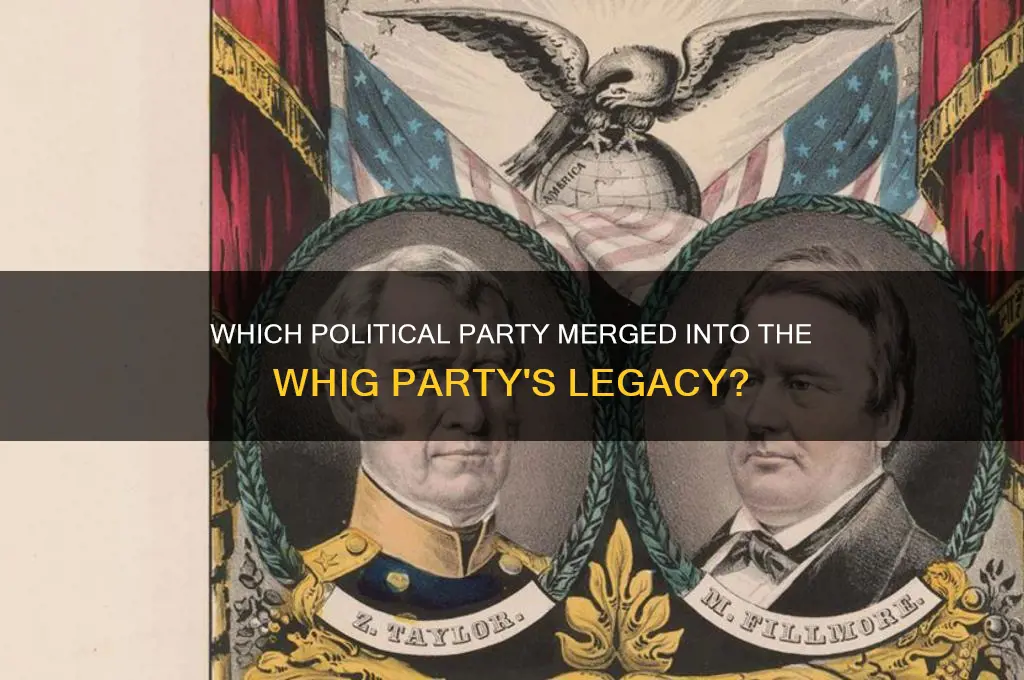

The Whig Party, a dominant force in American politics during the mid-19th century, emerged as a coalition of diverse factions opposed to the policies of Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party. Among the groups that contributed to its formation, the National Republican Party, led by figures like Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, played a pivotal role. This party, which had previously opposed Jackson’s policies, merged with other anti-Jackson factions, including disaffected Democrats and members of the short-lived Anti-Masonic Party, to create the Whig Party in the early 1830s. The National Republicans, with their emphasis on economic modernization and internal improvements, became a cornerstone of the Whig Party’s platform, shaping its identity as a party advocating for national development and limited executive power.

Explore related products

$48.99 $55

What You'll Learn

- Democratic-Republican Party: Many Democratic-Republicans joined Whigs, opposing Andrew Jackson's policies and centralization

- National Republicans: Led by Henry Clay, they merged into Whigs, advocating for economic modernization

- Anti-Masonic Party: Some Anti-Masons joined Whigs, sharing concerns over Jacksonian democracy and secrecy

- Nullifier Party: Southern Nullifiers aligned with Whigs to resist federal tariffs and central authority

- Conservative Democrats: Disillusioned Democrats joined Whigs, favoring limited government and economic conservatism

Democratic-Republican Party: Many Democratic-Republicans joined Whigs, opposing Andrew Jackson's policies and centralization

The Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, dominated American politics in the early 19th century. However, by the 1830s, internal divisions and external pressures led many of its members to seek a new political home. The rise of Andrew Jackson and his policies of centralization, particularly his aggressive approach to Native American removal and his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States, alienated a significant faction within the party. These dissenters, often referred to as the "Old Republicans," found common cause with other anti-Jackson groups, ultimately coalescing into the Whig Party.

To understand this transition, consider the ideological clash between Jacksonian Democracy and the principles of the Old Republicans. While Jackson championed the common man and states' rights, his critics feared his policies undermined constitutional checks and balances. For instance, Jackson’s veto of the Maysville Road Bill in 1830, which he deemed unconstitutional, highlighted his strict constructionist views. This move, along with his dismantling of the national bank, convinced many Democratic-Republicans that Jackson’s centralizing tendencies threatened individual liberties and economic stability. These concerns became a rallying cry for those who would later join the Whigs.

The formation of the Whig Party was not merely a reaction to Jackson’s policies but also a strategic realignment. The Whigs drew from diverse groups, including former Federalists, disaffected Democratic-Republicans, and emerging industrialists. For the Old Republicans, the Whig Party offered a platform to oppose Jackson’s executive overreach and promote internal improvements, such as roads and canals, which they believed were essential for national growth. This coalition was pragmatic, uniting disparate factions under a common banner of resistance to Jacksonian Democracy.

A practical takeaway from this historical shift is the importance of adaptability in political movements. The Democratic-Republicans who joined the Whigs recognized that their principles could not thrive within their original party structure. By aligning with the Whigs, they preserved their opposition to centralization and executive power, even as the political landscape evolved. This example underscores the necessity of strategic realignment when core values are threatened by internal or external forces.

In conclusion, the migration of Democratic-Republicans to the Whig Party was a pivotal moment in American political history. It demonstrated how ideological disagreements, particularly over centralization and executive authority, can reshape party dynamics. For modern observers, this episode serves as a reminder that political parties are not static entities but fluid coalitions capable of transformation in response to changing circumstances and leadership.

Brexit Perspectives: How UK Political Parties View Britain's EU Exit

You may want to see also

National Republicans: Led by Henry Clay, they merged into Whigs, advocating for economic modernization

The National Republicans, a pivotal faction in early 19th-century American politics, emerged as a response to the perceived failures of the Democratic Party under Andrew Jackson. Led by the charismatic and visionary Henry Clay, this group championed a platform centered on economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong federal role in fostering national growth. Their merger into the Whig Party marked a strategic realignment that reshaped the political landscape, offering a compelling alternative to Jacksonian democracy.

At the heart of the National Republicans’ agenda was the American System, a tripartite economic plan devised by Clay. This system emphasized protective tariffs to nurture domestic industries, a national bank to stabilize the economy, and federally funded infrastructure projects to connect the nation. These policies were not merely economic strategies but a vision for a unified, industrially advanced America. By advocating for such measures, the National Republicans positioned themselves as the party of progress, appealing to merchants, manufacturers, and forward-thinking farmers who saw the potential of a modernized economy.

The merger into the Whig Party was neither abrupt nor accidental. It was a calculated move to consolidate opposition to Jackson’s policies, particularly his dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States and his laissez-faire approach to economic regulation. The Whigs, inheriting the National Republicans’ platform, became the champions of active federal intervention in economic affairs. This fusion allowed the party to present a cohesive front against the Democrats, rallying diverse interests under a common banner of national development and economic prosperity.

Henry Clay’s leadership was instrumental in this transformation. Known as the “Great Compromiser,” Clay’s ability to bridge ideological divides and forge alliances was critical in uniting disparate factions into the Whig Party. His vision of a federally supported economy resonated with Northern industrialists and Western pioneers alike, creating a broad coalition that challenged Democratic dominance. Clay’s influence extended beyond policy; his political acumen and moral authority made him the de facto leader of the Whigs, even when he was not their presidential candidate.

The legacy of the National Republicans within the Whig Party is evident in their enduring impact on American political ideology. Their emphasis on economic modernization laid the groundwork for future Republican Party policies and shaped the nation’s approach to industrialization. While the Whigs ultimately disbanded in the 1850s, the principles championed by Clay and his allies—federal investment in infrastructure, protectionism, and a strong national bank—continued to influence American politics. The National Republicans’ merger into the Whigs was not just a tactical maneuver but a foundational moment in the evolution of American political thought.

Exploring Nations Without Political Parties: Unique Governance Models Worldwide

You may want to see also

Anti-Masonic Party: Some Anti-Masons joined Whigs, sharing concerns over Jacksonian democracy and secrecy

The Anti-Masonic Party, born in the late 1820s, was a political movement fueled by suspicion of Freemasonry's secrecy and influence. While its core focus was opposition to Masonic lodges, Anti-Masons also harbored broader anxieties about Andrew Jackson's democratic reforms. These reforms, characterized by expanded suffrage and a stronger executive branch, struck many Anti-Masons as a threat to traditional Republican virtues and local control. This shared unease with Jacksonian democracy created a natural alliance between some Anti-Masons and the emerging Whig Party.

The Whigs, a diverse coalition united primarily by their opposition to Jackson, found common ground with Anti-Masons in their skepticism of concentrated power and their emphasis on constitutional restraint. Anti-Masons brought to the Whigs a network of supporters, particularly in the Northeast, and a rhetorical framework that critiqued Jackson's populism as dangerous and secretive. This merger wasn't without friction. Some Anti-Masons resisted abandoning their singular focus on Freemasonry, while Whigs were wary of alienating potential voters who might not share the same intensity of anti-Masonic sentiment.

The absorption of Anti-Masonic elements into the Whig Party illustrates a crucial aspect of American political history: the fluidity and adaptability of political movements. Parties are not static entities; they evolve, merge, and dissolve based on shifting ideological currents and strategic calculations. The Anti-Masonic Party's partial integration into the Whigs demonstrates how specific concerns, like opposition to Freemasonry, can become subsumed within broader political narratives, in this case, the Whig critique of Jacksonian democracy.

This historical example offers a valuable lesson for understanding contemporary political alliances. While issues and ideologies may change, the underlying dynamics of coalition-building remain remarkably consistent. Groups with seemingly narrow focuses can find common cause with larger movements when their core anxieties resonate with broader societal concerns.

Understanding SRC: Its Role and Impact in Political Systems Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nullifier Party: Southern Nullifiers aligned with Whigs to resist federal tariffs and central authority

The Nullifier Party, born in the early 1830s, emerged as a fiery response to federal tariffs that strangled the Southern economy. Led by figures like John C. Calhoun, the party championed states’ rights and the doctrine of nullification, arguing that states could invalidate federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. This radical stance, though short-lived, left a lasting imprint on American political history.

To understand their alignment with the Whigs, consider the Nullifiers’ core grievance: the Tariff of 1828, dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations." This federal policy imposed heavy taxes on imported goods, disproportionately harming the agrarian South while benefiting Northern industrialists. The Nullifiers saw this as an overreach of federal authority and a threat to their economic survival. Their alliance with the Whigs, a party traditionally associated with economic modernization and internal improvements, might seem counterintuitive. However, the Whigs’ opposition to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party and their skepticism of unchecked executive power created common ground. Both parties sought to curb what they viewed as federal overreach, even if their ultimate goals diverged.

The Nullifiers’ strategy was twofold: first, to nullify the tariffs through state legislation, and second, to forge alliances that could amplify their resistance. By aligning with the Whigs, they gained a platform in Congress and access to Northern politicians sympathetic to their anti-Jackson stance. This tactical partnership, however, was fragile. The Whigs’ focus on national economic development often clashed with the Nullifiers’ agrarian interests, and their union was more a marriage of convenience than a shared vision.

Practical lessons from this historical alliance are clear: in politics, temporary alliances can be powerful tools for achieving specific goals, even when ideological differences persist. For modern activists or policymakers, this underscores the importance of identifying shared enemies or issues as a basis for collaboration. However, such alliances require careful negotiation and a clear understanding of limits. The Nullifiers’ eventual absorption into the Whig Party highlights both the potential and pitfalls of such strategic alignments.

In retrospect, the Nullifier Party’s alignment with the Whigs was a bold but precarious move. It demonstrated the power of leveraging shared opposition to achieve short-term goals, even if long-term compatibility was lacking. For those navigating today’s polarized political landscape, this historical example serves as a reminder: alliances built on resistance to a common threat can be effective, but they demand clarity, pragmatism, and a willingness to adapt.

Exploring Russia's Political Landscape: Key Parties and Their Influence

You may want to see also

Conservative Democrats: Disillusioned Democrats joined Whigs, favoring limited government and economic conservatism

In the mid-19th century, a significant shift occurred in American politics as disillusioned Democrats, frustrated with their party's direction, sought a new political home. These Conservative Democrats, often from the South and West, found common ground with the Whig Party, particularly in their shared commitment to limited government and economic conservatism. This migration was not merely a reaction to Democratic policies but a deliberate alignment with Whig principles that prioritized fiscal restraint and a smaller federal presence.

The appeal of the Whig Party to these Democrats lay in its pragmatic approach to governance. Whigs advocated for internal improvements, such as infrastructure development, but insisted these be funded and managed at the state level rather than by an overreaching federal government. This stance resonated with Conservative Democrats who feared centralized power and its potential to infringe on states' rights and individual liberties. For instance, Whigs supported tariffs to protect American industries but opposed using federal funds for projects that could be handled locally, a position that mirrored the economic conservatism of these disillusioned Democrats.

A key factor in this political realignment was the Whigs' ability to bridge ideological divides. While the party included diverse factions, its core principles of limited government and economic prudence provided a unifying framework. Conservative Democrats, often skeptical of expansive federal programs, found in the Whigs a party that respected their concerns about government overreach. This convergence was particularly evident in the 1830s and 1840s, when issues like the Second Bank of the United States and federal spending on internal improvements dominated political discourse.

Practical considerations also played a role in this shift. For Conservative Democrats in rural or agrarian regions, the Whigs' emphasis on local control and economic stability offered a more appealing vision for their communities. By joining the Whigs, these Democrats could advocate for policies that directly benefited their constituents without compromising their principles. This strategic alignment was not just ideological but also a means to achieve tangible outcomes in a rapidly changing political landscape.

In conclusion, the migration of Conservative Democrats to the Whig Party was a nuanced and deliberate process, driven by shared values of limited government and economic conservatism. This movement highlights the fluidity of political alliances in the 19th century and the importance of pragmatic, principle-based politics. For modern observers, it serves as a reminder that political parties are not static entities but dynamic coalitions shaped by the evolving priorities of their members. Understanding this historical shift offers valuable insights into the complexities of political realignment and the enduring appeal of conservative principles.

Shifting Beliefs: Can Political Parties Evolve Their Core Ideologies?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The National Republican Party, led by figures like Henry Clay, merged into the Whig Party in the 1830s.

Yes, many members of the Anti-Masonic Party joined the Whig Party in the 1830s, contributing to its formation and early growth.

Yes, several factions of the Democratic-Republican Party, particularly those opposed to Andrew Jackson, coalesced to form the Whig Party in the 1830s.

![By Michael F. Holt - The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics (1999-07-02) [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51TQpKNRjoL._AC_UY218_.jpg)