The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark piece of legislation that outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, was primarily advanced by the Democratic Party under the leadership of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Despite its significance, the bill faced fierce opposition, particularly from conservative Southern Democrats, who filibustered the legislation for 54 days. However, with the support of liberal Democrats and a coalition of Republicans, the act eventually passed, marking a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement. While the Democratic Party played a central role in its passage, it is important to note that the act’s success was also due to bipartisan efforts, as many Republicans, particularly in the Senate, provided crucial support to overcome the filibuster and ensure its enactment.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Democratic Party's Role: Key in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Republican Support: Moderate Republicans backed the Act, ensuring bipartisan passage

- LBJ's Leadership: President Lyndon B. Johnson championed the Act's enactment

- Southern Opposition: Southern Democrats resisted, but were outvoted by northern allies

- Civil Rights Movement: Activism pressured politicians to advance the legislation

Democratic Party's Role: Key in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Democratic Party played a pivotal role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark legislation that outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. This act was a significant milestone in the civil rights movement, and the Democrats' leadership and strategic maneuvering were crucial in its success. Despite facing strong opposition, particularly from Southern Democrats, the party's leadership, including President Lyndon B. Johnson, worked tirelessly to garner support and secure the necessary votes.

To understand the Democratic Party's role, consider the political landscape of the time. The party was divided, with many Southern Democrats opposing civil rights reforms due to concerns over states' rights and racial segregation. However, the national Democratic leadership, recognizing the moral and political imperative of civil rights, took a firm stance in favor of the legislation. President Johnson, a former Senate Majority Leader, used his extensive knowledge of congressional procedures and relationships to build a coalition of supporters. He employed a combination of persuasion, compromise, and strategic deal-making to win over skeptical lawmakers, demonstrating the party's commitment to advancing civil rights.

A critical aspect of the Democratic Party's strategy was its ability to forge alliances across party lines. While the majority of support for the Civil Rights Act came from Democrats, the party also needed Republican votes to overcome the filibuster in the Senate. The Democrats' leadership reached out to moderate Republicans, highlighting the bipartisan nature of the cause and emphasizing the importance of civil rights as a national issue. This collaborative approach not only secured the necessary votes but also set a precedent for future legislative efforts, showcasing the potential for cross-party cooperation on significant social reforms.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act had far-reaching consequences, reshaping American society and politics. For the Democratic Party, it solidified its position as the party of civil rights, attracting support from African American voters and progressive activists. However, it also led to a realignment of political alliances, as many Southern Democrats, disillusioned with the party's stance on civil rights, began to shift their allegiance to the Republican Party. This shift would have long-term implications for the political landscape, influencing electoral strategies and policy priorities for decades to come.

In retrospect, the Democratic Party's role in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a defining moment in American history. It required courage, strategic acumen, and a deep commitment to justice and equality. By championing this legislation, the Democrats not only advanced the cause of civil rights but also demonstrated the power of political leadership in effecting social change. This achievement serves as a reminder of the importance of principled leadership and the potential for legislative action to transform society, offering valuable lessons for contemporary efforts to address ongoing challenges related to racial justice and equality.

Exploring John Paul Stevens' Political Party Affiliation: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Republican Support: Moderate Republicans backed the Act, ensuring bipartisan passage

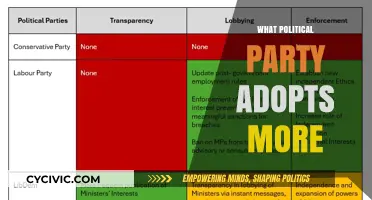

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 stands as a landmark piece of legislation, but its passage was far from guaranteed. While the Democratic Party is often credited with its advancement, the role of moderate Republicans cannot be overstated. These lawmakers played a pivotal role in ensuring the bill’s bipartisan passage, defying party lines and Southern opposition to secure a historic victory for civil rights. Their support was not merely symbolic; it was mathematically essential, as the bill faced a formidable filibuster in the Senate, requiring a two-thirds majority to invoke cloture and bring it to a vote.

To understand the significance of Republican support, consider the numbers. Of the 27 Republican senators who voted for cloture, their collective action was critical in ending the longest filibuster in Senate history at that time. Without their votes, the bill would have been stalled indefinitely. In the House, 138 Republicans joined 152 Democrats to pass the bill, demonstrating a rare instance of bipartisan cooperation on a deeply divisive issue. This coalition was not accidental but the result of strategic alliances between moderate Republicans, led by figures like Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois, and the Johnson administration. Dirksen’s role, in particular, was instrumental; his support lent credibility to the bill and encouraged other Republicans to follow suit.

The motivations of these moderate Republicans were multifaceted. For some, it was a matter of principle, rooted in a belief in equality and justice. Others saw it as a political necessity, recognizing that the Republican Party needed to broaden its appeal beyond its traditional base. The 1964 presidential election loomed large, and the party’s nominee, Barry Goldwater, opposed the bill, creating a rift within the GOP. Moderate Republicans sought to distance themselves from Goldwater’s stance, positioning themselves as the party’s pragmatic wing. This internal party dynamics highlight the complexities of political decision-making, where individual convictions and strategic calculations often intertwine.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between the Republican Party of 1964 and its later iterations. In subsequent decades, the GOP shifted further to the right, and civil rights became a more partisan issue. The moderate Republicans of the 1960s, however, exemplified a different era of politics, one where bipartisanship was not only possible but necessary for progress. Their legacy serves as a reminder of the potential for cross-party collaboration in addressing societal challenges. For those seeking to replicate such achievements today, the lesson is clear: building bridges across party lines requires leadership, compromise, and a shared commitment to the greater good.

In practical terms, the story of moderate Republican support for the Civil Rights Act offers a blueprint for legislative success. It underscores the importance of identifying key allies, leveraging procedural mechanisms like cloture, and framing the issue in a way that appeals to both principle and political expediency. For advocates working on contentious issues today, this historical example provides actionable insights. Engage with moderates in the opposing party, highlight the moral and practical imperatives of the cause, and be prepared to navigate internal party divisions. The passage of the Civil Rights Act was not just a triumph of legislation but a testament to the power of strategic coalition-building.

Wyoming's Party Switching Rules: Can You Change Anytime?

You may want to see also

LBJ's Leadership: President Lyndon B. Johnson championed the Act's enactment

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s leadership in championing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a masterclass in political strategy and moral conviction. Facing a deeply divided Congress, Johnson leveraged his decades of legislative experience to build a coalition that transcended party lines. While the Democratic Party, which he led, was instrumental in advancing the bill, Johnson’s success hinged on his ability to outmaneuver Southern Democrats who staunchly opposed it. By framing civil rights as a moral imperative rather than a partisan issue, he secured Republican support, particularly from leaders like Senator Everett Dirksen, who became a critical ally. This bipartisan approach was unprecedented and demonstrated Johnson’s understanding that progress required bridging ideological divides.

Johnson’s tactics were as bold as they were calculated. He famously declared, “We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights,” during his 1964 State of the Union address, setting the stage for urgent action. Behind the scenes, he employed a combination of persuasion, pressure, and political favors to sway undecided lawmakers. For instance, he reminded senators of their reliance on federal funding for their states, subtly implying consequences for opposition. Simultaneously, he appealed to their sense of history, arguing that supporting the bill would place them on the right side of it. This dual approach—carrot and stick, heart and head—was quintessential Johnson, showcasing his ability to adapt his style to the needs of the moment.

A critical turning point in Johnson’s campaign was his decision to invoke the memory of President John F. Kennedy, whose assassination had left the nation in mourning. By positioning the Civil Rights Act as a fulfillment of Kennedy’s vision, Johnson tapped into a reservoir of national grief and idealism. This emotional appeal resonated deeply, both with the public and with lawmakers who had respected Kennedy. It was a strategic move that elevated the bill from a legislative battle to a moral crusade, making it harder for opponents to justify their resistance without appearing callous or unpatriotic.

Despite his successes, Johnson’s leadership was not without cost. His unwavering commitment to civil rights alienated many Southern Democrats, who felt betrayed by their party’s shift away from states’ rights. This rift would eventually contribute to the realignment of the political landscape, as the “Solid South” began its transition from Democratic to Republican dominance. Yet, Johnson’s willingness to sacrifice short-term political capital for long-term progress remains a testament to his leadership. He understood that true statesmanship often requires making difficult choices, even when they come at a personal or partisan expense.

In retrospect, Johnson’s role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act offers a blueprint for effective leadership in the face of entrenched opposition. His ability to combine moral clarity with political pragmatism, to appeal to both emotion and reason, and to forge unlikely alliances underscores the complexity of his approach. For those seeking to drive meaningful change today, Johnson’s example serves as a reminder that progress often demands courage, creativity, and a willingness to challenge the status quo—even within one’s own party.

Pressure Groups and Political Parties: Allies, Rivals, or Independent Forces?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Southern Opposition: Southern Democrats resisted, but were outvoted by northern allies

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 stands as a monumental piece of legislation, yet its passage was fiercely contested, particularly by Southern Democrats. This resistance was rooted in a deep-seated commitment to maintaining racial segregation and states' rights, principles that had long defined the South's political and social landscape. Despite their staunch opposition, these Southern Democrats were ultimately outvoted by a coalition of Northern Democrats and Republicans, who saw the Act as a necessary step toward racial equality.

To understand the dynamics of this opposition, consider the political climate of the early 1960s. Southern Democrats, often referred to as Dixiecrats, had historically dominated the region's politics, leveraging their power to block federal interventions in racial matters. Their resistance to the Civil Rights Act was not merely symbolic; it involved filibusters, amendments designed to weaken the bill, and public rhetoric that framed the legislation as an assault on Southern culture and autonomy. For instance, Senator Richard Russell of Georgia led a 54-day filibuster, arguing that the Act would impose "federal control over the very heart of our lives."

However, the tide was turning. Northern Democrats, led by President Lyndon B. Johnson, forged an alliance with moderate Republicans to overcome Southern resistance. This coalition was strategic, leveraging the numerical advantage of Northern representatives to secure the Act's passage. The vote breakdown is instructive: in the House, 152 Democrats and 136 Republicans voted in favor, while 91 Democrats and 35 Republicans opposed it. In the Senate, the cloture vote to end the filibuster saw 44 Democrats and 27 Republicans voting yes, compared to 23 Democrats and 6 Republicans voting no. These numbers highlight the critical role of Northern Democrats in countering Southern opposition.

The Southern Democrats' defeat was not just a legislative loss but a symbolic shift in American politics. Their inability to block the Act signaled the waning influence of segregationist politics on the national stage. Yet, their resistance had lasting consequences, contributing to the realignment of the Democratic Party. Many Southern Democrats, disillusioned by their party's support for civil rights, began to shift their allegiance to the Republican Party, a trend that reshaped the political map of the South for decades to come.

For those studying political strategy or legislative history, the passage of the Civil Rights Act offers a practical lesson in coalition-building and the importance of regional alliances. It demonstrates how a determined majority can overcome entrenched opposition, even when that opposition is deeply rooted in cultural and political traditions. By examining this case, one can glean insights into the mechanics of legislative victories and the long-term implications of such triumphs for party dynamics and regional politics.

The Birth of Media Politics: Which President Revolutionized the Game?

You may want to see also

Civil Rights Movement: Activism pressured politicians to advance the legislation

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 stands as a monumental piece of legislation, but its passage was not the result of political goodwill alone. It was the relentless pressure from grassroots activism that forced politicians to act. The Civil Rights Movement, led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., employed nonviolent protests, marches, and boycotts to expose the injustices of segregation and demand change. These actions, often met with violent resistance, captured national attention and made it impossible for lawmakers to ignore the moral imperative for equality.

Consider the Birmingham Campaign of 1963, where images of children being attacked by police dogs and fire hoses shocked the nation. This campaign, organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), aimed to desegregate public spaces in Birmingham, Alabama. The raw brutality displayed against peaceful protesters galvanized public opinion and put immense pressure on President Kennedy to address civil rights. His subsequent support for federal legislation laid the groundwork for what would become the Civil Rights Act.

Activism also operated behind the scenes, with organizations like the NAACP and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) lobbying politicians, organizing voter registration drives, and filing lawsuits to challenge discriminatory laws. These efforts were not always glamorous, but they were essential in building the political momentum needed for legislative change. For instance, the NAACP’s legal strategy, spearheaded by Thurgood Marshall, culminated in the landmark *Brown v. Board of Education* decision, which laid the foundation for the Civil Rights Act by dismantling the "separate but equal" doctrine.

While the Democratic Party is often credited with advancing the Civil Rights Act, it’s crucial to note that this was not a unified effort. Southern Democrats, known as Dixiecrats, fiercely opposed the bill, staging the longest filibuster in Senate history to block its passage. It was the coalition of liberal Democrats and Republicans, particularly under the leadership of President Lyndon B. Johnson, that ultimately secured the Act’s passage. Johnson’s strategic use of political capital and his ability to navigate partisan divides were critical, but without the sustained pressure from activists, the political will to act might never have materialized.

The lesson here is clear: activism is not just a moral outcry; it’s a strategic tool that shapes political agendas. The Civil Rights Movement demonstrated that by disrupting the status quo, holding politicians accountable, and mobilizing public support, ordinary citizens can force even the most reluctant lawmakers to act. This dynamic remains relevant today, as modern movements for racial justice continue to push for systemic change. To advance legislation, activists must remain persistent, strategic, and unapologetic in their demands for equality.

The Great Political Party Swap: A Historical Shift in American Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party played a central role in advancing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, with President Lyndon B. Johnson leading the effort.

Yes, the Republican Party provided significant support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, with a higher percentage of Republicans voting in favor of it compared to Democrats, though Democrats held the majority in Congress.

Some Democrats, particularly those from Southern states, opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 due to their support for segregation and states' rights, leading to a split within the party.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Democrat, used his political influence and legislative skills to push for the passage of the Civil Rights Act, making it a cornerstone of his administration’s agenda.

Yes, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 accelerated a realignment in American politics, with the Democratic Party increasingly becoming associated with civil rights and the Republican Party gaining support in the South due to opposition to federal intervention.