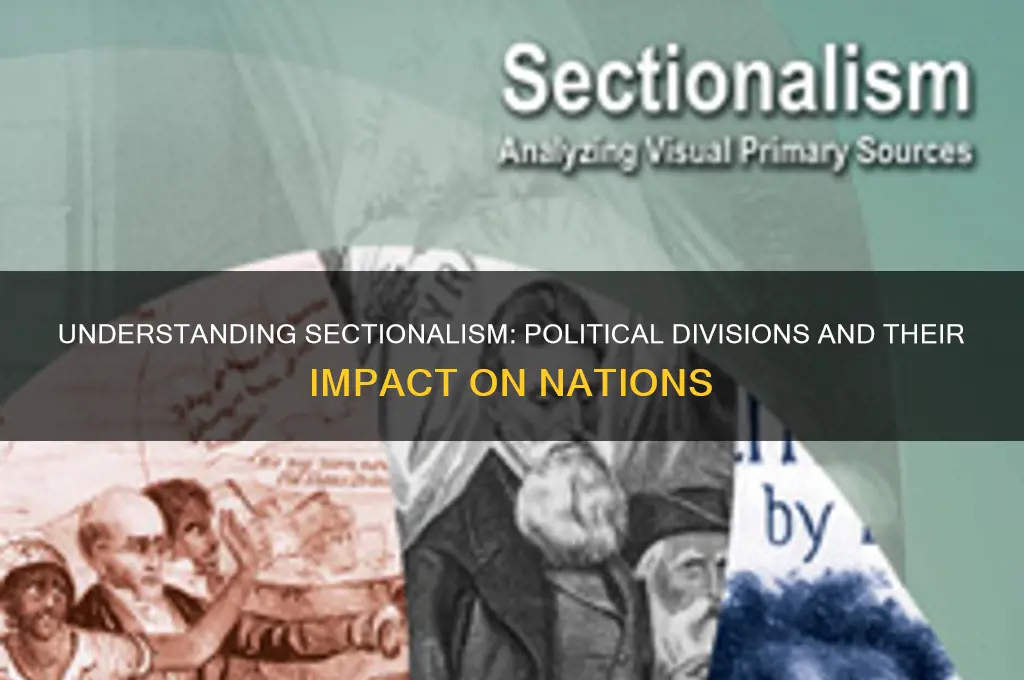

Sectionalism in politics refers to the loyalty to the interests of one’s own region or section of a country over the interests of the nation as a whole. It often arises when distinct geographic areas within a country develop unique economic, social, or cultural identities that clash with those of other regions. This phenomenon can lead to political divisions, as local priorities and ideologies shape policy preferences, sometimes at the expense of national unity. Historically, sectionalism has been a significant factor in shaping political conflicts, such as debates over slavery in the United States or regional autonomy in multinational states. Understanding sectionalism is crucial for analyzing how regional differences influence national politics and governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Sectionalism refers to the loyalty to local or regional interests over national interests, often leading to political divisions. |

| Historical Context | Prominent in 19th-century U.S. (e.g., North vs. South over slavery) and in modern multi-ethnic or geographically diverse nations. |

| Economic Disparities | Regions prioritize local economic benefits, often at the expense of national policies (e.g., resource allocation, trade). |

| Cultural and Social Differences | Regional identities (e.g., language, religion, traditions) drive political agendas, fostering division. |

| Political Polarization | Parties or leaders exploit regional grievances to gain support, deepening national divides. |

| Resource Competition | Disputes over natural resources (e.g., water, land) lead to regional conflicts and resistance to federal intervention. |

| Legislative Gridlock | Regional interests hinder national policy-making, resulting in stalemates in parliament or congress. |

| Identity Politics | Regional identity becomes a primary political driver, overshadowing broader national unity. |

| Media and Propaganda | Local media amplifies regional narratives, reinforcing sectional divides and mistrust of other regions. |

| Globalization Resistance | Regions resist global or national policies perceived as threatening local autonomy or traditions. |

| Modern Examples | Catalonia (Spain), Flanders (Belgium), or red vs. blue state divides in the U.S. showcase contemporary sectionalism. |

Explore related products

$24.71 $36.99

$14.78 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Regional Identities: How geographic areas develop distinct political, cultural, and economic characteristics

- Economic Interests: Conflicts arising from differing regional economic priorities and resource distribution

- Policy Divisions: Disagreements over federal versus state rights and legislative priorities

- Historical Roots: Origins of sectionalism in historical events, slavery, and industrialization

- Modern Manifestations: How sectionalism influences contemporary political polarization and regional voting patterns

Regional Identities: How geographic areas develop distinct political, cultural, and economic characteristics

Sectionalism in politics refers to the loyalty to the interests of one’s own region or section of the country over the interests of the nation as a whole. This phenomenon often arises from the distinct political, cultural, and economic characteristics that geographic areas develop over time. Regional identities play a pivotal role in shaping sectionalism, as they foster a sense of uniqueness and solidarity among residents of a particular area. These identities are forged through shared histories, environmental factors, and socio-economic conditions, which collectively influence how a region perceives itself and its place within the broader national context.

Geography itself is a fundamental driver of regional identities. Physical features such as mountains, rivers, and coastlines can isolate communities, encouraging the development of distinct cultures and economies. For example, coastal regions often rely on maritime industries like fishing and trade, while inland areas may focus on agriculture or manufacturing. These economic differences create divergent interests and priorities, which can manifest in political attitudes. A region dependent on coal mining, for instance, may strongly oppose environmental regulations that threaten its economic base, while a tech-heavy region might advocate for policies promoting innovation and education.

Cultural practices and traditions also contribute to regional identities. Historical events, immigration patterns, and local customs shape the values and beliefs of a region’s inhabitants. In the United States, the South’s history of slavery and the Civil War has left a lasting cultural imprint, influencing its political leanings and social attitudes. Similarly, the Midwest’s agricultural heritage has fostered a culture of self-reliance and conservatism, which often translates into political preferences. These cultural distinctions can deepen sectional divides, as regions may view national policies through the lens of their unique experiences and values.

Economic disparities between regions further exacerbate sectionalism. Wealthier areas may advocate for policies that protect their economic advantages, while less affluent regions push for redistribution and investment. For instance, urban centers with thriving economies might support free trade agreements, while rural areas suffering from deindustrialization may favor protectionist measures. These economic tensions can lead to political polarization, as regions compete for resources and influence at the national level. The perception that one’s region is being neglected or exploited by national policies can fuel resentment and strengthen regional identities.

Political institutions and governance structures also play a role in reinforcing regional identities. Federal systems, like those in the United States or India, often grant significant autonomy to states or provinces, allowing them to develop policies tailored to their specific needs. This decentralization can both reflect and deepen regional differences, as local governments prioritize their constituents’ interests over national unity. Additionally, political parties and movements frequently emerge to represent regional grievances, further entrenching sectionalism in the political landscape.

In conclusion, regional identities are shaped by a complex interplay of geographic, cultural, economic, and political factors. These identities are not static but evolve in response to changing circumstances, yet they remain a powerful force in shaping sectionalism. Understanding how geographic areas develop distinct characteristics is essential for comprehending the dynamics of sectionalism in politics. It highlights the challenges of balancing regional interests with national cohesion and underscores the importance of inclusive policies that address the diverse needs of all regions.

Political Apathy: A Silent Revolution for Individual Freedom and Peace

You may want to see also

Economic Interests: Conflicts arising from differing regional economic priorities and resource distribution

Sectionalism in politics refers to the loyalty to the interests of one’s own region or section of the country over the nation as a whole, often leading to conflicts based on economic, social, or cultural differences. At its core, Economic Interests play a pivotal role in driving sectionalism, as regions with distinct economic priorities and resource distributions clash over policies, investments, and national strategies. These conflicts arise because different regions rely on unique industries, resources, and labor systems, which shape their economic agendas and perceptions of fairness in resource allocation.

One of the most prominent examples of economic sectionalism is the historical divide between industrialized regions and agricultural regions. Industrialized areas, often concentrated in urban centers, prioritize manufacturing, trade, and technological advancement. They advocate for policies like tariffs to protect domestic industries, infrastructure development, and labor regulations. In contrast, agricultural regions, typically rural, depend on farming, ranching, and commodity exports. They push for free trade to access global markets, subsidies for farmers, and policies that reduce production costs. This clash of interests can lead to legislative gridlock, as seen in debates over farm bills or trade agreements, where one region’s gain is perceived as another’s loss.

Resource distribution further exacerbates economic sectionalism, particularly in regions rich in natural resources like coal, oil, timber, or water. For instance, resource-rich states may advocate for deregulation to maximize extraction and profits, while other regions prioritize environmental protection and sustainable practices. This tension is evident in debates over energy policies, such as fossil fuel subsidies versus renewable energy investments. Regions dependent on resource extraction often resist policies that threaten their economic base, even if those policies align with national environmental goals or benefit other sections of the country.

Labor markets also contribute to economic sectionalism, as regions with differing workforce demographics and industries compete for jobs and economic growth. For example, regions with a high concentration of low-wage workers may support policies that restrict immigration to protect local jobs, while regions facing labor shortages advocate for more open immigration policies. Similarly, areas with a strong tech or service sector may push for education and innovation funding, while manufacturing-heavy regions prioritize retraining programs for displaced workers. These competing priorities create friction, as national policies often favor one region’s workforce over another.

Finally, federal spending and taxation are recurring flashpoints in economic sectionalism. Regions that contribute more in taxes than they receive in federal funding often resent what they perceive as subsidizing other regions. This dynamic fuels debates over fiscal policies, such as progressive taxation, welfare programs, and infrastructure projects. Wealthier regions may argue for fiscal restraint and local control, while economically disadvantaged regions demand greater federal investment to address inequality. Such conflicts highlight how economic interests shape regional identities and political alliances, often at the expense of national unity.

In summary, economic interests are a primary driver of sectionalism, as regions with differing economic priorities and resource distributions vie for policies that benefit their local economies. These conflicts manifest in debates over industry protection, resource management, labor policies, and fiscal allocation, underscoring the challenge of balancing regional interests with national cohesion. Understanding these dynamics is essential to addressing the root causes of sectionalism and fostering more equitable economic policies.

Are Political Parties Beneficial or Detrimental to Democracy?

You may want to see also

Policy Divisions: Disagreements over federal versus state rights and legislative priorities

Sectionalism in politics refers to the loyalty to the interests of one’s own region or section of the country over the interests of the nation as a whole. In the context of policy divisions, disagreements over federal versus state rights and legislative priorities are central to understanding how sectionalism manifests. These disputes often arise when regions prioritize their unique economic, social, or cultural needs, leading to conflicts over the balance of power between the federal government and state governments. Such divisions can hinder national unity and complicate the implementation of cohesive policies.

One of the most persistent policy divisions revolves around the interpretation of federal versus state authority. Advocates for states' rights argue that the Constitution limits federal power, emphasizing the Tenth Amendment's reservation of powers to the states or the people. This perspective often aligns with regions seeking autonomy in areas like education, healthcare, and environmental regulation. In contrast, proponents of federal authority contend that a strong central government is necessary to ensure uniformity in critical areas such as civil rights, interstate commerce, and national security. This ideological clash frequently results in legal battles, with landmark Supreme Court cases often defining the boundaries of federal and state powers.

Legislative priorities further exacerbate these divisions, as different regions have distinct needs and values. For example, agricultural states may push for policies favoring rural development and subsidies, while urbanized states prioritize infrastructure and public transportation funding. Similarly, states with significant natural resources might advocate for deregulation to boost local industries, whereas environmentally conscious regions may lobby for stricter federal regulations to combat climate change. These competing priorities often lead to gridlock in Congress, as representatives and senators champion policies benefiting their constituents at the expense of national compromise.

The tension between federal and state authority is also evident in social and cultural policies. Issues like abortion, gun control, and LGBTQ+ rights are frequently polarized along regional lines, with states enacting laws that reflect local sentiments. For instance, conservative states may pass restrictive abortion laws, while liberal states codify protections for reproductive rights. This patchwork of policies creates inconsistencies across the nation, prompting federal intervention in some cases and reinforcing states' rights in others. The result is a fragmented policy landscape that reflects sectional interests rather than a unified national approach.

Ultimately, policy divisions over federal versus state rights and legislative priorities highlight the challenges of balancing regional autonomy with national cohesion. Sectionalism in this context underscores the difficulty of crafting policies that satisfy diverse and often conflicting interests. While federalism allows states to serve as laboratories of democracy, experimenting with different approaches to governance, it also risks deepening regional divides. Addressing these divisions requires a delicate balance between respecting states' rights and ensuring that federal policies promote fairness, equity, and the common good across all regions.

Political Patronage: Who Benefits and How It Shapes Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical Roots: Origins of sectionalism in historical events, slavery, and industrialization

Sectionalism in American politics has deep historical roots, with its origins intertwined with pivotal events, the institution of slavery, and the process of industrialization. The early years of the United States saw the emergence of distinct regional identities, primarily between the North and the South, which laid the groundwork for sectional tensions. These divisions were not merely geographical but were shaped by differing economic systems, social structures, and cultural values. The North, with its burgeoning industrial economy, contrasted sharply with the South’s agrarian, slave-dependent society. This economic divergence became a cornerstone of sectionalism, as each region sought to advance its own interests, often at the expense of national unity.

One of the most significant historical events that fueled sectionalism was the debate over slavery. The Three-Fifths Compromise of 1787, which counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for representation and taxation purposes, was an early indication of the compromises made to balance the interests of slave and free states. However, as the nation expanded westward, the question of whether new states would permit slavery became increasingly contentious. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 temporarily eased tensions by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, but it also highlighted the growing divide between the North and South. The issue of slavery was not just moral but also economic, as it underpinned the Southern economy and was vehemently opposed by many in the North, where industrialization and wage labor predominated.

The industrialization of the North further exacerbated sectional tensions. The North’s rapid economic growth, fueled by manufacturing, railroads, and urbanization, created a stark contrast with the South’s reliance on agriculture and enslaved labor. Northern industrialists and workers viewed slavery as an outdated and morally repugnant institution that hindered national progress. Meanwhile, Southern planters saw Northern industrialization and its accompanying political and economic policies, such as tariffs, as threats to their way of life. The Tariff of 1828, known as the "Tariff of Abominations" in the South, imposed high taxes on imported goods, benefiting Northern manufacturers but burdening Southern consumers and planters who relied on international trade. This economic disparity deepened the rift between the regions.

The expansion of the United States through territorial acquisitions and westward migration also played a crucial role in the origins of sectionalism. The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) and the subsequent acquisition of vast territories reignited the debate over the extension of slavery into new states. The Compromise of 1850, which included the Fugitive Slave Act, was another attempt to maintain balance but instead intensified Northern opposition to slavery and Southern fears of encroachment on their rights. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by allowing popular sovereignty to decide the status of slavery in new territories, led to violent conflicts like "Bleeding Kansas," further polarizing the nation.

In summary, the historical roots of sectionalism in American politics are deeply embedded in the institution of slavery, the process of industrialization, and key historical events that highlighted regional differences. These factors created competing economic, social, and ideological interests between the North and South, setting the stage for decades of conflict and ultimately contributing to the outbreak of the Civil War. Understanding these origins is essential to grasping the enduring impact of sectionalism on American political identity and unity.

Unveiling the Origins: Who Created Red Alert Politics?

You may want to see also

Modern Manifestations: How sectionalism influences contemporary political polarization and regional voting patterns

Sectionalism in politics refers to the loyalty to the interests of one’s own region or section of the country over the interests of the nation as a whole. Historically, it has been a driving force behind political divisions, often rooted in economic, cultural, or social differences between regions. In contemporary politics, sectionalism continues to play a significant role in shaping political polarization and regional voting patterns. Modern manifestations of sectionalism are evident in the deepening ideological divides between urban and rural areas, the South and the Northeast, and states with distinct economic bases, such as those reliant on fossil fuels versus those focused on technology and green energy. These divisions are amplified by partisan politics, media echo chambers, and the strategic use of regional identities by political leaders.

One of the most prominent ways sectionalism influences contemporary politics is through the stark contrast in voting patterns between urban and rural regions. Urban areas, often characterized by greater diversity, higher education levels, and a focus on progressive policies like climate change and social justice, tend to lean Democratic. In contrast, rural areas, which frequently prioritize issues like gun rights, traditional values, and local economic concerns, overwhelmingly vote Republican. This urban-rural divide is not merely a reflection of policy preferences but also a manifestation of sectionalism, as each region perceives its interests as distinct and often at odds with the other. The 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections highlighted this divide, with cities and their suburbs voting blue while rural counties turned deep red, creating a geographic and ideological chasm.

Regional identities also play a critical role in modern sectionalism, particularly in the United States. The South, for example, has long been a stronghold of conservatism, shaped by its history, culture, and economic interests. States in this region consistently vote Republican in national elections, driven by issues like states' rights, religious values, and resistance to federal intervention. Conversely, the Northeast and West Coast, with their strong labor unions, diverse populations, and emphasis on progressive policies, remain Democratic bastions. These regional voting patterns are not accidental but are deeply rooted in sectional loyalties that transcend individual candidates or short-term political issues. Political parties often exploit these regional identities, tailoring their messaging to resonate with specific sectional interests.

Economic sectionalism further exacerbates political polarization by aligning regional economic interests with partisan politics. For instance, states heavily reliant on industries like coal or oil, such as West Virginia or Texas, often support Republican policies that favor deregulation and fossil fuel expansion. In contrast, states with economies centered on technology, renewable energy, or finance, like California or New York, align with Democratic policies promoting innovation and environmental sustainability. This economic sectionalism creates a feedback loop where regional economic interests reinforce political allegiances, making it harder for cross-party cooperation. The result is a political landscape where regional economic priorities dictate voting behavior, deepening the divide between sections of the country.

Finally, media and technology have become powerful tools in amplifying sectionalism and its impact on political polarization. Regional media outlets and social media platforms often cater to specific sectional identities, reinforcing existing biases and creating echo chambers. For example, conservative media in the South may focus on issues like border security or religious freedom, while progressive outlets in the Northeast emphasize social justice or climate action. This targeted messaging strengthens sectional loyalties and makes it difficult for voters to find common ground. Additionally, gerrymandering and the concentration of like-minded voters in specific districts further entrench sectionalism, as politicians are incentivized to appeal to regional interests rather than national unity.

In conclusion, sectionalism remains a powerful force in contemporary politics, shaping political polarization and regional voting patterns in profound ways. The urban-rural divide, regional identities, economic interests, and the role of media all contribute to a political landscape where loyalty to one’s section often supersedes national cohesion. Understanding these modern manifestations of sectionalism is essential for addressing the root causes of polarization and fostering a more unified political environment.

Voting Without Affiliation: Do You Need to Declare a Political Party?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Sectionalism in politics refers to the loyalty to the interests of a specific region or section of a country, often at the expense of national unity or broader interests.

Sectionalism can lead to political polarization, as regional interests dominate decision-making, potentially undermining compromise and national cohesion.

Examples include the divide between the North and South in the United States leading up to the Civil War, driven by economic and ideological differences.

While sectionalism can highlight regional needs, it often exacerbates divisions and hinders collective progress, making it generally detrimental to national unity.