Homer Plessy was an American shoemaker and civil rights activist who was best known as the plaintiff in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Plessy was a member of the Citizens' Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Act, which required separate accommodations for black and white people on railroads. He challenged the act on the basis that it violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which provided for equal protection under the law. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled against Plessy, upholding the separate but equal doctrine and solidifying the establishment of the Jim Crow era.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of the case | May 18, 1896 |

| Name of the case | Plessy vs. Ferguson |

| Name of the plaintiff | Homer Plessy |

| Name of the defendant | John Howard Ferguson |

| Court | U.S. Supreme Court |

| Constitutional Amendments believed to be violated | Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments |

| Ruling | Upheld the Separate Car Act |

| Reasoning | The law did not reimpose slavery and accommodations provided to each race were equal |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

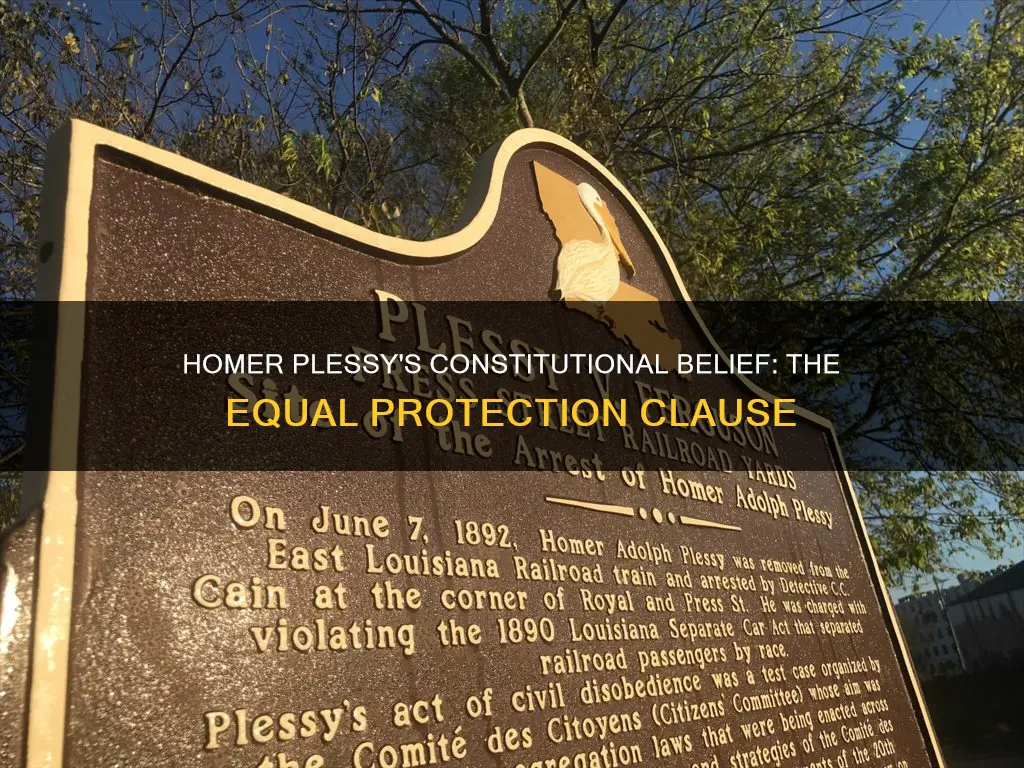

Homer Plessy's arrest

On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, a shoemaker and civil rights activist, was arrested for sitting in a whites-only train compartment. Plessy, who was 7/8 white, had purchased a first-class ticket for the East Louisiana Railroad running between the Press Street Depot in New Orleans and Covington, Louisiana. He was challenged by the conductor, J.J. Dowling, who asked him to leave the "whites-only" car. Plessy refused, and the conductor stopped the train and returned with a private detective, Chris C. Cain, who arrested him.

Plessy's arrest was part of a planned act of civil disobedience organized by the Comité des Citoyens (Committee of Citizens), a group of prominent Black, Creole of color, and white Creole New Orleans residents who opposed Louisiana's Separate Car Act of 1890. This law required separate accommodations for Black and white passengers on railroads, including separate railway cars. The Comité des Citoyens, with the cooperation of the East Louisiana Railroad, staged Plessy's act of civil disobedience to challenge the law and test its constitutionality.

Plessy was charged with violating the Separate Car Act and appeared in criminal court before Judge John Howard Ferguson. He was represented by New Orleans lawyer James Walker, who argued that the Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution, which provided for equal protection under the law. Judge Ferguson ruled against Plessy, upholding the law on the grounds that Louisiana had the right to regulate railroads within its borders.

Plessy appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which unanimously upheld Judge Ferguson's ruling in December 1892. The case eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard the case in 1896 as Plessy v. Ferguson. The Supreme Court ruled against Plessy, establishing the "separate but equal" doctrine as a legal basis for segregation laws, which remained in effect until the 1950s and 1960s. In 2022, Louisiana granted Plessy a posthumous pardon under a state law aimed at rectifying convictions related to racial discrimination.

Federal Statute and Constitution: What's the Relationship?

You may want to see also

The Comité des Citoyens

To bring their test case to court, the Comité des Citoyens staged an act of civil disobedience. They recruited Homer Plessy, who was 1/8 African American, to violate the Separate Car Act by riding in a "whites-only" passenger car. On June 7, 1892, Plessy purchased a first-class ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad and sat in the "whites-only" section. When conductor J. J. Dowling, who was in on the plan, collected Plessy's ticket, he asked him to leave the "whites-only" car. Plessy refused, and the conductor stopped the train and returned with Detective Chris C. Cain, who arrested Plessy and took him to jail.

Prohibition's Constitutional Legacy: A Historical Review

You may want to see also

The Separate Car Act

On June 7, 1892, Plessy, who was seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth African, purchased a first-class ticket to Covington and boarded the East Louisiana Railroad's Number 8 train, expecting to be forced off or arrested. He was arraigned in October 1892 and represented by lawyer James Walker, who argued that the Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which provided for equal protection under the law. Walker also challenged the authority of train officers to assign passengers based on race.

Judge John Howard Ferguson denied Walker's petition, stating that Louisiana had the right to regulate railroad companies within its borders. Plessy's case then went to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which upheld Ferguson's ruling, citing precedents from Northern states. Plessy's lawyer then applied for a writ of error, which was accepted by the U.S. Supreme Court. In May 1896, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy, upholding the Separate Car Act as constitutional and asserting that it did not violate the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments. This decision solidified the "separate but equal" doctrine, which would be used to assess the constitutionality of racial segregation laws.

Legislative Branch: Constitutional Foundation of US Lawmaking

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.99 $14.5

The US Supreme Court case Plessy v Ferguson

Homer Plessy, a mixed-race man, believed that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution provided for equal protection and treatment under the law. On June 7, 1892, Plessy deliberately boarded a whites-only train car in New Orleans, violating Louisiana's Separate Car Act of 1890, which mandated "`equal, but separate`" railroad accommodations for white and black passengers. This act of civil disobedience set in motion the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which would have far-reaching implications for racial segregation laws in the country.

Plessy was charged under the Separate Car Act and represented by New Orleans lawyer James Walker. They challenged the Act's constitutionality, arguing that it violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments by assigning passengers based on race and authorizing train officers to refuse service. However, Judge John Howard Ferguson denied their request, asserting Louisiana's right to regulate railroad companies within its borders. Plessy then appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which unanimously upheld Ferguson's ruling, citing precedents from other states.

Not deterred, Plessy took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was heard in 1893. Despite their efforts, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy in a 7-1 decision on May 18, 1896. The Court upheld the Louisiana law, stating that it did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment, which established legal equality between whites and blacks but did not require the elimination of all "distinctions based upon color." This ruling set a precedent for the "separate but equal" doctrine, legitimizing state laws mandating racial segregation in the South and providing momentum for further segregationist legislation.

The Plessy v. Ferguson decision had immediate and long-lasting consequences. It effectively erased the legislative gains of the Reconstruction Era, and states swiftly adopted oppressive laws that institutionalized racial segregation. The ruling also influenced education, with underfunding of black schools and the reinforcement of segregation in school systems. The "separate but equal" doctrine was later affirmed in cases like Lum v. Rice (1927), where a Mississippi public school for white children was upheld in its right to exclude a Chinese American student. The impact of Plessy v. Ferguson extended well into the 20th century, with legally enforced segregation in the South persisting until the 1960s.

The Constitution's Due Process: A Fundamental Right

You may want to see also

The end of an era of radical Black activism in New Orleans

Homer Plessy was born into a French-speaking Creole family in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1892, Plessy was arraigned before Judge John Howard Ferguson in the Orleans Parish criminal district court. He was represented by New Orleans lawyer James Walker, who submitted a plea challenging the jurisdiction of the trial court by claiming that the Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution.

The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments provided for equal protection under the law. Plessy's lawyer argued that the Separate Car Act "impermissibly clothed train officers with the authority and duty to assign passengers on the basis of race and with the authority to refuse service." This plea deliberately did not specify Plessy's race. However, Plessy was a man of mixed race, with a white Frenchman as his paternal grandfather and a free woman of colour as his maternal grandmother.

The case, Plessy v. Ferguson, was heard by the Supreme Court in 1896. The ruling upheld a Louisiana state law that allowed for "equal but separate accommodations for the white and coloured races." This marked a defeat for Black activists in New Orleans, as it rolled back the major civil rights gains achieved during Reconstruction. The era of radical Black activism in New Orleans, which had included the fight for universal suffrage, civil rights, and integrated public schools, came to an end.

Prior to this, Black activists in New Orleans had made significant strides. For example, Oscar Dunn, a free Black American who spoke both English and French, had built ties with English-speaking Black people and French-speaking Creoles. He advocated for universal suffrage, civil rights, and the well-being of freedmen. Another activist, Ludger Boguille, whose parents had come to New Orleans from Haiti, broke the law before the Civil War by teaching an enslaved person. During the war, he and other Economy Society members advocated for Radical Republican causes, including equal rights for Black people.

Exploring Article 2: A Multi-Part Constitutional Journey

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Homer Plessy believed that the Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution.

The Thirteenth Amendment prohibited slavery and Plessy's lawyers believed that the Separate Car Act imposed "a badge of servitude" on him.

The Fourteenth Amendment prohibited states from denying anyone "the equal protection of the laws". Plessy, who could have passed for white, chose not to turn his back on his African ancestry and tried to protect his rights.

No, the court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment pertained only to "political equality" and not "social equality".