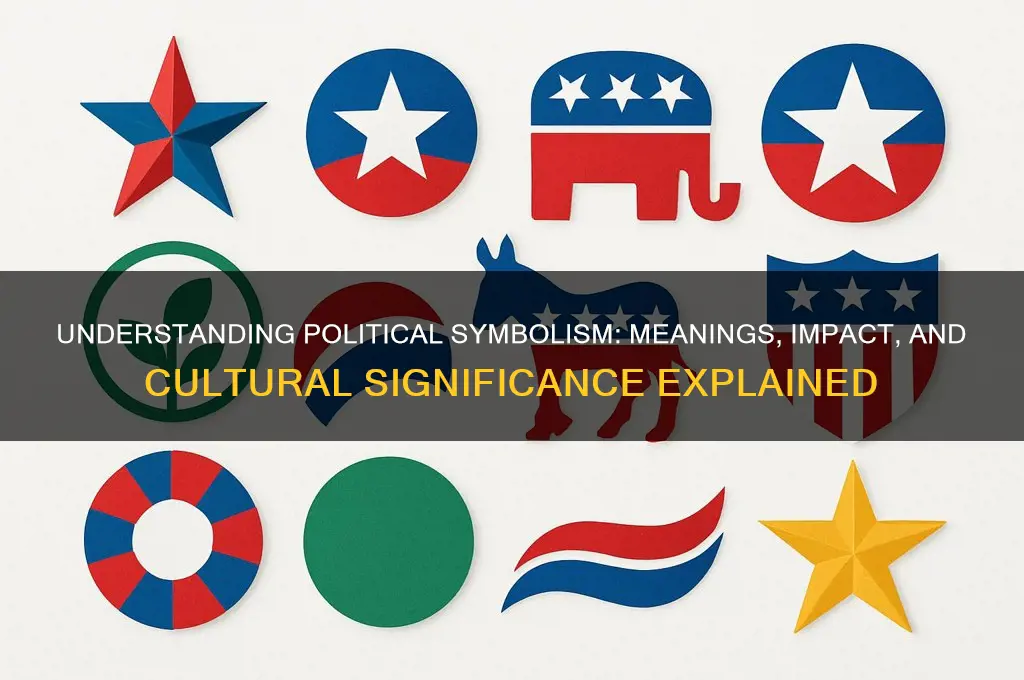

Political symbolism refers to the use of symbols, imagery, and representations to convey political ideas, ideologies, and identities. These symbols can range from flags and monuments to colors, gestures, and even clothing, often serving as powerful tools for communication, unity, and mobilization. By evoking emotions, reinforcing shared values, and distinguishing political groups or movements, symbolism plays a crucial role in shaping public perception and influencing political behavior. It transcends language barriers, making complex political concepts accessible and memorable, while also fostering a sense of belonging among supporters. Understanding political symbolism is essential for deciphering the underlying messages embedded in political discourse and visual culture.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The use of symbols, imagery, or representations to convey political ideas, ideologies, or identities. |

| Purpose | To communicate complex political messages, evoke emotions, or reinforce group identity. |

| Examples | Flags, national anthems, monuments, colors, slogans, and gestures. |

| Psychological Impact | Creates unity, fosters loyalty, or incites opposition through emotional resonance. |

| Cultural Significance | Rooted in shared history, traditions, or collective memory of a community. |

| Manipulation Potential | Can be used to manipulate public opinion, legitimize power, or marginalize groups. |

| Universal vs. Contextual | Some symbols (e.g., peace sign) are universal, while others (e.g., national flags) are context-specific. |

| Evolution Over Time | Symbols can change meaning or significance based on historical or political shifts. |

| Non-Verbal Communication | Often communicates political messages without explicit language. |

| Global vs. Local | Symbols can represent global movements (e.g., rainbow flag) or local identities (e.g., regional emblems). |

Explore related products

$11.19 $18.99

What You'll Learn

- Flags and National Identity: Symbols representing unity, history, and values of a nation

- Colors in Politics: Psychological and cultural meanings of colors used in political branding

- Monuments and Power: Statues and memorials as tools to shape collective memory and ideology

- Clothing as Statement: Political attire signaling affiliation, resistance, or authority in public discourse

- Rituals and Ceremonies: Formal events reinforcing political legitimacy and societal order

Flags and National Identity: Symbols representing unity, history, and values of a nation

Flags are among the most potent symbols of political identity, encapsulating a nation’s unity, history, and values in a single, often deceptively simple design. Consider the American flag: its 50 stars and 13 stripes represent the states and the original colonies, respectively, while the colors—red for valor, white for purity, and blue for justice—embed core national ideals. This combination of visual elements and symbolic meaning transforms a piece of fabric into a rallying point for collective identity, invoked in times of celebration, conflict, and mourning alike.

To design or interpret a flag effectively, focus on three key principles: simplicity, relevance, and distinctiveness. A flag should be recognizable at a distance, as demonstrated by the bold tricolor of France or the stark black, white, and red of Germany. Relevance ties the design to national history or geography, such as Japan’s Hinomaru (red circle on white), symbolizing the sun and the nation’s mythological origins. Distinctiveness ensures the flag stands apart from others, avoiding confusion—a lesson learned from the near-identical flags of Chad and Romania, which differ only in shade.

Flags also serve as tools for political persuasion, often co-opted to reinforce or challenge national narratives. During South Africa’s apartheid era, the flag was a divisive symbol of minority rule, but its redesign in 1994 incorporated colors from competing factions, signaling unity and reconciliation. Conversely, the Confederate flag in the U.S. remains a contentious emblem, representing heritage to some and oppression to others. These examples illustrate how flags can both unite and divide, depending on the context in which they are wielded.

Practical engagement with flags as symbols of identity can deepen civic understanding. Educators might encourage students to analyze their own nation’s flag, identifying historical references and values embedded in its design. Citizens can participate in flag-related traditions, such as proper display protocols or ceremonies, to foster a sense of shared responsibility. For instance, in the U.S., Flag Day (June 14) offers an opportunity to reflect on the flag’s meaning, while in India, the hoisting of the tricolor on Independence Day is a solemn yet celebratory act of patriotism.

Ultimately, flags are more than symbols—they are active participants in shaping national consciousness. Their power lies in their ability to condense complex histories and ideals into a visual language accessible to all. Whether flown atop government buildings, carried in protests, or worn as badges of honor, flags remind us of our collective past and shared aspirations. By understanding their design, history, and usage, we can better appreciate how these symbols continue to influence political identity and unity in an ever-changing world.

Is Partisanship a Political Label or a Divisive Force?

You may want to see also

Colors in Politics: Psychological and cultural meanings of colors used in political branding

Colors in politics are not arbitrary choices; they are deliberate tools wielding psychological and cultural power. Red, for instance, is a double-edged sword. In Western cultures, it evokes passion, urgency, and revolution, making it a staple for leftist movements like socialism and communism. Yet, in China, red symbolizes good fortune and joy, aligning with the Communist Party’s branding. This duality underscores how cultural context reshapes color meanings, demanding precision in political branding.

Consider blue, a color dominating centrist and conservative parties globally. Psychologically, blue conveys trust, stability, and calm—qualities parties like the U.S. Democrats or U.K. Conservatives leverage to appeal to broad electorates. However, in some Middle Eastern cultures, blue is associated with evil or sadness, illustrating how a universally "safe" color can misfire without localized research. Political strategists must balance global trends with regional sensitivities to avoid unintended interpretations.

Green’s association with nature and growth has made it the go-to color for environmental parties, such as Germany’s Green Party. Yet, its meaning shifts dramatically in other contexts: in Islam, green represents paradise, while in some Asian cultures, it’s linked to infidelity. For political branding, this requires strategic layering—pairing green with complementary colors or symbols to reinforce intended messages while mitigating cultural dissonance.

Yellow, often tied to optimism and energy, is a wildcard in political branding. Ukraine’s use of yellow in its flag symbolizes wheat fields and prosperity, while in Egypt, it was adopted during the 2011 protests to signify hope. However, in Latin America, yellow can denote cowardice. Parties adopting yellow must test its resonance through focus groups or surveys, ensuring it aligns with campaign narratives rather than undermining them.

Black and white, though not colors in the traditional sense, carry profound political weight. Black’s association with power and elegance has been co-opted by authoritarian regimes, while white’s purity resonates in peace movements. However, their starkness can polarize—black may appear aggressive, white too sterile. Political brands using these hues should temper them with accents or gradients to soften their impact while retaining symbolic strength.

Mastering color psychology in political branding requires a three-step approach: research cultural nuances, test audience perceptions, and adapt strategies accordingly. A misstep can alienate voters, but a well-executed palette becomes a silent ambassador, embedding party values into the public psyche. In the theater of politics, colors aren’t just seen—they’re felt, remembered, and voted on.

Understanding Political Runoffs: A Comprehensive Guide to How They Work

You may want to see also

Monuments and Power: Statues and memorials as tools to shape collective memory and ideology

Monuments and memorials are not neutral artifacts of history; they are deliberate constructs of power, designed to shape collective memory and reinforce ideological narratives. Consider the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. Erected in 1886, it was intended to symbolize freedom and democracy, aligning with America’s self-image as a beacon of hope. Yet, its meaning has been contested, with critics arguing it also reflects exclusionary immigration policies and Eurocentric values. This duality underscores how monuments serve as tools of political symbolism, embedding dominant ideologies into public consciousness while often obscuring counter-narratives.

To understand their impact, examine the process of monument creation. Governments and elites typically commission statues and memorials to commemorate specific events, figures, or values. For instance, the Soviet Union’s monumental statues of Lenin were not mere tributes but instruments to propagate communist ideology and consolidate state authority. Similarly, Confederate statues in the U.S. South were erected during the Jim Crow era to glorify a revisionist history of the Civil War and intimidate African Americans. These examples illustrate how monuments are strategically deployed to control the narrative of the past, thereby influencing present and future beliefs.

However, the power of monuments is not static; it can be challenged and redefined. The global movement to remove statues of colonialists and slave traders, such as the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol in 2020, demonstrates how public spaces can become battlegrounds for ideological struggle. Such acts force societies to confront uncomfortable truths and reconsider whose stories are told and whose are erased. This dynamic highlights the dual role of monuments: as both enforcers of power and catalysts for change.

Practical steps for engaging with monuments critically include researching their historical context, questioning their purpose, and advocating for inclusive public art. For educators, incorporating monument analysis into curricula can foster a deeper understanding of political symbolism. For activists, campaigns to rename, relocate, or reinterpret monuments can shift the cultural landscape. Ultimately, monuments are not just stone and metal—they are living dialogues between power, memory, and identity, demanding active participation in their interpretation and transformation.

Do Political Signs Influence Votes or Just Clutter Yards?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Clothing as Statement: Political attire signaling affiliation, resistance, or authority in public discourse

Clothing has long served as a silent yet powerful medium for political expression, transcending its utilitarian purpose to become a canvas for affiliation, resistance, and authority. From the suffragettes' white dresses to the Black Panthers' leather jackets, attire has been strategically deployed to communicate ideologies and challenge power structures. This phenomenon is not confined to historical movements; it persists in contemporary public discourse, where a single garment can spark conversations, provoke outrage, or solidify identities. Understanding the mechanics of political attire requires dissecting its intent, context, and reception, as well as its ability to amplify or subvert dominant narratives.

Consider the act of donning a red hat in the United States post-2016. The "Make America Great Again" cap, initially a campaign accessory, evolved into a symbol of political affiliation, instantly signaling the wearer's alignment with a specific ideology. Its impact lies not in its design but in its cultural encoding—a lesson in how clothing can condense complex political beliefs into a recognizable, wearable statement. Conversely, the hijab, often politicized in Western discourse, serves as both a religious garment and a symbol of resistance against cultural assimilation, demonstrating how attire can simultaneously assert identity and challenge external narratives. These examples underscore the dual role of clothing: as a tool for inclusion within a group and as a barrier against external pressures.

To effectively use clothing as a political statement, one must navigate its potential pitfalls. A misstep can reduce a powerful message to a caricature or provoke unintended backlash. For instance, the appropriation of symbols from marginalized communities by outsiders can dilute their significance and perpetuate harm. Practical tips include researching the historical and cultural context of a garment, ensuring alignment with the intended message, and considering the audience's interpretation. For instance, a Che Guevara t-shirt, while iconic, may be perceived as superficial if worn without understanding the revolutionary's legacy. Age and setting also matter; a protest sign on a t-shirt might be appropriate for a rally but out of place in a professional setting, where subtler cues like a lapel pin could convey the same message more tactfully.

Comparatively, political attire operates differently across cultures and regimes. In authoritarian states, a simple color or accessory can become a dangerous act of defiance, as seen in Iran's "White Wednesdays" movement against compulsory hijab laws. In democracies, the same act might be protected as free speech, highlighting the interplay between clothing and political freedom. This contrast reveals how the same garment can carry varying weights of risk and resistance depending on its context. For those seeking to engage in this form of expression, studying these global nuances can deepen the impact of their statement while fostering solidarity with movements beyond their own borders.

Ultimately, clothing as political symbolism is a dynamic, ever-evolving practice that demands intentionality and awareness. It is not merely about wearing a message but about understanding the dialogue it initiates. Whether signaling allegiance, challenging norms, or asserting authority, attire in public discourse is a testament to the human desire to communicate beyond words. By mastering its language—its history, its risks, and its potential—individuals can transform their wardrobe into a powerful instrument of political engagement.

Hamilton's Political Narrative: Unveiling the Musical's Civic Discourse

You may want to see also

Rituals and Ceremonies: Formal events reinforcing political legitimacy and societal order

Rituals and ceremonies serve as the backbone of political symbolism, embedding authority and order into the fabric of society through meticulously choreographed events. Consider the U.S. presidential inauguration, where the Oath of Office, the 21-gun salute, and the inaugural address are not mere traditions but calculated acts of legitimacy. Each element—from the timing (January 20 at noon) to the presence of past presidents—reinforces the continuity of governance. These rituals transform political power from abstract to tangible, making it relatable to citizens while asserting the state’s sovereignty.

To design an effective political ceremony, follow these steps: first, anchor the event in historical or cultural narratives to evoke shared identity. For instance, India’s Republic Day parade showcases military strength and cultural diversity, blending tradition with modernity. Second, incorporate symbolic objects or gestures, such as the raising of a flag or the lighting of a ceremonial torch, to create visual and emotional resonance. Third, ensure inclusivity by involving diverse societal groups, as seen in South Africa’s Freedom Day celebrations, which commemorate the end of apartheid. Caution: avoid excessive militarization or exclusionary practices, as these can alienate segments of the population and undermine the ceremony’s unifying purpose.

Analytically, the power of rituals lies in their ability to condense complex political ideologies into digestible, memorable forms. Take the annual Trooping the Colour in the U.K., a military spectacle celebrating the monarch’s birthday. While seemingly archaic, it reinforces the Crown’s symbolic role as a unifying force in a constitutional monarchy. Similarly, China’s National Day parade in Tiananmen Square displays military might and technological advancement, signaling both domestic stability and global ambition. These events are not just performances; they are strategic tools for shaping public perception and consolidating power.

A comparative lens reveals how rituals adapt to different political systems. In democracies, ceremonies often emphasize civic participation, as in France’s Bastille Day, which invites citizens to celebrate national identity through parades and fireworks. In contrast, authoritarian regimes may prioritize displays of strength and control, as seen in North Korea’s mass games, where synchronized performances glorify the state. Despite their differences, both approaches aim to foster obedience and loyalty, illustrating the universal utility of rituals in political governance.

Practically, organizers must balance tradition with relevance to ensure ceremonies remain impactful. For instance, updating ceremonial attire or incorporating digital elements can modernize rituals without sacrificing their core meaning. Additionally, engaging younger audiences through educational programs or social media campaigns can extend the ceremony’s reach. Takeaway: rituals and ceremonies are not static relics but dynamic instruments of political communication, requiring careful design and adaptation to fulfill their role in legitimizing authority and maintaining societal order.

Mastering Polite RN Delegation: Effective Communication Strategies for Nurses

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political symbolism refers to the use of symbols, such as flags, colors, gestures, or imagery, to represent political ideas, ideologies, or movements. These symbols often carry emotional and cultural significance, helping to communicate complex political messages in a simple and powerful way.

Political symbolism is important because it unifies people around shared values, strengthens collective identity, and mobilizes support for political causes. It can also evoke emotions, shape public opinion, and reinforce the legitimacy of governments or movements.

Yes, political symbolism can be manipulated or misused to propagate misinformation, incite division, or suppress dissent. Symbols can be co-opted by extremist groups or used to exclude certain communities, highlighting the need for critical awareness of their meaning and impact.