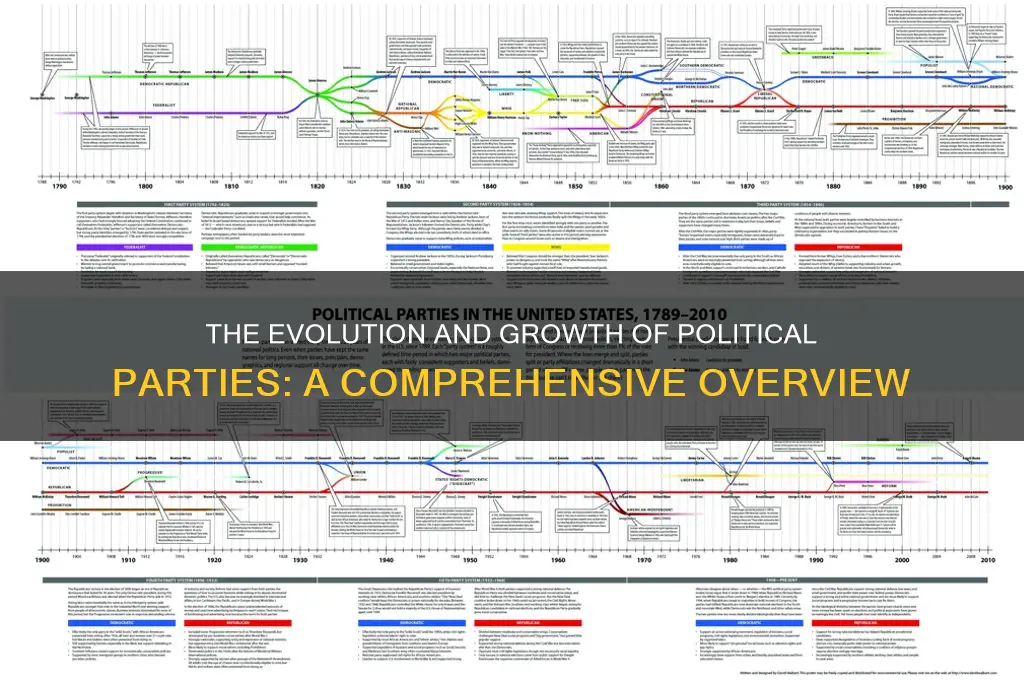

The development of political parties is a fundamental aspect of modern democratic systems, tracing its origins to the need for organized representation of diverse interests and ideologies within a society. Emerging as a response to the complexities of governance, political parties evolved from informal factions and coalitions into structured institutions that mobilize support, articulate policies, and compete for power. Historically, their growth has been shaped by socio-economic changes, technological advancements, and shifts in political consciousness, with early examples seen in 18th-century Europe and the United States. Over time, parties have adapted to changing societal demands, adopting distinct platforms, organizational hierarchies, and strategies to engage citizens. Their development reflects broader trends in democratization, reflecting both the strengths and challenges of pluralistic political systems. Understanding this evolution is crucial for grasping how political parties influence governance, shape public discourse, and mediate between the state and its citizens.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origins | Political parties typically emerge from social movements, ideological groups, or factions within existing power structures. They often develop in response to societal changes, economic shifts, or perceived failures of existing governance. |

| Ideological Formation | Parties are formed around core ideologies or policy platforms, such as conservatism, liberalism, socialism, or environmentalism. These ideologies shape their goals, strategies, and appeal to voters. |

| Organizational Structure | Parties develop hierarchical structures with leaders, committees, and local chapters. They establish rules for membership, candidate selection, and decision-making processes. |

| Mobilization and Recruitment | Parties recruit members and supporters through campaigns, grassroots organizing, and outreach efforts. They mobilize voters through rallies, media, and community engagement. |

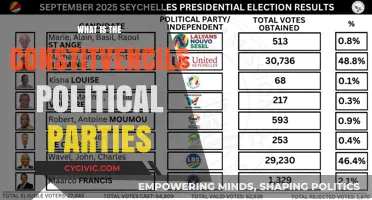

| Electoral Participation | Parties compete in elections to gain political power. They field candidates, develop campaign strategies, and seek to win seats in legislative bodies or executive positions. |

| Policy Influence | Once in power, parties implement their policy agendas, shape legislation, and influence governance. They negotiate with other parties and interest groups to achieve their objectives. |

| Adaptation and Evolution | Parties evolve over time in response to changing societal values, demographic shifts, and political landscapes. They may rebrand, shift ideologies, or merge with other parties. |

| Funding and Resources | Parties rely on funding from donations, membership fees, and public financing. They invest in resources like campaign staff, technology, and media to enhance their effectiveness. |

| Media and Communication | Parties use media, social platforms, and public relations to communicate their message, shape public opinion, and counter opponents' narratives. |

| International Affiliations | Many parties affiliate with international organizations or ideological alliances (e.g., Socialist International, Liberal International) to share strategies and resources. |

| Challenges and Decline | Parties may face challenges such as internal divisions, corruption scandals, or declining voter trust, leading to loss of support or dissolution. |

| Role in Democracy | Political parties are essential for democratic systems, as they aggregate interests, facilitate representation, and provide mechanisms for accountability and governance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of political parties

The concept of political parties as we know them today is a relatively modern phenomenon, with roots tracing back to the 17th and 18th centuries. The earliest semblance of organized political factions emerged in England during the Exclusion Crisis (1679–1681), when Whigs and Tories coalesced around the issue of whether to exclude the Catholic James, Duke of York, from the throne. These groups were less formal parties and more loose alliances of elites, but they laid the groundwork for structured political organization. The Whigs advocated for parliamentary power and religious tolerance, while the Tories supported monarchical authority and the established Church of England. This division marked the beginning of partisan politics, where competing interests sought to influence governance systematically.

Across the Atlantic, the American Revolution and the subsequent formation of the United States provided fertile ground for the development of political parties. Initially, the Founding Fathers, such as George Washington, opposed the idea of parties, fearing they would lead to division and corruption. However, by the 1790s, the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, emerged as the first true political parties in the U.S. The Federalists championed a strong central government and industrialization, while the Democratic-Republicans advocated for states’ rights and agrarian interests. This period demonstrated how parties could crystallize around ideological and economic differences, becoming essential tools for mobilizing public opinion and structuring political competition.

In Europe, the 19th century saw the rise of political parties as vehicles for mass participation in politics, particularly with the expansion of suffrage. The Industrial Revolution and the rise of the working class fueled the growth of socialist and labor parties, such as the British Labour Party and the German Social Democratic Party. These parties organized around demands for workers’ rights, social welfare, and democratic reforms, challenging the dominance of conservative and liberal elites. Meanwhile, in France, the aftermath of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era led to the formation of parties based on republicanism, monarchism, and socialism, reflecting the nation’s deep political divisions. This era highlighted how parties could serve as instruments for social change and representation in an increasingly complex society.

A comparative analysis of these historical origins reveals a common thread: political parties emerged in response to societal transformations and the need to manage competing interests. Whether in England’s constitutional struggles, America’s post-revolutionary debates, or Europe’s industrialization, parties provided a framework for organizing political conflict and channeling it into governance. However, their development was not without challenges. Early parties often lacked formal structures, relied heavily on charismatic leaders, and were prone to factionalism. It was only through trial and error that they evolved into the institutionalized entities we recognize today, with defined platforms, membership systems, and mechanisms for candidate selection.

Understanding these historical origins offers practical insights for modern political systems. For instance, the early reliance on elite networks underscores the importance of broadening party inclusivity to reflect diverse societal interests. The ideological clarity of 19th-century parties reminds us of the need for coherent platforms that resonate with voters. Finally, the challenges faced by nascent parties—such as internal divisions and external opposition—highlight the resilience required to sustain political organizations over time. By studying these origins, we can better appreciate the role of parties in democratic systems and identify strategies for strengthening their effectiveness in the 21st century.

Senator Lyle Larson's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Membership

You may want to see also

Evolution of party structures and roles

Political parties have undergone significant transformations in their structures and roles since their inception, adapting to changing societal needs, technological advancements, and democratic demands. Initially, parties were loose coalitions of elites, often centered around charismatic leaders or shared ideologies. For instance, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties in the United States emerged in the late 18th century as informal factions, lacking the formalized structures of modern parties. These early formations were more about personal networks than systematic organizations, reflecting the limited scope of political participation at the time.

As democracies expanded and suffrage broadened, parties evolved into more structured entities to mobilize and represent diverse constituencies. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of mass-membership parties, exemplified by the British Labour Party and the German Social Democratic Party. These organizations developed hierarchical structures, with local branches feeding into national leadership, and began to adopt formal platforms to appeal to a wider electorate. This shift marked a transition from elite-driven factions to institutions capable of mass political engagement, often supported by membership dues and grassroots activism.

The mid-20th century introduced the era of the "catch-all" party, as described by political scientists like Otto Kirchheimer. Parties like the Christian Democratic Union in Germany and the Republican Party in the United States began to de-emphasize rigid ideologies in favor of broader appeals to attract voters across demographic lines. This transformation involved professionalizing campaign strategies, utilizing polling data, and crafting policies to maximize electoral success. However, this shift also led to criticisms of ideological dilution and a focus on short-term political gains over long-term vision.

In recent decades, technological advancements have further reshaped party structures and roles. The digital age has enabled parties to engage directly with voters through social media, bypassing traditional intermediaries like newspapers and television. For example, the Five Star Movement in Italy built its base through online platforms, challenging conventional party hierarchies. Simultaneously, the rise of populist movements has led to more decentralized and leader-centric parties, where charismatic figures dominate decision-making, often sidelining internal democracy. This trend raises questions about the balance between responsiveness to public sentiment and the stability of party institutions.

Understanding these evolutionary stages highlights the adaptability of political parties as essential mechanisms of democracy. From elite factions to mass organizations, catch-all parties, and digitally-driven movements, their structures and roles reflect broader societal changes. For practitioners and observers alike, recognizing these patterns can inform strategies for effective party management, voter engagement, and democratic resilience. The challenge lies in balancing innovation with the core functions of representation and governance, ensuring parties remain relevant in an ever-changing political landscape.

Karen Bass' Political Affiliation: Uncovering Her Party and Ideology

You may want to see also

Influence of ideologies on party formation

Ideologies serve as the bedrock for political party formation, shaping their core principles, policies, and appeal to voters. Consider the rise of socialist parties in 19th-century Europe, born from the ideological ferment of the Industrial Revolution. These parties, rooted in Marxist thought, advocated for workers' rights and economic equality, attracting a distinct constituency alienated by capitalist exploitation. Similarly, conservative parties often emerge from a desire to preserve traditional social structures and values, as seen in the formation of the British Conservative Party, which has historically championed national sovereignty and free-market principles.

The process of party formation is not merely a reflection of existing ideologies but also a dynamic interplay between ideas and political realities. For instance, the Green Party movement, which began as a response to environmental concerns in the 1970s, has since evolved into a global political force. Its ideology, centered on ecological sustainability and social justice, has adapted to local contexts, leading to the creation of Green parties in diverse countries like Germany, Australia, and Brazil. This adaptability demonstrates how ideologies can be both universal and context-specific, influencing party formation across different cultural and political landscapes.

To understand the influence of ideologies on party formation, examine the role of charismatic leaders who articulate and popularize these ideas. Figures like Mahatma Gandhi in India or Nelson Mandela in South Africa did not just lead political movements; they embodied ideologies—nonviolence and anti-apartheid, respectively—that became the foundation of new political parties. The Indian National Congress and the African National Congress were not merely organizations but vehicles for ideologies that mobilized millions. This highlights how ideologies, when championed by influential leaders, can crystallize into political parties with lasting impact.

A practical takeaway for anyone studying or engaging in party formation is to recognize the dual role of ideology: it must be both aspirational and actionable. Aspirational in that it offers a vision for society, and actionable in that it translates into concrete policies and strategies. For example, libertarian parties worldwide advocate for minimal government intervention and individual freedoms, but their success often hinges on how effectively they address immediate voter concerns, such as taxation or privacy rights. Balancing ideological purity with pragmatic politics is crucial for a party’s viability and growth.

Finally, the influence of ideologies on party formation is not static; it evolves with societal changes. The rise of populist parties in recent years, from the Five Star Movement in Italy to the Law and Justice Party in Poland, reflects a shift in ideological focus toward anti-establishment sentiments and national identity. These parties have capitalized on disillusionment with traditional political elites, demonstrating how ideologies can emerge or re-emerge in response to contemporary challenges. As such, understanding the interplay between ideologies and party formation requires a keen awareness of both historical roots and current trends.

Teamsters Union's Political Allegiance: Which Party Gains Their Support?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of elections in party development

Elections serve as the crucible in which political parties are forged, tested, and refined. They are not merely a mechanism for selecting leaders but a dynamic process that shapes party identity, strategy, and survival. Consider the early stages of party development: nascent parties often emerge around a charismatic leader or a singular issue. Elections force these fledgling entities to articulate a broader platform, build organizational structures, and mobilize supporters. For instance, the U.S. Republican Party, born in the 1850s to oppose slavery, quickly evolved into a multifaceted organization through successive electoral campaigns, which compelled it to address economic and social issues beyond its initial focus.

The electoral process also acts as a feedback loop, compelling parties to adapt to the electorate’s shifting demands. Parties that fail to resonate with voters face marginalization or extinction, while those that successfully interpret and respond to public sentiment grow stronger. Take the case of the Labour Party in the U.K., which shifted from its socialist roots to the centrist "New Labour" under Tony Blair in the 1990s. This strategic realignment was driven by repeated electoral defeats and a recognition of the need to appeal to a broader demographic. Elections, therefore, are not just a means to power but a mirror reflecting a party’s relevance and adaptability.

From a practical standpoint, elections provide parties with critical resources for development. Campaign funding, media exposure, and volunteer engagement are all amplified during election seasons. Parties use these periods to expand their grassroots networks, refine messaging, and test leadership capabilities. For example, in India, regional parties like the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) leveraged local elections to build a national presence, using the visibility and organizational momentum gained from smaller contests to compete in general elections. This iterative process of growth underscores the role of elections as both a challenge and an opportunity for party development.

However, the electoral process is not without risks. Over-reliance on short-term electoral gains can lead to policy incoherence or ideological dilution. Parties may prioritize populist appeals over long-term vision, as seen in some European populist movements that sacrifice programmatic depth for immediate electoral success. To mitigate this, parties must balance electoral pragmatism with ideological consistency, using elections as a tool for growth rather than an end in themselves.

In conclusion, elections are the lifeblood of political party development, driving organizational maturation, strategic adaptation, and resource mobilization. They force parties to confront their strengths and weaknesses, rewarding those that evolve and punishing those that stagnate. By understanding this dynamic, parties can harness the electoral process not just to win power but to build enduring institutions capable of shaping the political landscape.

Can Citizens Legally Dismantle a Political Party? Exploring the Possibilities

You may want to see also

Impact of technology on modern parties

Technology has fundamentally reshaped how political parties operate, communicate, and mobilize support. Social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have become battlegrounds for political messaging, allowing parties to reach millions instantly. For instance, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, both major parties leveraged targeted ads and viral campaigns to sway voter opinions. This shift has democratized political participation, enabling smaller parties and grassroots movements to compete with established ones. However, it also raises concerns about misinformation and echo chambers, as algorithms often prioritize engagement over accuracy.

The analytical lens reveals that technology has altered the very structure of political campaigns. Data analytics now drive decision-making, with parties using voter profiling and predictive modeling to tailor messages and allocate resources efficiently. For example, the UK’s Labour Party employed sophisticated data tools in the 2017 general election to identify key constituencies, resulting in unexpected gains. Yet, this reliance on data poses ethical dilemmas, such as privacy violations and the potential for manipulation. Parties must balance innovation with transparency to maintain public trust.

From an instructive perspective, modern parties must adapt to survive in a tech-driven landscape. Step one: invest in digital infrastructure, including robust websites and secure databases. Step two: train staff and volunteers in digital literacy, ensuring they can navigate platforms and tools effectively. Step three: engage with voters authentically, using technology to listen as much as to broadcast. Caution: avoid over-reliance on automation; personal connections still matter. Conclusion: technology is a tool, not a strategy—its effectiveness depends on how parties wield it.

Comparatively, the impact of technology on political parties differs across regions. In developed nations, high internet penetration allows for sophisticated online campaigns, while in developing countries, parties often rely on mobile messaging apps like WhatsApp to reach voters. For instance, in India, the BJP’s 2019 campaign utilized WhatsApp groups to disseminate messages rapidly, contributing to their landslide victory. This disparity highlights the need for context-specific strategies, as one-size-fits-all approaches rarely succeed in diverse political environments.

Descriptively, the fusion of technology and politics has created a 24/7 campaign cycle. News cycles move faster, and parties must respond to developments in real time. A single tweet can spark a national debate or derail a campaign. Take the 2020 U.S. presidential race, where candidates’ social media activity was scrutinized as closely as their policy positions. This constant connectivity demands agility and resilience from parties, as well as a clear, consistent message that resonates across platforms. The takeaway: in the digital age, political parties are not just organizations—they are media entities.

When Can You Join a Political Party? Age Requirements Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The development of political parties refers to the process by which groups with shared political ideologies, interests, or goals organize themselves into structured entities to participate in the political process, often through elections and governance.

Political parties typically form around a common ideology, set of policies, or the leadership of a charismatic figure. They emerge in response to societal needs, political changes, or the desire to represent specific interests within a population.

Political parties play a crucial role in democracy by aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and providing a platform for political competition. They facilitate governance, represent diverse viewpoints, and ensure accountability through elections.

Political parties have evolved from informal factions to highly organized institutions with formal structures, ideologies, and strategies. Technological advancements, changes in voter behavior, and shifts in political landscapes have also influenced their development.