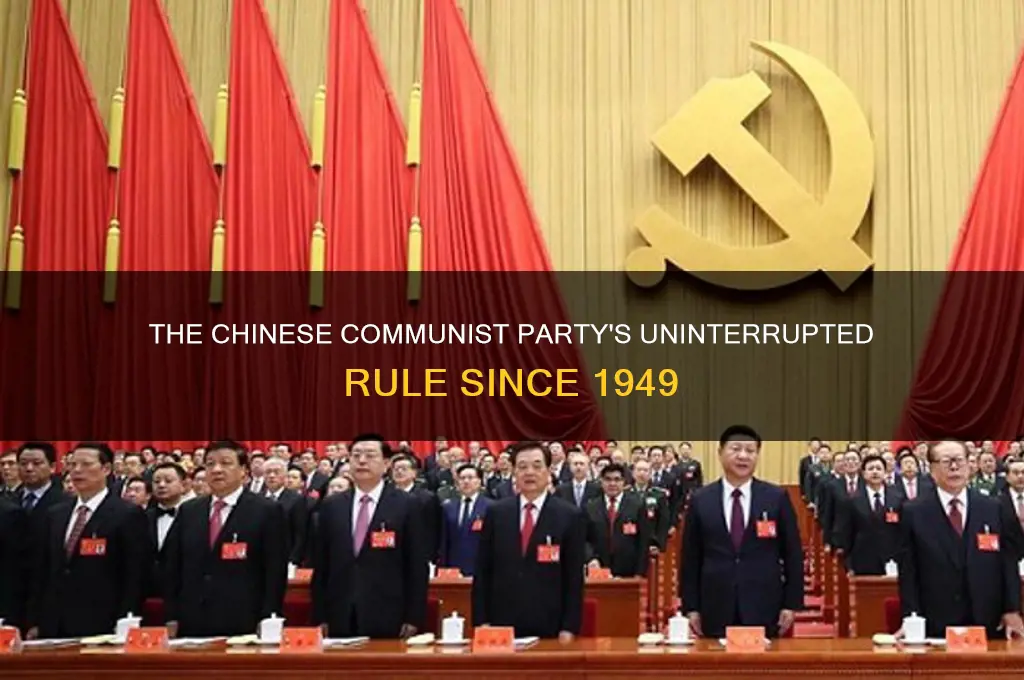

Since 1949, Chinese politics has been dominated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which came to power following the victory of Mao Zedong’s forces in the Chinese Civil War. The CCP established the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949, and has since maintained a monopoly on political power, shaping the country’s governance, ideology, and development. As the sole ruling party, the CCP has overseen significant historical events, including the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and the Reform and Opening-Up era under Deng Xiaoping. Today, under General Secretary Xi Jinping, the CCP continues to play a central role in China’s domestic and foreign policies, emphasizing party discipline, socialist modernization, and national rejuvenation. Its enduring control has made it one of the most influential political organizations in the world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Communist Party of China (CPC) |

| Year Established | 1921 |

| Year of Political Control | 1949 (after the founding of the People's Republic of China) |

| Ideology | Communism, Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, Marxism-Leninism |

| Leadership Structure | General Secretary (highest-ranking official), Politburo, Central Committee |

| Current General Secretary | Xi Jinping (since 2012) |

| Governance System | Single-party socialist republic |

| National Congress | Held every five years to set policies and elect leadership |

| Membership | Over 98 million members (as of 2023) |

| Role in Government | Controls all levels of government, military, and judiciary |

| Economic Model | Socialist market economy |

| International Affiliation | Leading member of the international communist and socialist movements |

| Constitution | Constitution of the People's Republic of China (CPC plays a leading role) |

| Key Policies | Reform and Opening-Up, Belt and Road Initiative, Common Prosperity |

| Symbol | Hammer and sickle |

| Official Media | People's Daily, Xinhua News Agency |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Founding and Rise

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been the dominant political force in China since 1949, shaping the nation's trajectory through revolution, reform, and rapid modernization. Founded in 1921 by intellectuals inspired by Marxist-Leninist ideology, the CCP began as a small, underground movement. Its early years were marked by struggles against warlordism, foreign imperialism, and the rival Kuomintang (KMT). The party's resilience and strategic acumen, particularly under the leadership of Mao Zedong, enabled it to emerge victorious in the Chinese Civil War, establishing the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949.

The CCP's rise to power was fueled by its ability to mobilize the masses, particularly peasants, through land reform and promises of social equality. Mao's agrarian-based revolution contrasted sharply with the KMT's urban and elite-focused policies. Campaigns like the Long March (1934–1935) and the United Front strategy during World War II showcased the party's adaptability and determination. However, the CCP's early governance was not without challenges. Policies like the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962) led to devastating famine, while the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) caused widespread social and economic upheaval. These setbacks underscored the party's ideological rigidity and the dangers of centralized authoritarian rule.

Despite these missteps, the CCP's control over Chinese politics remained unchallenged, largely due to its monopoly on power and its ability to suppress dissent. The turning point came under Deng Xiaoping, who assumed leadership in 1978 and introduced market-oriented reforms. Deng's pragmatic approach, encapsulated in the slogan "socialism with Chinese characteristics," transformed China into an economic powerhouse. The party shifted its focus from class struggle to economic development, attracting foreign investment and lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty. This period marked the CCP's evolution from a revolutionary movement to a technocratic governing body.

Today, the CCP's dominance is reinforced through a combination of ideological control, surveillance, and economic incentives. Under Xi Jinping, who became General Secretary in 2012, the party has centralized power further, emphasizing nationalism and loyalty to the CCP. Xi's anti-corruption campaigns and initiatives like the Belt and Road Project have solidified his authority while expanding China's global influence. However, challenges such as income inequality, environmental degradation, and international tensions test the party's legitimacy. The CCP's ability to adapt to these pressures will determine its continued hold on power in the 21st century.

In summary, the CCP's founding and rise reflect a blend of ideological fervor, strategic adaptability, and authoritarian control. From its revolutionary origins to its current role as a global superpower's ruling party, the CCP has reshaped China's identity and place in the world. Its enduring dominance since 1949 highlights both its strengths and vulnerabilities, offering a unique case study in political survival and transformation.

The Political Awakening of Grange: Factors and Influences Explored

You may want to see also

Mao Zedong’s Leadership and Revolution

Since 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been the dominant force in Chinese politics, shaping the nation's trajectory through its ideologies and leadership. At the heart of this dominance is Mao Zedong, whose leadership and revolutionary vision left an indelible mark on China's political landscape.

The Revolutionary Blueprint: Mao's Ideological Foundation

Mao Zedong's leadership was rooted in his adaptation of Marxist-Leninist theory to China's agrarian context. His concept of a "peasant-led revolution" challenged traditional Marxist focus on the urban proletariat. Through works like *On New Democracy* (1940), Mao outlined a two-stage revolution: first, a democratic revolution against imperialism and feudalism, followed by a socialist transformation. This strategy proved pivotal in mobilizing rural masses, who constituted 80% of China’s population in the 1940s. By framing the CCP as the vanguard of peasant interests, Mao secured a broad base of support, culminating in the 1949 establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

Campaigns of Transformation: Radicalism in Action

Mao’s leadership was characterized by bold, often disruptive campaigns aimed at reshaping Chinese society. The Land Reform Movement (1950–1953) redistributed land to 300 million peasants, dismantling feudal structures. However, the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962) exemplified the risks of ideological zeal over pragmatism. Aiming to overtake the UK’s economy in 15 years, this campaign led to collectivization, backyard steel furnaces, and, tragically, a famine that claimed 15–55 million lives. Despite its failures, the Great Leap Forward underscored Mao’s willingness to experiment radically, a hallmark of his revolutionary approach.

Cultural Revolution: Purging Dissent, Entrenching Control

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was Mao’s final, most tumultuous campaign to eliminate perceived bourgeois elements within the CCP and Chinese society. By mobilizing the Red Guards, largely composed of students aged 15–25, Mao sought to rejuvenate revolutionary spirit. However, the campaign descended into chaos, with schools closed for years, cultural relics destroyed, and millions persecuted. Estimates suggest 500,000 to 2 million deaths during this period. While the Cultural Revolution weakened China economically and socially, it solidified Mao’s cult of personality and ensured his ideological dominance until his death in 1976.

Legacy and Lessons: Mao’s Dual Impact

Mao’s leadership was a paradox of progress and devastation. His policies unified China under a single party, eradicated feudalism, and laid the groundwork for future economic reforms. Yet, his revolutionary zeal often prioritized ideology over human cost. Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s successor, later acknowledged this duality, stating, "Without Mao, there would be no New China, but we must also critically assess his mistakes." For modern leaders, Mao’s legacy serves as a cautionary tale: revolution requires vision, but sustainability demands pragmatism.

Practical Takeaways for Understanding Mao’s Era

To grasp Mao’s impact, study primary sources like *Quotations from Chairman Mao* (the "Little Red Book") alongside critical analyses. Compare Mao’s agrarian focus with Lenin’s industrial emphasis to highlight their differing revolutionary strategies. When analyzing campaigns like the Great Leap Forward, quantify outcomes (e.g., steel production vs. famine deaths) to balance ideological intent with real-world consequences. Finally, consider Mao’s enduring influence on the CCP’s governance style, from centralized authority to mass mobilization tactics still employed today.

Why Politics Matter: Shaping Societies, Policies, and Our Daily Lives

You may want to see also

Deng Xiaoping’s Economic Reforms

Since 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been the dominant political force in China, shaping its governance, policies, and trajectory. Within this framework, Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms stand out as a transformative pivot that redefined China’s role in the global economy. Launched in the late 1970s, these reforms shifted China from a centrally planned, agrarian economy to a market-oriented industrial powerhouse. Deng’s pragmatic approach, encapsulated in his famous phrase “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice,” prioritized economic growth over rigid ideology, setting the stage for China’s unprecedented rise.

The cornerstone of Deng’s reforms was the decentralization of agriculture through the Household Responsibility System. Under this policy, communal farming was dismantled, and land was leased to individual families, incentivizing productivity. This simple yet revolutionary change led to a surge in agricultural output, effectively ending food shortages and freeing rural labor for urban industrialization. For instance, grain production increased by 50% between 1978 and 1984, demonstrating the immediate impact of this reform. Farmers, once bound by collective quotas, now had the autonomy to sell surplus produce in markets, fostering a nascent entrepreneurial spirit.

Simultaneously, Deng established Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in coastal cities like Shenzhen and Xiamen, offering tax incentives and relaxed regulations to attract foreign investment. These zones became laboratories for market experimentation, blending foreign capital with China’s vast labor force. By the 1990s, Shenzhen had transformed from a fishing village into a global manufacturing hub, symbolizing the success of Deng’s export-driven growth strategy. This model was later replicated nationwide, propelling China into becoming the “world’s factory” and lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty.

However, Deng’s reforms were not without challenges. The rapid transition to a market economy exacerbated income inequality and regional disparities. Urban areas flourished, while rural regions lagged, creating a divide that persists today. Additionally, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), though restructured, remained inefficient and heavily subsidized, distorting market competition. Deng’s cautious approach, balancing reform with political control, ensured the CCP’s dominance but also embedded structural inefficiencies that China continues to address.

In retrospect, Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms were a masterclass in pragmatic policymaking, blending ideological flexibility with strategic vision. They not only revitalized China’s economy but also cemented the CCP’s legitimacy by delivering tangible improvements in living standards. While the reforms introduced complexities, their legacy is undeniable: China’s transformation from a closed, impoverished nation to a global economic superpower is a testament to Deng’s bold yet calculated approach. His reforms remain a critical chapter in understanding the CCP’s enduring control and China’s modern identity.

Strengthening Democracy: Strategies for National and State Political Parties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Xi Jinping’s Modern Era Consolidation

Since 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been the dominant force in Chinese politics, shaping the nation's trajectory through various eras of leadership. Xi Jinping's tenure, often referred to as the "Modern Era," marks a significant consolidation of power, both within the party and across Chinese society. This period is characterized by a series of strategic moves aimed at centralizing authority, modernizing governance, and reinforcing the CCP's ideological dominance.

One of the most notable aspects of Xi Jinping's consolidation is the abolition of presidential term limits in 2018, a move that effectively allows him to remain in power indefinitely. This change was not merely procedural but symbolic, signaling a return to a more personalized leadership style reminiscent of Mao Zedong's era. By removing term limits, Xi has ensured continuity in his vision for China, which includes ambitious goals like the "Chinese Dream" and the Belt and Road Initiative. This step, while controversial internationally, has solidified his position as the most powerful Chinese leader in decades.

Xi's consolidation also involves a comprehensive anti-corruption campaign, which has been both a tool for strengthening party discipline and a means to eliminate political rivals. Since its launch in 2012, the campaign has targeted over a million officials, ranging from low-level bureaucrats to high-ranking leaders. While critics argue that it has been used to sideline opposition, supporters view it as a necessary measure to restore public trust in the CCP. The campaign’s success in reducing graft has also freed up resources for Xi’s policy priorities, such as economic restructuring and technological innovation.

Another key element of Xi's era is the emphasis on ideological education and cultural control. The CCP has intensified efforts to promote socialist values and loyalty to the party, particularly among young people. Initiatives like the "Study Xi, Strengthen the Nation" campaign and the integration of Xi Jinping Thought into school curricula reflect this focus. Additionally, tighter regulations on media, the internet, and civil society aim to suppress dissent and ensure that the party’s narrative remains unchallenged. These measures underscore Xi's commitment to maintaining the CCP's ideological monopoly in an increasingly complex and interconnected world.

Finally, Xi's consolidation extends to foreign policy, where China has adopted a more assertive stance on the global stage. From territorial disputes in the South China Sea to economic coercion against countries that challenge its interests, China under Xi has demonstrated a willingness to use its growing power to shape international norms. The Belt and Road Initiative, for instance, is not just an economic project but a strategic effort to expand China’s influence across Asia, Africa, and beyond. This global ambition is a hallmark of Xi's leadership, reflecting his vision of China as a dominant player in the 21st century.

In summary, Xi Jinping's Modern Era Consolidation is a multifaceted strategy to secure the CCP's dominance in Chinese politics and society. Through institutional changes, anti-corruption efforts, ideological control, and assertive foreign policy, Xi has centralized power and set the stage for China’s continued rise. While his methods have drawn criticism, they have undeniably reshaped the country’s political landscape, ensuring that the CCP remains the unchallenged ruler of China since 1949.

Boston Bombers' Political Affiliations: Unraveling the Truth Behind Their Motives

You may want to see also

CCP’s Monopoly on Political Power

Since 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has maintained an unyielding monopoly on political power in China. This dominance is not merely a historical artifact but an actively enforced system, shaped by a combination of ideological control, institutional design, and strategic suppression of dissent. The CCP’s grip on power is so absolute that it permeates every level of governance, from local village committees to the highest echelons of state leadership. This monopoly is enshrined in China’s constitution, which explicitly states that the CCP leads all aspects of Chinese society, effectively eliminating any possibility of political competition.

One of the key mechanisms sustaining the CCP’s monopoly is its control over the state apparatus. The Party operates through a system known as "Party-State fusion," where CCP committees exist within every government institution, ensuring that Party loyalty supersedes bureaucratic neutrality. For instance, the Organization Department of the CCP is responsible for appointing officials across the country, effectively making it the ultimate arbiter of political careers. This system ensures that those in power are not only competent but also ideologically aligned with the Party’s goals, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of control.

Another critical aspect of the CCP’s monopoly is its suppression of alternative political voices. Since the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, the Party has employed a combination of censorship, surveillance, and legal repression to stifle dissent. The Great Firewall, for example, blocks access to foreign websites and monitors domestic online activity, while laws like the National Security Law in Hong Kong criminalize opposition to the Party. These measures are not just reactive but proactive, aiming to preempt any challenge to the CCP’s authority before it gains momentum.

To maintain legitimacy, the CCP has also cultivated a narrative of economic prosperity and national rejuvenation. By delivering rapid economic growth and lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty, the Party has created a tacit social contract: political obedience in exchange for material improvement. This approach, however, is not without risks. As economic growth slows and social inequalities widen, the CCP faces increasing pressure to address public grievances without loosening its grip on power. Its response often involves doubling down on control, as seen in the crackdown on tech giants and the tightening of ideological education in schools and universities.

In conclusion, the CCP’s monopoly on political power is a multifaceted system rooted in institutional control, ideological dominance, and strategic repression. While it has delivered stability and economic growth, its sustainability depends on its ability to adapt to evolving societal demands without compromising its authoritarian structure. For observers and policymakers, understanding this monopoly is crucial to navigating China’s complex political landscape and predicting its future trajectory.

Advancing Women's Rights: Which Political Party Leads the Charge?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Communist Party of China (CPC) has been in control of Chinese politics since 1949.

The CPC gained control after defeating the Kuomintang (KMT) in the Chinese Civil War, leading to the establishment of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949.

No, the Communist Party of China has maintained a monopoly on political power since 1949, with no other party holding national governance.

The CPC is the sole ruling party and oversees all aspects of governance, including the state, military, and society, through its leadership and policies.