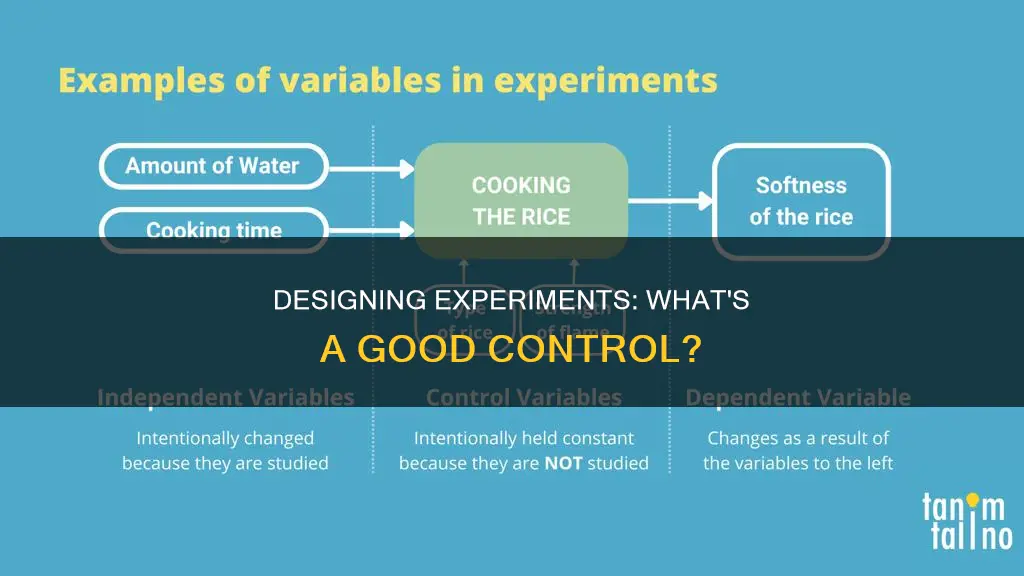

Experimental controls are essential to the scientific method, helping researchers overcome their sensory limits and generate reliable, unbiased, and objective results. Controls help distinguish between the signal and the background noise inherent in natural and living systems, and they also help account for errors and variability in the experimental setup and measuring tools. In experimental design, the creation of experimental conditions is of utmost importance. Experiments require at least two conditions to measure the independent variable and determine its effect on the dependent variable. Typically, an experiment is designed with a control condition and an experimental condition, with subjects in the control group engaging in a benign but related task. Random assignment is a common method used to control extraneous variables across conditions, although it does not guarantee complete control over all variables. Experimental controls are crucial in various fields, from A/B testing in product development to drug trials in medicine, where the standard treatment serves as the control condition when compared to a new medication or procedure.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The importance of controls in experiments

Controls are an essential component of experiments, providing unbiased and objective results that can be trusted and built upon. They are a critical tool to overcome the limitations of human senses and observation methods, ensuring that results are not just random occurrences.

In experimental design, the control condition is the constant, the baseline against which the effects of the independent variable can be measured. For example, in a drug trial, the control group might receive a 'sugar pill', lacking the active ingredient, while the treatment group receives the actual drug. This allows researchers to attribute any improvement in the treatment group over the control group to the drug's effects and not to participants' expectations. Controls help scientists distinguish between the "signal" and the background "noise" in natural and living systems. For instance, in the detection of gravitational waves, four-dimensional reference points were used to filter out the background noise of the cosmos.

Controls are also used to account for errors and variability in the experimental setup, materials, and measuring tools. For example, a negative control in an enzyme assay would test for unrelated background signals from the assay or measurement. In a between-subjects experiment, participants are divided into groups, with each group tested in only one condition. It is essential that these groups are highly similar, with similar proportions of men and women, average IQs, levels of motivation, and health problems. This is achieved through random assignment, ensuring that any differences observed between the groups are due to the variable being tested and not due to confounding variables.

However, random assignment does not guarantee the control of all extraneous variables. For instance, participants in one condition might, by chance, be older or more motivated than those in another condition. Nevertheless, random assignment has been found to work better than expected, especially with large samples. Furthermore, the inferential statistics used to interpret the results can account for the "fallibility" of random assignment.

In some cases, such as medical experiments, it may be unethical to have a "no treatment" control group. In such situations, the control condition becomes the standard treatment, with the experimental condition being the new treatment being tested. Proper experimental design is crucial, and researchers should use pre-validated tasks, conduct pilot tests, and debrief subjects to ensure the adequacy of the tasks.

George W. Bush: Constitutional Violator in Chief

You may want to see also

The role of controls in overcoming sensory limits

Controls are an integral part of experiments, helping to overcome sensory limits and generating reliable, unbiased, and objective results. The scientific method, through hypothesis-testing and controlled experimentation, is the only way to systematically overcome the limits of our sensory apparatus.

Empirical research is based on observation and experimentation, and while influential works by philosophers such as Charles Peirce and Karl Popper do not explicitly mention controls, their importance for solid and reliable results is implicit. Roger Bacon, in his Novum Organum Scientiarum in 1620, emphasised the use of artificial experiments to provide additional evidence for observations, marking the beginning of the concept of controlling experiments.

In experimental design, the creation of experimental conditions is essential. Experiments typically require at least two conditions to measure the independent variable's effect on the dependent variable. One of these conditions is the control, which serves as a baseline for comparison. In a between-subjects experiment, participants are assigned to different conditions, with random assignment being a common method to control extraneous variables. However, random assignment does not guarantee the control of all variables, and larger sample sizes are generally needed for more reliable conclusions.

The use of control groups is prevalent in various fields, such as medical experiments, where the control group may receive the standard treatment, and the experimental group receives a new medication. In A/B testing, control groups are also essential, providing a reference point to evaluate the effects of new changes or features. Proper experimental treatments are crucial, and researchers should use pre-validated tasks, conduct treatment manipulation checks, and perform pilot tests to ensure adequate experimental design.

Ohio Clubs: Constitutions Needed?

You may want to see also

Control conditions in treatment effectiveness research

Control conditions are a critical component of experimental research, particularly in the field of treatment effectiveness. The primary purpose of control conditions is to ensure unbiased, objective observations and measurements of the dependent variable in response to the experimental setup. Experimental research, often regarded as the "gold standard" in research designs, involves manipulating one or more independent variables as treatments, randomly assigning subjects to different treatment levels, and observing the outcomes on dependent variables.

One common approach in treatment effectiveness research is the use of between-subjects experiments. In this design, participants are divided into two groups: the treatment group and the control group. The treatment group receives the intervention or treatment being tested, while the control group serves as a baseline for comparison. This random assignment helps minimise biases that could skew the results, allowing researchers to attribute any observed differences between the groups to the specific treatment being tested.

In the context of treatment effectiveness, the control condition typically involves subjects engaging in a benign but related task. This task should be similar in duration, information requirements, experimenters involved, and the level of interest as the experimental condition. For example, in drug trials, the control group may receive a placebo, an identical-looking pill lacking the active ingredient, while the treatment group receives the actual medication. Alternatively, in psychotherapy research, the control group may engage in unstructured discussions about their problems, while the treatment group receives a specific therapeutic intervention.

When designing control conditions, it is essential to consider the sample size needed to achieve statistical significance. Larger sample sizes generally lead to more reliable conclusions by reducing random variation. However, practical limitations, such as the available population and time constraints, must also be considered. Additionally, researchers should aim to match participants across conditions on key variables, such as gender, age, IQ, and health status, to ensure that any observed differences are due to the treatment rather than these extraneous factors.

In some cases, researchers may opt for within-subjects experiments, where each participant experiences all levels of the independent variable. This design can be useful when it is not feasible or ethical to assign participants to a single condition. For example, in medical experiments, withholding treatment may be unethical, so the control condition becomes the standard treatment of care, compared to the new treatment being tested.

Prayer and the Constitution: A Divine Intervention?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$237.26 $319

Random assignment and extraneous variables

Random assignment is a critical aspect of experimental design, particularly in the social sciences, where it is used to control extraneous variables across conditions. In a between-subjects experiment, participants are randomly assigned to different groups, ensuring that the groups are, on average, highly similar. For instance, in a study on the effectiveness of treatments for agoraphobia, participants with this condition might be randomly assigned to three different treatment groups. To ensure the groups are comparable, the trauma and neutral conditions should include similar proportions of men and women, similar average IQs, and similar average levels of health problems. This process of random assignment helps to control extraneous variables so that they do not become confounding variables.

However, it is important to note that random assignment does not guarantee the complete control of all extraneous variables. There is always a chance that participants in one condition may differ significantly from those in another condition in terms of age, fatigue levels, motivation, or depression levels. Nonetheless, random assignment is generally effective, especially for large samples. Inferential statistics used by researchers also account for the potential "fallibility" of random assignment. Additionally, any confounding variables resulting from random assignment are likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated.

The use of control groups is another essential aspect of experimental design. A control group serves as a baseline for comparison, allowing researchers to attribute any observed differences between the control and treatment groups to the specific variable being tested. For example, in drug trials, one group receives a placebo or "sugar pill," which lacks the active ingredient, while the treatment group receives the actual medication. This ensures that any improvement in the treatment group is due to the drug's effects and not the participants' expectations. Similarly, in A/B testing, users are randomly assigned to either the control group, which uses the current version of a product or website, or the treatment group, which receives the new version with changes or features being tested.

The size of the control and treatment groups can impact the meaningfulness of the results. Generally, larger sample sizes lead to more reliable conclusions as they reduce random variation. However, practical considerations, such as traffic volume and test duration, must also be taken into account when determining group size. Experimental controls are crucial for accurate experiments, and by using proper controls, researchers can make data-driven decisions and draw accurate conclusions, contributing valuable insights to their respective fields.

Understanding Constitutional Privileges and Immunities

You may want to see also

Control groups as a baseline for comparison

Control groups are an essential component of experimental research, serving as a baseline for comparison with the treatment or experimental group. This research design allows scientists to isolate the effects of the independent variable and determine cause-and-effect relationships accurately.

In a typical experiment, one group of subjects receives a treatment or intervention, while the control group does not. This control group acts as a reference point, helping to distinguish between the actual effects of the treatment and any random events or background noise. For instance, in a drug trial, the control group might receive a placebo, an identical-looking pill without the active ingredient, to factor out the psychological impact of taking a pill.

The control group is also crucial for overcoming the limitations of human senses and equipment, ensuring that observations are unbiased and objective. By comparing the control and treatment groups, researchers can account for errors and variability in the experimental setup and measuring tools. This is particularly important when dealing with complex problems in fields like physics and biology.

When designing an experiment, researchers must carefully select participants for the control and treatment groups. Random assignment is commonly used to minimise biases and ensure that the groups are highly similar in terms of age, gender, IQ, motivation, and health status. While randomisation does not guarantee the control of all variables, it helps improve the reliability of the results, especially with large samples.

Additionally, the size of the control and treatment groups can impact the meaningfulness of the results. Generally, larger sample sizes lead to more reliable conclusions by reducing random variation. However, researchers must balance this with practical considerations, such as the available resources and time constraints.

Basement Finishing in West Hartford, CT: What Constitutes 'Finished'?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A control condition is a group that engages in some benign but related task, which should take a similar amount of time, require the same kind and amount of information, involve the same experimenters, and engage a similar amount of interest as the experimental condition. The purpose of a control condition is to provide a reliable point of comparison to help make data-driven choices about which changes to implement.

There are between-subjects experiments and within-subjects experiments. In a between-subjects experiment, each participant is tested in only one condition. For example, a researcher might assign half of the participants to write about a traumatic event and the other half to write about a neutral event. In a within-subjects experiment, each participant experiences all levels of the independent variable.

In a drug trial, the control condition becomes the standard treatment, compared with the experimental condition provided by a new medication. In this case, the control group receives the standard treatment or a placebo, while the experimental group receives the new medication.