Political parties are organized groups of individuals who share common ideologies, interests, and goals, and who work together to influence government policies, gain political power, and represent their supporters in the political process. At their core, these parties serve as intermediaries between the government and the public, aggregating diverse viewpoints into coherent platforms and competing in elections to shape the direction of a country's governance. They play a crucial role in democratic systems by fostering political participation, mobilizing voters, and providing a structured framework for debate and decision-making, ultimately ensuring that various segments of society have a voice in the political arena.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Organized groups that seek to influence government policy and leadership. |

| Purpose | To gain political power, implement policies, and represent voter interests. |

| Membership | Comprised of individuals with shared political beliefs and goals. |

| Ideology | Guided by a specific set of principles, values, or policies. |

| Leadership | Led by elected or appointed officials who make strategic decisions. |

| Structure | Hierarchical, with local, regional, and national branches. |

| Funding | Supported by donations, membership fees, and public funding in some cases. |

| Campaigning | Engage in elections, rallies, and media outreach to gain support. |

| Representation | Act as intermediaries between citizens and government. |

| Policy Formation | Develop and advocate for specific policies to address societal issues. |

| Accountability | Held accountable by voters, media, and internal party mechanisms. |

| Diversity | May represent diverse demographic, economic, or social groups. |

| Legal Status | Recognized and regulated by national laws in most democracies. |

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Political Parties: Historical emergence and evolution of organized political groups in democratic societies

- Core Functions: Mobilizing voters, aggregating interests, and forming governments to implement policies

- Ideological Basis: Parties often represent specific beliefs, values, or visions for societal governance

- Structural Organization: Leadership, membership, and hierarchical frameworks within party systems

- Role in Democracy: Facilitating representation, competition, and accountability in political systems

Origins of Political Parties: Historical emergence and evolution of organized political groups in democratic societies

The concept of political parties as we know them today is a relatively modern phenomenon, with roots tracing back to the 17th and 18th centuries. In the early stages of democratic societies, particularly in England and the United States, factions began to form around shared ideologies and interests. These factions were often loosely organized groups of like-minded individuals who sought to influence government policies and decisions. For instance, the Whigs and Tories in England emerged as early precursors to modern political parties, representing distinct interests and philosophies. Similarly, in the United States, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties arose during the late 18th century, marking the beginning of organized political competition.

The evolution of political parties was closely tied to the expansion of suffrage and the democratization of political systems. As voting rights extended beyond the elite to include a broader segment of the population, the need for organized groups to mobilize and represent diverse interests became apparent. This period saw the transformation of informal factions into more structured parties with defined platforms, leadership hierarchies, and mechanisms for candidate selection. For example, the introduction of party conventions in the United States during the 19th century formalized the process of nominating presidential candidates, solidifying the role of parties in the electoral process.

A comparative analysis of early political parties reveals both similarities and differences across democratic societies. In France, the post-Revolutionary period saw the emergence of parties like the Girondins and Jacobins, which were deeply ideological and often polarized. In contrast, British parties evolved more gradually, with a focus on pragmatic governance rather than rigid ideology. These variations highlight how historical context, cultural norms, and institutional structures shaped the development of political parties. For instance, the two-party system in the United States contrasts with the multi-party systems in countries like Germany and India, reflecting differing societal and political dynamics.

The historical emergence of political parties also underscores their role as essential mechanisms for aggregating interests and facilitating governance. By organizing citizens around common goals, parties simplify the political landscape, making it easier for voters to make informed choices. However, this evolution was not without challenges. Early parties often faced criticism for fostering division and prioritizing partisan interests over the common good. For example, the spoils system in 19th-century America, where party loyalists were rewarded with government jobs, highlighted the potential for corruption and inefficiency.

To understand the origins of political parties, consider the following practical takeaway: their development was a response to the complexities of democratic governance. As societies grew more diverse and political systems more inclusive, parties emerged as vital tools for representation and mobilization. Today, while their structures and functions have evolved, their core purpose remains unchanged—to bridge the gap between citizens and the state. For those studying political systems, examining the historical emergence of parties offers valuable insights into the dynamics of democracy and the challenges of balancing unity with diversity.

Unraveling Hamilton's Political Allegiances: Federalist or Democratic-Republican?

You may want to see also

Core Functions: Mobilizing voters, aggregating interests, and forming governments to implement policies

Political parties are the backbone of democratic systems, serving as essential mechanisms for organizing political life. At their core, they perform three critical functions: mobilizing voters, aggregating interests, and forming governments to implement policies. These functions are not just theoretical constructs but practical tools that shape the political landscape. Without them, the chaos of individual interests and voices would overwhelm the democratic process, making governance nearly impossible.

Consider the act of mobilizing voters, a function that transforms passive citizens into active participants. Political parties achieve this through campaigns, rallies, and door-to-door outreach, often leveraging data analytics to target specific demographics. For instance, during the 2020 U.S. presidential election, both major parties used micro-targeting strategies to engage younger voters, a group historically less likely to vote. This mobilization is not just about increasing turnout; it’s about channeling collective energy toward a shared vision. However, this function carries risks, such as polarizing voters through divisive messaging or alienating undecided voters with overly aggressive tactics. Parties must balance enthusiasm with inclusivity to avoid fracturing the electorate.

Aggregating interests is another cornerstone function, where parties act as intermediaries between diverse groups and the government. By synthesizing disparate demands—such as labor rights, environmental protections, or tax reforms—parties create coherent platforms that appeal to broad coalitions. For example, the Green Party in Germany has successfully aggregated environmental interests, influencing national policies on renewable energy. Yet, this function is fraught with challenges. Parties often face pressure to prioritize the interests of their most vocal or financially influential supporters, potentially marginalizing smaller groups. Effective aggregation requires a delicate balance between responsiveness and representation, ensuring no single interest dominates the agenda.

The final function—forming governments to implement policies—is where the rubber meets the road. Once elected, parties translate campaign promises into actionable governance. This involves coalition-building, legislative negotiation, and executive decision-making. Take the example of Sweden’s Social Democratic Party, which has historically formed governments by aligning with smaller parties to pass welfare policies. However, this function is not without pitfalls. Policy implementation often requires compromise, which can dilute the original vision. Additionally, parties in power may face backlash if their actions fail to meet voter expectations, as seen in the decline of the Labour Party in the UK post-2010 due to austerity measures.

In practice, these core functions are interdependent. Mobilizing voters without aggregating their interests leads to hollow campaigns, while aggregating interests without forming governments renders those efforts futile. Parties must master all three to remain relevant and effective. For instance, a party that excels at mobilization but fails to deliver on policy promises risks losing voter trust, as evidenced by the decline of populist movements in some European countries. Conversely, a party that governs effectively but loses touch with its base risks becoming disconnected from the electorate. The art lies in harmonizing these functions, ensuring each reinforces the others in a dynamic, responsive system.

Ultimately, the core functions of political parties are not just about winning elections but about sustaining democracy. They provide structure to political participation, ensure diverse voices are heard, and enable the execution of policies that shape societies. However, their success depends on adaptability—navigating the tensions between competing interests, maintaining voter trust, and delivering tangible results. In an era of shifting political landscapes, parties that master these functions will remain indispensable, while those that fail risk obsolescence.

Nigel Farage's Political Party Affiliation: Unraveling His Current Allegiance

You may want to see also

Ideological Basis: Parties often represent specific beliefs, values, or visions for societal governance

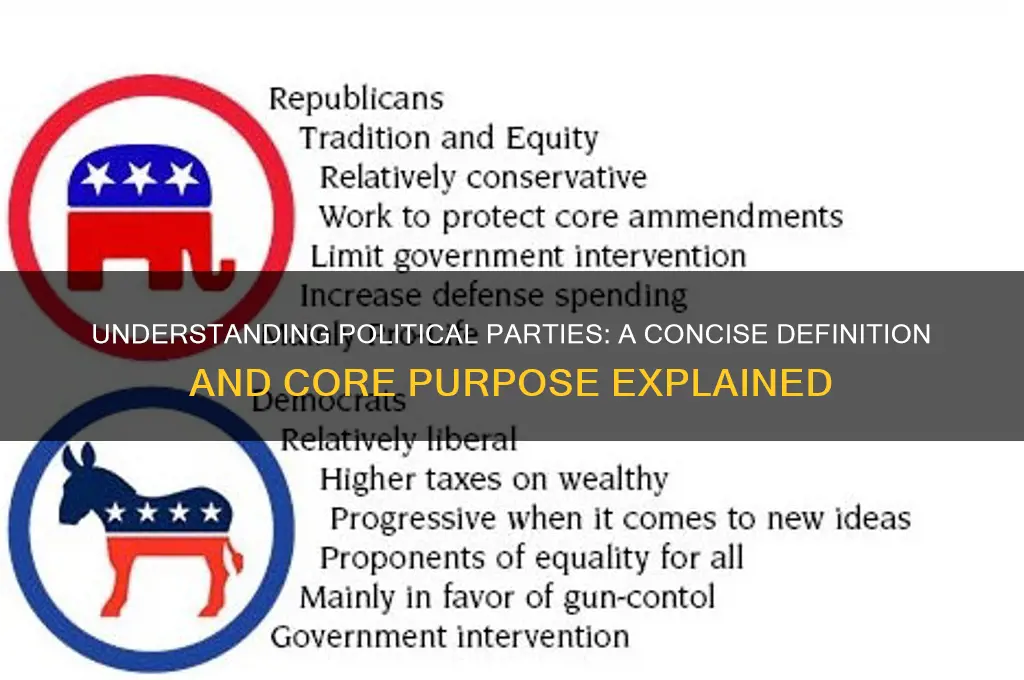

Political parties are not merely vehicles for power; they are the embodiment of ideologies that shape societies. At their core, these organizations crystallize complex beliefs, values, and visions into actionable platforms. Consider the Democratic Party in the United States, which champions progressive ideals like social equity, healthcare access, and environmental sustainability. In contrast, the Republican Party emphasizes limited government, free-market capitalism, and individual liberty. These ideological frameworks serve as compasses, guiding policy decisions and rallying supporters around shared principles.

To understand the ideological basis of political parties, think of them as architects of societal blueprints. Each party designs its vision for governance, addressing fundamental questions: How should resources be distributed? What role should the state play in personal freedoms? For instance, socialist parties advocate for collective ownership of resources, while libertarian parties prioritize minimal state intervention. These visions are not abstract; they manifest in tangible policies, such as taxation rates, education systems, and foreign relations. By aligning with a party, individuals endorse a specific roadmap for societal progress.

However, ideological purity is often a myth. Parties must balance their core beliefs with practical politics, especially in diverse democracies. Take the Labour Party in the UK, which historically rooted itself in socialist principles but has shifted toward a more centrist stance to appeal to a broader electorate. This pragmatism can dilute ideological clarity but ensures electoral viability. Critics argue this compromises the party’s identity, while proponents see it as necessary for governance. This tension highlights the challenge of maintaining ideological integrity in a dynamic political landscape.

For those seeking to engage with political parties, understanding their ideological basis is crucial. Start by examining party manifestos, which outline their core values and policy goals. Compare these documents across parties to identify where they converge or diverge. For example, while both the Green Party and the Conservative Party may address environmental issues, their approaches differ radically—one advocating for radical systemic change, the other for market-driven solutions. This analysis empowers voters to make informed choices and activists to align with parties that genuinely reflect their beliefs.

In essence, the ideological basis of political parties is their lifeblood, defining their purpose and direction. It is not just about winning elections but about advancing a vision for society. Whether you are a voter, a policymaker, or a casual observer, recognizing this ideological core transforms political engagement from a passive act into an active participation in shaping the future. After all, parties are not just names on a ballot—they are the architects of the world we inhabit.

Alexander Hamilton's Political Affiliation: Federalist Party Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.07 $24.95

Structural Organization: Leadership, membership, and hierarchical frameworks within party systems

Political parties are not just collections of individuals with shared ideologies; they are structured organizations designed to achieve specific political goals. At the heart of their structural organization lies a complex interplay of leadership, membership, and hierarchical frameworks. These elements determine how decisions are made, power is distributed, and the party functions as a cohesive unit.

Consider the leadership of a political party, often the most visible aspect of its structure. Leaders can range from charismatic figureheads who embody the party’s values to strategic managers focused on operational efficiency. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States has seen leaders like Franklin D. Roosevelt, who reshaped the party’s ideology during the New Deal era, and more recently, figures like Nancy Pelosi, who excel in legislative strategy and coalition-building. Effective leadership not only sets the party’s agenda but also ensures alignment between its core principles and practical policies. However, over-reliance on a single leader can lead to vulnerabilities, as seen in parties where the absence of a strong figurehead results in internal fragmentation.

Membership is another critical component, forming the party’s base and influencing its direction. Members can range from grassroots activists to financial contributors, each playing distinct roles. In Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), for example, members participate in local chapters, shaping policy proposals and electing delegates for party conventions. This decentralized approach fosters inclusivity but can also slow decision-making. Conversely, parties with restricted membership, like the British Conservative Party, often prioritize elite control, ensuring quicker responses to political shifts. The balance between inclusivity and efficiency is a recurring challenge in party organization.

Hierarchical frameworks dictate how power flows within a party, from national leadership to local branches. The Indian National Congress operates with a multi-tiered structure, where state and district committees report to the central leadership, ensuring uniformity in messaging and strategy. In contrast, the Labour Party in the UK has experimented with flatter hierarchies, empowering local constituencies to influence national policy. Such frameworks are not static; they evolve in response to internal dynamics and external pressures. For instance, parties facing electoral setbacks often decentralize to reinvigorate grassroots engagement, while those in power may centralize to maintain control.

Understanding these structural elements is crucial for anyone analyzing or participating in party politics. Leadership sets the tone, membership provides the foundation, and hierarchies determine operational efficiency. Together, they shape a party’s ability to mobilize support, win elections, and implement policies. For practitioners, recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of different models can inform strategic decisions, such as whether to prioritize unity or diversity in leadership, or how to balance grassroots input with centralized decision-making. In the ever-changing landscape of politics, a party’s structural organization is not just a blueprint—it’s a dynamic tool for survival and success.

NJ Political Party Switch: Understanding the Timeline for Affiliation Change

You may want to see also

Role in Democracy: Facilitating representation, competition, and accountability in political systems

Political parties are essential mechanisms for aggregating interests and structuring political competition, serving as intermediaries between citizens and government. In democratic systems, their role extends beyond mere organization—they facilitate representation, foster competition, and ensure accountability, each function critical to the health and efficacy of democracy. Without these parties, the complexity of modern governance would overwhelm direct citizen participation, leaving democracy vulnerable to fragmentation and inefficiency.

Consider representation: political parties act as vehicles for translating diverse societal interests into coherent policy platforms. By grouping individuals with shared ideologies, parties simplify the political landscape, allowing voters to identify and support agendas that align with their values. For instance, in the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties broadly represent progressive and conservative interests, respectively, enabling citizens to engage meaningfully in the political process without needing expertise in every policy area. This aggregation of interests is particularly vital in large, heterogeneous societies where direct representation of every individual viewpoint is impractical.

Competition, another cornerstone of democracy, is inherently driven by political parties. They provide a structured framework for contesting power, ensuring that elections are not merely ceremonial but genuine contests of ideas and leadership. In countries like India, with its multi-party system, parties compete fiercely at national and regional levels, fostering a dynamic political environment that reflects the diversity of its population. This competition incentivizes parties to innovate, adapt, and remain responsive to public demands, preventing stagnation and monopolization of power.

Accountability, the third pillar, is enforced through the mechanisms parties create for oversight and opposition. In parliamentary systems, such as the United Kingdom, the opposition party formally scrutinizes the ruling party’s actions, ensuring transparency and limiting abuses of power. Similarly, in presidential systems, parties out of power often act as watchdogs, using media and legislative tools to hold the executive branch accountable. This checks-and-balances role is crucial for maintaining public trust and preventing authoritarian tendencies.

However, the effectiveness of parties in fulfilling these roles depends on their internal health and external environment. Parties must remain inclusive, avoiding capture by narrow elites or special interests, to ensure genuine representation. They must also operate within a fair electoral framework that encourages competition rather than suppressing it. For instance, proportional representation systems tend to foster multi-party competition, while winner-takes-all systems can lead to dominance by a few parties, reducing accountability.

In practice, strengthening these roles requires deliberate action. Citizens should engage with parties beyond election cycles, participating in primaries, caucuses, or internal elections to shape party platforms. Governments can enhance competition by reforming campaign finance laws to reduce the influence of money in politics. Finally, media and civil society play a critical role in holding parties accountable by amplifying public concerns and exposing misconduct. By understanding and actively supporting these functions, stakeholders can ensure that political parties remain robust facilitators of democratic governance.

Political Parties: Pillars of Stability in Democratic Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties are organized groups of people who share common political goals, ideologies, or interests and work together to gain political power, influence government policies, and represent their supporters in the political process.

Political parties are essential in democracies as they aggregate interests, mobilize voters, provide a platform for political participation, and facilitate the formation of governments by competing for electoral support.

Political parties typically form around shared ideologies, policies, or leaders. They operate through internal structures like leadership committees, membership networks, and campaigns to promote their agenda and win elections.

Political parties play roles such as shaping public policy, holding governments accountable, representing diverse interests, and providing a mechanism for peaceful transitions of power through elections.

While political parties are most prominent in democratic systems, they can also exist in authoritarian regimes, though their functions and autonomy are often restricted or controlled by the ruling authority.