The question of what percentage of the vote a political party needs to secure power or influence is a critical aspect of electoral systems worldwide, varying significantly depending on the country’s political structure. In some systems, such as first-past-the-post, a party may win a majority of seats with less than 50% of the popular vote, while proportional representation systems often require parties to meet a threshold, typically ranging from 3% to 5%, to gain parliamentary representation. Additionally, coalition governments are common in many democracies, where multiple parties must collectively achieve a majority, often necessitating negotiations and compromises. Understanding these thresholds is essential for both voters and parties, as they directly impact governance, policy-making, and the balance of power in a political landscape.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Minimum vote threshold for winning seats

In electoral systems worldwide, the minimum vote threshold for a political party to win seats is a critical mechanism designed to ensure stability and prevent fragmentation. For instance, in Turkey, a party must secure at least 10% of the national vote to enter parliament, a rule that has historically marginalized smaller parties. This threshold, known as a legal threshold, is common in proportional representation systems and serves to discourage the proliferation of minor parties that could complicate coalition-building. In contrast, countries like the Netherlands have no threshold, allowing parties with as little as 0.67% of the vote to win a seat, reflecting a more inclusive approach to representation.

The choice of threshold is not arbitrary; it reflects a country’s political priorities. High thresholds, like Turkey’s 10%, prioritize governmental stability by limiting the number of parties in parliament. However, they can disenfranchise minority voices. For example, in the 2015 Turkish elections, the pro-Kurdish HDP narrowly surpassed the threshold, securing 80 seats, while smaller parties were excluded despite collectively garnering significant support. Conversely, low or non-existent thresholds, as seen in Israel’s 3.25% requirement, foster greater inclusivity but often result in fragmented legislatures and unstable coalitions. Israel’s frequent elections in recent years illustrate the challenges of governing in such an environment.

Implementing a threshold requires careful consideration of a nation’s political landscape. For countries transitioning to democracy, a moderate threshold (e.g., 5%) can strike a balance between stability and representation. For instance, Germany’s 5% threshold allows smaller parties like the Greens and FDP to participate in government while preventing extreme fragmentation. Policymakers must also account for regional dynamics; a one-size-fits-all approach can alienate specific communities. In New Zealand, the Māori Party benefits from a lower threshold in reserved seats, ensuring indigenous representation.

Practical tips for parties navigating threshold systems include coalition-building and strategic campaigning. In systems with high thresholds, smaller parties often form alliances to pool votes, as seen in the Czech Republic’s 2021 elections, where three center-right parties united to surpass the 5% barrier. Additionally, parties should focus on voter education, particularly in systems with complex rules, such as Poland’s 8% threshold for coalitions. Clear communication of the threshold’s implications can mobilize supporters and prevent wasted votes.

Ultimately, the minimum vote threshold is a double-edged sword. While it can streamline governance, it risks excluding diverse perspectives. Countries must weigh their desire for stability against the democratic ideal of inclusive representation. For voters and parties alike, understanding these thresholds is essential for strategic participation in the electoral process. Whether advocating for reform or adapting to existing rules, stakeholders must engage with this mechanism to shape fair and functional political systems.

Unveiling the Enigma: Who is Political Figure Richard Spence?

You may want to see also

Impact of electoral systems on required percentage

The percentage of votes a political party needs to secure power varies dramatically depending on the electoral system in place. In first-past-the-post (FPTP) systems, like those in the United Kingdom or the United States (for congressional elections), a party can win a seat with as little as 20-30% of the vote in a multi-candidate race, provided it’s more than any other single party. This system rewards plurality rather than majority, often leading to governments formed with less than 50% of the popular vote. For instance, in the 2019 UK general election, the Conservative Party won 56% of seats with just 43.6% of the vote.

Contrast this with proportional representation (PR) systems, where the percentage of votes directly correlates to the percentage of seats. In countries like the Netherlands or Israel, a party might need only a small threshold, often around 2-5%, to enter parliament. This lowers the barrier to entry for smaller parties but can lead to fragmented legislatures and coalition governments. For example, in the 2021 Dutch election, 17 parties secured seats, with the largest party winning just 15% of the vote.

Mixed-member proportional (MMP) systems, used in Germany and New Zealand, combine elements of both. Parties must typically clear a threshold (e.g., 5% in Germany) to gain proportional seats, but direct constituency wins can bypass this requirement. This hybrid approach balances local representation with proportionality, though it can still favor larger parties. In the 2021 German election, the AfD party secured 10.3% of the vote, earning them 83 seats, while smaller parties failing the threshold were excluded.

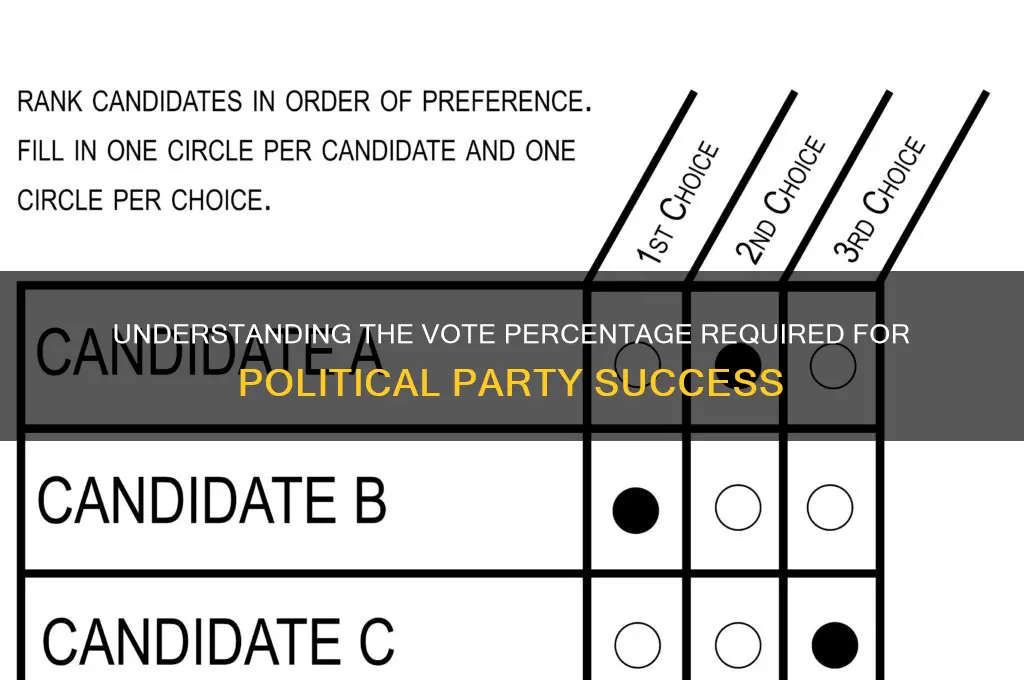

The two-round system (runoff voting), as seen in France, requires a candidate to win an absolute majority (50% +1 vote) in the first round or proceed to a second round. This system ensures winners have broader legitimacy but can lead to strategic voting and alliances. In the 2017 French presidential election, Emmanuel Macron won 66.1% in the runoff after securing just 24% in the first round.

Ultimately, the electoral system dictates not only the percentage needed to win but also the political landscape it fosters. FPTP encourages two-party dominance, PR promotes multi-party systems, and MMP and runoffs strike a middle ground. Understanding these mechanics is crucial for parties strategizing to meet—or manipulate—the required thresholds.

Exploring India's Diverse Political Landscape: Types of Parties

You may want to see also

Coalition formation and vote distribution

In parliamentary systems, a political party typically needs a majority of seats to form a government, but the percentage of the popular vote required to achieve this varies widely. For instance, in the 2019 UK general election, the Conservative Party secured 56% of the seats with just 43.6% of the vote, while in Israel’s 2020 election, the Likud party formed a coalition with 29% of the vote. This disparity highlights how vote distribution and coalition dynamics can dramatically alter outcomes. When no single party achieves a majority, coalition formation becomes critical, and smaller parties with modest vote shares—often as low as 5–10%—can become kingmakers.

Coalition formation is both an art and a science, requiring parties to balance ideological alignment, policy concessions, and seat arithmetic. For example, Germany’s mixed-member proportional system often results in coalitions like the CDU/CSU-SPD "Grand Coalition," formed despite neither party winning a majority. Here, a party with 25–30% of the vote can lead a government by partnering with smaller parties. The key is not just the percentage of votes but how effectively they translate into seats and alliances. Parties must strategize to maximize their influence, often by targeting specific regions or demographics to secure a critical number of seats.

A persuasive argument for coalition governments is their potential to foster inclusivity and stability, but this depends on vote distribution. In fragmented systems like India’s, where regional parties often win 2–5% of the national vote, coalitions are the norm. However, such arrangements can be fragile, as seen in Italy’s frequent government collapses. To succeed, parties must prioritize shared goals over ideological purity, often requiring compromises that may alienate core voters. This delicate balance underscores why vote distribution—not just the percentage—matters in coalition formation.

Practical tips for parties aiming to form coalitions include focusing on swing districts to optimize seat gains, even with a modest vote share. For instance, in Canada’s 2021 election, the Liberal Party won 160 seats with 32.6% of the vote by targeting key ridings. Additionally, parties should cultivate relationships with potential allies early, as post-election negotiations are often rushed. Caution is advised against over-relying on small parties, as their demands can be disproportionate to their vote share. Ultimately, understanding the interplay between vote distribution and coalition dynamics is essential for any party aiming to govern effectively.

Polarized Politics: Are Political Parties Dividing Society Beyond Repair?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of proportional representation in vote needs

Proportional representation (PR) systems fundamentally alter the calculus of vote thresholds for political parties by linking parliamentary seats directly to vote share. Unlike winner-take-all systems, where a party might need 50%+1 vote to secure a single constituency, PR systems distribute seats in proportion to votes received. For instance, a party earning 30% of the national vote in a PR system would typically secure approximately 30% of the parliamentary seats, ensuring representation aligns closely with voter preferences. This mechanism lowers the effective threshold for meaningful representation, encouraging smaller parties to compete and fostering coalition governments.

Consider the Netherlands, a country with a fully proportional system and no formal vote threshold. Here, a party needs only around 0.67% of the national vote to secure a single seat in the 150-member parliament. This ultra-low barrier allows niche parties, such as the Party for the Animals or the Reformed Political Party, to gain representation. In contrast, Germany’s mixed-member proportional system imposes a 5% national vote threshold (or three direct constituency wins) to prevent excessive fragmentation while still accommodating smaller parties like the Greens or Free Democratic Party. These examples illustrate how PR systems balance inclusivity with stability through adjustable thresholds.

However, PR systems are not without challenges. Lower vote thresholds can lead to highly fragmented legislatures, complicating coalition formation and governance. Israel’s PR system, with a 3.25% threshold, often results in fragile coalitions and frequent elections. To mitigate this, some PR systems incorporate mechanisms like higher thresholds or minimum seat requirements. For instance, Turkey’s 10% national threshold aims to limit Kurdish representation, highlighting how PR design can be manipulated for political ends. Parties in PR systems must thus strategize not only to surpass thresholds but also to position themselves as viable coalition partners.

For parties operating in PR systems, understanding the interplay between vote share and seat allocation is critical. A party with 20% of the vote in a 100-seat parliament would secure 20 seats, but its influence could exceed this number if it becomes a kingmaker in coalition negotiations. Practical tips include targeting regions or demographics where the party can maximize vote share, as every additional percentage point translates directly into seats. Additionally, parties should invest in coalition-building skills, as PR systems rarely produce single-party majorities.

In conclusion, proportional representation redefines the vote needs of political parties by prioritizing inclusivity over majoritarianism. While it lowers the threshold for representation, it also demands strategic adaptability from parties navigating coalition dynamics. Whether through low thresholds like the Netherlands or higher barriers like Germany, PR systems offer a flexible framework for translating votes into power. Parties must therefore tailor their strategies to the specific rules of their PR system, ensuring they not only meet the threshold but also maximize their influence in the resulting parliamentary landscape.

Understanding the Blue Party: Political Affiliation and Global Significance

You may want to see also

Historical trends in winning vote percentages

The percentage of votes required to win an election varies widely across electoral systems, but historical trends reveal a fascinating pattern: the winning vote share has been steadily declining in many democracies. In the mid-20th century, majoritarian systems like the UK and Canada often saw winning parties secure 45–50% of the vote. Today, that figure has dropped to 35–40%, with parties forming governments on increasingly smaller mandates. This shift underscores the fragmentation of the political landscape and the rise of multi-party systems, where coalitions and minority governments are becoming the norm rather than the exception.

Analyzing specific examples highlights this trend. In the 1950s, the UK’s Conservative and Labour parties routinely won over 48% of the vote. By contrast, in the 2019 general election, the Conservatives formed a majority government with just 43.6% of the vote. Similarly, in Canada, the 1984 election saw the Progressive Conservatives win 50.03%, while the 2021 election resulted in a Liberal minority government with only 32.6%. These cases illustrate how parties now govern with a smaller share of the electorate’s support, raising questions about mandate legitimacy and governance stability.

This decline in winning vote percentages is not merely a statistical curiosity but a reflection of deeper societal changes. The proliferation of smaller, issue-based parties has diluted the vote, while voter preferences have become more diverse and polarized. For instance, the rise of Green parties in Europe and populist movements in the Americas has siphoned votes from traditional powerhouses. As a result, winning parties must adapt by forming coalitions or governing with minority support, a dynamic that reshapes policy-making and political strategy.

A comparative analysis of proportional representation (PR) systems offers additional insight. In countries like Germany and Sweden, where PR is the norm, winning coalitions often form with a combined vote share of 50% or less. For example, Germany’s 2021 federal election saw the winning coalition secure just 49.4% of the vote. While PR systems inherently distribute power more evenly, they also highlight the global trend of declining vote percentages for governing parties. This suggests that the phenomenon is not limited to majoritarian systems but is a broader feature of modern democracies.

Practical takeaways from these trends are clear: parties must focus on building alliances and broadening their appeal to govern effectively. Voters, in turn, should recognize that their choices contribute to a fragmented political landscape, where no single party may dominate. Understanding these historical shifts is crucial for navigating the complexities of contemporary elections and fostering more inclusive, adaptive governance models.

Exploring the Diverse Political Parties in the United Kingdom

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In a parliamentary system, a political party typically needs to secure more than 50% of the seats in the legislature to form a majority government. However, the percentage of the popular vote required to achieve this varies depending on the electoral system. In some cases, a party can win a majority of seats with less than 40% of the popular vote due to vote distribution and electoral boundaries.

In the United States, a candidate needs to win a majority of the Electoral College votes (270 out of 538) to become president, not a specific percentage of the popular vote. A candidate can win the presidency without securing 50% of the popular vote, as seen in several elections, including 2000 and 2016.

In a proportional representation (PR) system, the percentage of the vote required for a party to gain representation depends on the electoral threshold set by the country. For example, in some PR systems, parties must achieve a minimum threshold (e.g., 3% to 5% of the national vote) to secure seats in the legislature.

To form a coalition government, a party typically needs to secure enough seats in the legislature to reach a majority when combined with its coalition partners. The percentage of the vote required varies, but it often involves parties with smaller vote shares (e.g., 20-30% or less) joining forces to achieve a combined majority.

In a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, a party or candidate only needs to secure a plurality (more votes than any other candidate) in a single-member district to win the seat. This means a candidate can win with as little as 30-40% of the vote if the remaining votes are split among multiple opponents.