Gerrymandering is a form of electoral manipulation in the United States, where voting maps are strategically drawn to favour one political party over another. This practice undermines the democratic process by allowing politicians to choose their voters instead of the other way around. While the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act prohibit racial discrimination in redistricting, the Supreme Court has ruled that federal courts cannot intervene in cases of partisan gerrymandering. This has sparked debates about the role of the judiciary in addressing gerrymandering and prompted the exploration of alternative solutions, such as independent redistricting commissions and legislative reforms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The US Constitution and racial gerrymandering

The US Constitution does not explicitly prevent gerrymandering. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that federal courts have no authority to decide whether partisan gerrymandering violates the Constitution. This ruling, decided by a 5-4 margin, stated that there is no "objective measure" in the Constitution for determining whether a districting map treats a political party unfairly.

Despite this, the US Constitution and the Voting Rights Act prohibit racial discrimination in redistricting. The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment have been used to argue against racial gerrymandering. The Fourteenth Amendment states that:

> "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

The Fifteenth Amendment has also been used to argue against racial gerrymandering, as seen in the case Gomillion v. Lightfoot, where the Court found a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment in the redrawing of a municipal boundary line that excluded all but four or five of 400 African-Americans but no whites, thus perpetuating white domination of municipal elections.

In addition, the Supreme Court has ruled that if race is the predominant factor in the drawing of district lines, a strict scrutiny standard of review is to be applied. This means that the state must demonstrate a compelling governmental interest in creating a majority-minority district and that the redistricting plan was narrowly tailored to achieve that interest.

The Constitution's Declaration: A Republic is Born

You may want to see also

Federal courts and gerrymandering

Gerrymandering is a form of electoral manipulation in the United States where voting maps are drawn to favour one political party over another. This can take the form of partisan gerrymandering, which strengthens one party while weakening its opponents; bipartisan gerrymandering, which protects incumbents from multiple parties; and racial gerrymandering, which seeks to maximise or minimise the impact of certain racial groups.

Federal courts have historically played a role in addressing gerrymandering. The Supreme Court's 1962 ruling in Baker v. Carr established that federal courts could review state legislative redistricting cases. In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled in Wesberry v. Sanders that Georgia's congressional district mappings violated Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution.

However, the Supreme Court has also struggled with gerrymandering cases, as in Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) and Gill v. Whitford (2018). In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts could not intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases, stating that it was a nonjusticiable political question. This decision effectively left it to states and Congress to develop remedies to challenge and prevent gerrymandering.

Despite this ruling, federal courts have continued to hear cases related to racial gerrymandering and violations of the one-person, one-vote principle. For example, a federal court in Michigan ruled in 2019 that the state's Republican-led redistricting was an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. Similarly, a federal district court in Ohio found the state's district maps drawn by Republican lawmakers to be unconstitutional.

While the Supreme Court has limited the role of federal courts in addressing partisan gerrymandering, it has affirmed that such claims can still be decided in state courts under their own constitutions and laws. This mixed approach to gerrymandering cases highlights the ongoing legal complexities surrounding this issue in the United States.

The Fundamentals of a Written Constitution

You may want to see also

Redistricting and gerrymandering

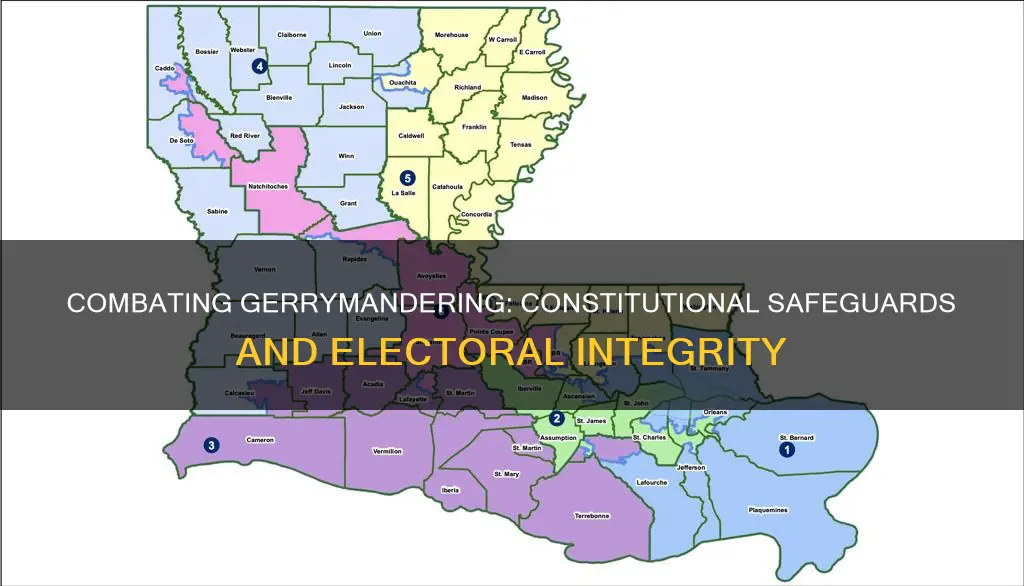

Redistricting is the process of redrawing legislative and congressional district lines following the census. This process is critical to democracy as it ensures that districts are equally populated and representative of a state's population. However, redistricting can also be used to manufacture election outcomes that favour a particular political party, a practice known as gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering occurs when district boundaries are drawn with the intention of influencing election results. This often involves the use of two basic techniques: "cracking" and "packing". Cracking involves splitting groups of voters with similar characteristics across multiple districts, diluting their voting strength. On the other hand, packing involves crowding voters of a particular party or identity group into a small number of districts, limiting their influence.

The Supreme Court's 2019 ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause has been criticised for effectively allowing partisan gerrymandering by making it more difficult to challenge gerrymandering in federal court. The Court ruled that federal courts cannot decide whether partisan gerrymandering goes too far, stating that the Constitution provides no objective measure for assessing the fairness of districting maps. However, the Court noted that partisan gerrymandering claims can still be decided in state courts under their own constitutions and laws.

Despite the potential for abuse, some states have taken steps to address gerrymandering. Several states have passed laws delegating redistricting power to bipartisan or citizens' commissions, although the effectiveness of these commissions varies. Additionally, the For the People Act, which would have required independent redistricting commissions in all 50 states, was proposed by Congressional Democrats in 2021 but failed to pass.

In conclusion, while redistricting is an important process for ensuring fair and equal representation, gerrymandering can undermine the democratic process by empowering politicians to choose their voters. Addressing gerrymandering requires a combination of legal reforms, independent commissions, and increased transparency to ensure that district maps accurately represent the preferences of voters.

The Constitution's Nine Pillars: Understanding the Foundation of US Law

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$332.5 $350

Gerrymandering and political parties

Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing the boundaries of electoral districts in a way that gives one political party an unfair advantage over its rivals. The term gerrymander was first used in 1812 in reaction to a redrawing of Massachusetts state senate election districts under then-governor Elbridge Gerry. The practice has since been used by political parties in the redistricting process to gain control of state legislation and congressional representation and to maintain that control over several decades, even in the face of shifting political changes in a state's population.

The primary goal of gerrymandering is to maximize the effect of supporters' votes and minimize the effect of opponents' votes. This is done through two basic techniques: cracking and packing. Cracking involves dividing groups of voters with similar characteristics, such as party affiliation, across multiple districts, thereby diluting their voting strength. Packing, on the other hand, involves concentrating opposition voters into a few districts, wasting their extra votes.

In the United States, redistricting typically occurs every ten years after the decennial census. This process is often controlled by state legislators and, in some cases, the governor. When one party controls both the state's legislative bodies and the governor's office, they are in a strong position to gerrymander district boundaries to their advantage. The Supreme Court of the United States has struggled with partisan gerrymandering cases, such as in Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) and Gill v. Whitford (2018).

In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause that federal courts have no authority to decide whether partisan gerrymandering goes too far. This decision has been criticized for opening the door for racial discrimination in redistricting, as there is often a correlation between party preference and race. Despite this setback, efforts continue to enhance transparency, strengthen protections for communities of color, and ban partisan gerrymandering in congressional redistricting through reform legislation.

The Constitution's Date: Where and Why?

You may want to see also

Gerrymandering and the Supreme Court

Gerrymandering is a form of electoral manipulation in the United States, where district boundaries are drawn to favour one political party over another. This is done by either "cracking", which involves splitting voters of the same party across multiple districts, or "packing", which involves concentrating voters of the opposing party into a single district. The result is that the voting strength of the split group is diminished, and the concentrated group is all but guaranteed to win in their district.

The Supreme Court has had a significant role in addressing gerrymandering, with varying approaches over time. In 1962, the Supreme Court ruled in Baker v. Carr that federal courts could review state legislative redistricting issues. In 1963, the Court decided Wesberry v. Sanders, ruling that Georgia's congressional district mapping violated Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act, one of the most successful civil rights measures in history, was passed. However, the Supreme Court has since weakened it through decisions such as Shelby County v. Holder in 2013 and Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee in 2021.

In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering claims could not be brought before federal courts, stating that the Constitution provides no objective measure to assess the fairness of district maps. This decision opened the door for states to defend racially discriminatory maps on partisan grounds, as there is often a correlation between party preference and race. Despite this, the Court maintained that racial gerrymandering, which aims to maximise or minimise the impact of racial minority votes, remains unconstitutional, as decided in Miller v. Johnson in 1995.

The Supreme Court's most recent ruling on gerrymandering in 2024, Alexander v. South Carolina NAACP, has caused significant controversy. The Court ruled that if a map is gerrymandered along partisan lines, it cannot intervene, even if the map is also racially gerrymandered. This decision has been criticised for making it more difficult for minority voters to prove racial gerrymandering and for further eroding voting rights protections. The Court's conservative supermajority has been accused of prioritising partisan interests over democratic principles and dismantling equal voting protections.

The Constitution's Promotion of the Preamble's Intent

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No part of the US Constitution explicitly prevents gerrymandering. However, the Supreme Court has held that if a jurisdiction's redistricting plan violates the Equal Protection Clause or the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a federal court must order the jurisdiction to propose a new plan.

Gerrymandering allows politicians to choose their voters, instead of the other way around. Partisan gerrymandering can allow a majority party to win more seats than expected based on the total votes cast for its candidates.

Gerrymandering can be prevented by limiting the power of self-interested politicians in the map-making process. This can be done through the use of independent redistricting commissions (IRCs), which are separate bodies from the state legislature that draw districts for congressional and state legislative elections. Another way is to pass the Freedom to Vote Act, which would give federal courts the ability to determine when gerrymandering has gone too far.