Political vulnerability refers to the susceptibility of individuals, groups, or governments to external pressures, challenges, or threats that can undermine their power, stability, or legitimacy. It arises from a combination of factors, including weak institutions, economic disparities, social divisions, external interference, or ineffective leadership. Vulnerable political systems often struggle to address crises, maintain public trust, or resist manipulation by internal or external actors. Understanding political vulnerability is crucial for identifying risks, implementing reforms, and fostering resilience in governance structures, ultimately ensuring long-term stability and democratic integrity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Susceptibility of a political system, leader, or institution to instability, pressure, or collapse. |

| Key Factors | Economic inequality, social unrest, weak governance, corruption, external interference. |

| Economic Indicators | High unemployment, inflation, poverty rates, income disparities. |

| Social Indicators | Ethnic/religious tensions, inequality, lack of social cohesion, protests. |

| Political Indicators | Weak rule of law, authoritarianism, lack of transparency, frequent leadership changes. |

| External Influences | Geopolitical conflicts, sanctions, foreign interventions, global economic shocks. |

| Technological Impact | Misinformation spread via social media, cyberattacks on infrastructure. |

| Environmental Factors | Climate change impacts, resource scarcity, natural disasters. |

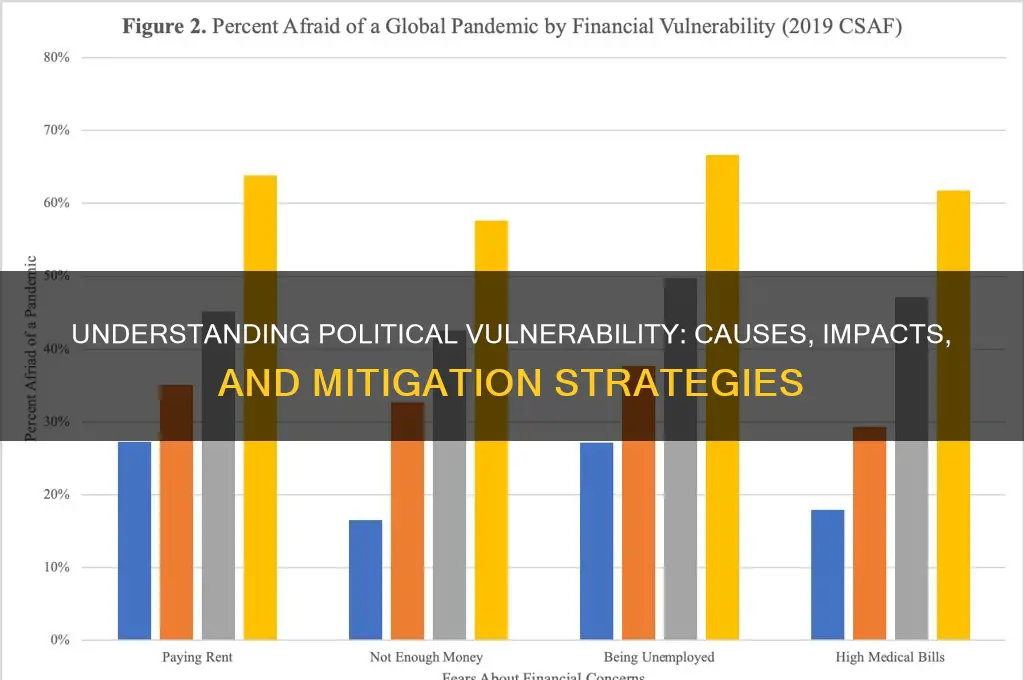

| Health Crises | Pandemics, inadequate healthcare systems, public health emergencies. |

| Global Trends | Rising populism, polarization, decline of democratic norms (e.g., Freedom House reports). |

| Mitigation Strategies | Strengthening institutions, inclusive policies, anti-corruption measures, public engagement. |

| Latest Data (2023) | Fragile States Index (FSI) 2023, Democracy Index, Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). |

Explore related products

$12.72 $19.99

What You'll Learn

- Economic Inequality: How wealth disparities create political vulnerability among marginalized communities

- Social Exclusion: Impact of discrimination and lack of representation on political vulnerability

- Institutional Weakness: Fragile governance structures amplifying political instability and vulnerability

- Environmental Risks: Climate change and resource scarcity as drivers of political vulnerability

- Media Influence: Role of misinformation and propaganda in exploiting political vulnerability

Economic Inequality: How wealth disparities create political vulnerability among marginalized communities

Wealth disparities are not merely economic issues; they are powerful catalysts for political vulnerability, particularly among marginalized communities. When a significant portion of a population struggles to meet basic needs while a small elite accumulates vast resources, the resulting inequality erodes the social contract. This imbalance fosters a sense of disenfranchisement, as those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder perceive the political system as rigged in favor of the wealthy. For instance, in the United States, the top 1% of households own nearly 30% of the country's wealth, while the bottom 50% hold just 2%. This stark divide translates into unequal political influence, as affluent individuals and corporations can outspend others in campaign contributions, lobbying efforts, and access to policymakers, effectively drowning out the voices of marginalized groups.

Consider the mechanics of this vulnerability: marginalized communities, often comprising racial and ethnic minorities, women, and low-income workers, face systemic barriers to economic mobility. These barriers include discriminatory hiring practices, lack of access to quality education, and predatory lending. As a result, these groups are disproportionately represented in low-wage jobs, with limited financial security and fewer resources to engage in political processes. For example, in many countries, voter turnout is significantly lower in impoverished neighborhoods due to logistical challenges, such as lack of transportation or inflexible work schedules. This underrepresentation in the political sphere perpetuates policies that favor the wealthy, creating a vicious cycle of economic and political marginalization.

To address this issue, policymakers and activists must adopt a multi-pronged approach. First, implement progressive taxation systems that redistribute wealth more equitably, ensuring that the wealthy contribute their fair share to public services and social safety nets. Second, invest in education and job training programs tailored to marginalized communities, breaking the cycle of poverty and empowering individuals to participate more fully in the economy and political life. Third, enact campaign finance reforms to reduce the influence of money in politics, such as public funding of elections and stricter limits on corporate donations. These steps, while challenging, are essential to dismantling the structural inequalities that fuel political vulnerability.

A comparative analysis of countries with varying levels of economic inequality reveals a clear pattern: nations with narrower wealth gaps, such as those in Scandinavia, tend to have more inclusive political systems. In these societies, robust welfare states and strong labor rights ensure that marginalized groups have the resources and opportunities to engage politically. Conversely, countries with high levels of inequality, like Brazil or South Africa, often experience social unrest and political instability, as excluded populations resort to protests or other forms of resistance to demand change. This comparison underscores the importance of addressing economic inequality not just as a moral imperative but as a strategy for fostering political stability and democratic resilience.

Finally, it is crucial to recognize that economic inequality does not operate in isolation; it intersects with other forms of marginalization, such as race, gender, and immigration status, to compound political vulnerability. For example, Black and Latino communities in the United States not only face higher rates of poverty but also experience disproportionate policing and voter suppression, further limiting their political agency. To combat this, advocacy efforts must adopt an intersectional lens, addressing the interconnected nature of these issues. By doing so, we can create more inclusive policies that not only reduce economic disparities but also amplify the voices of marginalized communities in the political arena.

Staten Island's Political Landscape: Conservative Stronghold in Liberal NYC

You may want to see also

Social Exclusion: Impact of discrimination and lack of representation on political vulnerability

Discrimination and lack of representation systematically exclude marginalized groups from political processes, amplifying their vulnerability. Consider the 2020 U.S. Census, which revealed that Black and Hispanic communities were undercounted by 3.3% and 4.9%, respectively. This data gap translates to reduced political representation, as census figures determine congressional seats and federal funding allocation. When these groups are invisible in the data, they become invisible in policy decisions, perpetuating cycles of poverty, inadequate healthcare, and limited access to education.

This exclusion manifests in tangible ways. For instance, gerrymandering often dilutes the voting power of minority communities by fragmenting their populations across districts. In North Carolina, a 2019 federal court ruled that Republican-drawn maps were unconstitutional for targeting African American voters, demonstrating how structural discrimination directly undermines political agency. Similarly, voter ID laws disproportionately affect low-income and minority voters, who are less likely to possess required identification. A 2014 study by the Government Accountability Office found that strict ID laws reduced turnout by 2-3 percentage points among these groups, effectively silencing their voices in elections.

The impact of this exclusion extends beyond elections. When marginalized groups lack representation in government, policies fail to address their unique needs. For example, Indigenous communities in Canada have long struggled with inadequate access to clean water. Despite comprising 5% of the population, they face 60% of all boil-water advisories nationwide. This crisis persists because Indigenous voices are underrepresented in decision-making bodies, leading to policies that prioritize other constituencies. Similarly, in the UK, the Windrush scandal highlighted how decades of systemic racism left Caribbean immigrants vulnerable to deportation, a direct result of their exclusion from political narratives and protections.

To mitigate this vulnerability, actionable steps are essential. First, implement proportional representation systems that ensure minority voices are reflected in legislative bodies. New Zealand’s Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system, for instance, has increased Māori representation in Parliament from 3% to 17% since its adoption in 1996. Second, mandate diversity training for policymakers to combat implicit biases that perpetuate exclusion. Third, strengthen anti-discrimination laws and enforce them rigorously, as seen in India’s Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, which provides legal recourse for marginalized communities. Finally, invest in civic education programs targeting excluded groups, empowering them to engage in political processes effectively.

The takeaway is clear: social exclusion through discrimination and lack of representation is not merely a social issue—it is a political crisis. By addressing these root causes, societies can reduce vulnerability, foster inclusivity, and build more equitable political systems. Without such measures, marginalized groups will remain trapped in a cycle of invisibility, their needs ignored and their potential untapped.

Is 'Hello All' Polite? Decoding Etiquette in Modern Greetings

You may want to see also

Institutional Weakness: Fragile governance structures amplifying political instability and vulnerability

Fragile governance structures often serve as the bedrock for political vulnerability, creating an environment where instability thrives. Consider the case of a country with a weak judiciary: when courts fail to enforce laws impartially, citizens lose faith in the system. This erosion of trust opens the door for corruption, as seen in nations like Venezuela, where judicial independence has been systematically undermined. The result? A political landscape ripe for manipulation, where powerful actors exploit weaknesses to consolidate control, leaving the populace vulnerable to authoritarian tendencies.

To address institutional weakness, it’s essential to identify its root causes. Weak governance often stems from inadequate checks and balances, poorly trained public servants, or outdated bureaucratic systems. For instance, in countries like South Sudan, the lack of a robust administrative framework has led to resource mismanagement and ethnic tensions. Strengthening institutions requires targeted interventions: invest in training programs for civil servants, modernize administrative processes, and establish independent oversight bodies. Without these steps, even well-intentioned policies will falter, amplifying political instability.

A comparative analysis reveals that nations with resilient institutions fare better during crises. Take the contrast between Italy and Germany during the Eurozone debt crisis. Italy’s fragmented political system struggled to implement reforms, while Germany’s stable governance structure allowed for swift, decisive action. The takeaway? Institutional resilience is not just about preventing vulnerability—it’s about building the capacity to respond effectively when challenges arise. Fragile governance, on the other hand, turns minor issues into major crises, leaving societies exposed to external and internal shocks.

Finally, a persuasive argument must be made for proactive institutional reform. Waiting for a crisis to expose weaknesses is a costly mistake. Governments must adopt a preventive approach: conduct regular audits of governance structures, engage citizens in transparency initiatives, and prioritize accountability. For example, Estonia’s e-governance model demonstrates how technology can strengthen institutions, reducing corruption and improving public trust. By acting now, nations can mitigate the amplifying effects of institutional weakness on political vulnerability, ensuring a more stable and secure future.

Understanding Political Conditions: Dynamics, Influences, and Societal Impacts Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Risks: Climate change and resource scarcity as drivers of political vulnerability

Climate change and resource scarcity are reshaping the political landscape, exposing nations to vulnerabilities that extend far beyond environmental degradation. Rising global temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and dwindling natural resources create a volatile mix that strains governance, fuels social unrest, and redefines geopolitical power dynamics. Consider the Syrian civil war, where a decade-long drought, exacerbated by climate change, displaced rural populations, intensified economic inequality, and contributed to the social fractures that ignited conflict. This example illustrates how environmental stressors can act as catalysts for political instability, particularly in regions with pre-existing social and economic tensions.

To understand the mechanics of this vulnerability, imagine a system where water scarcity, driven by prolonged drought, forces farmers to abandon their land. Urban migration ensues, overwhelming cities with jobless populations and straining infrastructure. Governments, already struggling with limited resources, face mounting pressure to provide relief, often failing to meet demands. This cycle of displacement, economic hardship, and governmental inadequacy breeds discontent, creating fertile ground for political opposition, extremism, or even state collapse. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, Lake Chad’s shrinking by 90% since the 1960s has displaced millions, exacerbating ethnic tensions and fueling the rise of groups like Boko Haram.

Mitigating these risks requires a multi-faceted approach. First, governments must invest in adaptive infrastructure, such as drought-resistant crops, water recycling systems, and renewable energy sources. For example, India’s push for solar energy not only reduces carbon emissions but also provides energy security in regions prone to coal shortages. Second, international cooperation is essential. Transboundary water agreements, like the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, demonstrate how shared resource management can prevent conflict. However, such agreements must be updated to reflect changing environmental realities.

A cautionary note: focusing solely on technological solutions or international treaties is insufficient. Addressing political vulnerability demands inclusive policies that prioritize equity. For instance, in the Arctic, melting ice has opened new shipping routes and resource extraction opportunities, but indigenous communities, whose livelihoods depend on stable ecosystems, are often excluded from decision-making processes. Their marginalization not only undermines social cohesion but also risks igniting resistance movements that challenge state authority.

Ultimately, the interplay between environmental risks and political vulnerability is a call to action. Nations must recognize that climate change and resource scarcity are not isolated issues but systemic threats that require proactive, integrated strategies. By combining adaptive measures, equitable policies, and global collaboration, societies can build resilience against the political upheavals that environmental degradation increasingly portends. The alternative—a world where ecological crises routinely destabilize governments—is a future no one can afford.

Understanding Political Transparency: Key Principles and Global Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Media Influence: Role of misinformation and propaganda in exploiting political vulnerability

Misinformation and propaganda thrive in the fertile soil of political vulnerability, exploiting uncertainties, divisions, and emotional triggers to shape public opinion. Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where targeted disinformation campaigns amplified existing societal fractures, swaying voter perceptions and outcomes. Such tactics aren’t confined to elections; they permeate policy debates, social movements, and even public health crises. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, false narratives about vaccines and treatments exploited public fear and distrust, undermining global health efforts. These examples illustrate how media-driven misinformation capitalizes on vulnerability, turning it into a weapon of influence.

To understand this dynamic, dissect the mechanics of misinformation. It often relies on emotional appeals rather than factual evidence, leveraging outrage, fear, or hope to bypass critical thinking. Propaganda, on the other hand, is more systematic, using repetition and authority figures to legitimize falsehoods. Both thrive in environments where political institutions are weak, trust is low, and citizens are polarized. Social media platforms exacerbate this by prioritizing engagement over accuracy, creating echo chambers where vulnerable audiences are repeatedly exposed to manipulated content. A 2021 study found that users aged 18–34 are twice as likely to share unverified information, highlighting the generational susceptibility to such tactics.

Combatting this requires a multi-pronged approach. First, media literacy education is essential. Teaching individuals to question sources, verify facts, and recognize manipulative techniques can build resilience against misinformation. For example, initiatives like Finland’s national media literacy program have shown measurable success in reducing susceptibility to false narratives. Second, platforms must take responsibility by implementing stricter content moderation policies and promoting credible sources. Third, policymakers need to enact legislation that holds both creators and disseminators of harmful misinformation accountable without infringing on free speech.

However, caution is necessary. Overzealous censorship can backfire, fueling conspiracy theories and deepening distrust. Striking a balance between regulation and freedom is critical. Additionally, fact-checking alone is insufficient; addressing the root causes of vulnerability—such as economic inequality, lack of transparency, and political polarization—is equally important. For instance, investing in public education and social welfare programs can reduce the desperation that makes individuals susceptible to manipulative narratives.

In conclusion, the role of media in exploiting political vulnerability through misinformation and propaganda is both profound and perilous. By understanding the mechanisms at play and implementing targeted solutions, societies can mitigate its impact. The challenge lies not just in correcting falsehoods but in fostering an environment where vulnerability is minimized, and informed decision-making becomes the norm. This is not merely a technical or educational issue but a fundamental question of democratic resilience in the digital age.

Mastering Political Conversations: Strategies for Intelligent and Respectful Dialogue

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political vulnerability refers to the susceptibility of a government, political leader, or system to criticism, opposition, or instability due to factors such as unpopular policies, scandals, economic crises, or public discontent.

Political vulnerability can be caused by poor governance, corruption, economic downturns, policy failures, public mistrust, external pressures, or a lack of responsiveness to citizens' needs.

Politically vulnerable leaders may face reduced public support, increased opposition, challenges within their own party, or even the risk of being removed from office through elections, impeachment, or other means.

Yes, political vulnerability can be managed through transparent governance, effective communication, responsive policies, addressing public concerns, and building strong alliances or coalitions.

Prolonged political vulnerability can lead to government instability, policy paralysis, erosion of public trust, social unrest, and potential regime change or systemic collapse.

![Austin Powers Triple Feature (International Man of Mystery / The Spy Who Shagged Me / Goldmember) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91YNHjASr0L._AC_UY218_.jpg)