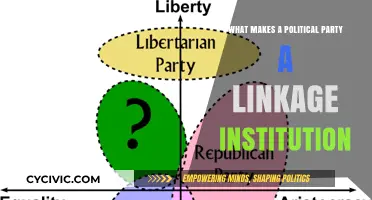

Interest groups and political parties, though both integral to the political landscape, serve distinct roles and operate with different objectives. While political parties are primarily focused on gaining and maintaining political power through winning elections and forming governments, interest groups aim to influence policy outcomes by advocating for specific issues or causes that align with their members' interests. Unlike political parties, which typically represent a broad spectrum of ideologies and seek to appeal to a wide electorate, interest groups are often more specialized, concentrating on niche areas such as environmental protection, labor rights, or business interests. Additionally, political parties are hierarchical organizations with formal structures and leadership, whereas interest groups can range from loosely organized grassroots movements to well-funded lobbying organizations. This fundamental difference in purpose, scope, and structure underscores the unique contributions of each to the democratic process.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Focus and Goals: Interest groups advocate specific issues, while parties seek overall political power

- Membership Structure: Parties require formal membership; interest groups often have looser affiliations

- Electoral Involvement: Political parties run candidates; interest groups influence elections indirectly

- Policy Influence: Interest groups lobby for policies; parties create and implement broader agendas

- Funding Sources: Parties rely on donations and dues; interest groups often use grants and fees

Focus and Goals: Interest groups advocate specific issues, while parties seek overall political power

Interest groups and political parties operate within the same democratic ecosystem but with fundamentally different objectives. Interest groups, such as the Sierra Club or the National Rifle Association, are laser-focused on advancing specific issues—environmental conservation or gun rights, respectively. Their success is measured by policy wins in their niche area, not by securing control of government institutions. In contrast, political parties like the Democrats or Republicans aim for comprehensive political power, seeking to win elections and shape the entire spectrum of public policy. This distinction in focus means interest groups can afford to be single-issue advocates, while parties must appeal to a broader electorate with diverse priorities.

Consider the strategic implications of this difference. Interest groups often employ targeted lobbying, grassroots mobilization, and litigation to achieve their goals. For instance, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) focuses on legal battles to protect civil liberties, while the U.S. Chamber of Commerce advocates for pro-business policies. These groups don’t need to win elections; they need to influence policymakers. Political parties, however, must build coalitions, craft platforms, and run candidates who can appeal to a wide range of voters. A party’s success is tied to its ability to balance competing interests and maintain a broad base of support, whereas an interest group’s strength lies in its ability to rally intense, issue-specific passion.

This divergence in goals also affects how these entities engage with the public. Interest groups often thrive on niche expertise and can afford to use technical language or specialized arguments to sway policymakers. For example, the American Medical Association (AMA) leverages its authority on healthcare issues to influence legislation. Political parties, on the other hand, must communicate in broad, accessible terms to appeal to a diverse electorate. They cannot afford to alienate voters by focusing too narrowly on one issue, as their goal is to win power across multiple levels of government.

Practical tip: If you’re involved in advocacy, understand your role. Are you part of an interest group pushing for a specific policy change, like lowering prescription drug prices? Focus on data, expertise, and targeted pressure campaigns. Or are you working within a political party, aiming to win an election? Broaden your messaging, build coalitions, and prioritize issues that resonate with a wide audience. Recognizing these differences can help you tailor your strategies for maximum impact.

Ultimately, the distinction between interest groups and political parties lies in their scope and ambition. Interest groups are specialists, driving change on specific issues through focused advocacy. Political parties are generalists, seeking to control the levers of power to shape the entire political landscape. Both are essential to a functioning democracy, but their roles are complementary, not interchangeable. By understanding this dynamic, citizens and activists can better navigate the complexities of political engagement and contribute more effectively to the causes they care about.

Understanding Political Party Affiliations: Identity, Ideology, and Influence Explained

You may want to see also

Membership Structure: Parties require formal membership; interest groups often have looser affiliations

One of the most striking differences between political parties and interest groups lies in their membership structures. Political parties typically require formal membership, often involving registration, dues, and active participation in party activities. This structured approach ensures a committed base of supporters who align with the party’s platform and are willing to invest time and resources. For instance, in the United States, joining the Democratic or Republican Party often means signing up through a state-specific process, attending local meetings, and sometimes paying annual fees. This formalization fosters a sense of belonging and accountability, but it can also create barriers to entry for casual supporters.

In contrast, interest groups thrive on looser affiliations, allowing individuals to engage on their own terms. Membership in organizations like the Sierra Club or the National Rifle Association (NRA) often requires little more than a financial contribution or signing up for newsletters. This flexibility enables interest groups to attract a broader and more diverse base of supporters, from passionate activists to passive sympathizers. For example, someone might donate to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) without ever attending a meeting or formally registering as a member. This model prioritizes accessibility over structure, making it easier to mobilize large numbers of people around specific issues.

The implications of these differing structures are significant. Formal party membership fosters a disciplined, cohesive unit capable of coordinating complex political campaigns. However, it can also limit inclusivity, as the requirements may deter those with limited time or resources. Interest groups, with their looser affiliations, excel at rapid mobilization and issue-specific advocacy but may struggle to maintain long-term engagement or a unified voice. For instance, while a political party can rely on its formal members to canvass neighborhoods during an election, an interest group might need to rely on sporadic volunteers or paid staff to achieve similar goals.

Practical considerations for individuals deciding where to invest their political energy should factor in these structural differences. If you’re seeking a structured environment where your efforts contribute to a broad, long-term political agenda, joining a political party might be the better choice. However, if you’re passionate about a specific issue and prefer flexibility in your involvement, an interest group could be more suitable. For example, a climate activist might join the Green Party for its formal platform but also donate to the Environmental Defense Fund for its targeted campaigns.

Ultimately, the membership structure of political parties and interest groups reflects their distinct goals and operational styles. Parties aim to build a sustained, organized movement to win elections and govern, while interest groups focus on influencing policy through targeted advocacy. Understanding these differences can help individuals and organizations strategize more effectively, whether they’re advocating for change or seeking to engage with like-minded people. By recognizing the trade-offs between formal membership and loose affiliation, one can navigate the political landscape with greater clarity and purpose.

Building Iran's Resistance: A Step-by-Step Guide to Forming a Political Party

You may want to see also

Electoral Involvement: Political parties run candidates; interest groups influence elections indirectly

Political parties and interest groups both play pivotal roles in shaping electoral outcomes, but their methods of involvement are fundamentally distinct. While political parties directly participate in elections by fielding candidates, interest groups operate behind the scenes, leveraging influence through advocacy, lobbying, and mobilization. This difference in approach underscores their unique contributions to the democratic process.

Consider the mechanics of electoral involvement. Political parties are the backbone of candidate-centered elections, meticulously selecting, funding, and promoting individuals to represent their platforms. For instance, in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, the Democratic and Republican parties invested billions in campaigns, debates, and advertising to secure their nominees’ victories. Interest groups, on the other hand, focus on shaping the electoral environment rather than competing in it. The National Rifle Association (NRA), for example, does not run candidates but wields significant power by endorsing politicians, funding campaigns, and mobilizing its membership to vote for gun-rights advocates.

The indirect influence of interest groups often manifests through issue-based campaigns and voter education. Take the Sierra Club, an environmental organization that targets specific races by endorsing candidates who align with its green agenda. During the 2018 midterms, the group spent over $4 million on ads and grassroots efforts to support pro-environment candidates, contributing to a wave of victories for Democrats in key districts. This strategy highlights how interest groups can sway elections without ever appearing on the ballot themselves.

However, this indirect approach is not without challenges. Interest groups must navigate legal restrictions, such as campaign finance laws, which limit their ability to coordinate directly with candidates. For example, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 restricts "soft money" contributions, forcing groups like the NRA to operate primarily through Political Action Committees (PACs) or Super PACs. Despite these constraints, interest groups remain potent forces by focusing on long-term relationship-building with policymakers and cultivating public opinion.

In practice, understanding this dynamic is crucial for voters and activists alike. While political parties offer a clear choice between candidates, interest groups provide a lens through which to evaluate those candidates based on specific issues. For instance, a voter concerned about healthcare might look to endorsements from the American Medical Association or Planned Parenthood to guide their decision. By recognizing the distinct roles of parties and interest groups, citizens can engage more strategically in the electoral process, amplifying their voice on the issues that matter most.

NTR's Political Journey: The Day He Entered Andhra Pradesh Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Policy Influence: Interest groups lobby for policies; parties create and implement broader agendas

Interest groups and political parties both seek to shape governance, but their approaches to policy influence diverge sharply. Interest groups operate as specialized advocates, zeroing in on specific issues or sectors. For instance, the American Heart Association lobbies for policies promoting cardiovascular health, while the National Rifle Association focuses on gun rights. Their strength lies in depth, not breadth—they marshal expertise, data, and grassroots support to sway legislators on targeted issues. Political parties, by contrast, craft comprehensive agendas addressing a wide spectrum of issues, from healthcare to foreign policy. While interest groups are like surgeons, precise and focused, parties function as general practitioners, diagnosing and treating the body politic as a whole.

Consider the legislative process as a battlefield. Interest groups deploy lobbyists, campaign contributions, and public pressure to win specific policy battles. For example, the Sierra Club might push for stricter emissions standards, leveraging scientific studies and member activism. Their success hinges on persuading lawmakers to adopt narrow, issue-specific measures. Parties, however, aim to control the entire war. They seek electoral victories to implement broad platforms, such as tax reform or healthcare expansion. A party’s agenda is a mosaic, with each policy piece contributing to a larger vision. While interest groups fight for individual tiles, parties design and assemble the entire picture.

This distinction has practical implications for citizens engaging with the political system. If you’re passionate about a single issue—say, renewable energy—joining an interest group like the Solar Energy Industries Association offers a direct avenue to influence policy. Your efforts will be amplified through focused campaigns and targeted advocacy. However, if you’re concerned about a range of issues and seek systemic change, aligning with a political party provides a broader platform. Parties offer the opportunity to shape not just individual policies but the overarching direction of governance. For instance, voting for a party committed to climate action ensures that renewable energy is part of a larger strategy, not an isolated initiative.

A cautionary note: interest groups, with their narrow focus, can sometimes distort policy priorities. Powerful industries like Big Pharma or Big Tech may wield disproportionate influence, skewing legislation in their favor. Parties, while broader in scope, risk diluting their impact by spreading resources too thin. Striking a balance requires vigilance from both policymakers and citizens. For individuals, diversifying engagement—supporting interest groups while remaining active in party politics—can maximize influence while mitigating risks. Ultimately, understanding these distinct roles empowers citizens to navigate the political landscape strategically, whether advocating for a single cause or championing comprehensive reform.

New York Sheriff's Political Affiliation: Uncovering Party Ties and Influence

You may want to see also

Funding Sources: Parties rely on donations and dues; interest groups often use grants and fees

Political parties and interest groups differ fundamentally in how they secure financial resources, a distinction that shapes their operations and influence. Parties primarily depend on donations from individuals, corporations, and unions, often supplemented by membership dues. These funds fuel election campaigns, party infrastructure, and outreach efforts. Interest groups, on the other hand, frequently tap into grants from foundations, government agencies, or international bodies, alongside membership fees and service charges. This funding model allows them to focus on advocacy, research, and mobilization around specific issues rather than electoral victories.

Consider the mechanics of these funding sources. Political parties often face strict regulations on donation amounts and disclosure requirements, which can limit their financial flexibility. For instance, in the U.S., individual contributions to federal candidates are capped at $3,300 per election cycle. Interest groups, particularly non-profits, may enjoy more leeway, especially when their activities fall under educational or charitable categories. Grants, for example, often require detailed proposals outlining how funds will advance specific goals, such as policy research or community programs. This process demands strategic planning but can provide substantial, sustained support.

The implications of these funding differences are profound. Parties’ reliance on donations ties them closely to donors’ interests, potentially skewing their platforms to favor certain constituencies. Interest groups, funded by grants and fees, can maintain a narrower focus, advocating for specific causes without the pressure of appealing to a broad electorate. For example, an environmental interest group might secure a grant to study climate change impacts, while a political party must balance environmental concerns with economic and social issues to attract diverse voters.

Practical tips for navigating these funding landscapes include diversifying income streams. Parties can explore grassroots fundraising, such as small-dollar donations, to reduce dependence on large contributors. Interest groups should cultivate relationships with grant-making institutions and ensure their proposals align with funders’ priorities. Both entities must remain vigilant about compliance with financial regulations to avoid legal pitfalls. By understanding these funding dynamics, organizations can optimize their resources and maximize their impact in their respective spheres.

Unveiling Ulysses S. Grant's Political Party Affiliation: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Interest groups focus on advocating for specific issues or policies, while political parties aim to gain political power and control government positions.

Interest groups typically have voluntary, issue-specific memberships, whereas political parties are broader organizations with members aligned by a shared ideology or platform.

No, political parties directly run candidates for office and participate in elections, while interest groups primarily influence elections by lobbying, endorsing candidates, or funding campaigns without running candidates themselves.

Political parties are defined by a comprehensive ideology or set of principles, whereas interest groups are often single-issue focused and may not align with a specific ideological framework.

Interest groups rely on lobbying, public campaigns, and litigation to influence policy, while political parties use electoral strategies, legislative processes, and party platforms to shape governance.