery issue, and his argument that the nation could not endure permanently half-slave and half-free resonated with many voters. By 1860, the Republican Party had become the dominant political force in the North, and Lincoln’s nomination as its presidential candidate was a testament to the party’s ability to unite diverse factions under a single banner.

The formation of the Republican Party was not without challenges. Internal divisions over the extent and timing of anti-slavery measures threatened to fracture the party. Radical Republicans pushed for immediate and aggressive action against slavery, while moderates like Lincoln favored a more gradual approach. Additionally, the party faced fierce opposition from Southern Democrats, who viewed Republican policies as a direct threat to their way of life. Despite these obstacles, the party’s focus on preventing the spread of slavery provided a clear and compelling message that resonated with Northern voters. This unity of purpose was crucial in securing Lincoln’s election and setting the stage for the Civil War.

In retrospect, the formation of the Republican Party was a transformative moment in American political history. It redefined the nation’s political landscape by placing the issue of slavery at the forefront of public debate. The party’s success in 1860 was not just a victory for Lincoln but a validation of its anti-slavery platform. By uniting disparate groups under a common cause, the Republicans demonstrated the power of moral conviction in shaping political movements. Their legacy endures not only in the abolition of slavery but also in the enduring principles of equality and justice that continue to guide the nation.

Unlocking Power Dynamics: Why Study Politics at University?

You may want to see also

1860 Republican Platform

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected as the first Republican President of the United States, a party that had only been established a few years prior. The 1860 Republican Platform was a pivotal document that outlined the party's principles and policies, which would shape the nation's future. This platform was a direct response to the growing tensions between the North and the South, primarily over the issue of slavery.

The Core Principles: A United Stance Against Slavery Expansion

The Republican Party's 1860 platform was unequivocal in its opposition to the expansion of slavery into the western territories. This stance was not merely a moral objection but a strategic move to prevent the South from gaining more political power in Congress. The platform stated, "That the normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom; that as our Republican fathers...held it to be, so we hold it now to be, a sacred duty to prevent its overthrow." This principle was the cornerstone of the party's appeal to Northern voters, who feared the economic and political dominance of the slave-holding South.

Economic Policies: Fostering Growth and Opportunity

Beyond the slavery issue, the 1860 Republican Platform proposed a series of economic measures aimed at promoting national growth and individual prosperity. The party advocated for a protective tariff to encourage domestic manufacturing, a policy that resonated with Northern industrialists. Additionally, the platform supported internal improvements, such as the construction of railroads and canals, to facilitate commerce and communication across the vast American landscape. These economic policies were designed to create a strong, unified nation where opportunity was accessible to all, regardless of birth or status.

Comparative Analysis: Contrasting with the Democratic Platform

A comparative look at the 1860 Democratic Platform reveals stark differences in priorities and values. While the Republicans focused on containing slavery and fostering economic growth, the Democrats emphasized states' rights and the preservation of the Union through compromise on the slavery issue. The Democratic platform's support for the Dred Scott decision and its opposition to federal intervention in territorial slavery laws stood in sharp contrast to the Republican stance. This divergence highlights the deep ideological divide that characterized American politics in the lead-up to the Civil War.

Practical Implications: The Impact on Lincoln's Presidency

The 1860 Republican Platform not only guided Lincoln's campaign but also influenced his presidential policies. Lincoln's commitment to preventing the expansion of slavery, as outlined in the platform, was a key factor in the secession of Southern states and the outbreak of the Civil War. His administration's economic policies, including the Morrill Tariff and the Pacific Railroad Acts, were direct implementations of the platform's promises. Understanding this platform provides crucial insights into the motivations and actions of Lincoln's presidency, offering a lens through which to analyze the complexities of the Civil War era.

A Lasting Legacy: Shaping Modern American Politics

The 1860 Republican Platform's emphasis on freedom, economic opportunity, and national unity continues to resonate in American politics. While the specific issues have evolved, the underlying principles of the platform—opposition to the expansion of oppressive systems and the promotion of economic growth—remain relevant. For instance, modern debates on immigration, economic policy, and social justice often echo the themes first articulated in this historic document. By studying the 1860 Republican Platform, we gain not only a deeper understanding of the past but also valuable perspectives on contemporary political challenges.

How Political Parties Are Damaging American Politics: 5 Key Examples

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lincoln's Nomination Process

Abraham Lincoln's nomination as the Republican Party candidate in 1860 was a pivotal moment in American political history, shaped by strategic maneuvering, regional tensions, and the fracturing of the Democratic Party. The process began at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, where Lincoln, a relatively lesser-known figure on the national stage, emerged as a compromise candidate. His nomination was not the result of personal charisma or a dominant political machine but rather a calculated decision by party leaders to unite behind a candidate who could appeal to both the moderate and radical factions of the party.

The nomination process was a masterclass in political strategy. Lincoln's campaign team, led by figures like David Davis and Leonard Swett, worked behind the scenes to position him as a viable candidate. They emphasized his moderate views on slavery, his strong stance on preserving the Union, and his humble background as a self-made man from Illinois. This narrative resonated with delegates, particularly those from the Midwest, who saw Lincoln as a candidate who could bridge the growing divide between the North and South. His famous "House Divided" speech, though delivered in 1858, continued to influence perceptions of his ability to address the nation's most pressing issue.

One of the key factors in Lincoln's nomination was the fragmentation of the Democratic Party. The Democrats, unable to agree on a single candidate, split into Northern and Southern factions, each nominating their own candidate. This division effectively handed the electoral advantage to the Republicans, who, despite being a relatively new party, presented a united front. Lincoln's nomination was further bolstered by the absence of a strong contender from the Whig Party, which had collapsed by 1860, leaving many former Whigs to align with the Republicans.

The convention itself was a tense affair, with multiple ballots required to secure Lincoln's nomination. His primary rivals included William H. Seward, the frontrunner and a prominent figure in the Republican Party, and Salmon P. Chase, a radical abolitionist. Lincoln's team strategically highlighted Seward's perceived radicalism and Chase's lack of broad appeal, positioning Lincoln as the safe choice. On the third ballot, Lincoln secured the nomination, a testament to the effectiveness of his campaign's behind-the-scenes efforts.

The Donkey's Political Party: Unraveling the Democratic Symbol's History

You may want to see also

Whigs to Republicans Transition

The Whig Party, once a dominant force in American politics, began to fracture in the 1850s over the issue of slavery. This internal division created a vacuum that the newly formed Republican Party was quick to fill. Abraham Lincoln, a prominent Whig leader in Illinois, found himself at the crossroads of this political transformation. By 1860, the Whigs were all but defunct, and Lincoln had emerged as a leading figure in the Republican Party, which had coalesced around the platform of preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories.

To understand Lincoln's transition from Whig to Republican, consider the ideological evolution of the time. The Whigs had traditionally focused on economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong federal government. However, their inability to address the moral and political crisis of slavery led to their demise. The Republicans, on the other hand, seized on the anti-slavery sentiment, particularly in the North, and framed their agenda around preserving the Union and limiting the spread of slavery. Lincoln's own views aligned closely with this new party, as he had long opposed the expansion of slavery, though he was not an abolitionist in the radical sense.

A key moment in this transition was the 1858 Senate race between Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. Their debates highlighted the growing divide over slavery and foreshadowed the realignment of political parties. While Lincoln lost the Senate seat, his articulate defense of the principles that would later define the Republican Party elevated his national profile. By 1860, he was the ideal candidate to unite the diverse factions within the Republican Party, from moderate Whigs to anti-slavery Democrats.

Practical lessons from this transition include the importance of adaptability in politics. Lincoln's shift from Whig to Republican was not merely a change of party label but a strategic realignment with the prevailing moral and political currents of his time. For modern political figures, this underscores the need to listen to the evolving concerns of constituents and to be willing to break from outdated party structures when necessary. Lincoln's success in 1860 demonstrates that principled leadership, combined with political pragmatism, can bridge divides and forge new coalitions.

Finally, the Whigs-to-Republicans transition illustrates the cyclical nature of political parties. Parties rise and fall based on their ability to address the pressing issues of their era. The Republican Party's emergence as the dominant force in the North was not inevitable but was the result of clear messaging, strategic organization, and the ability to attract leaders like Lincoln. This historical example serves as a reminder that political institutions must continually reinvent themselves to remain relevant, a lesson as applicable today as it was in the mid-19th century.

Switching Political Parties in Alabama: A Step-by-Step Voter's Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Abraham Lincoln belonged to the Republican Party in 1860.

Abraham Lincoln was a Republican during the 1860 election.

Yes, Lincoln was previously a member of the Whig Party but joined the Republican Party after the Whigs disbanded in the 1850s.

The Republican Party in 1860 opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, promoted internal improvements, and supported tariffs to protect American industry.

Lincoln’s Republican Party affiliation helped him win the presidency by uniting Northern voters against the divided Democratic Party and the Constitutional Union Party.