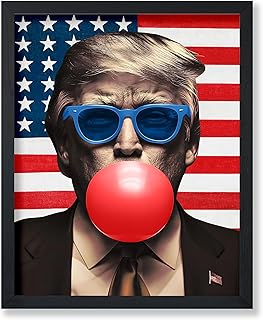

Political Pop Art is a dynamic and thought-provoking genre that merges the vibrant, accessible aesthetics of traditional pop art with sharp social and political commentary. Emerging as a response to the consumer-driven culture of the mid-20th century, it repurposes iconic imagery from mass media, advertising, and popular culture to critique power structures, inequality, and global issues. Artists in this movement often employ bold colors, recognizable symbols, and irony to engage viewers, making complex political themes more digestible while challenging societal norms. By blending entertainment with activism, Political Pop Art serves as both a mirror and a critique of contemporary society, inviting audiences to question the status quo and reimagine the world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Subject Matter | Focuses on political issues, social commentary, and current events. |

| Visual Style | Bold, vibrant, and often satirical, borrowing from pop culture and advertising. |

| Use of Icons | Incorporates political figures, symbols, and cultural icons. |

| Mass Media Influence | Draws inspiration from mass media, including newspapers, TV, and social media. |

| Irony and Satire | Employs irony, humor, and exaggeration to critique power structures. |

| Accessibility | Designed to be accessible to a broad audience, often using simple imagery. |

| Consumer Culture Critique | Often critiques consumerism and its intersection with politics. |

| Mixed Media | Combines traditional art techniques with modern materials like silkscreen and digital art. |

| Provocative Messaging | Aims to provoke thought, debate, and action on political topics. |

| Historical and Contemporary Relevance | Addresses both historical and contemporary political issues. |

| Global Perspective | Often reflects global political concerns, not limited to a single nation. |

| Intertextuality | References other artworks, media, and cultural texts to create layered meanings. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Influences: Emerged in the 1950s, blending pop culture with political commentary, inspired by mass media

- Key Artists: Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Hamilton used bold imagery to critique power and society

- Themes Explored: War, consumerism, and inequality are central, reflecting global political tensions

- Techniques Used: Employs satire, irony, and appropriation to challenge political narratives visually

- Modern Relevance: Continues to address contemporary issues like climate change and social justice

Origins and Influences: Emerged in the 1950s, blending pop culture with political commentary, inspired by mass media

Political pop art, emerging in the 1950s, was a bold response to the rapidly changing cultural and political landscape of the post-war era. This movement didn’t just mirror the times—it dissected them, blending the glossy allure of pop culture with sharp political critique. Artists like Richard Hamilton and Robert Rauschenberg pioneered this fusion, using everyday imagery from advertisements, comics, and television to challenge societal norms and question authority. Their work wasn’t merely decorative; it was a weapon of commentary, turning the familiar into a mirror reflecting the absurdities and injustices of the age.

The 1950s were a fertile ground for this movement, as mass media began to saturate Western societies. Television sets became household staples, and magazines flooded homes with images of consumerism and idealized lifestyles. Political pop artists seized these tools, repurposing them to expose the contradictions beneath the surface. For instance, Hamilton’s *Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?* (1956) juxtaposed muscular bodies, household gadgets, and pop culture icons to satirize the consumerist dream. This wasn’t just art—it was a visual manifesto, dismantling the era’s materialistic ethos.

Mass media wasn’t just an inspiration; it was the raw material of political pop art. Artists scavenged images from newspapers, billboards, and product packaging, recontextualizing them to provoke thought. Andy Warhol’s *Campbell’s Soup Cans* (1962) is a prime example. On the surface, it’s a mundane product, but Warhol’s repetition elevated it to a critique of mass production and cultural homogenization. This technique—taking the ordinary and making it extraordinary—became a hallmark of the movement, forcing viewers to question the meaning behind the images they encountered daily.

The political edge of this art was sharpened by the turbulent events of the time. The Cold War, civil rights struggles, and the Vietnam War provided ample fodder for critique. Artists like Faith Ringgold and Eduardo Paolozzi didn’t shy away from controversy; they embraced it. Ringgold’s *The American People Series #20: Die* (1967) tackled racial violence with unflinching honesty, while Paolozzi’s collages spliced political figures with dystopian imagery. These works weren’t passive observations—they were calls to action, urging viewers to engage with the issues shaping their world.

What sets political pop art apart is its accessibility. Unlike abstract or elitist art forms, it spoke directly to the masses, using their own cultural language. This democratization of art made it a powerful tool for social change. Practical tip: To understand its impact, try this exercise—collect images from today’s media (social media posts, ads, news headlines) and rearrange them to tell a different story. You’ll quickly see how political pop art’s methods remain relevant, offering a blueprint for modern critique. Its legacy isn’t just in museums; it’s in every meme, protest poster, and viral image that challenges the status quo.

Congress Recap: Key Votes, Debates, and Decisions from Yesterday's Session

You may want to see also

Key Artists: Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Hamilton used bold imagery to critique power and society

Political Pop Art emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as a bold response to the consumerism, media saturation, and political tensions of the era. At its core, it repurposed the imagery of popular culture to challenge power structures and societal norms. Three artists stand out for their masterful use of bold imagery to critique authority and culture: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Richard Hamilton. Each brought a unique approach, but all shared a commitment to exposing the contradictions and absurdities of their time.

Consider Warhol’s *Marilyn Diptych* (1962), a grid of 50 images of Marilyn Monroe, half in vibrant color and half fading to monochrome. This piece isn’t just a tribute to a Hollywood icon; it’s a commentary on the commodification of fame and the fleeting nature of identity in a media-driven society. Warhol’s repetitive, almost mechanical style mirrors the mass production of celebrity, forcing viewers to confront how power structures exploit individuality. To engage with this work, observe how the fading images evoke the fragility of Monroe’s life, juxtaposed against her immortalized public persona. This duality is a practical lens for analyzing how media constructs and deconstructs power.

Lichtenstein, on the other hand, borrowed from comic strips to critique the superficiality of American culture and its militaristic tendencies. His *Whaam!* (1963) depicts a fighter jet firing a missile, rendered in the bold lines and primary colors of a comic book. The irony lies in how he elevates a trivial medium to fine art while simultaneously mocking the glorification of war. Lichtenstein’s use of Ben-Day dots—a printing technique—exposes the artificiality of both media and military narratives. To deepen your understanding, compare *Whaam!* to actual wartime propaganda. Notice how Lichtenstein’s detachment and humor dismantle the heroic veneer of power, offering a cautionary tale about the dangers of uncritical acceptance.

Hamilton’s *Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?* (1956) is a collage of consumer goods, muscular bodies, and pop culture icons, creating a chaotic yet pointed critique of post-war affluence. This work serves as a blueprint for decoding the symbols of power in everyday life. Hamilton’s juxtaposition of a bodybuilder couple surrounded by vacuums, TVs, and canned food highlights the absurdity of equating material wealth with happiness. To apply this critique, audit your own environment: identify the products and images that subtly reinforce societal expectations. Hamilton’s piece reminds us that power isn’t just in institutions but in the mundane choices we’re conditioned to make.

Together, Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Hamilton demonstrate how bold imagery can serve as both a mirror and a hammer. Their works aren’t just reflections of their time but tools for dismantling the ideologies that shape society. By studying their techniques—repetition, irony, and juxtaposition—we can develop a sharper eye for the hidden messages in our own media landscape. The takeaway? Political Pop Art isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s a call to question, resist, and reimagine the power structures that govern our lives.

Language, Power, and Politics: Unveiling the Hidden Ideologies in Words

You may want to see also

Themes Explored: War, consumerism, and inequality are central, reflecting global political tensions

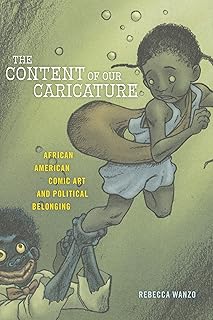

Political pop art, with its vibrant colors and bold imagery, often serves as a mirror to society’s most pressing issues. Among its central themes, war emerges as a recurring motif, reflecting the global anxieties of conflict and its human toll. Artists like Peter Saul and Martha Rosler have used this genre to critique militarism and the absurdity of warfare, blending cartoonish aesthetics with stark, unsettling messages. Saul’s *Vietnam* series, for instance, juxtaposes the horrors of war with the banal familiarity of pop culture, forcing viewers to confront the disconnect between media representation and lived reality. This approach doesn’t just document war—it challenges the viewer to question their complicity in a culture that normalizes violence.

Consumerism, another cornerstone of political pop art, is dissected through the lens of excess and exploitation. Artists like James Rosenquist and Pauline Boty expose the seductive yet hollow promises of capitalism, often by appropriating advertising imagery and subverting its intent. Rosenquist’s *F-111*, a 23-panel mural, merges images of consumer goods with military machinery, highlighting the symbiotic relationship between corporate profit and war. This critique isn’t merely observational; it’s instructional. By deconstructing the visual language of ads, these artists teach viewers to recognize how consumerism shapes desires and distracts from systemic issues. Practical tip: Next time you see an ad, ask yourself, *What is this really selling?*

Inequality, the third pillar, is explored through works that amplify marginalized voices and expose power imbalances. Artists like Faith Ringgold and Keith Haring use pop art’s accessibility to address racial, economic, and social disparities. Ringgold’s *The American People Series #20: Die*, for example, confronts racial violence with a stark, unflinching gaze, while Haring’s iconic figures advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and AIDS awareness. These pieces aren’t just art—they’re calls to action. To engage with this theme, consider curating a playlist or reading list that pairs political pop art with contemporary activism, creating a dialogue across mediums.

Comparatively, while war, consumerism, and inequality are distinct themes, they intersect in political pop art to form a cohesive critique of global political tensions. War fuels consumerism through military-industrial complexes, consumerism perpetuates inequality by prioritizing profit over people, and inequality often leads to the conflicts that define war. This cyclical relationship is best understood through a comparative lens. For instance, juxtapose Boty’s *It’s a Man’s World I* with Haring’s *Untitled (Against All Odds)* to see how gender and economic inequality are portrayed across different contexts. Takeaway: Political pop art isn’t just about individual themes—it’s about their interconnectedness and the systems they expose.

Finally, the persuasive power of political pop art lies in its ability to make the political personal. By blending the familiar with the confrontational, it invites viewers to see themselves as both participants in and victims of these global tensions. For educators or activists, incorporating political pop art into discussions can make abstract concepts tangible. Start with a guided analysis of a single piece, like Barbara Kruger’s *Your Body is a Battleground*, then expand to group discussions on how its message applies to local or global issues. Caution: Avoid oversimplifying the art’s message—its strength lies in its complexity. Conclusion: Political pop art doesn’t just reflect global tensions; it equips us to question and challenge them.

Hacking's Political Evolution: Cyber Warfare and Global Power Struggles

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Techniques Used: Employs satire, irony, and appropriation to challenge political narratives visually

Political pop art wields satire as a sharp tool to dissect power structures, often exaggerating flaws in political figures or systems to provoke thought. Consider Banksy’s *Girl with Balloon*, where a child reaches for a heart-shaped balloon against a bleak, graffitied wall. The simplicity of the image contrasts with its critique of hope’s fragility in a chaotic world, forcing viewers to question societal priorities. Satire here isn’t just humor—it’s a mirror held up to reality, distorting it just enough to reveal uncomfortable truths. To employ this technique effectively, artists must balance exaggeration with recognizability, ensuring the critique lands without alienating the audience.

Irony in political pop art thrives on the gap between expectation and reality, often using familiar symbols to subvert their intended meaning. Shepard Fairey’s *Obey Giant* campaign, for instance, co-opts the authoritarian undertones of propaganda posters but redirects them toward questioning blind obedience. The irony lies in the viewer’s recognition of the style’s historical roots, paired with its modern, rebellious message. Artists using irony must carefully layer meaning, ensuring the work resonates on both surface and deeper levels. A practical tip: pair ironic imagery with neutral or contradictory text to amplify the tension between form and content.

Appropriation—the act of borrowing and recontextualizing existing images—is a cornerstone of political pop art, challenging ownership and authority. Barbara Kruger’s use of mass media visuals overlaid with bold, declarative text (e.g., *I Shop Therefore I Am*) reclaims commercial imagery to critique consumerism and identity. When appropriating, artists should consider legal and ethical boundaries, ensuring the act of borrowing serves a transformative purpose. A caution: over-reliance on recognizable imagery can dilute the message, so pair appropriation with original elements to maintain freshness.

Combining these techniques—satire, irony, and appropriation—creates a visual language that disrupts passive consumption of political narratives. For example, Keith Haring’s *Crack is Wack* mural appropriates public space, uses irony to confront the war on drugs’ failures, and employs satire to highlight systemic neglect. To replicate this approach, start by identifying a political issue, then select a widely recognized image or symbol to appropriate. Layer irony through unexpected juxtaposition, and sharpen the critique with satirical exaggeration. The takeaway: these techniques aren’t just stylistic choices—they’re strategic tools to engage, provoke, and empower viewers to question the status quo.

Discovering Your Political Alignment: A Guide to Understanding Your Beliefs

You may want to see also

Modern Relevance: Continues to address contemporary issues like climate change and social justice

Political pop art, born in the 1950s as a critique of consumerism and mass media, has evolved to mirror the pulse of contemporary struggles. Today, it serves as a vibrant, accessible medium for addressing urgent global issues like climate change and social justice. Artists repurpose the movement’s signature bold colors, iconic imagery, and irony to amplify messages that resonate across digital and physical spaces. This modern iteration isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s a call to action, leveraging familiarity to provoke thought and inspire change.

Consider the work of artists like Shepard Fairey, whose "Earth Crisis" series merges pop art’s graphic style with stark environmental warnings. These pieces don’t just decorate walls—they demand attention, using recognizable symbols like melting ice caps or endangered species to confront viewers with the reality of ecological collapse. Similarly, social justice themes are tackled through reimagined corporate logos or satirical portrayals of political figures, exposing systemic inequalities with a dose of dark humor. Such works act as visual protests, translating complex issues into digestible, shareable formats ideal for social media amplification.

To create effective political pop art addressing these issues, follow these steps: 1) Identify a specific issue (e.g., plastic pollution or racial injustice) and research its key symbols and narratives. 2) Appropriate iconic imagery from popular culture—think fast-food logos drowning in oil spills or superhero figures marching in protests. 3) Layer irony or contrast to highlight contradictions, such as a smiley face wearing a gas mask. 4) Use bold, high-contrast colors to ensure the message cuts through the noise. 5) Distribute widely, leveraging Instagram, murals, or prints to reach diverse audiences. Caution: Avoid oversimplification; balance accessibility with depth to avoid trivializing serious topics.

The power of this art lies in its ability to bridge the gap between activism and everyday life. Unlike traditional political art, which can feel exclusive or abstract, pop art’s familiarity invites engagement. For instance, a poster blending the Coca-Cola logo with images of drought-stricken farms doesn’t just criticize corporate water usage—it challenges consumers to reconsider their choices. This dual role as both mirror and megaphone makes it uniquely suited to modern advocacy, where capturing attention is half the battle.

Ultimately, the modern relevance of political pop art is its adaptability. As issues evolve—from the civil rights movement to the climate crisis—so does its vocabulary. It’s not just art for art’s sake; it’s a tool for democratizing discourse, making activism approachable without sacrificing impact. In a world overwhelmed by information, these vibrant, provocative works serve as beacons, reminding us that art isn’t just a reflection of society—it’s a force shaping it.

Decoding Political Language: Understanding Its Power, Purpose, and Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political pop art is a genre that combines elements of pop art with political commentary, using bold imagery, vibrant colors, and popular culture references to critique social, economic, or political issues.

Notable artists include Banksy, Keith Haring, Barbara Kruger, and Shepard Fairey, who use their work to address themes like power, inequality, and activism.

While traditional pop art often focuses on consumer culture and mass media, political pop art explicitly incorporates messages of dissent, resistance, or critique of societal structures.

Artists frequently use screen printing, collage, stencils, and appropriation of iconic images to create impactful and thought-provoking pieces.

It serves as a powerful tool for raising awareness, sparking dialogue, and challenging the status quo, making complex political issues accessible to a broader audience.