Political parties and pressure groups are fundamental components of modern democratic systems, each playing distinct yet interconnected roles in shaping public policy and governance. Political parties are organized groups that contest elections, seek to gain political power, and implement their ideologies and agendas once in office. They serve as intermediaries between the state and the citizens, aggregating interests and providing a structured platform for political participation. In contrast, pressure groups, also known as interest groups, are organizations that advocate for specific causes or interests without directly seeking political office. They operate by influencing policymakers, mobilizing public opinion, and lobbying for changes in legislation or government actions. While political parties focus on winning elections and governing, pressure groups concentrate on advocating for particular issues, often representing narrower or specialized interests. Together, they contribute to the pluralistic nature of democratic societies, ensuring that diverse voices and perspectives are represented in the political process.

Characteristics of Political Parties and Pressure Groups

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political Parties: Organized groups that seek to attain and exercise political power through electoral processes. Pressure Groups: Organized groups that seek to influence government policies and decisions without directly seeking political office. |

| Primary Goal | Political Parties: To gain control of government and implement their ideology/agenda. Pressure Groups: To influence government policies and decisions on specific issues. |

| Membership | Political Parties: Typically have a broad membership base open to the public. Pressure Groups: Membership can be open or restricted, often focused on specific interests or causes. |

| Structure | Political Parties: Highly structured with hierarchical leadership, formal rules, and defined roles. Pressure Groups: Structure varies, ranging from loosely organized networks to formal organizations with leadership. |

| Funding | Political Parties: Funded through membership fees, donations, and public funding in some cases. Pressure Groups: Funded through membership fees, donations, grants, and sometimes corporate sponsorship. |

| Methods of Influence | Political Parties: Contest elections, form governments, propose legislation, and control policy implementation. Pressure Groups: Lobbying, advocacy, protests, media campaigns, research, and legal action. |

| Scope of Influence | Political Parties: Aim for broad policy changes and control over government. Pressure Groups: Focus on specific issues or policy areas, seeking targeted changes. |

| Accountability | Political Parties: Accountable to voters through elections and public scrutiny. Pressure Groups: Accountable to their members and donors, but less directly accountable to the general public. |

| Examples | Political Parties: Democratic Party (USA), Conservative Party (UK), Bharatiya Janata Party (India). Pressure Groups: Sierra Club (environmental), National Rifle Association (NRA, gun rights), Amnesty International (human rights). |

| Relationship with Government | Political Parties: Can form the government or be in opposition. Pressure Groups: Operate outside the government, seeking to influence it from the outside. |

| Longevity | Political Parties: Often long-lasting institutions with established histories. Pressure Groups: Can be temporary or long-term, depending on the issue and goals. |

| Ideology | Political Parties: Typically associated with a specific ideology or set of principles. Pressure Groups: May or may not have a specific ideology, often focused on practical goals. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Role: Distinguishing political parties and pressure groups in democratic systems

- Formation and Structure: How these groups organize and operate internally

- Functions and Goals: Their roles in policy-making and public influence

- Relationship with Government: Interaction between these groups and state institutions

- Impact on Democracy: Contributions to political participation and representation

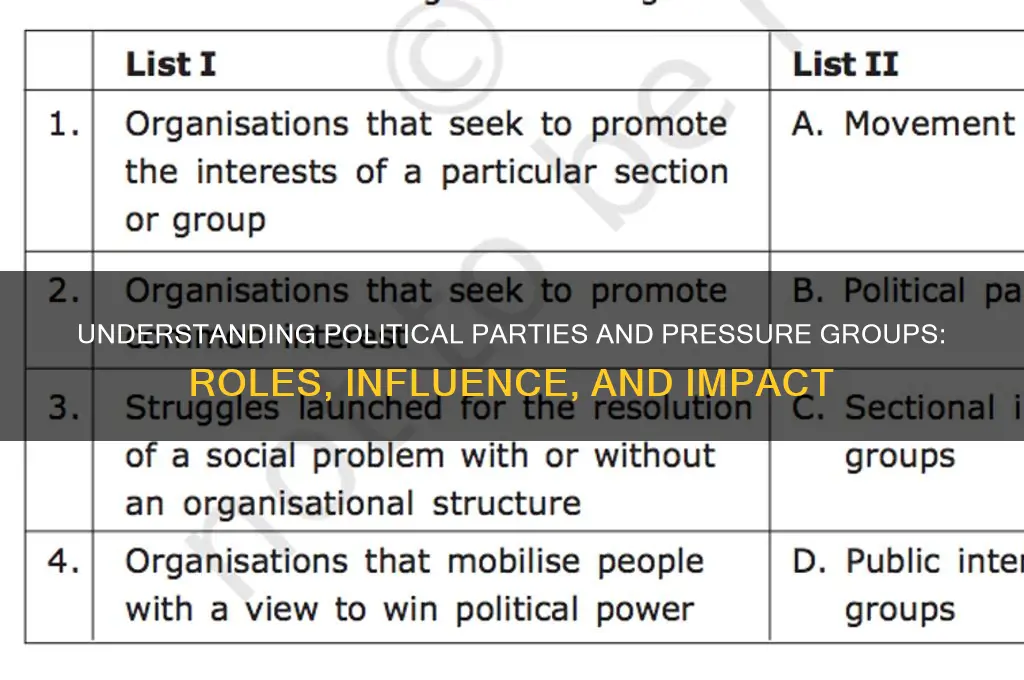

Definition and Role: Distinguishing political parties and pressure groups in democratic systems

Political parties and pressure groups are distinct yet interconnected entities within democratic systems, each serving unique functions that shape governance and policy-making. Political parties are organized groups that contest elections, aim to gain political power, and implement their ideologies through governance. In contrast, pressure groups, also known as interest groups, operate outside formal political structures, advocating for specific causes or policies without seeking direct control of government. Understanding their definitions and roles is crucial for grasping how democratic systems balance representation and advocacy.

Consider the structural differences: political parties are hierarchical, with leaders, members, and a clear chain of command, while pressure groups often operate as networks or coalitions, allowing for more flexible and issue-specific mobilization. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States is a political party with a defined platform and elected officials, whereas the Sierra Club is a pressure group focused solely on environmental conservation. This distinction highlights how parties aim for broad governance, while pressure groups target narrow, often specialized, objectives.

Analytically, the roles of these entities reveal their complementary yet divergent impacts on democracy. Political parties aggregate diverse interests into coherent platforms, fostering stability and accountability through electoral processes. Pressure groups, however, amplify specific voices that might otherwise be marginalized, acting as a check on party dominance and ensuring niche concerns are addressed. For example, while a political party might propose a comprehensive healthcare plan, a pressure group like the American Heart Association could lobby for specific provisions related to cardiovascular research funding.

Practically, distinguishing between these groups helps citizens engage effectively with democratic systems. Joining a political party allows individuals to influence broad policy directions and leadership, whereas participating in a pressure group enables targeted advocacy on issues of personal importance. For instance, a voter concerned about climate change might join the Green Party to support systemic environmental policies, while also becoming a member of Greenpeace to advocate for immediate actions like banning single-use plastics.

In conclusion, while political parties and pressure groups both contribute to democratic vitality, their roles are fundamentally different. Parties seek power to govern, whereas pressure groups seek influence to shape policy. Recognizing this distinction empowers citizens to navigate democratic systems more strategically, ensuring their voices are heard through both broad and specific channels. By understanding these roles, individuals can better align their political engagement with their goals, whether they aim to reshape governance or advocate for particular causes.

Divisive Politics: Unraveling the Roots of Hatred in Modern Society

You may want to see also

Formation and Structure: How these groups organize and operate internally

Political parties and pressure groups are the backbone of democratic systems, but their internal organization often remains a mystery to outsiders. At their core, these groups are structured to maximize influence, whether through electoral success or policy advocacy. Formation typically begins with a shared ideology or goal, attracting individuals who coalesce around a common cause. For political parties, this often involves registering with electoral bodies, drafting a party constitution, and establishing a leadership hierarchy. Pressure groups, on the other hand, may start as informal networks, gradually formalizing into registered organizations with defined roles and objectives. Both types of groups rely on a clear division of labor to function effectively, ensuring that tasks like fundraising, membership recruitment, and policy development are handled by specialized teams.

Consider the internal structure of a political party, which often mirrors a corporate organization. At the top is the party leadership, typically elected by members or delegates, who set the strategic direction and make high-level decisions. Below them are regional or local chapters, each with their own leaders and committees responsible for grassroots mobilization and campaign activities. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States has a National Committee that oversees party operations, while state and county committees handle local elections and voter outreach. This hierarchical structure ensures accountability and coordination, but it can also lead to power struggles between national and local factions. Practical tip: When joining a political party, start at the local level to understand its dynamics before aiming for higher positions.

Pressure groups, in contrast, often adopt flatter, more flexible structures to adapt to their advocacy needs. Many operate as member-driven organizations, with decisions made through consensus or majority vote at general meetings. For example, Greenpeace, an environmental pressure group, has a decentralized structure with national and regional offices that coordinate campaigns but maintain autonomy in their operations. This model allows for rapid response to emerging issues but can sometimes lead to inconsistencies in messaging or strategy. A key takeaway is that pressure groups prioritize agility over hierarchy, making them effective at mobilizing public opinion quickly.

Internal operations in both political parties and pressure groups are heavily dependent on resources, particularly funding and human capital. Political parties often rely on membership dues, donations, and public funding, with strict regulations governing financial transparency. Pressure groups, meanwhile, may depend on grants, crowdfunding, or corporate sponsorships, which can influence their independence. For instance, a pressure group funded by a specific industry may face accusations of bias, highlighting the importance of diverse revenue streams. Practical advice: Always scrutinize the funding sources of a group to understand its potential biases and priorities.

Finally, the success of these groups hinges on their ability to balance internal democracy with operational efficiency. Political parties must navigate the tension between grassroots participation and centralized decision-making, often using mechanisms like primaries or caucuses to involve members in candidate selection. Pressure groups, on the other hand, may use digital platforms to engage members in decision-making, ensuring that their actions reflect the will of the majority. For example, the UK-based pressure group 38 Degrees uses online polls to determine which campaigns to pursue, fostering a sense of ownership among its members. This blend of inclusivity and efficiency is crucial for maintaining legitimacy and achieving long-term goals.

Mahmoud Abbas' Political Affiliation: Fatah Party Leadership Explained

You may want to see also

Functions and Goals: Their roles in policy-making and public influence

Political parties and pressure groups are the architects of public policy, each wielding distinct tools to shape governance. Parties, often structured hierarchies, compete for electoral power, translating their platforms into legislation once in office. Pressure groups, by contrast, operate outside formal political structures, leveraging advocacy, lobbying, and mobilization to influence policymakers. While parties aim to govern, pressure groups seek to persuade, creating a dynamic interplay that drives policy agendas.

Consider the healthcare debate in the United States. Political parties like the Democrats and Republicans propose competing frameworks—universal coverage versus market-based solutions—and enact policies when in power. Pressure groups, such as the American Medical Association or AARP, amplify specific concerns, like physician reimbursement rates or Medicare benefits, shaping the nuances of legislation. This division of labor highlights how parties provide broad direction, while pressure groups ensure targeted issues are addressed.

To maximize influence, pressure groups employ strategic tactics: direct lobbying, grassroots campaigns, and litigation. For instance, environmental groups like Greenpeace use public protests and media campaigns to sway public opinion, while industry associations like the Chamber of Commerce engage in behind-the-scenes lobbying. Political parties, meanwhile, rely on voter mobilization and coalition-building, as seen in the 2020 U.S. elections, where both major parties targeted youth and minority voters to secure policy mandates.

A critical takeaway is the symbiotic yet adversarial relationship between these entities. Parties need pressure groups to stay attuned to public demands, while pressure groups rely on parties to enact their agendas. However, this relationship can lead to policy gridlock or capture, as seen in the influence of pharmaceutical lobbyists on drug pricing legislation. Balancing these dynamics requires transparency, robust public engagement, and institutional checks to ensure policies serve the broader public interest.

In practice, individuals and organizations can engage effectively by understanding these roles. Joining a political party offers a pathway to shape its platform, while aligning with pressure groups allows for focused advocacy. For example, a small business owner might join a local chamber of commerce to influence tax policy, while also participating in a party’s economic committee to advocate for broader reforms. By navigating these structures strategically, stakeholders can amplify their voice in the policy-making process.

Exploring the Political Affiliation of Canada's Former PM Stephen Harper

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Relationship with Government: Interaction between these groups and state institutions

Political parties and pressure groups are integral to democratic systems, serving as intermediaries between citizens and the state. Their relationship with government is dynamic, often marked by collaboration, negotiation, and occasional conflict. This interaction is crucial for policy formulation, representation, and accountability. Understanding how these groups engage with state institutions reveals the mechanics of power and influence in governance.

Consider the role of political parties in legislative processes. Parties act as organized vehicles for political participation, aggregating interests and translating them into policy proposals. For instance, in parliamentary systems, the ruling party drives the government’s agenda, while opposition parties scrutinize and challenge its actions. This adversarial yet constructive relationship ensures checks and balances. Pressure groups, on the other hand, operate outside formal government structures but wield influence through advocacy, lobbying, and mobilization. Their engagement with state institutions often involves presenting evidence, framing issues, and leveraging public opinion to shape policy outcomes. For example, environmental NGOs have successfully pushed governments to adopt stricter climate regulations by combining scientific data with grassroots campaigns.

The interaction between these groups and state institutions is not without challenges. Political parties may prioritize partisan interests over public welfare, leading to gridlock or biased policies. Pressure groups, particularly well-funded ones, can disproportionately influence decision-making, raising concerns about equity and transparency. Governments must navigate these dynamics carefully, ensuring that diverse voices are heard while maintaining the integrity of the decision-making process. A practical tip for policymakers is to establish clear guidelines for lobbying activities and foster inclusive platforms for dialogue, such as public consultations or advisory councils.

Comparatively, the relationship varies across political systems. In pluralist democracies, multiple parties and pressure groups compete for influence, fostering a vibrant but fragmented political landscape. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often suppress these groups, limiting their ability to engage with state institutions. Hybrid systems exhibit a mix of cooperation and coercion, with governments selectively engaging or marginalizing these actors. Analyzing these differences highlights the importance of institutional design in shaping the nature of interaction.

To maximize the positive impact of this relationship, governments should adopt a proactive approach. This includes strengthening regulatory frameworks to prevent undue influence, investing in capacity-building for smaller or marginalized groups, and leveraging technology to enhance transparency and participation. For instance, digital platforms can facilitate real-time feedback from citizens and pressure groups, ensuring that their voices inform policy decisions. By fostering a balanced and inclusive interaction, governments can harness the potential of political parties and pressure groups to advance public interest and democratic governance.

Charities and Politics: Ethical Boundaries of Supporting Political Parties

You may want to see also

Impact on Democracy: Contributions to political participation and representation

Political parties and pressure groups are often the lifeblood of democratic systems, serving as conduits for citizen engagement and representation. By aggregating interests and mobilizing voters, these entities ensure that diverse voices are heard in the political arena. For instance, in the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties dominate the political landscape, while pressure groups like the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the Sierra Club advocate for specific causes. This dual structure fosters a dynamic environment where both broad ideologies and niche concerns find expression.

Consider the role of political parties in simplifying complex political choices for voters. Parties act as "information shortcuts," allowing citizens to align with a set of policies and values without needing to research every issue individually. This function is particularly critical in modern democracies, where the sheer volume of information can overwhelm voters. For example, a voter in Germany might identify with the Green Party’s focus on environmental sustainability, using this affiliation as a guide for their electoral decisions. Without such frameworks, voter apathy and disengagement could undermine democratic participation.

Pressure groups, on the other hand, complement political parties by providing avenues for targeted advocacy. Unlike parties, which seek to govern, pressure groups focus on influencing policy outcomes. Take the case of the UK-based organization Greenpeace, which has successfully pressured governments to adopt stricter climate regulations. Such groups often amplify underrepresented voices, ensuring that democracy is not just about majority rule but also about protecting minority rights and interests. However, their effectiveness depends on strategic mobilization and access to decision-makers, highlighting the need for transparency and accountability in their operations.

A critical takeaway is that both political parties and pressure groups enhance democracy by fostering inclusivity and responsiveness. Parties encourage mass participation by organizing voters around shared ideologies, while pressure groups provide platforms for specialized interests. Yet, their impact is not without challenges. Parties can become elitist, prioritizing internal power struggles over public interests, and pressure groups may wield disproportionate influence through lobbying. To maximize their democratic contributions, citizens must remain vigilant, engaging critically with these institutions and holding them accountable for their actions.

Practical steps for individuals to leverage these entities include joining local party chapters, participating in pressure group campaigns, and using social media to amplify collective demands. For instance, a young activist in India could join the Congress Party’s youth wing while simultaneously collaborating with climate advocacy groups like Fridays for Future. By diversifying their engagement, citizens can ensure that their participation strengthens democracy’s foundations, making it more participatory and representative. Ultimately, the health of a democracy hinges on the active involvement of its people within these structures.

Unveiling Political Realities: Truth, Deception, and Power Dynamics Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties are organized groups of people who share common political goals and ideologies. They aim to gain political power through elections, influence government policies, and represent the interests of their supporters.

Pressure groups, also known as interest groups, are organizations that seek to influence government policies and decisions without directly seeking political power. They advocate for specific causes or interests, often representing particular sectors of society.

Political parties aim to win elections and form governments, while pressure groups focus on influencing policymakers without contesting elections. Parties represent broader ideologies, whereas pressure groups advocate for specific issues or interests.

Yes, individuals can be members of both a political party and a pressure group. While political parties focus on broader governance, pressure groups allow individuals to advocate for specific causes they are passionate about.