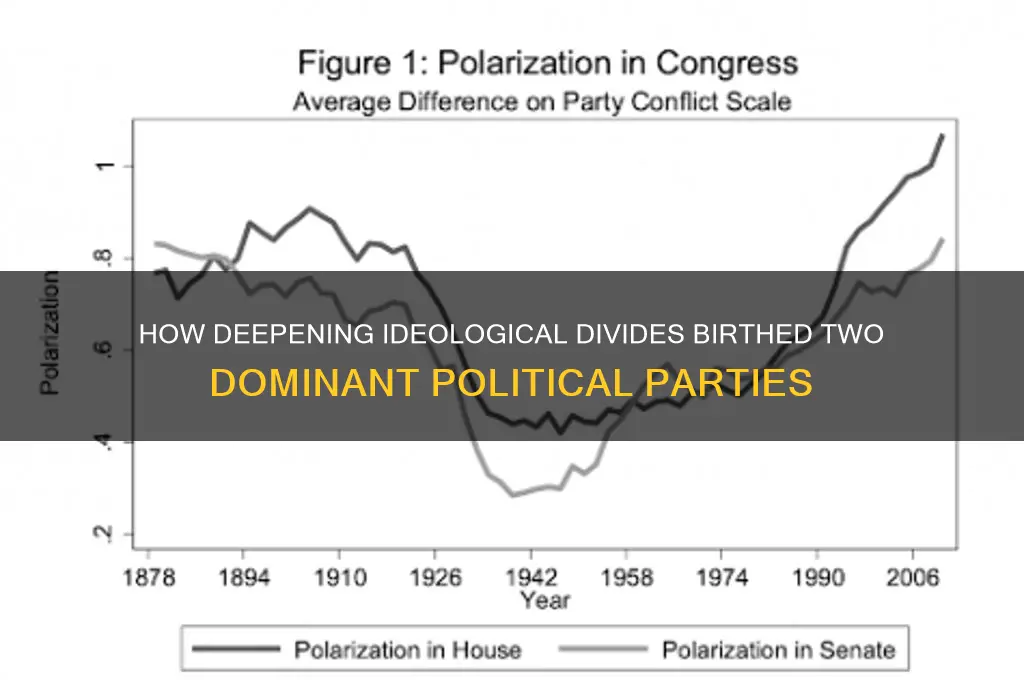

The emergence of two dominant political parties in many democratic systems, such as the United States, can be traced back to fundamental issues and divisions that arose during the nation's formative years. In the U.S., the Federalist and Anti-Federalist factions of the late 18th century laid the groundwork for the eventual rise of the Democratic-Republican and Federalist parties, which later evolved into the modern Democratic and Republican parties. Central to this development were debates over the role of the federal government, states' rights, economic policies, and the interpretation of the Constitution. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government and a market-driven economy, while the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, emphasized states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal role. These ideological differences, coupled with personal rivalries and regional interests, solidified the two-party system, as voters and politicians coalesced around these competing visions for the nation's future.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Context | Emergence of political parties often tied to societal changes, independence, or constitutional developments. |

| Ideological Differences | Parties form around contrasting beliefs (e.g., federalism vs. anti-federalism, conservatism vs. liberalism). |

| Economic Interests | Divisions based on economic policies, such as agrarian vs. industrial interests or free trade vs. protectionism. |

| Regional Tensions | Geographic or cultural differences (e.g., North vs. South in the U.S. during the 19th century). |

| Leadership and Personalities | Charismatic leaders or influential figures drive party formation (e.g., Jefferson vs. Hamilton). |

| Electoral Systems | First-past-the-post or winner-takes-all systems encourage two-party dominance. |

| Social and Cultural Issues | Parties emerge around contentious social issues (e.g., slavery, civil rights, or immigration). |

| Institutional Factors | Constitutional structures or political institutions favor a two-party system (e.g., U.S. Constitution). |

| Media and Public Discourse | Media polarization and public debate contribute to the solidification of two dominant parties. |

| Global Influences | International events or ideologies (e.g., Cold War, globalization) shape party identities. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Policies: Disagreements over tariffs, banking, and economic roles split early American politicians

- States' Rights: Debates on federal vs. state authority created ideological divides

- Foreign Policy: Pro-French vs. pro-British stances fueled partisan differences

- Interpretation of Constitution: Strict vs. loose construction views shaped party formations

- Leadership Rivalries: Personal conflicts between leaders like Hamilton and Jefferson intensified polarization

Economic Policies: Disagreements over tariffs, banking, and economic roles split early American politicians

The early United States, still finding its footing after the Revolutionary War, was a nation divided not just by geography but by competing visions of its economic future. These divisions, centered on tariffs, banking, and the proper role of the federal government in the economy, became the fault lines along which the first political parties emerged.

At the heart of the debate lay tariffs. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, championed protective tariffs to nurture fledgling American industries, shield them from foreign competition, and generate revenue for the young nation. Thomas Jefferson and his agrarian supporters, however, viewed tariffs as a burden on the South, which relied heavily on agricultural exports and imported manufactured goods. This clash of interests, pitting industrial North against agrarian South, became a defining feature of early American politics.

The question of a national bank further exacerbated these tensions. Hamilton advocated for a strong central bank to stabilize the currency, manage debt, and facilitate commerce. Jefferson, a staunch states' rights advocate, saw the bank as a dangerous concentration of power, favoring the financial elite at the expense of the common man. The bitter debate over the First Bank of the United States, established in 1791, became a rallying cry for those who feared the encroachment of federal authority on individual liberties.

The differing economic philosophies of Hamilton and Jefferson crystallized into distinct political factions. Hamilton's Federalists, largely urban merchants and industrialists, favored a strong central government and an economy driven by manufacturing and commerce. Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans, predominantly farmers and planters, championed states' rights, limited government, and an agrarian-based economy. These competing visions, fueled by disagreements over tariffs and banking, solidified the divide between the two emerging parties.

The impact of these economic disagreements extended far beyond policy debates. They shaped the very identity of the young nation, influencing regional alliances, electoral strategies, and the course of American history. The struggle between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans laid the groundwork for the two-party system that continues to characterize American politics today, a system born from the clash of economic ideologies in the early republic.

Why Does Facebook Categorize Me as a Political Party?

You may want to see also

States' Rights: Debates on federal vs. state authority created ideological divides

The tension between federal and state authority has long been a cornerstone of American political discourse, shaping the emergence and evolution of its two-party system. At the heart of this debate lies the question: Who holds the ultimate power—the national government or individual states? This ideological divide crystallized in the early years of the republic, as leaders grappled with the interpretation of the Constitution and the balance of power it sought to establish. The Federalist Party, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, championed a strong central government, viewing it as essential for economic stability and national unity. In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, spearheaded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for states’ rights, fearing that unchecked federal authority would undermine local autonomy and individual liberties.

Consider the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, a prime example of this conflict. Federalists, in control of the national government, enacted these laws to suppress dissent and strengthen federal power. The Acts allowed the president to deport non-citizens deemed dangerous and criminalized criticism of the government. States like Kentucky and Virginia responded with the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, penned by Jefferson and Madison, which argued that states had the right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. This clash highlighted the deep ideological rift: Federalists saw the Acts as necessary for national security, while Democratic-Republicans viewed them as an overreach of federal authority and a threat to free speech.

To understand the practical implications of this divide, examine the economic policies of the early 19th century. Federalists pushed for a national bank and protective tariffs to foster industrial growth, policies that benefited northern states but were resisted by agrarian southern states. Democratic-Republicans, rooted in the South, argued that such measures infringed on states’ rights and disproportionately benefited certain regions. This economic disparity fueled the ideological split, as states began to align with parties that best represented their local interests. For instance, the Nullification Crisis of 1832, where South Carolina declared federal tariffs void, underscored the enduring tension between federal authority and state sovereignty.

A persuasive argument can be made that the states’ rights debate remains relevant today, though its manifestations have evolved. Modern issues like healthcare, education, and environmental regulation often pit federal mandates against state autonomy. For example, the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion was implemented differently across states, with some embracing it and others resisting on grounds of fiscal and ideological independence. This contemporary dynamic mirrors the historical divide, proving that the struggle between federal and state authority is not a relic of the past but a living, breathing aspect of American politics.

In navigating this complex issue, it’s instructive to adopt a comparative lens. While federal authority ensures uniformity and national cohesion, state autonomy fosters innovation and responsiveness to local needs. Striking a balance requires recognizing the legitimacy of both perspectives. Policymakers and citizens alike must engage in dialogue that respects the principles of federalism while addressing the practical challenges of a diverse and decentralized nation. By doing so, they can honor the foundational debates that gave rise to America’s two-party system while adapting to the demands of the 21st century.

Kim Conway's Political Party Affiliation in Billerica, MA Explained

You may want to see also

Foreign Policy: Pro-French vs. pro-British stances fueled partisan differences

The late 18th and early 19th centuries in the United States were marked by a deepening divide over foreign policy, particularly regarding allegiances to France and Britain. This rift, rooted in differing visions of America’s role in the world, became a cornerstone of the emerging two-party system. The Federalist Party, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, favored strong ties with Britain, emphasizing economic stability and commercial interests. In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, championed by Thomas Jefferson, leaned toward France, aligning with its revolutionary ideals and agrarian values. This pro-British versus pro-French stance was not merely a diplomatic preference but a reflection of deeper ideological and economic divides that shaped American politics.

Consider the XYZ Affair of 1797–1798, a diplomatic scandal that crystallized these partisan differences. When French agents demanded bribes from American diplomats, Federalists seized the opportunity to rally public sentiment against France, advocating for a pro-British alignment. Democratic-Republicans, however, viewed the incident as a Federalist ploy to undermine France and strengthen ties with Britain. This event illustrates how foreign policy became a tool for domestic political mobilization, with each party leveraging international issues to solidify its base. The Federalists’ pro-British stance was tied to their vision of a strong central government and a mercantile economy, while the Democratic-Republicans’ pro-French leanings reflected their commitment to states’ rights and agrarian democracy.

To understand the practical implications of these stances, examine the economic policies of the era. Federalists pushed for a national bank and tariffs to protect American industries, policies that aligned with British economic models. Democratic-Republicans, on the other hand, opposed these measures, fearing they would concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a few, much like the British system they had fought to escape. This economic divide was directly tied to foreign policy: Federalists saw Britain as a model for industrial growth, while Democratic-Republicans viewed France’s agrarian society as more compatible with American ideals. For modern readers, this dynamic underscores the importance of aligning foreign policy with domestic economic goals, a lesson still relevant in today’s globalized world.

A comparative analysis reveals how these foreign policy stances influenced party identities. Federalists, with their pro-British leanings, were often portrayed as elitist and monarchist, while Democratic-Republicans were seen as champions of the common man and democratic ideals. This framing was not accidental; both parties used foreign policy to define themselves in opposition to one another. For instance, Federalist support for the Jay Treaty (1794), which resolved lingering issues with Britain but alienated France, became a rallying cry for Democratic-Republicans, who accused Federalists of betraying American independence. Conversely, Democratic-Republican opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), which targeted French sympathizers, solidified their image as defenders of liberty.

In conclusion, the pro-French versus pro-British divide was more than a foreign policy debate; it was a battle over the soul of the young nation. By examining specific events like the XYZ Affair and policies like the Jay Treaty, we see how international allegiances became proxies for domestic ideological struggles. This historical example offers a cautionary tale: when foreign policy becomes deeply partisan, it risks undermining national unity. For contemporary policymakers, the lesson is clear: foreign policy should be crafted with an eye toward bridging domestic divides, not exacerbating them. By studying this period, we gain insights into how international relations can shape—and be shaped by—partisan politics, a dynamic that continues to play out in modern American political discourse.

Exploring the Political Structure and Governance of the Karankawa Tribe

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Interpretation of Constitution: Strict vs. loose construction views shaped party formations

The interpretation of the U.S. Constitution has been a cornerstone of American political discourse, with strict and loose constructionist views fundamentally shaping the emergence of the nation’s two-party system. Strict constructionists, exemplified by the Federalist Party in the late 18th century, advocated for a narrow reading of the Constitution, emphasizing the importance of adhering closely to its explicit text. This approach often favored a strong central government, as seen in Alexander Hamilton’s financial policies, which aimed to consolidate federal power through measures like the national bank. In contrast, loose constructionists, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party, argued for a more flexible interpretation, allowing the Constitution to adapt to changing circumstances. This perspective championed states’ rights and limited federal authority, as evidenced by Jefferson’s opposition to Hamilton’s economic plans.

These divergent interpretations were not merely academic debates but had tangible political consequences. The Federalist Party’s strict constructionist stance aligned with their vision of a robust, centralized government capable of fostering economic growth and national unity. Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans’ loose constructionist view resonated with agrarian interests and those wary of federal overreach. This ideological split crystallized during debates over issues like the Alien and Sedition Acts, where Federalists supported broad federal powers, and Democratic-Republicans decried them as unconstitutional. The clash between these interpretations laid the groundwork for the two-party system, as each side rallied supporters around their distinct visions of governance.

To understand the practical implications, consider the debate over the Necessary and Proper Clause (Article I, Section 8). Strict constructionists argued it should only permit powers explicitly granted in the Constitution, while loose constructionists saw it as a tool for addressing unforeseen challenges. This disagreement directly influenced policy decisions, such as the creation of the national bank, which strict constructionists viewed as unconstitutional but loose constructionists deemed essential for economic stability. Such disputes highlight how constitutional interpretation became a rallying cry for political factions, solidifying party identities.

A cautionary note: while strict and loose constructionism provided clear ideological frameworks, they also risked oversimplifying complex issues. For instance, strict constructionists often struggled to address emerging national challenges, such as industrialization, without expanding federal powers. Conversely, loose constructionists sometimes justified expansive government actions that undermined states’ rights. This tension underscores the need for balance in constitutional interpretation, a lesson modern political parties continue to grapple with.

In conclusion, the strict versus loose constructionist debate was not just a legal argument but a political catalyst. It framed the early divisions between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, shaping their policies, alliances, and ultimately, the two-party system. By examining this historical dynamic, we gain insight into how constitutional interpretation remains a driving force in American politics, influencing party formations and policy debates to this day.

Strategic Spots: Where to Display Political Stickers Effectively

You may want to see also

Leadership Rivalries: Personal conflicts between leaders like Hamilton and Jefferson intensified polarization

The bitter rivalry between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson exemplifies how personal conflicts among leaders can catalyze political polarization. Their clashing visions for America’s future—Hamilton’s federalist, industrial emphasis versus Jefferson’s agrarian, states’ rights ideal—were not merely policy disagreements but deeply personal feuds. Hamilton’s sharp critiques of Jefferson’s character and Jefferson’s whispered campaigns against Hamilton’s alleged monarchist tendencies transformed their rivalry into a public spectacle. This dynamic illustrates how leadership animosity can overshadow policy debates, forcing followers to choose sides based on loyalty rather than merit.

Consider the mechanics of their conflict: Hamilton’s *Federalist Papers* and Jefferson’s *Kentucky Resolutions* were not just intellectual exercises but weapons in a war of ideas. Their disagreements over the national bank, debt assumption, and foreign policy were amplified by their mutual disdain. For instance, Hamilton’s accusation that Jefferson was “an atheist in religion and a fanatic in politics” was not a neutral critique but a calculated attack designed to alienate Jefferson from religious voters. Such tactics hardened divisions, turning policy differences into moral judgments.

To understand the impact, imagine a modern workplace where two executives publicly undermine each other. Employees, forced to align with one camp or the other, lose sight of shared goals. Similarly, Hamilton and Jefferson’s followers became entrenched in their camps, forming the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. This polarization was not inevitable; it was accelerated by their refusal to collaborate or compromise. Their rivalry became a template for future political conflicts, where personal animosity trumps collective problem-solving.

Practical takeaway: Leaders must recognize that their interpersonal conflicts have systemic consequences. In organizations or governments, fostering a culture of constructive disagreement—where ideas, not individuals, are attacked—can mitigate polarization. For instance, implementing structured debate formats or mediation processes can help depersonalize conflicts. Conversely, allowing rivalries to fester risks creating factions that prioritize loyalty over results, as seen in the Hamilton-Jefferson era.

In conclusion, the Hamilton-Jefferson rivalry was not just a historical footnote but a cautionary tale about the dangers of leadership conflicts. Their inability to separate personal animosity from policy debates deepened America’s political divide, setting a precedent for partisan polarization. By studying their example, modern leaders can learn to manage disagreements without fracturing their constituencies—a lesson as relevant today as it was in the early Republic.

John Delaney's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Membership

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The primary issues were economic policies, particularly the debate over Alexander Hamilton's financial plans, including the national bank and assumption of state debts, which divided Federalists (supporters) and Anti-Federalists (opponents).

The Federalists supported a strong central government and the ratification of the Constitution, while the Anti-Federalists (later Democratic-Republicans) favored states' rights and initially opposed the Constitution, leading to a partisan divide.

Foreign policy, especially the debate over alignment with France or Britain during the French Revolution, deepened the rift between Federalists (pro-British) and Democratic-Republicans (pro-French), solidifying the two-party system.