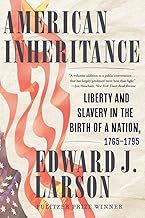

The issue of slavery in the US Constitution is a highly controversial topic in American history and government. The Constitution, created by We the People, sought to ensure justice and protect liberty, but its protection and institutionalization of slavery, as well as its exclusion of non-white men, are considered its biggest flaws. The framers of the Constitution, some of whom were slave owners, consciously avoided using the word slave, but included provisions that protected slavery, such as the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required runaway slaves to be returned to their owners, and the Three-Fifths Clause, which gave the South extra representation in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. The question of whether the Constitution was a pro-slavery document is still debated, as it also created a central government with the power to eventually abolish slavery, which it did with the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, ending slavery in the US forever.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The 13th Amendment

The road to the 13th Amendment was not without its challenges. Despite the growing abolitionist sentiment, the Southern states seceded from the Union after the election of Abraham Lincoln as president in 1860, as he opposed the expansion of slavery into Western territories. This secession led to the American Civil War. During the war, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, which came into effect on January 1, 1863, proclaiming the freedom of slaves in ten states still in rebellion. However, this proclamation did not apply to the border states that had remained loyal to the Union, nor did it end slavery nationwide.

In the final years of the Civil War, lawmakers debated proposals for Reconstruction, including calls for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery permanently. On December 14, 1863, Representative James Mitchell Ashley of Ohio introduced a bill proposing such an amendment. Lincoln recognised that the Emancipation Proclamation alone would not be enough to guarantee the abolishment of slavery, and he played an active role in ensuring the passage of the 13th Amendment through Congress. Although the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. Lincoln's insistence that the passage of the amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the 1864 presidential election paid off, and the House passed the bill in January 1865.

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States finally addressed the issue of slavery, which had been a source of controversy and tension since the nation's founding.

The Constitution's Peaceful Power Transfer: A Historical Legacy

You may want to see also

Fugitive slave clause

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. The clause requires that a "Person held to Service or Labour" (usually a slave, apprentice, or indentured servant) who escapes to another state must be returned to their master in the state from which they escaped. The exact wording of the clause is as follows:

> No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

The Fugitive Slave Clause was adopted at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Notably, the clause does not use the words "slave" or "slavery", and historian Donald Fehrenbacher argues that the intent of the clause was to make it clear that slavery existed only under state law, not federal law. A last-minute change to the clause's wording replaced the phrase "legally held to service or labour in one state" with "held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof". This revision made it impossible to interpret the Constitution as legally sanctioning slavery.

The Fugitive Slave Clause was enforced by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, with the enforcement provisions strengthened as part of the Compromise of 1850. Under the Supreme Court's interpretation of the clause, the owner of an enslaved person had the same right to seize and repossess them in another state as the local laws of their own state granted to them. State laws that penalised such a seizure were deemed unconstitutional. The Fugitive Slave Clause also enabled the kidnapping of free African Americans, who were then illegally enslaved. The case of Solomon Northup, a free man abducted in Washington, D.C. and enslaved in Louisiana for twelve years, highlighted the systemic abuse enabled by the clause.

Resistance to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Clause increased in the North during the 19th century, particularly after the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Several Northern states enacted "personal liberty laws" to protect their Black residents from kidnapping and provide procedural safeguards for accused fugitives. For example, Massachusetts prohibited state officials from assisting in fugitive slave renditions and banned the use of state facilities for holding alleged fugitives. In 1859, the Supreme Court ruled in Ableman v. Booth that states could not obstruct federal enforcement, reinforcing federal supremacy but further polarising public opinion.

The Fugitive Slave Clause was effectively nullified by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery except as a punishment for criminal acts.

Constitutional Health: Asking Patients the Right Questions

You may want to see also

Abolitionist movement

The abolitionist movement was an organised effort to end the practice of slavery in the United States. It took place from about 1830 to 1870, with the goal of eradicating slave ownership and liberating enslaved individuals. The movement was inspired by the religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening, which emphasised the idea that all men are created equal in the eyes of God. It officially emerged in states like New York and Massachusetts, with women and men of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society taking the lead.

Many Americans, including free and formerly enslaved people, actively supported the abolitionist movement. Some of the most prominent leaders of the movement were Black men and women who had escaped slavery, such as Frederick Douglass, who published a memoir about his experiences and was an instrumental figure in the abolitionist movement. Other notable abolitionists include William Lloyd Garrison, who started the publication 'The Liberator', and Harriet Beecher Stowe, an author best known for her novel 'Uncle Tom's Cabin'.

Abolitionists employed various tactics, including sending petitions to Congress, running for political office, and distributing anti-slavery literature in the South. The movement divided the country, with supporters and critics engaging in heated debates and even violent confrontations. The divisiveness fuelled by the abolitionist movement, along with other factors, ultimately led to the Civil War and the end of slavery in America.

The issue of slavery was a contentious topic during the drafting of the United States Constitution. While the word "slavery" was not explicitly mentioned in the original text, the Constitution dealt with American slavery in several provisions and indirectly protected the institution. For example, the Three-Fifths Clause gave Southern states more representation in the House and the Electoral College by counting three-fifths of each state's slave population towards its total population. Additionally, the Constitution prohibited Congress from banning the importation of slaves until 1808 and required states to return fugitive slaves to their owners. These measures ensured that slavery remained a national issue embedded in American governance.

Legislative Powers: Constitutional Limits Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.36 $19.95

The Civil War

The issue of slavery was a central cause of the American Civil War. The Constitution of 1789 contained several provisions related to slavery, though it did not use the word "slave". One of these provisions, Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1, prohibited the federal government from limiting the importation of "persons" where state governments allowed it, for 20 years after the Constitution took effect. This clause was a compromise between Northern and Southern states, reflecting their differing economic interests and views on slavery. The Southern states, where slavery was pivotal to the economy, wanted to protect the practice, while some Northern states had already taken steps towards abolition.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the immorality of slavery and the need for its abolition became increasingly apparent. Influential figures such as Theodore Parker, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Frederick Douglass repeatedly invoked the Puritan heritage of the country to argue for abolition. Thomas Jefferson, in his "Notes on the State of Virginia" (1785), denounced the slave trade as "a cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty". James Madison, in his "Notes on the Federal Convention" (1787), echoed these sentiments, stating that the slave trade continued "in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity".

Despite these critiques, some politicians and statesmen before the Civil War held positive views of slavery. Senator John Calhoun, for example, argued in 1848 that the natural rights language in the Declaration of Independence was "dangerous" and "erroneous". He asserted that slavery was not a violation of natural law but rather a "positive good" for both the slave and society. This view was shared by several important 19th-century politicians, who contradicted the Founders' belief that slavery was morally wrong.

The tensions over slavery came to a head in the mid-19th century. In 1850, the newly rich, cotton-growing South threatened to secede from the Union. Bloody fighting broke out over slavery in the Kansas Territory. When Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election on a platform of halting the expansion of slavery, several slave states seceded to form the Confederacy. The Civil War began when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina.

During the war, several jurisdictions abolished slavery, and Union measures such as the Confiscation Acts and the Emancipation Proclamation effectively ended slavery in most places. The Thirteenth Amendment, passed at the end of the war and ratified in 1865, officially abolished slavery in the United States. This amendment, along with the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans and addressed the racial inequality that had been entrenched by slavery.

Why Ratify? Benefits of the Constitution

You may want to see also

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation

On January 1, 1863, as the American Civil War entered its third year, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation declared that all persons held as slaves within the rebellious states were now free. Lincoln's order stated:

> [A]ll persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a significant moment in the road to slavery's final destruction in the United States. It changed the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. Importantly, it also allowed for former slaves to join the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union.

Despite its sweeping wording, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in scope. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery in place in the border states that had not joined the Confederacy. Certain parts of the Confederacy that had come under Northern control were also expressly exempted. Moreover, the freedom promised by the proclamation depended upon a Union military victory. The proclamation was never challenged in court, and Lincoln also worked to ensure the abolition of slavery in the Southern states through Reconstruction plans.

The original document, officially Proclamation 95, is preserved in the National Archives in Washington, DC.

Founding Fathers' Most Powerful Pro-Constitution Propaganda Tactic

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US Constitution protected the institution of slavery. Article 1, Section 9, prohibited Congress from banning the importation of slaves until 1808, and Article 5 prohibited this from being amended. The Constitution also prohibited Congress from outlawing the Atlantic slave trade for twenty years.

The Fugitive Slave Clause, located in Article IV, Section 2, required that an escaped slave be returned to their owner. The Three-Fifths Compromise, mentioned in Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, stated that enslaved people would be regarded as "three-fifths" of a free citizen.

The 13th Amendment to the US Constitution, passed in 1865, abolished slavery by stating that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime...shall exist within the United States". This was preceded by Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which freed slaves in Confederate states in rebellion.

![The Constitution's Introductory Phrase: A Powerful [Phrase]](/images/resources/what-is-the-introductory-phrase-of-the-constitution-known-as_20250706235718.webp)