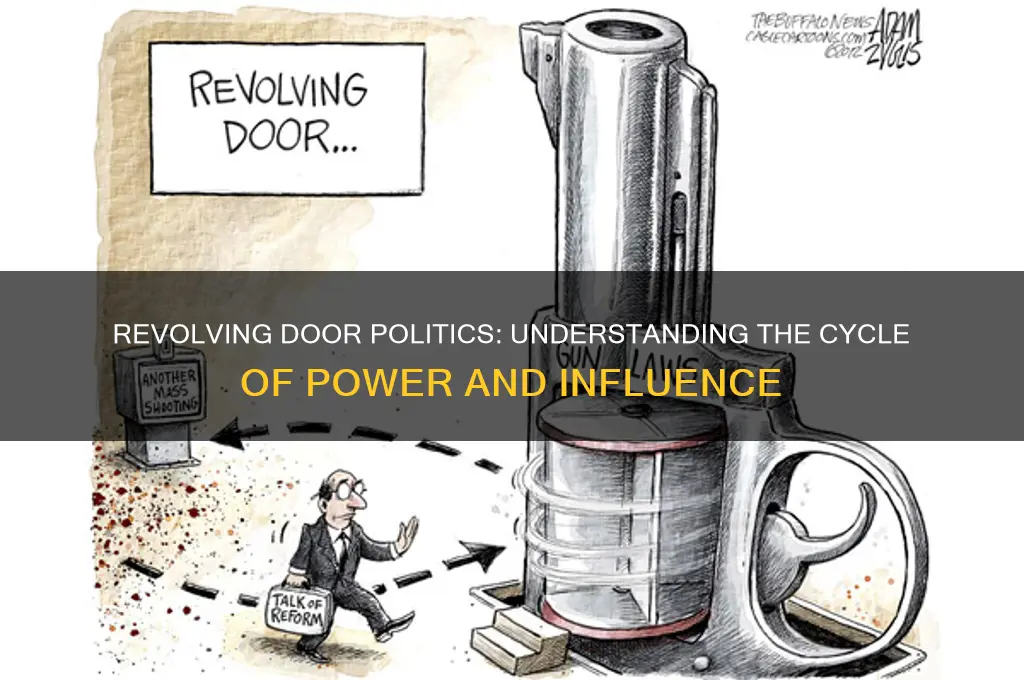

Revolving door politics refers to the phenomenon where individuals frequently move between roles in the public sector, such as government positions, and the private sector, often in industries they previously regulated. This cycle raises concerns about conflicts of interest, as former officials may leverage their government experience and connections to benefit private companies, while private sector executives may gain undue influence over public policy. Critics argue that this practice undermines transparency, accountability, and the integrity of democratic institutions, as it blurs the line between public service and corporate interests, potentially prioritizing profit over the public good.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The movement of individuals between roles as legislators, regulators, and private sector lobbyists or executives, often interchangeably. |

| Key Players | Former government officials, politicians, regulators, and corporate executives. |

| Primary Sectors | Government, lobbying firms, corporations, and regulatory agencies. |

| Purpose | To leverage insider knowledge, influence policy-making, and gain financial or career benefits. |

| Ethical Concerns | Conflicts of interest, undue corporate influence, and erosion of public trust in government. |

| Legal Framework | Varies by country; some have cooling-off periods or restrictions on post-government employment. |

| Examples | Former U.S. lawmakers becoming lobbyists, EU officials joining corporate boards. |

| Impact on Policy | Policies may favor corporate interests over public welfare due to industry influence. |

| Public Perception | Often viewed negatively as a form of corruption or elitism. |

| Global Prevalence | Common in democracies with strong corporate-government ties (e.g., U.S., EU, Japan). |

| Recent Trends | Increasing scrutiny and calls for stricter regulations to curb revolving door practices. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition: Briefly explain the concept of revolving door politics and its implications

- Examples: Highlight real-world cases of politicians transitioning between public and private sectors

- Ethical Concerns: Discuss conflicts of interest and potential corruption in revolving door practices

- Regulations: Explore laws and policies aimed at mitigating revolving door politics

- Impact: Analyze how revolving door politics affects governance, policy-making, and public trust

Definition: Briefly explain the concept of revolving door politics and its implications

Revolving door politics refers to the cyclical movement of individuals between roles in the public sector, particularly government, and the private sector, often in industries closely regulated by the government. This phenomenon is characterized by former government officials taking positions in private companies they once regulated, or executives from private firms moving into government roles overseeing their former industries. The term metaphorically likens this movement to a revolving door, where individuals exit one role only to re-enter a closely related one.

Consider the pharmaceutical industry, where a former Food and Drug Administration (FDA) official might join a drug company as a lobbyist or executive. This transition raises questions about divided loyalties and potential conflicts of interest. The official’s insider knowledge of regulatory processes could provide the company with an unfair advantage, while their prior government role might influence current regulators to favor their new employer. Such scenarios underscore the ethical and practical implications of revolving door politics.

The implications of this practice are far-reaching. Critics argue that it fosters regulatory capture, where government agencies prioritize industry interests over public welfare. For instance, a study by the Project on Government Oversight found that over 250 former congressional staffers became lobbyists within a year of leaving Capitol Hill, highlighting how this cycle can distort policy-making. Conversely, proponents claim it brings valuable expertise to both sectors, with private-sector experience informing public policy and vice versa. However, the lack of transparency and accountability often outweighs these benefits.

To mitigate risks, some countries have implemented cooling-off periods, requiring officials to wait before taking private-sector jobs related to their former roles. For example, the European Union mandates an 18-month cooling-off period for commissioners. In the U.S., the STOCK Act of 2012 aimed to curb insider trading by lawmakers but did little to address broader revolving door concerns. Practical steps for reform include extending cooling-off periods, strengthening disclosure requirements, and imposing stricter penalties for violations.

Ultimately, revolving door politics challenges the integrity of governance by blurring the line between public service and private gain. While it may facilitate knowledge transfer, the potential for corruption and undue influence demands robust safeguards. Policymakers, citizens, and watchdog groups must remain vigilant to ensure that the revolving door does not become a gateway for exploitation but remains a mechanism for balanced expertise—if managed responsibly.

Navigating Sensitive Conversations: How to Discuss Cancer with Compassion and Respect

You may want to see also

Examples: Highlight real-world cases of politicians transitioning between public and private sectors

The revolving door between public and private sectors is not just a metaphor—it’s a well-documented phenomenon. One striking example is the case of former U.S. Senator Phil Gramm. After co-authoring the Commodity Futures Modernization Act in 2000, which deregulated financial derivatives, Gramm left Congress in 2002 to become a vice chairman at UBS, a global financial services firm directly benefiting from the deregulation he championed. This transition illustrates how policy decisions can create lucrative pathways for politicians in the private sector, raising questions about conflicts of interest and the integrity of public service.

Across the Atlantic, the United Kingdom offers another illustrative case. Tony Blair, former Prime Minister, transitioned into a lucrative consulting career after leaving office, advising multinational corporations and foreign governments through his firm, Tony Blair Associates. While not illegal, this move sparked criticism for blurring the lines between public duty and private gain. Blair’s ability to leverage his political connections for financial benefit highlights the ethical gray areas inherent in revolving door politics, particularly when former leaders capitalize on their access to power networks.

In the realm of regulatory agencies, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides a recurring example. High-ranking officials often leave the FDA to join pharmaceutical companies they once regulated. For instance, Dr. Robert Temple, a long-time FDA official, joined the board of a drug company after retirement. While such transitions can bring valuable expertise to private firms, they also risk undermining public trust. The public may question whether regulatory decisions were influenced by the prospect of future employment, a concern that underscores the need for stricter post-employment restrictions.

A comparative analysis of these cases reveals a common thread: the lack of robust safeguards to prevent conflicts of interest. In the U.S., the “cooling-off period”—a mandatory wait time before former officials can lobby their previous agencies—is often criticized as insufficient. Similarly, the U.K.’s Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, which reviews post-public service jobs, has been accused of being too lenient. Strengthening these mechanisms, such as extending cooling-off periods and imposing stricter disclosure requirements, could mitigate the risks associated with revolving door politics.

Finally, consider the case of former European Commission President José Manuel Barroso, who joined Goldman Sachs as chairman of its international advisory board shortly after leaving office. This move drew widespread condemnation, as Goldman Sachs had been a key player in the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent eurozone debt crisis. Barroso’s transition exemplified how global financial institutions attract former policymakers, leveraging their insider knowledge for strategic advantage. Such cases underscore the need for international standards to regulate the revolving door, ensuring that public service remains a commitment to the common good rather than a stepping stone to private wealth.

Amplify Your Voice: Mastering Political Expression in a Diverse World

You may want to see also

Ethical Concerns: Discuss conflicts of interest and potential corruption in revolving door practices

Revolving door politics, where individuals move between roles in government and private sectors, inherently blurs the lines between public service and personal gain. This fluidity raises ethical concerns, particularly regarding conflicts of interest and the potential for corruption. When a former regulator joins a company they once oversaw, or a corporate executive takes a government position, the risk of biased decision-making becomes palpable. Such transitions can undermine public trust, as citizens question whether policies are crafted for the common good or to benefit specific industries.

Consider the pharmaceutical industry, where former government health officials often transition to lucrative roles in drug companies. These individuals may possess insider knowledge of regulatory processes, granting their new employers an unfair advantage. For instance, a former FDA official might influence drug approval timelines or lobby for lenient regulations, directly benefiting their corporate employer. This scenario illustrates how revolving door practices can distort the regulatory landscape, prioritizing profit over public health. To mitigate this, stricter cooling-off periods—say, a mandatory two-year hiatus before transitioning sectors—could be enforced, ensuring decisions are made without immediate personal incentives.

Another critical issue is the normalization of lobbying by former public servants. Armed with access to current policymakers and intimate knowledge of government operations, these individuals can wield disproportionate influence. For example, a former congressional staffer turned lobbyist might draft legislation favorable to their client, effectively privatizing the legislative process. This not only skews policy outcomes but also creates a pay-to-play environment where wealth, not merit, dictates political access. Implementing transparent disclosure requirements and limiting lobbying activities for ex-officials could curb such abuses, restoring integrity to the political system.

The ethical dilemmas of revolving door politics extend beyond individual actions to systemic corruption. When the exchange of roles becomes routine, it fosters a culture where public service is seen as a stepping stone to private wealth. This erodes the principle of impartial governance, as officials may prioritize future career prospects over their current duties. For instance, a treasury official might soften financial regulations, anticipating a high-paying job at a bank post-government. Such behavior not only harms public interest but also perpetuates a cycle of influence-peddling. Addressing this requires comprehensive reforms, including stricter ethics guidelines and penalties for violations, to reinforce the boundary between public and private spheres.

Ultimately, the ethical concerns surrounding revolving door practices demand proactive solutions. While the exchange of expertise between sectors can be beneficial, it must be regulated to prevent exploitation. Policymakers should focus on creating frameworks that balance collaboration with accountability, ensuring that public service remains a noble endeavor, not a gateway to personal enrichment. By addressing conflicts of interest and potential corruption head-on, societies can rebuild trust in their institutions and safeguard the integrity of governance.

Stop Political Robocalls: Effective Strategies to Regain Your Peace

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Regulations: Explore laws and policies aimed at mitigating revolving door politics

Revolving door politics, where individuals move between roles as government officials and private sector lobbyists or executives, raises concerns about conflicts of interest and undue influence. To address these issues, several countries have implemented laws and policies aimed at mitigating this practice. These regulations vary widely in scope and effectiveness, but they share a common goal: to maintain public trust and ensure that government decisions serve the public interest rather than private gain.

One common approach is the imposition of cooling-off periods, which restrict former public officials from lobbying or working in industries they previously regulated for a specified time. For instance, the European Union mandates an 18-month cooling-off period for Commissioners, while the United States enforces a one-year ban on lobbying for former executive branch officials. These periods aim to reduce the immediate influence of private interests and allow for a clearer separation between public service and private employment. However, critics argue that such periods can be circumvented through indirect lobbying or by delaying career transitions, highlighting the need for stricter enforcement mechanisms.

Another strategy involves disclosure requirements, which mandate that former officials reveal their previous government roles and potential conflicts of interest when transitioning to the private sector. In Canada, the *Lobbying Act* requires lobbyists to register and disclose their activities, including any prior government affiliations. Similarly, the U.S. *STOCK Act* mandates public reporting of financial transactions by members of Congress and executive branch officials. While transparency is a step in the right direction, it relies on public scrutiny and media oversight to hold individuals accountable, which may not always be sufficient to prevent unethical behavior.

Ethics training and oversight bodies also play a crucial role in mitigating revolving door politics. Countries like France and Germany have established independent ethics committees to monitor and advise public officials on potential conflicts of interest. These bodies often provide guidelines on post-employment restrictions and conduct investigations into alleged violations. For example, France’s *Haute Autorité pour la Transparence de la Vie Publique* reviews the financial declarations of public officials and imposes penalties for non-compliance. Such institutions can strengthen accountability, but their effectiveness depends on their independence and the resources allocated to them.

Finally, some jurisdictions have explored stricter penalties for violations of revolving door regulations. In Australia, the *Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act* imposes fines and even criminal charges for breaches of post-separation employment rules. Similarly, South Korea has introduced legislation that not only bans former officials from lobbying but also penalizes companies that hire them in violation of the law. These measures send a strong deterrent message, but they must be balanced with the need to attract qualified individuals to public service without unduly restricting their future career options.

In conclusion, while no single regulation can entirely eliminate revolving door politics, a combination of cooling-off periods, disclosure requirements, ethics oversight, and penalties can significantly reduce its prevalence. Policymakers must continually evaluate and adapt these measures to address emerging challenges and ensure that public institutions remain free from undue private influence.

Exploring Teen Interest in Politics: Trends and Insights Revealed

You may want to see also

Impact: Analyze how revolving door politics affects governance, policy-making, and public trust

Revolving door politics, where individuals frequently transition between roles in government and the private sector, creates a governance ecosystem that prioritizes insider knowledge over public interest. This dynamic often results in policies that favor corporate or industry agendas, as former regulators or lawmakers leverage their government experience to advocate for private clients. For instance, a study by the Project On Government Oversight found that 64% of departing senior congressional staffers took jobs as lobbyists within a year, directly influencing legislation they once helped craft. This blurs the lines between public service and private gain, undermining the integrity of governance structures.

Consider the policymaking process, where revolving door politics fosters a symbiotic relationship between government and industry. Policymakers may draft regulations with future employment opportunities in mind, softening rules to curry favor with potential employers. For example, the pharmaceutical industry frequently hires former FDA officials, raising questions about the rigor of drug approvals. This "regulatory capture" distorts policy outcomes, ensuring they align with corporate interests rather than public welfare. The result? Policies that are less effective, more costly, and increasingly disconnected from the needs of ordinary citizens.

Public trust erodes as revolving door politics becomes more visible. When citizens perceive that government decisions are influenced by personal career advancement rather than the common good, they grow cynical. A 2020 Pew Research Center survey revealed that 77% of Americans believe government is run for the benefit of the few, not the many—a sentiment fueled by high-profile cases of officials moving seamlessly between public office and lucrative private roles. This distrust deepens political polarization and reduces civic engagement, as voters feel their voices are drowned out by powerful insiders.

To mitigate these impacts, practical reforms are essential. Implementing stricter cooling-off periods—say, a two-year ban on lobbying for former government officials—can reduce conflicts of interest. Requiring greater transparency in employment transitions and strengthening ethics enforcement agencies would also help. For instance, Canada’s Lobbying Act mandates public disclosure of lobbying activities, setting a precedent for accountability. By addressing these structural flaws, societies can begin to restore faith in governance and ensure policies serve the public, not just the privileged few.

A-Political Band Live: Music Beyond Borders and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Revolving door politics refers to the movement of individuals between roles as legislators, regulators, or government officials and positions in industries or lobbying firms that are affected by government decisions. This practice raises concerns about conflicts of interest and undue influence.

It is controversial because it can lead to policymakers prioritizing the interests of their future employers (e.g., corporations or lobbying groups) over the public good, creating a perception of corruption or favoritism.

It can influence policy-making by allowing industry insiders to shape regulations in their favor, potentially weakening oversight and benefiting private interests at the expense of public welfare.

Yes, many countries have implemented cooling-off periods, which restrict former government officials from lobbying or working in related industries for a certain period after leaving public office. However, enforcement varies widely.

Proponents argue that it can bring valuable expertise and insights from the private sector into government, fostering more informed and practical policy decisions. However, critics emphasize the risks of undue influence and ethical concerns.