Political parties are fundamental organizations within democratic systems, serving as intermediaries between the government and the public. Their structure typically consists of several key components: a leadership hierarchy, including party chairs, secretaries, and spokespersons; a central committee or executive board that makes strategic decisions; grassroots organizations such as local chapters or branches to mobilize supporters; and a membership base that participates in party activities, fundraising, and elections. Additionally, many parties have affiliated youth wings, think tanks, or special interest groups to broaden their appeal and influence. This hierarchical yet decentralized structure allows political parties to coordinate efforts, formulate policies, and compete effectively in elections while maintaining connections to diverse constituencies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Leadership | Centralized figure (e.g., party chair, president) or collective leadership |

| Hierarchy | Multi-tiered structure: National, State/Regional, Local levels |

| Membership | Voluntary participation; members pay dues, vote in primaries, and campaign |

| Decision-Making | Top-down or democratic (e.g., voting by members or delegates) |

| Funding | Donations, membership fees, government grants, and fundraising events |

| Ideology | Core principles guiding policies (e.g., conservatism, liberalism, socialism) |

| Organization | Formal committees, wings (e.g., youth, women), and specialized departments |

| Communication | Use of media, social platforms, and party publications for messaging |

| Elections | Candidate selection through primaries, caucuses, or internal voting |

| Alliances | Coalitions with other parties or interest groups for electoral gains |

| Accountability | Internal checks, external scrutiny, and adherence to party constitution |

| Grassroots Engagement | Local chapters, community outreach, and volunteer networks |

| Policy Formation | Think tanks, policy committees, and expert consultations |

| International Affiliation | Alignment with global party organizations (e.g., Socialist International) |

| Technology Use | Digital tools for mobilization, fundraising, and voter outreach |

Explore related products

$1.99 $24.95

$15.97 $21.95

What You'll Learn

- Organizational Hierarchy: Leadership roles, committees, and local chapters define the party's internal structure

- Membership Systems: Recruitment, dues, and participation levels shape party engagement and influence

- Decision-Making Processes: Methods for policy formation, candidate selection, and strategic planning

- Funding Mechanisms: Sources of revenue, donor networks, and financial management within the party

- Ideological Alignment: Core principles, platforms, and how they guide party actions and policies

Organizational Hierarchy: Leadership roles, committees, and local chapters define the party's internal structure

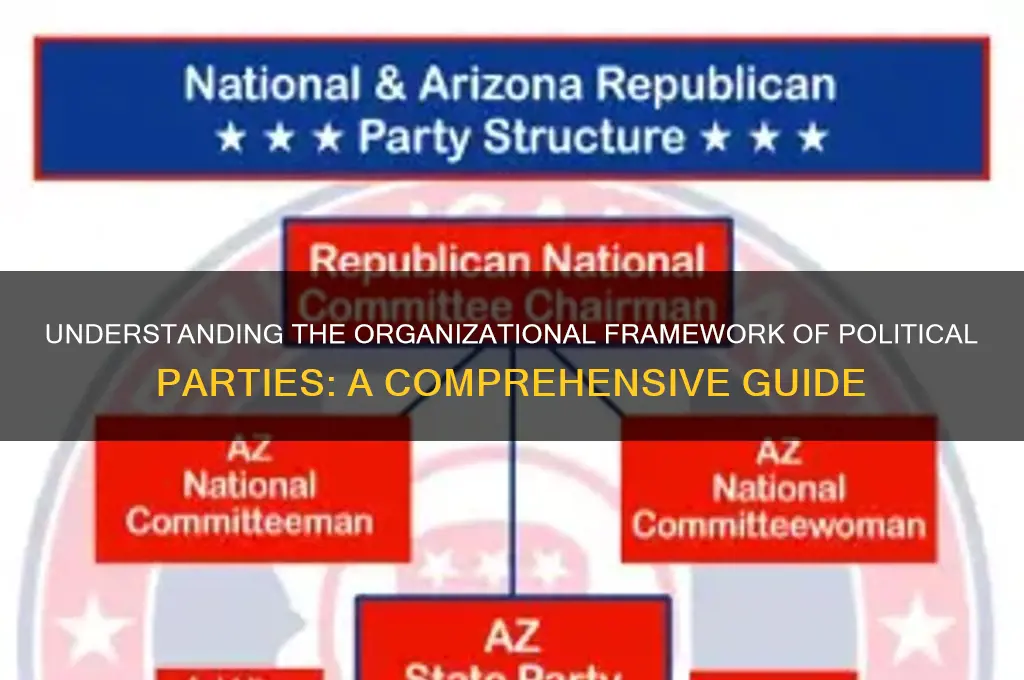

Political parties are not monolithic entities but complex organisms with distinct internal structures that ensure their functionality and effectiveness. At the heart of this structure lies the organizational hierarchy, a framework that delineates leadership roles, committees, and local chapters. This hierarchy is critical for decision-making, resource allocation, and grassroots engagement, ensuring the party operates cohesively across various levels. Without a clear organizational structure, parties risk fragmentation, inefficiency, and a disconnect between leadership and the base.

Consider the leadership roles as the backbone of a political party. These positions—such as party chair, treasurer, and secretary—are typically filled by individuals with strategic vision and managerial skills. For instance, the party chair often serves as the public face of the organization, while the treasurer manages finances, ensuring compliance with legal and ethical standards. These roles are not merely ceremonial; they require a deep understanding of the party’s ideology, the ability to navigate internal politics, and the skill to mobilize resources effectively. In the Democratic Party of the United States, the chair plays a pivotal role in fundraising and coordinating national campaigns, while in the Conservative Party of the United Kingdom, the leader is often the prime ministerial candidate, blending internal party management with external governance responsibilities.

Below the leadership tier, committees form the operational engine of the party. These specialized groups focus on areas like policy development, campaign strategy, and outreach. For example, a policy committee might draft the party’s stance on healthcare, while a finance committee ensures sufficient funds for election campaigns. Committees are often staffed by volunteers or appointed members, providing a platform for diverse voices within the party. In Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the Federal Executive Committee oversees key decisions, while local committees handle regional issues, demonstrating how committees can bridge national and local priorities.

The local chapters are where the party’s ideology and policies take root in communities. These chapters, often organized by district or municipality, serve as the party’s eyes and ears on the ground. They mobilize voters, organize events, and gather feedback from constituents. For instance, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India boasts over 15,000 local units, each playing a crucial role in the party’s nationwide success. Local chapters also act as incubators for future leaders, providing hands-on experience in political organizing. However, maintaining alignment between local chapters and national leadership can be challenging, requiring clear communication channels and shared goals.

A well-structured organizational hierarchy is not just about assigning roles; it’s about fostering collaboration and accountability. Leadership must empower committees to innovate while ensuring their actions align with the party’s core values. Similarly, local chapters need autonomy to address regional concerns but must remain integrated into the broader party strategy. For example, the Labour Party in the UK has faced challenges when local chapters pursued policies at odds with national leadership, highlighting the need for balance. Parties that strike this balance—like Canada’s Liberal Party, which combines strong central leadership with active local engagement—tend to thrive in diverse political landscapes.

In practice, building an effective organizational hierarchy requires intentional design and continuous evaluation. Parties should conduct regular audits of their structure, ensuring roles are clearly defined and resources are allocated efficiently. Training programs for leaders and committee members can enhance their skills, while digital tools can improve communication between national and local levels. For instance, the Democratic Party in the U.S. has invested in platforms like VoteBuilder to streamline data sharing between national and local chapters. By prioritizing adaptability and inclusivity, political parties can create hierarchies that not only sustain their operations but also drive meaningful change.

How to Identify Your Candidate's Political Party Affiliation Easily

You may want to see also

Membership Systems: Recruitment, dues, and participation levels shape party engagement and influence

Political parties thrive on their membership base, and the systems they employ to recruit, retain, and engage members are critical to their success. Recruitment strategies vary widely, from grassroots door-knocking campaigns to digital outreach via social media and email. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States often leverages volunteer networks and community events, while the Conservative Party in the UK has historically relied on local associations and personal invitations. Effective recruitment targets diverse demographics, ensuring the party reflects the broader electorate. A successful recruitment drive not only increases numbers but also fosters a sense of belonging, turning passive supporters into active participants.

Once recruited, members are often required to pay dues, which serve as both a financial lifeline for the party and a commitment mechanism. Dues can range from nominal amounts, such as $10 annually for local chapters, to hundreds of dollars for elite memberships offering exclusive benefits. For example, the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) charges members a percentage of their income, scaling dues based on earnings. This model ensures affordability for lower-income members while maximizing contributions from wealthier ones. However, high dues can deter potential members, so parties must balance financial needs with inclusivity. Dues also symbolize membership value, encouraging individuals to view their contribution as an investment in the party’s mission.

Participation levels are the lifeblood of party engagement, determining how deeply members involve themselves in activities like campaigning, policy development, or leadership roles. Parties often use tiered participation models, where members can choose their level of involvement based on time and interest. For instance, the Labour Party in the UK categorizes members into "standard," "affiliated," and "registered supporter" levels, each with distinct rights and responsibilities. Encouraging participation requires clear pathways for involvement, such as training programs, mentorship schemes, or recognition systems. High participation not only strengthens the party’s operational capacity but also amplifies its influence in elections and policy debates.

The interplay between recruitment, dues, and participation levels creates a feedback loop that shapes party engagement and influence. A well-designed membership system attracts a broad and committed base, generates sustainable funding, and fosters active involvement. Conversely, a poorly structured system risks alienating members, stifling growth, and limiting impact. For example, the decline of traditional membership-based parties in Europe has been linked to rigid structures that fail to adapt to modern expectations. Parties must continually evaluate and innovate their membership systems, ensuring they remain accessible, rewarding, and aligned with members’ values and aspirations.

In practice, parties can enhance their membership systems by adopting data-driven approaches, such as analyzing member demographics to tailor recruitment efforts or using surveys to understand participation barriers. Offering flexible dues options, like monthly subscriptions or pay-what-you-can models, can broaden appeal. Additionally, leveraging technology to create virtual participation opportunities—such as online policy forums or remote volunteering—can engage members who face geographic or time constraints. By prioritizing inclusivity, transparency, and adaptability, parties can build membership systems that not only sustain their operations but also amplify their influence in the political landscape.

Understanding the Core Mission: Primary Goals of Political Parties Explained

You may want to see also

Decision-Making Processes: Methods for policy formation, candidate selection, and strategic planning

Political parties are complex organisms, and their decision-making processes are the lifeblood that sustains their operations. At the heart of these processes lie three critical functions: policy formation, candidate selection, and strategic planning. Each of these functions demands distinct methods, often tailored to the party’s ideology, size, and context. For instance, while some parties rely on centralized leadership for swift decision-making, others embrace decentralized models to foster inclusivity and grassroots engagement. Understanding these methods reveals how parties navigate the delicate balance between unity and diversity, efficiency and deliberation.

Consider policy formation, the backbone of a party’s identity. One common method is the committee-based approach, where specialized groups of experts, members, or delegates draft and refine policies. The Labour Party in the UK, for example, uses its National Policy Forum to engage members in policy development, ensuring alignment with grassroots priorities. In contrast, top-down models are prevalent in parties with strong leadership, such as the Republican Party in the U.S., where key figures like the party chair or presidential nominee often drive policy agendas. A third method, consensus-building through conferences, is seen in Germany’s Christian Democratic Union, where annual party conferences allow for open debate and voting on policy proposals. Each method has trade-offs: committees foster inclusivity but can be slow, top-down approaches ensure coherence but risk alienating members, and conferences promote democracy but may lack focus.

Candidate selection is another critical process, often determining a party’s electoral success. Primary elections, widely used in the U.S., empower registered party members or voters to choose candidates, as seen in the Democratic and Republican primaries. This method enhances legitimacy but can be costly and divisive. In contrast, caucuses, employed by some U.S. states, involve local party meetings where members discuss and vote for candidates, fostering deeper engagement but limiting participation due to time constraints. Centralized selection, common in parliamentary systems like India’s Bharatiya Janata Party, relies on party leadership to handpick candidates, ensuring loyalty but risking public perception of elitism. A hybrid approach, such as shortlisting by committees followed by member voting, is used by the UK’s Conservative Party, balancing control with democratic input.

Strategic planning, the third pillar, requires methods that align short-term tactics with long-term goals. Scenario planning, popularized by parties like Canada’s Liberal Party, involves envisioning multiple future outcomes and preparing responses, ensuring adaptability in volatile political landscapes. Data-driven strategies, increasingly common in modern campaigns, rely on analytics to target voters and allocate resources efficiently, as demonstrated by the Obama campaigns in 2008 and 2012. Coalition-building frameworks, essential for parties in multi-party systems like Israel’s, focus on identifying compatible partners and negotiating shared agendas. Each method demands specific resources: scenario planning requires foresight and creativity, data-driven strategies need robust infrastructure, and coalition-building hinges on negotiation skills.

In practice, parties often blend these methods, tailoring them to their unique needs. For instance, a small, ideologically driven party might prioritize consensus-based policy formation and grassroots candidate selection, while a dominant party in a two-party system may favor centralized decision-making for efficiency. The key lies in aligning methods with the party’s structure, values, and goals. Parties must also remain agile, adapting their processes to evolving political landscapes, technological advancements, and member expectations. By mastering these decision-making methods, political parties can navigate complexity, build cohesion, and achieve their objectives effectively.

Curtis Sliwa's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Funding Mechanisms: Sources of revenue, donor networks, and financial management within the party

Political parties, much like any large-scale organization, require substantial financial resources to operate effectively. Funding mechanisms are the lifeblood of these entities, enabling them to run campaigns, mobilize supporters, and maintain their organizational structures. The sources of revenue for political parties are diverse, ranging from membership fees and small donations to large contributions from wealthy individuals and corporations. In many countries, public funding also plays a significant role, providing parties with a stable financial base while reducing their dependence on private donors. Understanding these funding mechanisms is crucial, as they not only shape the financial health of a party but also influence its policies, strategies, and independence.

One of the most critical aspects of funding mechanisms is the role of donor networks. These networks often consist of individuals, businesses, and interest groups with aligned ideological or economic interests. For instance, in the United States, political action committees (PACs) and super PACs serve as conduits for funneling large sums of money into campaigns, often from corporate or union sources. In contrast, European parties frequently rely on a mix of public funding and membership dues, which fosters broader grassroots support. The composition of a party’s donor network can reveal much about its priorities and allegiances. Parties must carefully navigate these relationships to avoid perceptions of undue influence, which can erode public trust and legitimacy.

Effective financial management is another cornerstone of a party’s funding mechanisms. This involves not only raising funds but also allocating them strategically to maximize impact. Parties must balance spending on campaign advertising, staff salaries, research, and grassroots mobilization. Transparency in financial management is equally vital, particularly in jurisdictions with strict campaign finance regulations. Many countries require parties to disclose their sources of income and expenditures publicly, ensuring accountability. Poor financial management, such as overspending or misallocation of funds, can cripple a party’s operations and damage its reputation.

A comparative analysis of funding mechanisms across different political systems highlights both challenges and opportunities. In countries with robust public funding, parties may enjoy greater financial stability but face constraints on spending. Conversely, in systems heavily reliant on private donations, parties may have more flexibility but risk becoming beholden to wealthy donors. For example, Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) combines public funding with membership fees, while the U.S. Democratic and Republican parties depend heavily on private contributions. Each model has its trade-offs, and parties must adapt their strategies to align with their national contexts.

To optimize funding mechanisms, parties should adopt a multi-pronged approach. First, diversifying revenue sources can reduce financial vulnerability. This might include expanding membership bases, launching crowdfunding campaigns, or seeking international funding where permissible. Second, cultivating long-term donor relationships based on shared values can provide sustained support. Third, investing in financial management tools and expertise ensures efficient resource allocation. Finally, embracing transparency builds public trust and mitigates risks associated with scandal. By mastering these elements, political parties can secure the financial foundation needed to achieve their goals while maintaining integrity and independence.

Understanding Hillary Clinton's Political Party: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Ideological Alignment: Core principles, platforms, and how they guide party actions and policies

Political parties are not mere collections of individuals seeking power; they are structured around core principles that define their identity and guide their actions. These principles, often encapsulated in a party’s platform, serve as the ideological compass that shapes policies, strategies, and public stances. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States emphasizes social justice, equality, and government intervention to address economic disparities, while the Republican Party prioritizes limited government, free markets, and individual liberty. These core principles are not static; they evolve in response to societal changes, yet they remain the bedrock of a party’s identity.

Consider the role of platforms in translating ideological alignment into actionable policies. A party’s platform is a detailed statement of its beliefs and policy proposals, designed to attract voters and guide elected officials. For example, the Green Party’s platform globally advocates for environmental sustainability, often proposing specific measures like carbon taxes or renewable energy subsidies. Such platforms are not just campaign tools; they are binding documents that hold parties accountable to their ideological commitments. When a party deviates from its platform, it risks alienating its base, as seen in cases where centrist factions within left-leaning parties push for policies that dilute progressive ideals.

The interplay between core principles and practical politics often tests a party’s ideological alignment. Parties must balance their ideals with the realities of governance, which can lead to internal tensions. For instance, a conservative party advocating for fiscal restraint may face pressure to increase spending during economic crises. Here, the party’s leadership must decide whether to adhere strictly to its principles or adapt to immediate needs. This decision-making process reveals the flexibility—or rigidity—of a party’s ideological framework and can determine its long-term viability.

To maintain ideological coherence, parties employ mechanisms like caucuses, think tanks, and policy committees. These bodies ensure that policies align with core principles by vetting proposals and educating members. For example, the Conservative Party in the UK relies on its Policy Forum to engage grassroots members in shaping its agenda, ensuring that policies reflect both ideological purity and public sentiment. Such structures are critical for parties to remain relevant in a rapidly changing political landscape.

Ultimately, ideological alignment is the lifeblood of political parties, distinguishing them from one another and providing voters with clear choices. Without a strong ideological foundation, parties risk becoming amorphous entities driven by opportunism rather than conviction. Voters, in turn, must scrutinize how well a party’s actions align with its stated principles. By doing so, they can hold parties accountable and ensure that democracy functions as a contest of ideas, not just personalities.

Understanding the CDU's Political Ideology and Policy Direction in Germany

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The basic structure of a political party typically includes a hierarchy with local, regional, and national levels. At the local level, there are grassroots organizations or precincts. Above them are county or district committees, followed by state or provincial committees. At the national level, there is a central governing body, often led by a chairperson or executive committee.

Party leaders, such as the chairperson, secretary, or spokesperson, play crucial roles in shaping the party’s direction, strategy, and public image. They oversee fundraising, campaign management, policy development, and coordination between different levels of the party organization. Leaders also act as the primary representatives of the party in public and media interactions.

Decisions within a political party are typically made through a combination of democratic processes and leadership directives. Local and regional committees may hold meetings or conventions to discuss and vote on issues, while the national leadership often has final authority on major decisions. Some parties also involve members in decision-making through primaries, caucuses, or internal elections.

Party members form the base of the organization and are involved in various activities such as campaigning, fundraising, and community outreach. They often participate in local meetings, vote in internal elections, and help shape party policies through feedback and discussions. Active members may also run for party positions or represent the party in public offices.