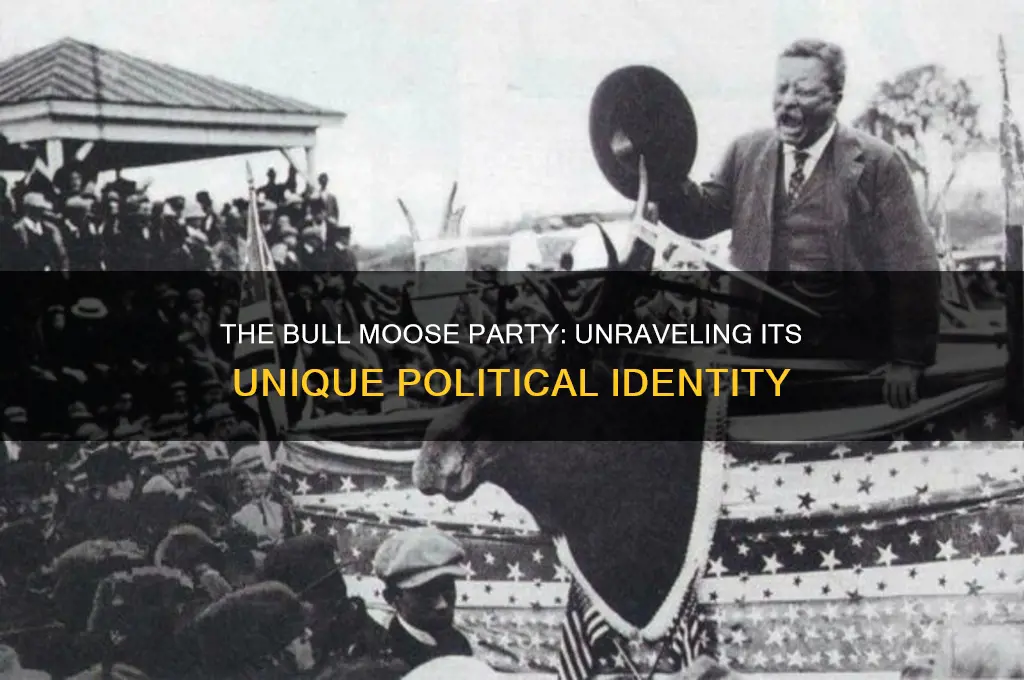

The Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, was a short-lived yet influential political party in the United States, founded in 1912 by former President Theodore Roosevelt. After a falling out with his successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party, Roosevelt championed progressive reforms and ran for president under the Bull Moose banner, named after his famous quote, I'm as strong as a bull moose. The party advocated for social justice, trust-busting, women's suffrage, and conservation, appealing to middle-class voters and reformers. Despite Roosevelt's energetic campaign and a strong third-place finish in the 1912 election, the party disbanded after his defeat, though its progressive ideals left a lasting impact on American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Progressive Party |

| Common Name | Bull Moose Party |

| Founded | 1912 |

| Founder | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Ideology | Progressivism, Social Reform, Conservationism, Trust Busting, Direct Democracy |

| Position | Center to Center-Left |

| Key Policies | - Women's Suffrage - Social Welfare Programs - Regulation of Big Business - Conservation of Natural Resources - Direct Election of Senators - Recall Elections and Initiative Process |

| 1912 Presidential Candidate | Theodore Roosevelt |

| 1912 Election Result | Second place (27.4% of popular vote, 88 electoral votes) |

| Dissolution | 1920 (effectively dissolved after 1916 election) |

| Legacy | Influenced later progressive movements and policies, including the New Deal |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Progressive Platform: Focused on social justice, trust-busting, and labor rights reforms

- Theodore Roosevelt’s Leadership: Founded by Roosevelt after leaving the Republican Party

- Election Impact: Split Republican votes, aiding Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s victory

- Party Symbolism: Named after Roosevelt’s claim to be fit as a bull moose

- Short-Lived Existence: Dissolved after 1912, with members rejoining Republicans or Democrats

Progressive Platform: Focused on social justice, trust-busting, and labor rights reforms

The Bull Moose Party, formally known as the Progressive Party, emerged in 1912 as a bold response to the perceived failures of the major political parties in addressing the pressing issues of the time. At its core, the party championed a progressive platform that prioritized social justice, trust-busting, and labor rights reforms. These principles were not mere campaign slogans but a call to action to dismantle systemic inequalities and corporate monopolies that stifled economic and social progress. By focusing on these areas, the Bull Moose Party sought to empower the working class, protect consumers, and restore fairness to the American economy.

Social justice was a cornerstone of the Progressive Party’s agenda, reflecting a commitment to addressing the disparities faced by marginalized groups. This included advocating for women’s suffrage, civil rights for African Americans, and fair treatment of immigrants. For instance, the party supported the passage of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, and pushed for anti-lynching legislation to combat racial violence. Practical steps included community organizing, public education campaigns, and legislative lobbying to ensure these reforms were not just ideals but actionable policies. The party’s emphasis on social justice was a direct response to the era’s rampant discrimination and inequality, making it a trailblazer in the fight for human rights.

Trust-busting was another critical component of the Bull Moose Party’s platform, targeting the monopolistic practices of large corporations that dominated industries and exploited consumers. Led by figures like Theodore Roosevelt, the party sought to break up these trusts and promote fair competition. This involved strengthening antitrust laws, such as the Sherman Act, and creating regulatory bodies like the Federal Trade Commission to oversee corporate behavior. For businesses, this meant adhering to stricter guidelines to prevent price-fixing and market manipulation. For consumers, it meant lower prices and greater choice. The party’s trust-busting efforts were not just economic policy but a moral stance against the concentration of power in the hands of a few.

Labor rights reforms were equally central to the Progressive Party’s vision, as they recognized the plight of workers in an era of industrialization and exploitation. The party advocated for an eight-hour workday, safer working conditions, and the right to collective bargaining. They also supported minimum wage laws and protections for child laborers, addressing the widespread abuse of young workers in factories. For workers, this meant joining unions without fear of retaliation and demanding fair wages. Employers were urged to prioritize worker well-being over profit margins, a shift that required both legislative action and cultural change. The party’s labor reforms were a direct challenge to the status quo, aiming to create a more equitable balance between capital and labor.

In practice, the Bull Moose Party’s progressive platform was a blueprint for systemic change, offering specific, actionable solutions to the era’s most pressing issues. While the party’s existence was short-lived, its legacy endures in the policies and principles it championed. Social justice, trust-busting, and labor rights reforms remain relevant today, serving as a reminder of the power of political movements to shape a more just and equitable society. By studying the Bull Moose Party’s approach, modern advocates can draw inspiration and strategies for addressing contemporary challenges, ensuring that the fight for progress continues.

Tuesday Night Politics: Unveiling the Winner and Key Takeaways

You may want to see also

Theodore Roosevelt’s Leadership: Founded by Roosevelt after leaving the Republican Party

Theodore Roosevelt's leadership was a catalyst for the creation of the Progressive Party, colloquially known as the Bull Moose Party, in 1912. His decision to leave the Republican Party and establish a new political entity was driven by a deep-seated commitment to progressive reform and a rejection of the conservative policies dominating the GOP at the time. Roosevelt's bold move was not just a personal choice but a strategic effort to realign American politics around issues like trust-busting, labor rights, and social welfare. This party was a direct reflection of his vision for a more equitable and just society, embodying his belief that government should actively address the needs of the common people.

To understand the Bull Moose Party, consider its platform as a blueprint for progressive governance. Roosevelt advocated for a federal income tax, women's suffrage, and stricter regulations on corporations—policies that were radical for their time. For instance, his proposal to recall judicial decisions aimed to curb the power of unelected judges, a move that underscored his commitment to democratic accountability. These ideas were not merely theoretical; they were actionable steps designed to dismantle systemic inequalities. For anyone looking to implement progressive policies today, studying the Bull Moose platform offers a historical framework for addressing contemporary issues like economic disparity and corporate influence.

Roosevelt's leadership style was as distinctive as his policies. He was a master of public engagement, using his charisma and oratory skills to rally support for the Progressive Party. His famous "New Nationalism" speech laid out a vision of a strong federal government working on behalf of the people, a stark contrast to the laissez-faire approach of his Republican opponents. This approach was not without risks; his confrontational style alienated some moderate Republicans, but it also galvanized a passionate base. Leaders today can learn from Roosevelt's ability to balance bold vision with grassroots mobilization, a strategy that remains effective in building political movements.

Comparing the Bull Moose Party to other third-party movements reveals its unique impact. Unlike many third parties that fade into obscurity, the Progressive Party forced major changes within the two-party system. Its influence pushed the Democratic Party, under Woodrow Wilson, to adopt progressive reforms like the Federal Reserve and child labor laws. This demonstrates how a third party, led by a figure as dynamic as Roosevelt, can shape national policy even without winning the presidency. For modern political organizers, this is a lesson in leveraging third-party platforms to drive systemic change.

Finally, the legacy of the Bull Moose Party lies in its embodiment of Roosevelt's leadership principles: courage, conviction, and a relentless focus on the public good. His willingness to challenge the status quo and forge a new path remains a model for leaders facing entrenched opposition. While the party itself was short-lived, its ideas continue to resonate in American politics. For those seeking to effect meaningful change, Roosevelt's example teaches that true leadership often requires breaking from established norms and championing a vision that prioritizes the collective over the individual.

Family Size and Political Affiliation: Exploring Potential Correlations and Trends

You may want to see also

1912 Election Impact: Split Republican votes, aiding Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s victory

The 1912 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, largely due to the emergence of the Progressive or "Bull Moose" Party, led by former President Theodore Roosevelt. This third-party challenge had a profound impact on the electoral landscape, most notably by splitting the Republican vote and paving the way for Democrat Woodrow Wilson's victory. To understand this dynamic, consider the electoral math: in a two-party system, a significant third-party contender can disrupt the balance, siphoning votes from one major party and altering the outcome. In 1912, Roosevelt's Bull Moose Party drew heavily from traditional Republican supporters, leaving incumbent President William Howard Taft with a fragmented base. This division proved fatal for the Republicans, as Wilson secured the presidency with just 41.8% of the popular vote, the lowest winning percentage since Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Analyzing the vote distribution reveals the extent of the split. Roosevelt captured 27.4% of the popular vote, while Taft secured only 23.2%. Had the Republican vote remained unified, even a modest consolidation behind either candidate could have tipped the scales against Wilson. The Bull Moose Party's platform, which championed progressive reforms like trust-busting, labor rights, and women's suffrage, resonated with many traditional Republican voters who felt Taft's administration was too conservative. This ideological overlap created a natural divide within the GOP, as Roosevelt's charismatic appeal and bold agenda attracted both moderate and progressive Republicans, leaving Taft with a diminished and more conservative coalition.

From a strategic perspective, the 1912 election offers a cautionary tale about the risks of party fragmentation. The Bull Moose Party's entry into the race was not merely a spoiler for Taft but a reflection of deeper ideological rifts within the Republican Party. Roosevelt's decision to run as a third-party candidate after losing the GOP nomination to Taft highlighted the growing tension between progressive and conservative wings of the party. This internal conflict not only cost the Republicans the election but also reshaped the party's identity for decades. Wilson's victory, enabled by the split Republican vote, marked the beginning of a Democratic resurgence and underscored the importance of party unity in securing electoral success.

To illustrate the practical implications, consider the electoral college results. Wilson won 435 electoral votes, while Roosevelt and Taft garnered 88 and 8, respectively. In key states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois, the combined Republican and Bull Moose votes exceeded Wilson's totals, suggesting that a unified Republican front could have altered the outcome. This scenario highlights the strategic miscalculation of allowing a third-party challenge to divide the electorate. For modern political strategists, the 1912 election serves as a reminder that ideological purity can come at the cost of electoral viability, and that managing internal party differences is crucial to avoiding self-inflicted defeats.

In conclusion, the 1912 election's impact on Woodrow Wilson's victory was decisively shaped by the Bull Moose Party's role in splitting the Republican vote. This event not only handed the presidency to the Democrats but also redefined the political landscape, accelerating the rise of progressivism and reshaping party alignments. For those studying electoral dynamics, the lesson is clear: in a closely contested race, the emergence of a third party can be a game-changer, particularly when it fractures the base of one of the major parties. The Bull Moose Party's legacy thus remains a powerful example of how internal divisions can have far-reaching consequences, both for individual elections and the broader trajectory of American politics.

Unraveling the Historical Roots: Which Political Party Started Slavery?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

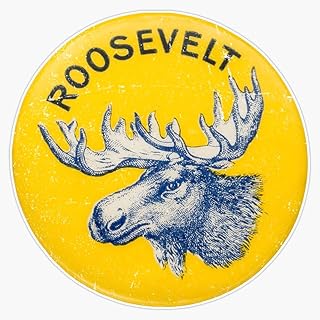

Party Symbolism: Named after Roosevelt’s claim to be fit as a bull moose

The Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, owes its evocative nickname to Theodore Roosevelt’s bold declaration during the 1912 campaign. After losing the Republican nomination to William Howard Taft, Roosevelt announced his candidacy on the Progressive ticket, proclaiming, "I feel as fit as a bull moose." This phrase became the party’s unofficial symbol, encapsulating its core identity. The bull moose, a creature of strength, resilience, and independence, mirrored Roosevelt’s vision for a party that would challenge the status quo and champion reform. This symbolism was not merely a catchy slogan but a strategic choice to differentiate the Progressives from the established parties, positioning them as a force of vitality and determination.

Analyzing the symbolism reveals its dual purpose: to embody Roosevelt’s personal brand and to communicate the party’s values. The bull moose, native to North America, represented a uniquely American spirit of rugged individualism and tenacity. By aligning himself and his party with this animal, Roosevelt sought to appeal to voters who felt disillusioned with the corruption and inertia of traditional politics. The imagery also served as a visual shorthand for the party’s platform, which emphasized trust-busting, conservation, and social justice. In a time before mass media, such symbolism was a powerful tool to convey complex ideas quickly and memorably.

To understand the impact of this symbolism, consider its practical application in campaign materials. Posters, buttons, and speeches frequently featured the bull moose, often depicted charging forward, symbolizing progress and momentum. For instance, a popular campaign button from 1912 bore the image of a bull moose with the slogan, "Vote for Teddy and the Bull Moose." This tangible representation of the party’s ethos helped galvanize supporters, particularly among younger voters and those in rural areas who identified with the animal’s strength and independence. Even today, political strategists study this example as a masterclass in using symbolism to build a brand.

However, the bull moose symbolism was not without its limitations. While it effectively captured Roosevelt’s charisma and the party’s energy, it risked oversimplifying the Progressive agenda. Critics argued that the focus on Roosevelt’s persona and the bull moose imagery overshadowed the nuanced policies the party advocated. For instance, the party’s push for women’s suffrage, labor rights, and environmental conservation were complex issues that required more than a symbol to fully articulate. This tension highlights the challenge of balancing memorable symbolism with substantive policy communication.

In conclusion, the Bull Moose Party’s symbolism remains a fascinating case study in political branding. By naming the party after Roosevelt’s claim to be "fit as a bull moose," the Progressives created an enduring image that resonated with voters and distinguished them from their opponents. While the symbolism had its drawbacks, it succeeded in its primary goal: to inspire and mobilize a coalition of reformers. For modern political parties, the lesson is clear: symbolism can be a powerful tool, but it must be paired with clear messaging and actionable policies to achieve lasting impact.

Alan Alda's Political Party: Uncovering His Affiliation and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Short-Lived Existence: Dissolved after 1912, with members rejoining Republicans or Democrats

The Bull Moose Party, formally known as the Progressive Party, burst onto the political scene in 1912 with Theodore Roosevelt at its helm. Despite its energetic start and ambitious platform, the party’s existence was fleeting, dissolving shortly after the 1912 election. This dissolution wasn’t merely a fade into obscurity; it was a strategic realignment as members returned to their roots in the Republican or Democratic parties. Understanding this short-lived existence requires examining the party’s structural vulnerabilities, the post-election landscape, and the pragmatic choices of its members.

Consider the party’s foundation: it was built around Roosevelt’s charisma and progressive ideals rather than a robust organizational framework. Unlike established parties with deep-rooted local and state networks, the Bull Moose Party relied heavily on Roosevelt’s personal appeal. When the 1912 election ended with Roosevelt’s defeat and Woodrow Wilson’s victory, the party lost its central unifying figure. Without a strong infrastructure or a clear successor, the party’s cohesion crumbled. Members faced a stark choice: remain loyal to a fading movement or rejoin parties with greater resources and influence.

The post-election environment further accelerated the party’s dissolution. The 1912 election fractured the Republican Party, with Roosevelt’s third-party bid splitting the conservative vote and handing the presidency to the Democrats. For Bull Moose members, this outcome underscored the limitations of their party’s impact. Many progressives realized that their goals—such as trust-busting, labor rights, and social welfare—could be pursued more effectively within the established parties. Rejoining the Republicans or Democrats offered a practical pathway to influence policy without the risks of a third-party gamble.

Pragmatism played a decisive role in this realignment. Political careers and progressive ideals often clashed within the Bull Moose Party’s fragile structure. For instance, members like Gifford Pinchot, a prominent conservationist, returned to the Republican Party to continue advocating for environmental reforms. Others, like Robert La Follette, shifted focus to building progressive coalitions within the Democratic Party. This strategic retreat wasn’t a failure but a recalibration, as former Bull Moose members carried their progressive agenda into more fertile political ground.

In retrospect, the Bull Moose Party’s dissolution was less a collapse than a redistribution of its energy and ideas. Its short-lived existence highlights the challenges of sustaining a third party in a two-party system, where structural barriers and electoral realities often dictate survival. For modern political movements, the lesson is clear: charisma and ideals alone are insufficient. Building a durable party requires organizational resilience and a clear path to power. The Bull Moose Party’s legacy endures not in its longevity but in the progressive reforms its members achieved after rejoining the political mainstream.

Eisenhower's Political Success: Leadership, Strategy, and Broad Appeal Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, was a reform-oriented political party in the United States.

The Bull Moose Party was led by former President Theodore Roosevelt, who ran as its presidential candidate in the 1912 election.

The party advocated for progressive reforms, including trust-busting, women's suffrage, labor rights, environmental conservation, and government transparency.

The name "Bull Moose" came from Theodore Roosevelt's remark during the 1912 campaign that he felt "as strong as a bull moose," which became a popular nickname for the party.

The Bull Moose Party finished second in the 1912 presidential election, with Theodore Roosevelt winning 27% of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes, but ultimately losing to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

![The Sons of the Sires A History of the Rise, Progress, and Destiny of the American Party, and Its Probable Influence on the Next Presidential Election 1855 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)