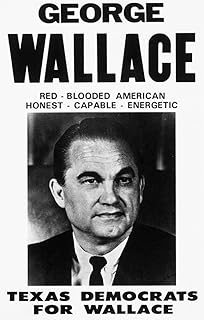

George Wallace, a prominent and controversial figure in American politics, was primarily associated with the Democratic Party during his early political career. However, his political affiliations evolved over time, reflecting his complex and often divisive stances. Initially elected as Governor of Alabama in 1962 as a Democrat, Wallace became a symbol of segregationist policies, famously declaring segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever in his inaugural address. Later, he ran for president multiple times, including as a Democrat in 1964 and 1972, and as an independent in 1968 under the American Independent Party banner. Despite his Democratic roots, Wallace's political legacy is often characterized by his staunch opposition to federal civil rights policies and his appeal to conservative, populist sentiments, which transcended traditional party lines.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | George Wallace was primarily associated with the Democratic Party. |

| Notable Campaigns | Ran for President as a Democrat (1964, 1972, 1976) and as an American Independent Party candidate (1968). |

| Ideology | Known for his segregationist and populist views. |

| Governorship | Served as Governor of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979, 1983–1987) as a Democrat. |

| Stance on Civil Rights | Opposed desegregation and the Civil Rights Movement. |

| Later Political Shift | Moderated his views later in his career, apologizing for his segregationist past. |

| Legacy | Remembered for his role in Southern conservatism and states' rights advocacy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Political Career: Wallace started as a Democrat, initially supporting moderate policies before shifting rightward

- Presidential Campaign: Ran as an independent, advocating segregation and states' rights, winning five Southern states

- American Independent Party: Founded to support Wallace's 1968 campaign, emphasizing anti-establishment and conservative platforms

- Return to Democratic Party: Rejoined Democrats in the 1970s, moderating views and seeking the 1972 and 1976 nominations

- Legacy and Party Affiliation: Wallace's shifting stances reflect complex ties to Democrats, independents, and conservative movements

Early Political Career: Wallace started as a Democrat, initially supporting moderate policies before shifting rightward

George Wallace's early political career is a study in ideological evolution, marked by a notable shift from moderate Democratic policies to a more conservative stance. Initially, Wallace aligned himself with the Democratic Party, a decision that reflected the political landscape of the American South during the mid-20th century. At this stage, his views were characterized by a pragmatic approach to governance, focusing on issues like industrial development and education reform. This period of his career is often overlooked, yet it provides crucial context for understanding his later, more controversial positions.

To grasp Wallace's transformation, consider the political climate of Alabama in the 1950s. As a young state legislator and later as a circuit judge, he supported policies that were, by the standards of the time and place, relatively progressive. For instance, he refused to endorse the "Southern Manifesto," a document opposing racial integration in schools, and even spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan. These early stances were not radical by national standards but were significant within the deeply segregated South. Such positions suggest a politician attuned to the complexities of his constituency, willing to navigate the fine line between reform and tradition.

However, Wallace's political trajectory took a sharp turn during his first gubernatorial campaign in 1958. After losing the Democratic primary to a more segregationist candidate, he famously remarked, "I was out-niggered by John Patterson." This moment marked a turning point, as Wallace began to embrace a more hardline stance on racial issues. His subsequent campaigns would be defined by this shift, leveraging populist rhetoric and appeals to states' rights. This strategic realignment highlights the pragmatic nature of Wallace's early career, where ideological purity took a backseat to political survival and ambition.

The evolution of Wallace's political identity serves as a cautionary tale about the fluidity of political convictions. His initial moderation, while constrained by regional norms, offered a glimpse of a politician capable of nuanced thinking. Yet, the pressures of electoral politics and the allure of power led to a dramatic rightward shift. This transformation underscores the importance of examining politicians' early careers, as they often reveal the seeds of future actions and the compromises made along the way. Understanding Wallace's journey from moderate Democrat to staunch conservative provides valuable insights into the dynamics of political adaptation and the enduring impact of strategic recalibration.

India's Political Landscape: Exploring the Two Dominant Parties

You may want to see also

1968 Presidential Campaign: Ran as an independent, advocating segregation and states' rights, winning five Southern states

George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign stands as a stark example of how regional ideologies can shape national politics. Running as an independent candidate, Wallace championed two controversial pillars: segregation and states' rights. This platform resonated deeply in the South, where he secured victories in five states—Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi—amassing 46 electoral votes. His success wasn't merely a reflection of personal charisma but a symptom of the South's resistance to federal civil rights legislation and the perceived overreach of the federal government. Wallace's campaign exploited racial anxieties and economic grievances, positioning himself as a defender of traditional Southern values against what he framed as Northern liberal encroachment.

Analyzing Wallace's strategy reveals a calculated appeal to a specific demographic. His rhetoric of "states' rights" was a thinly veiled code for opposing federal desegregation efforts, tapping into the fears of white Southerners who felt their way of life was under attack. By running as an independent, Wallace sidestepped the constraints of the major parties, allowing him to present himself as an outsider fighting against the establishment. This positioning was particularly effective in a region already skeptical of federal authority, leveraging historical grievances dating back to Reconstruction. His campaign rallies, often marked by fiery speeches and populist rhetoric, created a sense of unity among his supporters, even as they deepened racial and regional divides.

From a comparative perspective, Wallace's 1968 campaign contrasts sharply with the platforms of his opponents, Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey. While Nixon courted Southern conservatives through his "Southern Strategy," he did so subtly, avoiding the overt racial rhetoric Wallace embraced. Humphrey, meanwhile, was burdened by his association with the Johnson administration's civil rights policies, which alienated many Southern voters. Wallace's unapologetic stance on segregation and states' rights offered a clear alternative for those who felt abandoned by both major parties. This dynamic highlights the unique role third-party candidates can play in amplifying fringe ideologies and forcing national conversations on divisive issues.

Practically, Wallace's campaign serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of leveraging division for political gain. While his success was confined to the South, the broader impact of his rhetoric contributed to the polarization of American politics. For those studying political strategy, Wallace's campaign underscores the importance of understanding regional sentiments and the potential consequences of appealing to fear and resentment. Modern politicians and activists can draw lessons from this era, recognizing how issues like race and federal authority remain potent forces in shaping public opinion. Wallace's legacy reminds us that while divisive tactics may yield short-term gains, they often leave lasting scars on the national fabric.

Finally, examining Wallace's 1968 campaign through a descriptive lens reveals a snapshot of a nation in turmoil. The South he addressed was a region in transition, grappling with the end of Jim Crow and the dawn of a new social order. His rallies, attended by thousands, were both a display of defiance and a cry for a bygone era. The five states he won were not just electoral victories but symbols of a deeper cultural resistance. This campaign was more than a political maneuver; it was a reflection of the complexities of race, identity, and power in America. Understanding this chapter requires moving beyond simplistic labels, instead delving into the historical, social, and emotional currents that fueled Wallace's rise.

Understanding the Major Political Parties in the United States

You may want to see also

American Independent Party: Founded to support Wallace's 1968 campaign, emphasizing anti-establishment and conservative platforms

George Wallace, the fiery segregationist governor of Alabama, sought the presidency in 1968 as a third-party candidate. To support his campaign, the American Independent Party (AIP) was founded, a political entity born out of frustration with the established two-party system. This party wasn't merely a vehicle for Wallace's personal ambitions; it represented a coalescing of conservative, anti-establishment sentiment that felt abandoned by both Republicans and Democrats.

The AIP's platform mirrored Wallace's own brand of populism, emphasizing states' rights, law and order, and a staunch opposition to the civil rights movement and federal intervention in local affairs. They capitalized on the anxieties of a segment of the American population grappling with rapid social change, economic uncertainty, and the escalating Vietnam War.

The AIP's strategy was twofold: to appeal to disaffected Southern Democrats who felt betrayed by their party's embrace of civil rights, and to attract conservative Republicans disillusioned with the moderate policies of Richard Nixon. Wallace's fiery rhetoric and unapologetic stance on segregation resonated with these groups, particularly in the Deep South. The AIP's success in securing ballot access in all 50 states and capturing nearly 10 million votes, despite ultimately losing the election, demonstrated the potency of this anti-establishment message.

While the AIP failed to win the presidency, its impact on American politics was significant. It exposed the fault lines within the two major parties and highlighted the enduring appeal of populist, conservative ideologies. The party's legacy can be seen in the continued influence of these themes within the Republican Party, particularly in its more conservative factions.

Understanding the AIP's rise and fall offers valuable insights into the complexities of American politics. It serves as a reminder that political movements often emerge from a sense of alienation and frustration, and that the appeal of anti-establishment rhetoric can be powerful, even if ultimately unsuccessful in achieving electoral victory. The AIP's story is a cautionary tale about the dangers of divisive politics, but also a testament to the enduring struggle for representation and the ever-shifting landscape of American political identity.

Wealth in Politics: Which Party Holds the Financial Advantage?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.5

$29.95

Return to Democratic Party: Rejoined Democrats in the 1970s, moderating views and seeking the 1972 and 1976 nominations

George Wallace's political journey in the 1970s marked a significant shift, as he returned to the Democratic Party, a move that reflected both personal evolution and strategic recalibration. After his high-profile gubernatorial tenure in Alabama and his third-party presidential bid in 1968, Wallace sought to reposition himself within the mainstream of American politics. This return to the Democratic fold was not merely a party switch but a calculated effort to moderate his views and appeal to a broader electorate. By rejoining the Democrats, Wallace aimed to distance himself from the polarizing segregationist image that had defined much of his earlier career, instead focusing on populist economic themes and national aspirations.

The 1972 presidential campaign served as Wallace's first test of this new strategy. Though still a divisive figure, he toned down his rhetoric on racial issues, emphasizing instead his opposition to busing and his support for working-class Americans. This shift allowed him to gain traction in the Democratic primaries, particularly in the South, where he won several states. However, his campaign was abruptly halted by an assassination attempt in Maryland, which left him paralyzed and sidelined from the race. Despite this setback, Wallace's performance demonstrated that his moderated stance had potential, even if it fell short of securing the nomination.

Undeterred, Wallace continued his political rehabilitation, culminating in his 1976 presidential bid. By this time, his views had further softened, and he openly apologized for his past actions on segregation, acknowledging the harm they had caused. This public reckoning was a pivotal moment, signaling a genuine attempt to align with the Democratic Party's progressive wing. Wallace's campaign that year focused on economic populism, appealing to blue-collar voters disillusioned with the establishment. While he again failed to secure the nomination, his efforts underscored a broader trend: even a figure as controversial as Wallace could find a place within the Democratic Party by moderating his views and addressing past wrongs.

Wallace's return to the Democratic Party in the 1970s offers a nuanced lesson in political reinvention. It highlights the importance of adaptability in a shifting political landscape, as well as the potential for personal growth to reshape public perception. For those studying political strategy, Wallace's journey serves as a case study in how a politician can pivot from extremism to moderation, leveraging party affiliation to redefine their legacy. Practically, this requires not just a change in rhetoric but a demonstrable shift in values and priorities, as Wallace's eventual apologies and policy adjustments illustrate.

In retrospect, Wallace's attempts to seek the Democratic nomination in 1972 and 1976 were less about winning the presidency and more about reclaiming legitimacy within the political mainstream. His story reminds us that parties are not static entities but dynamic coalitions capable of absorbing even the most unlikely figures—provided they are willing to evolve. For aspiring politicians, the takeaway is clear: moderation and self-reflection can be powerful tools for rebuilding a career, but they must be genuine to resonate with voters. Wallace's journey, though imperfect, remains a testament to the transformative potential of political reinvention.

Minnesota's Political Landscape: Unraveling the Dominant Party in the North Star State

You may want to see also

Legacy and Party Affiliation: Wallace's shifting stances reflect complex ties to Democrats, independents, and conservative movements

George Wallace's political journey was a labyrinth of shifting allegiances, reflecting the turbulent ideological currents of mid-20th century America. Initially a Democrat, Wallace's early career was marked by a moderate stance, even supporting Harry Truman in 1948. However, by the 1960s, he had embraced segregationist policies, leveraging the Democratic Party's historical ties to the South to advance his "states' rights" agenda. This transformation underscores how party affiliation can be a malleable tool for political survival, especially in regions with deep-seated cultural and racial divisions.

Wallace's 1968 presidential bid as an independent candidate marked a strategic pivot. By running under the American Independent Party banner, he sought to capitalize on national discontent with the Vietnam War and racial integration. This move highlights the appeal of independence as a platform for populist rhetoric, allowing politicians to transcend traditional party constraints while still tapping into conservative sentiments. Wallace's ability to secure nearly 10 million votes demonstrates the potency of such a strategy in polarizing times.

In his final gubernatorial campaigns, Wallace returned to the Democratic Party, but with a softened tone on race. This shift was less about ideological conversion and more about political pragmatism. By the 1980s, the South was undergoing significant demographic and cultural changes, and Wallace's earlier segregationist stance had become politically untenable. His re-affiliation with the Democrats illustrates how party identity can be recalibrated to align with evolving regional and national priorities.

Wallace's legacy complicates the narrative of party affiliation, revealing it as a dynamic rather than static construct. His journey from moderate Democrat to segregationist icon, independent populist, and finally, reconciliatory Democrat, mirrors the broader struggles within the Democratic Party to balance its progressive and conservative wings. For modern politicians, Wallace's story serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of leveraging divisive issues for short-term gain, while also offering insights into the strategic use of party labels to navigate shifting political landscapes.

Ultimately, Wallace's shifting stances underscore the intricate relationship between personal ambition, regional identity, and national politics. His legacy challenges us to view party affiliation not as a rigid marker of ideology, but as a fluid instrument shaped by historical context, personal evolution, and the ever-changing demands of the electorate. Understanding this complexity is crucial for anyone seeking to navigate the fraught terrain of American political identity.

Exploring Sweden's Political Landscape: Parties, Ideologies, and Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Wallace was initially affiliated with the Democratic Party, particularly during his early political career in Alabama.

Yes, George Wallace switched to the Republican Party briefly in 1968 when he ran for president as an independent, but later returned to the Democratic Party.

George Wallace served as Governor of Alabama as a Democrat during all four of his terms (1963–1967, 1971–1979, and 1983–1987).

George Wallace ran for president as a Democrat in 1972 and 1976, though he also ran as an independent in 1968, backed by the American Independent Party.

By the end of his political career, George Wallace remained a Democrat, though his views had moderated significantly from his earlier segregationist stance.