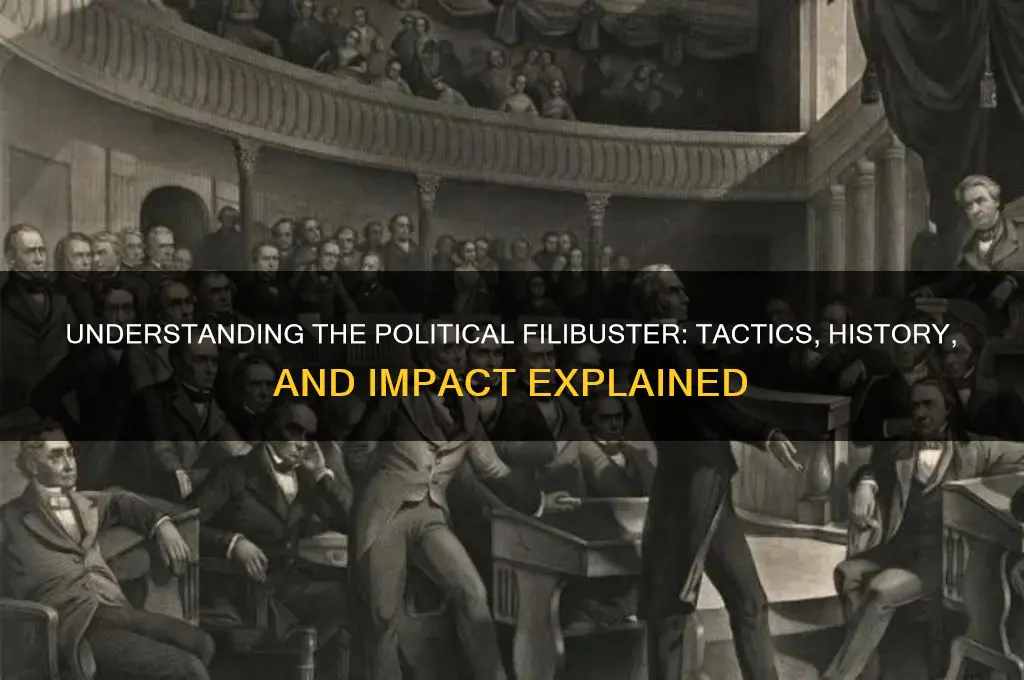

The political filibuster is a procedural tactic used in legislative bodies, most notably in the United States Senate, to delay or block a vote on a bill or nomination by extending debate indefinitely. Unlike traditional filibusters, which often involve lengthy speeches, modern filibusters are typically executed through procedural motions, requiring a supermajority (usually 60 out of 100 senators) to invoke cloture and end debate. This mechanism has become a central tool in partisan strategy, allowing the minority party to obstruct legislation or appointments they oppose, often leading to gridlock and intensifying political polarization. While proponents argue it protects minority rights and encourages bipartisan compromise, critics contend it undermines democratic efficiency and enables obstructionism. The filibuster’s role in shaping legislative outcomes and its implications for governance remain a contentious issue in American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A procedural tactic used in legislative bodies to delay or block a vote on a bill by extending debate indefinitely. |

| Origin | Rooted in the U.S. Senate's tradition of unlimited debate, though not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution. |

| Purpose | To prevent a bill from being voted on, often due to lack of a supermajority (typically 60 votes in the U.S. Senate). |

| Mechanism | Senators continue speaking on the floor, effectively preventing a vote unless a cloture motion (requiring 60 votes) is passed to end debate. |

| Historical Use | Historically used sparingly, but has become more common in recent decades, particularly for partisan purposes. |

| Impact | Can stall or kill legislation, even if it has majority support, by exploiting procedural rules. |

| Criticism | Accused of undermining majority rule and enabling minority obstruction, especially in polarized political climates. |

| Reforms | Proposals include reducing the cloture threshold or eliminating the filibuster altogether, though such changes require significant political will. |

| Notable Examples | Used to block civil rights legislation in the mid-20th century and more recently on issues like healthcare and voting rights. |

| Current Status | Remains a key feature of the U.S. Senate, though its use and potential reforms are subjects of ongoing debate. |

Explore related products

$27.58 $47

What You'll Learn

- Origins and History: Brief overview of the filibuster's historical development in U.S. political procedures

- Rules and Procedures: Explanation of Senate rules enabling filibusters and cloture mechanisms

- Notable Filibusters: Highlighting significant filibuster instances and their political impacts

- Criticism and Reform: Discussing debates over filibuster effectiveness and calls for reform

- Impact on Legislation: Analyzing how filibusters influence policy-making and legislative outcomes

Origins and History: Brief overview of the filibuster's historical development in U.S. political procedures

The political filibuster, a procedural tactic allowing a minority to delay or block legislative action through extended debate, has deep roots in U.S. political history. Its origins can be traced back to the early days of the U.S. Senate, which initially operated under rules that permitted unlimited debate. This tradition of open-ended discussion was inherited from the British Parliament, where similar practices existed. However, the filibuster as a deliberate obstructionist tool began to take shape in the 19th century. The term "filibuster" itself, derived from the Dutch word "vrijbuiter" (pirate or plunderer), was first applied to senators who hijacked legislative proceedings with lengthy speeches to prevent votes on bills they opposed.

The first notable filibuster occurred in 1837 when a group of Whig senators attempted to block a motion to expel Senator John C. Calhoun from their party. By the mid-19th century, filibusters became more common, particularly during debates over slavery and states' rights. The lack of a formal rule to end debate allowed senators to speak indefinitely, effectively killing legislation. This tactic was frequently used by Southern senators to block civil rights and anti-slavery measures, highlighting its early role as a tool for preserving the status quo and minority interests.

The filibuster's modern framework emerged in 1917 when the Senate adopted Rule 22, also known as the cloture rule, which allowed a two-thirds majority to end debate. This was intended to curb excessive filibusters while preserving the Senate's tradition of extended deliberation. Over time, the threshold for invoking cloture was lowered to three-fifths (60 votes) in 1975, making it slightly easier to overcome filibusters but still requiring a supermajority. This change reflected the growing tension between the filibuster's role in protecting minority rights and its potential to paralyze legislative action.

Throughout the 20th century, the filibuster became a central feature of Senate procedure, often used to block significant legislation. Notably, it was employed by Southern senators to obstruct civil rights bills, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which required extensive effort and a bipartisan coalition to overcome. Despite its controversial history, the filibuster has endured as a symbol of the Senate's commitment to deliberation and consensus-building, even as debates continue over its impact on governance and democracy.

In recent decades, the filibuster has evolved further, with its use expanding beyond major legislation to routine matters, leading to increased polarization and gridlock. Efforts to reform or eliminate the filibuster have gained traction, particularly among those who view it as an outdated mechanism that undermines majority rule. However, its historical development underscores its enduring significance in U.S. political procedures, reflecting the Senate's unique role as a deliberative body and the ongoing struggle to balance majority power with minority rights.

Unlocking Power Dynamics: Why Study Politics at University?

You may want to see also

Rules and Procedures: Explanation of Senate rules enabling filibusters and cloture mechanisms

The political filibuster is a procedural tactic in the United States Senate that allows a minority of senators to delay or block a vote on legislation by extending debate indefinitely. This practice is deeply rooted in the Senate's rules and procedures, which prioritize deliberation and consensus-building over swift decision-making. Central to the filibuster is the Senate's tradition of unlimited debate, enshrined in Rule XIX, which permits senators to speak for as long as they wish unless a cloture motion is invoked to end debate. This rule, combined with the absence of a formal mechanism to automatically move to a vote, creates the conditions necessary for a filibuster to occur.

The filibuster is not explicitly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution but has evolved as a result of the Senate's standing rules and precedents. Historically, senators could hold the floor for hours or even days, reading speeches, books, or other materials to prevent a vote. While this tactic can be used to highlight opposition to a bill, it often serves as a tool to force negotiations or amendments. The filibuster effectively requires a supermajority of 60 votes to advance most legislation, as this is the threshold needed to invoke cloture and end debate under Rule XXII.

Rule XXII, also known as the cloture rule, is the primary mechanism for overcoming a filibuster. To invoke cloture, 16 senators must sign a cloture petition, which is then presented on the Senate floor. After a waiting period, the Senate votes on the cloture motion. If three-fifths of the Senate (60 votes out of 100) support the motion, debate is limited to an additional 30 hours, after which a final vote on the legislation must occur. This process ensures that the minority has a voice but does not allow them to obstruct indefinitely.

Exceptions to the 60-vote threshold exist for certain types of legislation. For example, budget reconciliation bills, which pertain to spending and revenue, are subject to a simple majority vote and are not filibusterable. Similarly, nominations for executive branch positions and most judicial appointments (except for Supreme Court nominees) are now subject to a simple majority vote following changes to Senate rules in recent years. These exceptions highlight the Senate's flexibility in adapting its procedures to balance majority rule with minority rights.

Critics of the filibuster argue that it undermines democracy by allowing a minority to block popular legislation, while supporters contend that it fosters bipartisanship and protects against hasty decision-making. Regardless of perspective, the filibuster remains a defining feature of the Senate's procedural landscape, shaped by its rules and traditions. Understanding these rules—particularly Rule XIX and Rule XXII—is essential to grasping how the filibuster functions and how it can be navigated or overcome in the legislative process.

Education and Politics: Unraveling the Inextricable Link in Society

You may want to see also

Notable Filibusters: Highlighting significant filibuster instances and their political impacts

The political filibuster is a procedural tactic used in legislative bodies, particularly in the United States Senate, to delay or block a vote on a bill by extending debate indefinitely. Unlike traditional debate, a filibuster often involves lengthy speeches, procedural motions, or other tactics to consume time and prevent a vote. To end a filibuster, a cloture motion typically requires a supermajority vote (60 out of 100 senators in the U.S. Senate). Filibusters have been used throughout history to shape political outcomes, often highlighting deep ideological divides or minority resistance to majority rule. Below are notable filibuster instances and their significant political impacts.

One of the most famous filibusters occurred in 1964 when Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina led a 24-hour and 18-minute filibuster against the Civil Rights Act. Thurmond, a staunch segregationist, sought to prevent the passage of legislation that would outlaw discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Despite his efforts, the filibuster ultimately failed, and the Civil Rights Act was passed. This filibuster underscored the deep racial divisions in the United States and highlighted the lengths to which some lawmakers would go to preserve the status quo. The political impact was profound, as the Act became a cornerstone of the civil rights movement, reshaping American society and politics.

Another significant filibuster took place in 2010 when Senator Jim Bunning of Kentucky blocked a bill to extend unemployment benefits and other federal programs, demanding that the bill be financed without adding to the deficit. Bunning's filibuster lasted several days and drew widespread criticism, as it delayed critical aid to millions of Americans during the Great Recession. Although the filibuster was eventually overcome, it exposed the challenges of governing in a polarized political environment. The incident also reignited debates about filibuster reform, with critics arguing that the tactic was being abused to obstruct essential legislation.

In 2013, Senator Wendy Davis of Texas conducted an 11-hour filibuster to block a bill that would impose strict regulations on abortion clinics, effectively limiting access to abortion services in the state. Davis's filibuster gained national attention and became a symbol of resistance against efforts to restrict reproductive rights. Although the bill initially passed due to procedural maneuvers, the filibuster galvanized opposition and led to further legal challenges. The political impact was significant, as it mobilized women's rights advocates and sparked a broader conversation about reproductive freedom in the United States.

A more recent example is the 2021 filibuster of the For the People Act, a sweeping voting rights and campaign finance reform bill. Republican senators used the filibuster to block the legislation, arguing that it infringed on states' rights to regulate elections. This filibuster highlighted the ongoing battle over voting rights in the U.S., particularly in the wake of the 2020 election and efforts by some states to enact restrictive voting laws. The failure to pass the bill underscored the limitations of the filibuster in advancing major legislative priorities and fueled calls for filibuster reform or elimination.

These notable filibusters demonstrate the tactic's power to shape political outcomes, often reflecting broader societal and ideological conflicts. While filibusters can serve as a check on majority power and protect minority rights, they have also been criticized for enabling obstruction and gridlock. The political impacts of these instances extend beyond the immediate legislation, influencing public discourse, mobilizing advocacy efforts, and prompting debates about the role of the filibuster in modern governance. As the filibuster continues to evolve, its use in notable instances remains a critical aspect of understanding its role in the political landscape.

How Political Parties Choose Electors in the U.S. Electoral System

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Criticism and Reform: Discussing debates over filibuster effectiveness and calls for reform

The political filibuster, a tactic allowing a minority to delay or block legislation by extending debate indefinitely, has long been a subject of criticism and calls for reform. Critics argue that it undermines democratic principles by allowing a small group to thwart the will of the majority, particularly in the U.S. Senate, where a supermajority (60 votes) is often required to end debate. This mechanism, originally intended to encourage deliberation and protect minority rights, has increasingly been used as a tool of obstruction, paralyzing legislative progress on critical issues such as healthcare, climate change, and voting rights. The filibuster’s effectiveness in fostering bipartisanship is questioned, as it often incentivizes gridlock rather than compromise.

One major criticism is that the filibuster disproportionately empowers the minority party, creating a system where even widely supported bills can be stalled or killed. This dynamic is seen as antithetical to the concept of majority rule, a cornerstone of democratic governance. Proponents of reform argue that the filibuster has been weaponized in modern politics, with both parties using it to gain leverage rather than to engage in meaningful debate. For instance, the number of filibusters and threats of filibusters has skyrocketed in recent decades, reflecting a shift from its occasional use to a routine legislative hurdle. This has led to accusations that the filibuster is no longer a tool for principled opposition but a mechanism for partisan obstruction.

Calls for reform have taken various forms, ranging from outright abolition to modifications that would limit its use. One proposal is the return to the "talking filibuster," which would require senators to actively hold the floor and debate, rather than merely threatening to filibuster. This change would increase the cost of obstruction, as senators would need to invest significant time and effort, potentially reducing its overuse. Another reform idea is to lower the threshold for cloture (the motion to end debate) from 60 votes to a simple majority, aligning the Senate more closely with democratic norms. Advocates argue that such reforms would restore balance while still allowing for minority input.

Opponents of reform, however, contend that the filibuster serves as a crucial check on power, preventing hasty or partisan legislation. They argue that its elimination could lead to a "tyranny of the majority," where temporary majorities could enact sweeping changes without adequate deliberation or minority protections. This perspective emphasizes the filibuster’s role in fostering stability and encouraging bipartisan cooperation. Critics of reform also warn that altering or abolishing the filibuster could have unintended consequences, such as escalating partisan warfare and eroding institutional norms.

The debate over filibuster reform is deeply intertwined with broader discussions about the role of the Senate in American democracy. The Senate’s unique structure, with equal representation for each state regardless of population, already gives smaller states disproportionate power. Reforming or eliminating the filibuster could further shift the balance of power, raising questions about federalism and representation. Additionally, historical context plays a role, as the filibuster has been used both to block progressive legislation and to obstruct civil rights reforms, complicating its legacy and fueling arguments on both sides of the reform debate.

Ultimately, the filibuster’s effectiveness and necessity remain contentious issues, reflecting deeper divides over the functioning of democratic institutions. As polarization intensifies and legislative gridlock persists, pressure for reform is likely to grow. However, any changes to the filibuster would require careful consideration of their long-term implications, ensuring that efforts to enhance democracy do not inadvertently undermine it. The ongoing debate underscores the need for a nuanced approach that balances majority rule with minority rights, fostering a more functional and equitable legislative process.

Walgreens' Political Affiliations: Uncovering Corporate Support and Donations

You may want to see also

Impact on Legislation: Analyzing how filibusters influence policy-making and legislative outcomes

The political filibuster, a tactic primarily associated with the U.S. Senate, allows a minority of senators to delay or block a vote on a bill by extending debate indefinitely. This procedural maneuver requires a supermajority of 60 votes to overcome through a process called cloture. The filibuster’s impact on legislation is profound, as it fundamentally alters the dynamics of policy-making by empowering the minority party. In practice, this means that even if a bill has majority support (51 votes), it can still be stalled or defeated if it fails to secure the necessary 60 votes to end debate. This mechanism forces bipartisan negotiation, as the majority party must either compromise with the minority or abandon the legislation altogether. While this can foster collaboration, it also creates a high barrier for passing contentious or transformative policies, often resulting in legislative gridlock.

One of the most significant impacts of the filibuster is its tendency to favor the status quo. Since overcoming a filibuster requires a supermajority, incremental or moderate legislation is more likely to pass, while bold or controversial proposals often fail. This dynamic can stifle progressive or conservative reforms, depending on the political context, as both parties may use the filibuster to block the other’s agenda. For example, major initiatives such as healthcare reform, climate change legislation, or voting rights bills have faced significant hurdles due to filibuster threats. As a result, policy-making becomes more reactive than proactive, addressing only the least divisive issues rather than tackling systemic challenges that require comprehensive solutions.

The filibuster also influences legislative strategy and prioritization. Knowing that certain bills are likely to face a filibuster, party leaders may choose to focus on less ambitious or more bipartisan measures, even if they fall short of addressing the root causes of pressing issues. This can lead to a mismatch between public demand for action and the legislative output, as lawmakers prioritize political feasibility over policy effectiveness. Additionally, the filibuster encourages the use of budgetary reconciliation, a process that allows certain bills to pass with a simple majority, but only if they directly impact federal spending or revenue. While this provides a workaround for some legislation, it limits the scope of what can be achieved and often results in narrower, less impactful policies.

Another critical impact of the filibuster is its effect on executive power. Faced with legislative gridlock, presidents may resort to executive orders, regulatory actions, or other unilateral measures to advance their agendas. While this can provide temporary solutions, it also undermines the principle of checks and balances and can lead to policy instability, as executive actions are more easily reversed by future administrations. This shift in power dynamics further diminishes the role of Congress as the primary lawmaking body, eroding its effectiveness and legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

Finally, the filibuster has broader implications for democratic representation and accountability. By allowing a minority to block majority-supported legislation, it raises questions about whether the Senate is truly reflecting the will of the people. This is particularly problematic in a body where each state, regardless of population size, has equal representation. Critics argue that the filibuster exacerbates this imbalance, giving disproportionate power to smaller, often more conservative states. Proponents, however, contend that it protects minority rights and encourages consensus-building. Regardless of perspective, the filibuster’s impact on legislation is undeniable, shaping not only the content of laws but also the very nature of American governance.

Trump's Political Stance: Unraveling His Conservative Populist Agenda Today

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The political filibuster is a procedural tactic used in legislative bodies, particularly in the United States Senate, to delay or block a vote on a bill or nomination by extending debate indefinitely.

A filibuster works by allowing senators to speak for as long as they wish, effectively preventing a vote unless a supermajority (typically 60 out of 100 senators) agrees to end debate through a process called cloture.

Yes, a filibuster can be stopped if 60 senators vote for cloture, which ends debate and allows the bill or nomination to proceed to a final vote.

While traditional debate is a structured discussion with time limits, a filibuster is an extended, often unlimited debate intended to delay or prevent a vote, sometimes involving irrelevant or repetitive speeches.

Yes, certain legislative actions, such as budget reconciliation and nominations, are subject to a simple majority vote and are not filibuster-proof, reducing the need for a supermajority.