Polyarchy, a term coined by political scientists Robert Dahl and Charles Lindblom, refers to a form of governance characterized by a pluralistic political system where power is distributed among multiple, competing groups and institutions. Unlike a single-party or authoritarian regime, polyarchy emphasizes the presence of free and fair elections, inclusive participation, and the protection of civil liberties, allowing diverse interests to influence decision-making. This model, often associated with democratic ideals, seeks to balance competition and cooperation among various political actors, ensuring that no single group dominates the political process. While polyarchy is widely regarded as a more equitable and stable form of governance, critics argue that it can perpetuate inequalities and be influenced by elite interests, raising questions about its effectiveness in achieving true political representation and equality.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Free and Fair Elections | Regular, competitive elections with universal suffrage, secret ballots, and minimal voter suppression. |

| Competing Political Parties | Existence of multiple, independent political parties with distinct ideologies and platforms, able to compete for power. |

| Active Civil Society | Robust network of independent organizations (NGOs, unions, etc.) that advocate for diverse interests and hold government accountable. |

| Rule of Law | Equal application of laws to all citizens, including government officials, with an independent judiciary to ensure fairness. |

| Human Rights Protections | Guarantees of fundamental freedoms like speech, assembly, religion, and due process, enshrined in law and upheld in practice. |

| Accountable Government | Transparency in decision-making, mechanisms for citizen participation, and institutions to hold leaders accountable for their actions. |

| Pluralistic Media | Diverse and independent media outlets providing a range of perspectives, free from government censorship or control. |

| Limited State Power | Checks and balances on government authority, preventing concentration of power and protecting individual liberties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Coined by Robert Dahl, polyarchy means rule by many, emphasizing competition and participation

- Key Characteristics: Free elections, inclusive citizenship, freedom of expression, and diverse political parties

- Polyarchy vs. Democracy: Polyarchy focuses on procedural fairness, while democracy emphasizes substantive equality

- Critiques of Polyarchy: Accused of being elitist, maintaining power structures, and limiting true citizen control

- Global Examples: Nations like Norway, Sweden, and Canada are often cited as polyarchic systems

Definition and Origins: Coined by Robert Dahl, polyarchy means rule by many, emphasizing competition and participation

Polyarchy, a term coined by political scientist Robert Dahl, challenges the simplistic notion of democracy as mere majority rule. It introduces a nuanced understanding of democratic governance, emphasizing not just the act of voting but the intricate interplay of competition and participation. Dahl’s concept goes beyond the ballot box, arguing that true democracy thrives when multiple power centers exist, fostering a dynamic environment where diverse voices can compete and citizens actively engage in the political process.

Imagine a marketplace of ideas, not goods. In a polyarchy, political parties, interest groups, and individuals vie for influence, not through coercion but through persuasion and the presentation of competing visions. This competition, Dahl argues, is essential for preventing the concentration of power and ensuring that governments remain responsive to the diverse needs and desires of their citizens.

Dahl’s inspiration for polyarchy stemmed from his observation of real-world democracies, which often fell short of the idealized model of direct citizen participation. He recognized that modern societies are too complex for every individual to be directly involved in every decision. Polyarchy, therefore, proposes a system where citizens participate not only through voting but also by joining associations, engaging in public discourse, and holding their representatives accountable. This multi-faceted participation strengthens the democratic fabric, making it more resilient to authoritarian tendencies and ensuring that power remains dispersed.

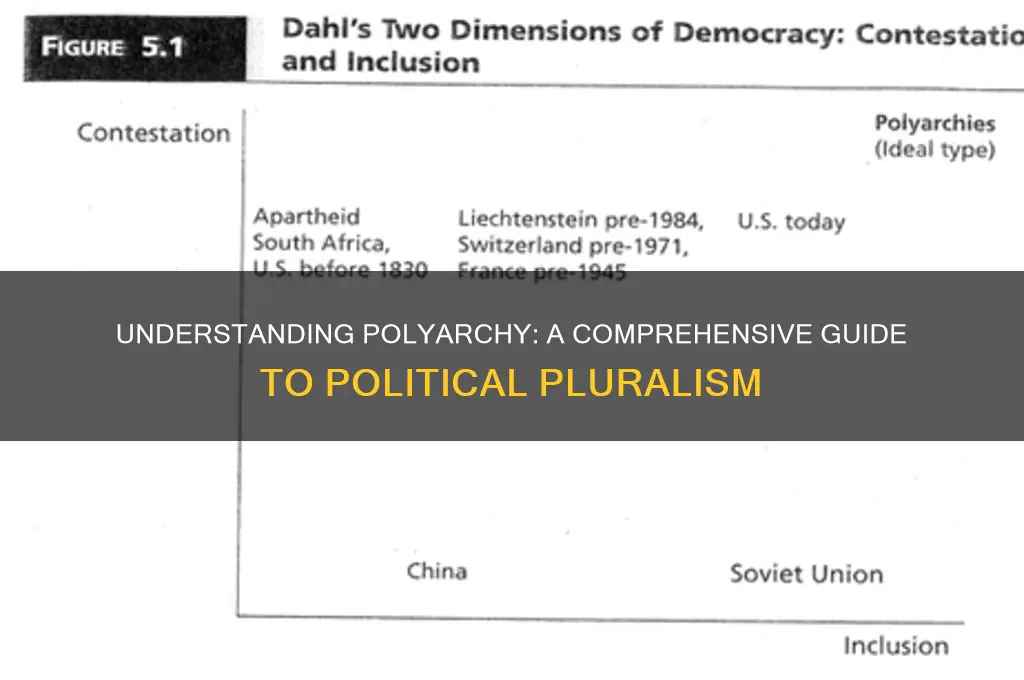

Understanding polyarchy requires moving beyond the binary of democracy versus dictatorship. It’s a spectrum, with polyarchy representing a high degree of democratic functioning characterized by open competition, widespread participation, and a vibrant civil society.

To cultivate polyarchy, societies must nurture an environment conducive to open debate, protect freedom of association, and ensure equal access to information. This involves strengthening institutions that facilitate participation, such as independent media, robust civil society organizations, and accessible legal systems. By embracing the principles of polyarchy, societies can move closer to the ideal of a truly democratic system where power is shared, voices are heard, and the rule of many prevails.

Corporate Influence in Politics: Shaping Policies and Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Key Characteristics: Free elections, inclusive citizenship, freedom of expression, and diverse political parties

Polyarchy, as a political concept, hinges on the interplay of four key characteristics: free elections, inclusive citizenship, freedom of expression, and diverse political parties. Each element is indispensable, yet their synergy defines the system’s robustness. Free elections, for instance, are not merely about casting votes but ensuring those votes are uncoerced, informed, and counted transparently. Without this foundation, the other pillars crumble. Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where allegations of fraud undermined public trust, illustrating how fragile this cornerstone can be.

Inclusive citizenship is the bedrock of polyarchy, ensuring all members of a society have equal rights to participate in political processes. This goes beyond legal equality to address systemic barriers like voter ID laws, literacy tests, or gerrymandering. For example, New Zealand’s Māori electorate seats guarantee indigenous representation, fostering inclusivity in practice. However, inclusivity is a moving target; as societies evolve, so must their definitions of citizenship. A 2022 study found that 23% of global democracies still disenfranchise certain groups, such as ex-felons or migrants, revealing gaps between theory and implementation.

Freedom of expression acts as polyarchy’s lifeblood, enabling citizens to critique, organize, and innovate without fear of retribution. This freedom is not absolute—it must be balanced against harms like hate speech—but its suppression signals democratic erosion. Take Hong Kong’s National Security Law, which curtailed dissent under the guise of stability, demonstrating how quickly this freedom can be eroded. Practical steps to protect it include strengthening independent media, decriminalizing defamation, and ensuring digital privacy. For activists, leveraging encrypted platforms and international advocacy networks can mitigate risks in repressive environments.

Diverse political parties are the engine of polyarchy, channeling varied interests into the political process. A two-party system, while efficient, risks marginalizing minority viewpoints, whereas multiparty systems encourage coalition-building and compromise. Germany’s Bundestag, with its proportional representation, exemplifies this diversity, though it can lead to fragmented governance. To foster diversity, democracies should lower barriers to party formation, such as reducing registration requirements or providing public funding for small parties. However, caution is needed: too many parties can lead to instability, as seen in Israel’s frequent elections.

In practice, these characteristics are interdependent. Free elections without inclusive citizenship become tools of exclusion; freedom of expression without diverse parties limits political alternatives. Policymakers must address these elements holistically, recognizing that polyarchy is not a static achievement but a dynamic process. For instance, Estonia’s e-voting system combines free elections with inclusive citizenship by ensuring accessibility for all, including the diaspora. Ultimately, polyarchy’s strength lies in its ability to adapt—to new technologies, demographic shifts, and global challenges—while preserving its core principles.

Understanding Political Office: Roles, Responsibilities, and Public Service Explained

You may want to see also

Polyarchy vs. Democracy: Polyarchy focuses on procedural fairness, while democracy emphasizes substantive equality

Polyarchy, as conceptualized by Robert Dahl, is a political system characterized by open competition among leaders, participation by citizens, and the existence of inclusive institutions. It prioritizes procedural fairness—ensuring that rules are applied consistently and transparently—over the outcomes those rules produce. Democracy, by contrast, is often understood as a system that seeks not just fair procedures but substantive equality, where the political process actively works to reduce disparities in power, wealth, and opportunity. This distinction highlights a fundamental tension: polyarchy guarantees the *how* of political participation, while democracy demands the *why*—equitable outcomes for all.

Consider the electoral process in a polyarchal system. Free and fair elections, a cornerstone of polyarchy, ensure that every vote is counted equally and that candidates compete on a level playing field. However, this procedural fairness does not address systemic barriers that prevent marginalized groups from fully participating or benefiting from the process. For instance, in a polyarchy, voter suppression tactics might be legally prohibited, but if they disproportionately affect minority communities, the system fails to achieve democratic ideals of substantive equality. Polyarchy’s focus on rules can inadvertently perpetuate inequality if those rules do not account for historical or structural disadvantages.

To illustrate, imagine a hypothetical nation where polyarchal principles are strictly enforced. Elections are held regularly, media is free, and opposition parties are allowed to campaign. Yet, if wealth inequality is extreme, wealthier candidates and parties will dominate the political landscape, skewing policies in their favor. In this scenario, procedural fairness exists, but substantive equality is absent. A democratic system, however, would seek to counteract this imbalance—through campaign finance reforms, wealth redistribution policies, or affirmative action—to ensure that political power reflects the diversity and needs of the population.

The challenge lies in balancing these two ideals. Polyarchy provides a stable framework for political competition, reducing the risk of authoritarianism by ensuring that power is contested. Democracy, however, pushes beyond this framework to address the root causes of inequality, often requiring interventionist policies that polyarchy might view as overreach. For example, a polyarchal system might reject affirmative action as a violation of meritocratic principles, while a democratic system would see it as necessary to correct historical injustices. This trade-off underscores the tension between maintaining fairness in process versus fairness in outcome.

In practice, achieving both procedural fairness and substantive equality requires deliberate design. Policymakers in polyarchal systems can adopt democratic principles by implementing measures like proportional representation, public funding for campaigns, and targeted social programs. Conversely, democratic systems must guard against the erosion of procedural fairness, ensuring that efforts to promote equality do not undermine the integrity of institutions. Ultimately, the goal is not to choose between polyarchy and democracy but to integrate their strengths—creating a system where fair procedures lead to equitable outcomes, and where equality is both a means and an end.

Are Japanese Men Polite? Exploring Cultural Etiquette and Gender Norms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Critiques of Polyarchy: Accused of being elitist, maintaining power structures, and limiting true citizen control

Polyarchy, often hailed as a model of democratic governance, is not without its detractors. One of the most persistent critiques is its perceived elitism. In theory, polyarchy promotes competition among multiple political parties and interest groups, ensuring a balance of power. However, in practice, this system often favors those with financial resources, social influence, or institutional backing. Wealthy individuals and corporations can disproportionately shape political outcomes through campaign funding, lobbying, and media control, effectively sidelining the voices of ordinary citizens. This raises questions about whether polyarchy truly serves the many or merely perpetuates rule by the few under the guise of democracy.

Another critique centers on polyarchy’s tendency to maintain existing power structures. By design, polyarchy emphasizes stability and incremental change, often at the expense of radical transformation. Established political parties and elites have a vested interest in preserving the status quo, which can stifle progressive reforms or systemic overhauls. For instance, in countries with deep-rooted inequalities, polyarchy may fail to address structural issues like racial injustice, economic disparity, or environmental degradation, as these require bold, disruptive action rather than the cautious compromises polyarchy encourages.

A third point of contention is the limited scope of citizen control within polyarchy. While citizens are granted the right to vote and participate in elections, their influence often ends there. Decision-making power remains concentrated in the hands of elected representatives, who may not always align with the will of the people. Referendums and direct democracy mechanisms are rarely utilized, leaving citizens with little recourse to challenge policies they oppose. This gap between electoral participation and meaningful control undermines the ideal of a truly participatory democracy.

To illustrate, consider the case of lobbying in polyarchic systems. In the United States, for example, corporate lobbying has led to policies favoring big business over public interest, such as tax breaks for corporations or weakened environmental regulations. Similarly, in India, political dynasties and wealthy elites dominate the political landscape, limiting opportunities for grassroots movements to gain traction. These examples highlight how polyarchy can become a tool for entrenching power rather than distributing it.

In conclusion, while polyarchy offers a framework for democratic governance, its elitist tendencies, preservation of power structures, and limited citizen control warrant critical examination. Advocates for more inclusive and equitable systems must address these shortcomings, exploring alternatives like participatory budgeting, decentralized governance, or stronger anti-corruption measures. Without such reforms, polyarchy risks becoming a hollow democracy, where the appearance of choice masks the reality of concentrated power.

Nonvoters and Political Awareness: Uninformed or Disengaged Citizens?

You may want to see also

Global Examples: Nations like Norway, Sweden, and Canada are often cited as polyarchic systems

Polyarchy, as a political concept, refers to a system where power is distributed among multiple, competing elites rather than being concentrated in a single group. This model is often associated with democratic stability, citizen participation, and the presence of robust institutions. Nations like Norway, Sweden, and Canada are frequently held up as exemplars of polyarchic systems, each embodying distinct features that contribute to their classification. These countries showcase how polyarchy can manifest in practice, offering valuable insights into its implementation and outcomes.

Consider Norway, a nation consistently ranked among the most democratic in the world. Its polyarchic structure is evident in the interplay between its parliamentary system, strong civil society, and decentralized governance. For instance, Norway’s *Storting* (parliament) operates with a multi-party system, where no single party dominates, fostering coalition-building and compromise. Additionally, the country’s extensive welfare state ensures broad-based participation in economic and social decision-making, a key tenet of polyarchy. Practical takeaways include the importance of institutional design: Norway’s proportional representation system and high voter turnout (averaging 78% in recent elections) demonstrate how electoral mechanisms can amplify citizen engagement.

Sweden, another Nordic model, exemplifies polyarchy through its emphasis on transparency and inclusivity. The Swedish *Riksdag* operates with a free and vibrant press, ensuring accountability among elites. Moreover, Sweden’s strong labor unions and employer associations act as countervailing powers, balancing economic interests and preventing the concentration of power. A notable example is the *Saltsjöbaden Agreement* of 1938, which institutionalized cooperation between labor and capital, a practice still influential today. For policymakers, Sweden’s model suggests that fostering dialogue between competing interests can stabilize polyarchic systems.

Canada’s polyarchic system, while distinct from its Nordic counterparts, thrives on its federal structure and multicultural policies. The country’s parliamentary democracy is complemented by a strong emphasis on regional representation, as seen in its Senate and provincial governments. Canada’s multiculturalism policy, enshrined in law since 1988, ensures that diverse groups have a voice in political processes, a critical aspect of polyarchy. A practical tip for replicating this model is to institutionalize diversity: Canada’s *Charter of Rights and Freedoms* guarantees minority rights, providing a framework for inclusive governance.

Comparatively, these nations highlight the adaptability of polyarchy. While Norway and Sweden emphasize welfare and consensus, Canada focuses on federalism and multiculturalism. Despite their differences, all three share a commitment to institutional checks, citizen participation, and the dispersion of power. A cautionary note, however, is that polyarchy is not without challenges: even in these nations, issues like political apathy, economic inequality, and elite capture persist. Policymakers should thus focus on continuous reform to sustain polyarchic principles.

In conclusion, Norway, Sweden, and Canada offer concrete examples of polyarchy in action, each with unique mechanisms for distributing power and ensuring participation. By studying their models—whether Norway’s welfare-driven democracy, Sweden’s labor-capital balance, or Canada’s multicultural federalism—we gain actionable insights into building and maintaining polyarchic systems. The key takeaway is that polyarchy requires not just democratic institutions but also a culture of inclusivity, transparency, and accountability.

Understanding Political Journalism: Role, Impact, and Ethical Challenges Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Polyarchy is a form of governance where power is shared among multiple groups or entities, rather than being concentrated in a single authority. It emphasizes political pluralism, competition, and citizen participation in decision-making processes.

The term polyarchy was popularized by political scientist Robert Dahl in his 1971 book *Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition*. Dahl used it to describe a democratic system characterized by openness, competition, and citizen engagement.

Polyarchy is a specific type of democracy that focuses on the practical aspects of political participation, competition, and representation. While democracy is a broader concept, polyarchy emphasizes the mechanisms that ensure power is distributed and contested among various groups.

The key features of polyarchy include free and fair elections, freedom of expression and association, the right to run for public office, diverse sources of information, and institutions that ensure political competition and accountability.

No, polyarchy and oligarchy are opposite systems. Polyarchy promotes power-sharing and political pluralism, while oligarchy refers to a system where power is held by a small, often elite, group of individuals.