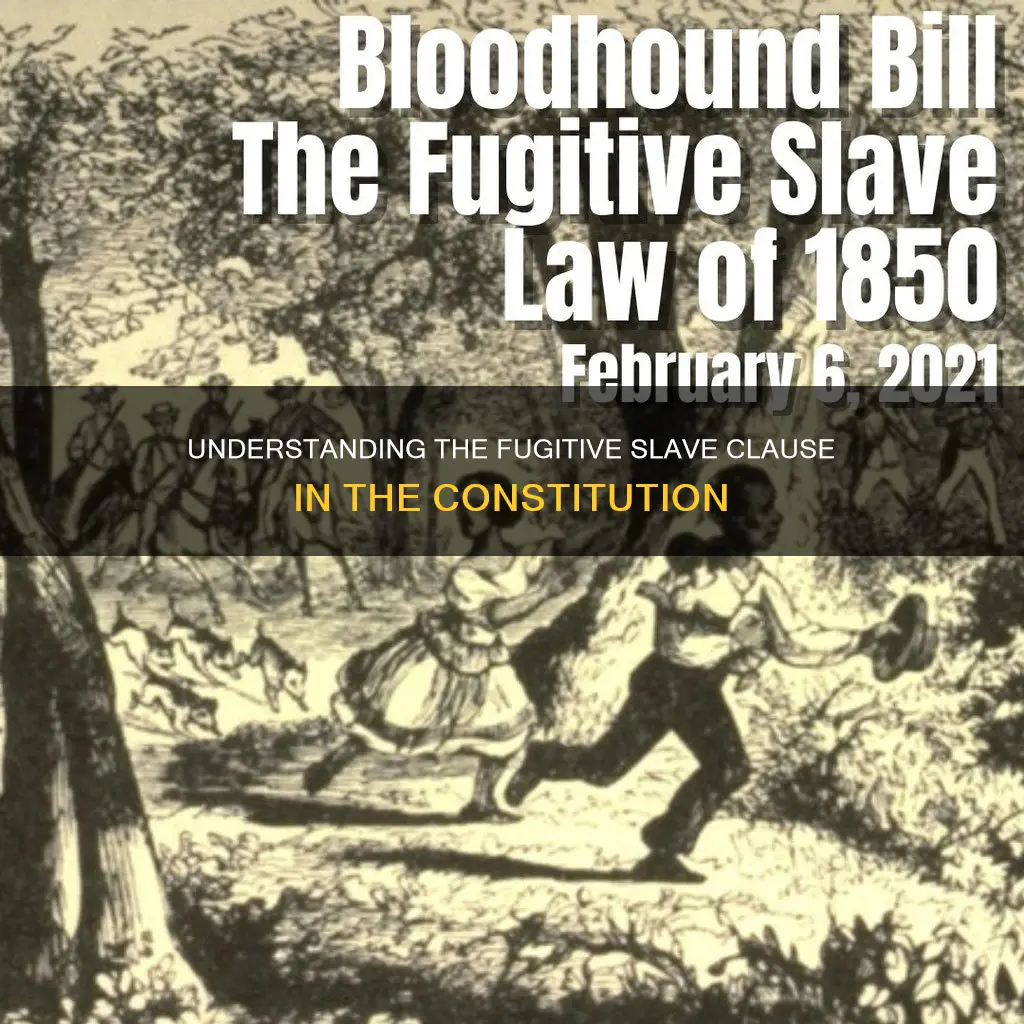

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. It requires that a Person held to Service or Labour who escapes to another state must be returned to their master. The clause was agreed to without dissent at the Constitutional Convention and remained in full effect until the abolition of slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment. The Fugitive Slave Clause formed the basis for the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, which gave slaveholders the right to recover their property from different states.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Article | IV |

| Section | 2 |

| Clause | 3 |

| Purpose | To require a "Person held to Service or Labour" (usually a slave, apprentice, or indentured servant) who flees to another state to be returned to their master in the state from which they escaped. |

| Implementation | Slaveholders had the right to capture enslaved persons who ran away to free states. |

| Enacted | 1793, as part of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. |

| Amendments | Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; 13th Amendment to the US Constitution (abolished slavery except as punishment for criminal acts). |

| Criticism | Northern states argued that it was legalized kidnapping; some passed "personal liberty laws" to protect free Black residents. |

Explore related products

$24.99 $29.99

What You'll Learn

The Fugitive Slave Clause's constitutional legitimacy

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. It requires that a "person held to service or labour" (usually a slave) who flees to another state must be returned to their master in the state from which they escaped. The clause was introduced by Pierce Butler and Charles Pinckney of South Carolina during the Constitutional Convention, and notably does not include the word "slave".

The legitimacy of the Fugitive Slave Clause has been debated by modern legal scholars. Some argue that the vague wording of the clause was a political compromise that avoided overtly validating slavery at the federal level. Historian Donald Fehrenbacher supports this interpretation, believing that the Constitution intended to make it clear that slavery existed only under state law, not federal law. This is reflected in a last-minute change to the clause's wording, from "legally held to service or labour in one state" to "held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof". This revision made it impossible to infer that the Constitution itself legally sanctioned slavery.

Others, however, contend that the clause functionally entrenched slaveholder power. Legal scholar Akhil Reed Amar argues that the Clause’s ambiguity allowed both pro- and anti-slavery factions to claim constitutional ground, reflecting deeper contradictions in the founding document itself. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the Fugitive Slave Clause formed the basis for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which gave slaveholders the right to capture enslaved persons who ran away. The Act was enforced by the federal government, indicating that the Fugitive Slave Clause had conferred a degree of constitutional legitimacy to slavery.

The Fugitive Slave Clause remained in full effect until the abolition of slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment, which rendered it unenforceable and mostly irrelevant. However, it is worth noting that even after the Thirteenth Amendment, people can still be held to service or labour under limited circumstances, as noted by the U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Kozminski.

Understanding a Country's Constitution: Definition and Significance

You may want to see also

Northern resistance to the Fugitive Slave Clause

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. It requires that a "Person held to Service or Labour" who escapes to another state must be returned to their master. The clause does not use the words "slave" or "slavery", but it gave slaveholders the constitutional right to recover their "property" from another state.

Several Northern states responded to the Act by enacting "personal liberty laws" to protect free Black residents and provide safeguards for accused fugitives. For example, Massachusetts prohibited state officials from assisting in fugitive slave renditions and banned the use of state facilities for holding alleged fugitives. Vermont passed the Habeas Corpus Law, which established a state judicial process for people accused of being fugitive slaves, rendering the federal Fugitive Slave Act unenforceable in the state.

Resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act also took the form of direct action, with abolitionists celebrating acts of defiance and resistance to the law. One famous case was the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858, where John Price, an escaped slave, was arrested by a federal marshal and returned to his slaveholder. Authorities in Ohio, sympathetic to Price, arrested the federal marshal and charged him with kidnapping. The National Era reported that only two anti-slavery men were convicted, with the remaining 35 released without charge.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court was the only state high court to declare the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional in 1855, but this was overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1859. Despite this, local Northern juries often acquitted men accused of violating the law, demonstrating continued resistance to its enforcement.

Marbury v. Madison: The Constitutional Clause Explained

You may want to see also

The Fugitive Slave Clause and the 13th Amendment

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. The clause requires a "person held to service or labour" (usually a slave, apprentice, or indentured servant) who flees to another state to be returned to their master in the state from which they escaped. The clause was a compromise between northern and southern states, as slavery was a way of life in the American South but not in the North. It gave slaveholders the constitutional right to recover their "property" from another state.

The Fugitive Slave Clause did not mention the word "slave", but it formed the basis for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which allowed slaveholders to capture enslaved people who had run away. The Act was enforced by the Article IV, Section 2, Clause 2 extradition clause, which regulated interstate extraditions. Under chattel slavery, enslaved people were the property of their enslavers and could be claimed as "escaped slaves".

In the 19th century, Northern resistance to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Clause increased, especially after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This Act required that slaves be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state, and made the federal government responsible for finding, returning, and trying escaped slaves. Several Northern states enacted "personal liberty laws" to protect free Black residents from kidnapping and provide safeguards for accused fugitives. For example, Massachusetts prohibited state officials from assisting in fugitive slave renditions.

The enactment of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery except as punishment for criminal acts, has made the Fugitive Slave Clause mostly irrelevant. The Amendment rendered the clause unenforceable and obsolete, and it is now considered to have been abolished along with the institution of slavery. However, it has been noted that people can still be held to service or labour under limited circumstances, as per the United States v. Kozminski case.

Japan's Post-War Constitution: A New Beginning?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fugitive slave laws and the right to reclaim runaways

Fugitive slave laws gave slave owners the right to reclaim runaway slaves from other states. The U.S. Constitution included a Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or Fugitives from Labor Clause, which required a "person held to Service or Labour" (usually a slave, apprentice, or indentured servant) who fled to another state to be returned to their master. The Clause, which was Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, did not mention the word "slave" but nevertheless formed the basis for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which gave slaveholders the explicit right to capture enslaved persons who ran away. The Act clarified the processes by which slave owners could claim their property and was designed to balance the competing interests of free and slave states.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was met with a lot of criticism, especially in the Northern states, where many argued that the law was tantamount to legalized kidnapping. Despite this, the Act remained largely unenforced, and by the mid-19th century, thousands of enslaved people had escaped to free states via networks like the Underground Railroad. In response to pressure from Southern politicians, Congress passed a revised Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which gave the federal government a role in capturing fugitive enslaved persons and required escaped slaves in any state to be returned to their owners. This Act was also met with widespread resistance and criticism, with several Northern states enacting "personal liberty laws" to protect their residents from kidnapping and provide safeguards for accused fugitives.

The Fugitive Slave Clause and the Fugitive Slave Acts were rendered mostly irrelevant by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery except as a punishment for criminal acts. However, it is worth noting that even after the abolition of slavery, people can still be held to service or labour under limited circumstances, as noted in the United States v. Kozminski case.

Who Decides What the Constitution Means?

You may want to see also

Fugitive Slave Clause and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. It requires that a "Person held to Service or Labour" who escapes to another state must be returned to their master in the state they originally escaped from. The clause does not use the words "slave" or "slavery", and historian Donald Fehrenbacher believes that the Constitution intended to make it clear that slavery was only legal under state law, not federal.

Modern legal scholars debate whether the Fugitive Slave Clause gave constitutional legitimacy to slavery. Some argue that its wording was a political compromise, while others say it entrenched slaveholder power. The Clause remained in effect until the abolition of slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was written to enforce the Fugitive Slave Clause, giving slaveholders the right to capture enslaved people who had run away to free states. However, many free states wanted to disregard the Act, and some passed personal liberty laws to protect free Black residents and provide safeguards for accused fugitives. The Supreme Court case of Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) ruled that states did not have to aid in the recapture of enslaved people, weakening the law.

In response to this weakening of the original Fugitive Slave Act, Democratic Senator James M. Mason of Virginia drafted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This Act was part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers. It was highly controversial and contributed to the growing divide over slavery in the country. The Act required that escaped slaves be returned to their owners and that officials and citizens of free states cooperate in their capture. It also made the federal government responsible for finding, returning, and trying escaped slaves. Law enforcement officials were required to arrest people suspected of escaping slavery on as little as a claimant's sworn testimony of ownership, and could be fined $1,000 (equivalent to $37,800 in 2024) for failing to do so. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it much harder for enslaved people to escape, particularly in states close to the North.

The Constitution's Birthplace: Where History Was Written

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or Fugitives From Labour Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. It requires that any "Person held to Service or Labour" who escapes to another state must be returned to their master.

The Fugitive Slave Clause was used as the basis for the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, which provided slaveholders with the legal right to reclaim their slaves from other states. The 1850 Act also made the federal government responsible for finding and returning escaped slaves.

No, the word "slave" was not mentioned in the Fugitive Slave Clause. This was a deliberate decision to avoid overtly validating slavery at the federal level.

No, the Fugitive Slave Clause has been made mostly irrelevant by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery except as punishment for criminal acts.