Political office bearers are individuals elected or appointed to hold positions of authority within a government or political organization, tasked with the responsibility of making and implementing policies that affect the public. These roles range from local positions, such as mayors or council members, to national positions like presidents, prime ministers, or legislators. Office bearers are expected to represent the interests of their constituents, uphold the principles of their political party (if affiliated), and ensure the efficient functioning of governance. Their duties often include lawmaking, budgeting, oversight, and public service, requiring a combination of leadership, integrity, and accountability to maintain public trust and address societal needs effectively.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Individuals elected or appointed to hold positions within a political party or government, responsible for making decisions, implementing policies, and representing constituents. |

| Roles | Leadership, policy-making, administration, representation, advocacy, and governance. |

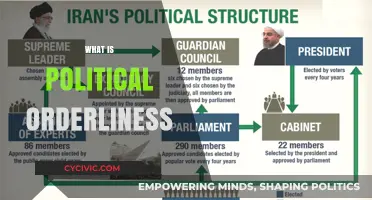

| Types | Executive (e.g., President, Prime Minister), Legislative (e.g., Members of Parliament, Senators), Judicial (e.g., Judges), and Party Officials (e.g., Chairpersons, Secretaries). |

| Responsibilities | Formulating laws, managing public resources, ensuring accountability, addressing public concerns, and upholding the constitution. |

| Accountability | Answerable to constituents, party members, and legal frameworks; subject to elections, recalls, or impeachment. |

| Tenure | Fixed terms (e.g., 4-5 years) or until resignation/removal, depending on the position and jurisdiction. |

| Qualifications | Varies by country; often includes age, citizenship, residency, and sometimes educational or professional requirements. |

| Powers | Authority to make binding decisions, allocate budgets, appoint officials, and represent the state in national/international affairs. |

| Ethics | Expected to maintain integrity, transparency, and avoid conflicts of interest; bound by codes of conduct or oaths of office. |

| Examples | Mayors, Governors, Ministers, Party Leaders, and Members of Legislative Assemblies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Roles and Responsibilities: Duties, powers, and expectations of individuals holding political positions within an organization or government

- Election Processes: Methods and procedures for selecting political office bearers, including voting systems

- Term Limits: Duration of service, restrictions, and rules governing tenure in political offices

- Accountability Mechanisms: Systems ensuring office bearers act transparently, ethically, and in public interest

- Qualifications and Eligibility: Criteria required to hold political office, such as age, citizenship, or experience

Roles and Responsibilities: Duties, powers, and expectations of individuals holding political positions within an organization or government

Political office bearers are the backbone of any organized governance structure, whether in a government or an organization. Their roles are multifaceted, blending leadership, decision-making, and representation. At the core, these individuals are entrusted with the power to shape policies, allocate resources, and advocate for the interests of their constituents. However, this power is not absolute; it is bounded by duties, ethical expectations, and accountability mechanisms. Understanding the balance between authority and responsibility is crucial for effective governance.

Consider the duties of a political office bearer. These often include legislative responsibilities, such as drafting and voting on laws, and executive functions, like implementing policies or overseeing administrative tasks. For instance, a mayor must ensure public services like waste management and transportation run smoothly, while a senator might focus on crafting bills that address national issues. Each role demands a unique skill set, from negotiation and communication to strategic planning. Failure to fulfill these duties can erode public trust and hinder organizational progress.

The powers granted to political office bearers are both a privilege and a liability. These powers vary widely depending on the position—a president may have the authority to declare a state of emergency, while a local council member might only approve zoning changes. The key lies in exercising these powers judiciously, avoiding overreach or abuse. For example, a leader who uses their authority to suppress dissent undermines democratic principles, whereas one who leverages it to foster inclusivity strengthens societal cohesion. The expectation is clear: power must serve the greater good, not personal interests.

Expectations placed on political office bearers are often unspoken yet deeply ingrained. Constituents expect transparency, integrity, and responsiveness. Organizations demand alignment with their mission and values. For instance, a board member of a nonprofit is expected to prioritize the organization’s goals over personal gain, even if it means making unpopular decisions. Similarly, a government official is held to high ethical standards, with conflicts of interest scrutinized heavily. These expectations are not always easy to meet, but they are non-negotiable for maintaining legitimacy.

In practice, balancing duties, powers, and expectations requires constant vigilance and self-awareness. Political office bearers must navigate complex landscapes, often under public scrutiny. A practical tip is to establish clear accountability frameworks, such as regular performance reviews or public reporting mechanisms. Additionally, fostering open communication with stakeholders can help align actions with expectations. Ultimately, the success of a political office bearer hinges on their ability to lead with integrity, act with purpose, and remain accountable to those they serve.

Politics and War: Unraveling the Complex Interplay of Power and Conflict

You may want to see also

Election Processes: Methods and procedures for selecting political office bearers, including voting systems

Political office bearers are individuals elected or appointed to represent and govern constituencies, from local councils to national parliaments. The methods and procedures for selecting these leaders vary widely, reflecting diverse cultural, historical, and political contexts. At the heart of these processes are election systems, which determine how votes are cast, counted, and translated into representation. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for ensuring fair, transparent, and democratic outcomes.

Voting Systems: A Comparative Overview

One of the most critical aspects of election processes is the voting system employed. Common systems include First-Past-The-Post (FPTP), Proportional Representation (PR), and Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV). FPTP, used in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, awards victory to the candidate with the most votes in a single round, often leading to majority rule but sometimes marginalizing smaller parties. In contrast, PR systems, such as those in Germany and Israel, allocate seats in proportion to the vote share, fostering coalition governments and greater representation of minority groups. RCV, used in Australia and some U.S. cities, allows voters to rank candidates, ensuring winners have broader support by eliminating the least popular candidates in rounds. Each system has trade-offs: FPTP is simple but can lead to "wasted votes," PR promotes inclusivity but may result in unstable coalitions, and RCV reduces polarization but is more complex to implement.

Steps in the Election Process: From Nomination to Declaration

The election process typically begins with candidate nomination, where individuals or parties submit their names for consideration. This is followed by campaigning, a period during which candidates engage with voters through rallies, debates, and media outreach. Voting day is the culmination of these efforts, where citizens cast their ballots in person, by mail, or electronically, depending on the jurisdiction. After polls close, votes are counted, and results are verified through audits or recounts if necessary. The final step is the declaration of results, where the winning candidate is announced and certified. Practical tips for voters include verifying registration details, understanding ballot instructions, and planning for voting day logistics, such as polling station locations and identification requirements.

Challenges and Innovations in Election Procedures

Modern election processes face challenges like voter suppression, misinformation, and technological vulnerabilities. For instance, gerrymandering in the U.S. has distorted representation by manipulating district boundaries. However, innovations are addressing these issues. Electronic voting machines and blockchain technology promise greater efficiency and security, though concerns about hacking persist. Voter education campaigns and fact-checking initiatives combat misinformation, while automatic voter registration in countries like Estonia increases participation. A key takeaway is that while technology can enhance elections, it must be implemented with safeguards to ensure integrity and accessibility.

The Role of Electoral Commissions: Guardians of Fairness

Electoral commissions are pivotal in overseeing election processes, ensuring they are free, fair, and credible. These bodies manage voter registration, candidate nomination, and result tabulation, often with legal mandates to remain impartial. For example, the Election Commission of India conducts the world’s largest democratic exercise, managing over 900 million voters. Effective commissions require independence from political influence, adequate funding, and transparency in their operations. Citizens can support their work by reporting irregularities and participating in civic education programs. Ultimately, the strength of an electoral commission reflects the health of a democracy, making its role indispensable in selecting political office bearers.

Celebrity Influence: How Stars Shape Political Narratives and Public Opinion

You may want to see also

Term Limits: Duration of service, restrictions, and rules governing tenure in political offices

Political office bearers, individuals elected or appointed to represent and govern, often face constraints on their tenure through term limits. These limits dictate the maximum duration an individual can serve in a particular office, aiming to prevent the consolidation of power and encourage fresh perspectives. For instance, the President of the United States is restricted to two four-year terms, a rule established by the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution. This example highlights how term limits are designed to balance stability with the need for periodic renewal in leadership.

Analyzing the rationale behind term limits reveals both democratic ideals and practical considerations. Proponents argue that they prevent incumbency advantages, reduce corruption, and foster a more dynamic political landscape. However, critics contend that term limits can disrupt institutional knowledge and force out effective leaders prematurely. In countries like Mexico, where legislators are limited to a single term, the focus shifts to short-term achievements rather than long-term policy development. This trade-off underscores the complexity of implementing term limits effectively.

Implementing term limits requires careful consideration of context-specific factors. For instance, in local governments, shorter terms (e.g., two years) may encourage frequent turnover, while in executive roles, longer terms (e.g., five years) can provide stability for implementing complex policies. Additionally, exceptions or extensions should be rare and justified, such as during national emergencies. For example, some African nations allow parliamentary votes to extend presidential terms, but such measures often spark controversy and allegations of power grabs.

Practical tips for designing term limits include aligning their duration with the office’s responsibilities and ensuring clarity in the rules. For instance, a mayor overseeing urban development might benefit from a four-year term, while a school board member could serve two-year terms to stay responsive to community needs. Transparency in these rules is crucial; citizens must understand when and why term limits apply. Public education campaigns and accessible legal documentation can bridge this knowledge gap.

In conclusion, term limits serve as a double-edged sword in governance, offering both opportunities and challenges. Their effectiveness hinges on thoughtful design, balancing the need for continuity with the benefits of renewal. By studying global examples and tailoring limits to specific roles, societies can harness their potential to strengthen democratic institutions while mitigating unintended consequences.

Understanding French Politics: A Comprehensive Guide to the System and Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Accountability Mechanisms: Systems ensuring office bearers act transparently, ethically, and in public interest

Political office bearers, whether elected or appointed, wield significant power and influence over public resources and policies. Ensuring they act transparently, ethically, and in the public interest is not a matter of trust alone—it requires robust accountability mechanisms. These systems serve as checks and balances, deterring misconduct and fostering public confidence in governance. Without them, even well-intentioned leaders can succumb to corruption, nepotism, or self-interest.

One cornerstone of accountability is transparency, achieved through mandatory disclosure laws. For instance, many democracies require office bearers to publicly declare their assets, income, and potential conflicts of interest upon assuming office and periodically thereafter. In South Africa, the *Executive Ethics Code* mandates annual financial disclosures for all cabinet members, which are accessible to the public. Such measures not only deter illicit enrichment but also empower citizens to scrutinize their leaders. However, transparency alone is insufficient; it must be paired with accessible platforms for citizens to engage with this information. Digital portals, like India’s *Right to Information* online platform, allow citizens to request and analyze government data, bridging the gap between disclosure and action.

Another critical mechanism is independent oversight bodies, such as anti-corruption commissions or ombudsman offices. These institutions investigate allegations of misconduct, ensuring impartiality by operating outside the influence of the executive branch. For example, Hong Kong’s *Independent Commission Against Corruption* (ICAC) has prosecutorial powers and conducts public education campaigns to foster a culture of integrity. Yet, the effectiveness of such bodies hinges on their autonomy. In countries where oversight institutions are underfunded or politically compromised, accountability remains a facade. Strengthening these bodies requires legal safeguards, adequate funding, and public support to resist political interference.

Citizen participation also plays a pivotal role in holding office bearers accountable. Public hearings, town hall meetings, and participatory budgeting processes enable direct engagement between leaders and constituents. Brazil’s *Participatory Budgeting* model, implemented in Porto Alegre, allows citizens to decide how a portion of the municipal budget is spent, reducing corruption and ensuring funds are allocated to public priorities. However, meaningful participation requires inclusivity—marginalized groups must have equal opportunities to engage. Digital tools, such as mobile surveys or online forums, can complement traditional methods, but they must be designed to bridge, not widen, the digital divide.

Finally, legal and electoral consequences serve as powerful deterrents against unethical behavior. Recall elections, as seen in some U.S. states, allow citizens to remove office bearers before their term ends if they lose public trust. Similarly, stringent anti-corruption laws, like Singapore’s *Prevention of Corruption Act*, impose severe penalties for bribery and abuse of power. Yet, these measures are only effective if enforced impartially. Judicial independence is crucial, as is public awareness of the mechanisms available to them. Without knowledge of their rights and the tools at their disposal, citizens cannot hold leaders accountable.

In conclusion, accountability mechanisms are not one-size-fits-all; they must be tailored to the political, cultural, and technological context of each society. Combining transparency, independent oversight, citizen participation, and legal consequences creates a multi-layered system that minimizes opportunities for misconduct. However, their success depends on continuous evaluation and adaptation. As power dynamics evolve, so too must the systems designed to check them. Accountability is not a static achievement but an ongoing commitment to the principles of democracy and public service.

Jimmy John's Owner Politics: Unraveling the Controversy and Impact

You may want to see also

Qualifications and Eligibility: Criteria required to hold political office, such as age, citizenship, or experience

Political office bearers are the backbone of democratic governance, but not everyone is eligible to hold these positions. The qualifications and eligibility criteria are designed to ensure that those in power are capable, responsible, and aligned with the nation’s interests. These criteria vary widely across countries but typically revolve around age, citizenship, and experience. For instance, in the United States, a presidential candidate must be at least 35 years old, a natural-born citizen, and a resident for 14 years. Such requirements are not arbitrary; they reflect a balance between inclusivity and the need for maturity and commitment.

Age is one of the most universal eligibility criteria for political office. It serves as a proxy for life experience and judgment, though its thresholds differ significantly. In India, members of the Lok Sabha must be 25 or older, while in the European Parliament, candidates need only be 18. This variation highlights differing cultural and legal perspectives on when individuals are deemed ready for public leadership. Younger democracies often set lower age limits to encourage youth participation, while older systems may prioritize experience. Understanding these age requirements is crucial for aspiring politicians, as they dictate when one can legally enter the political arena.

Citizenship is another non-negotiable criterion, though its interpretation varies. Most countries require candidates to be citizens, but the type of citizenship matters. For example, the U.S. Constitution mandates that presidents be natural-born citizens, a rule that has sparked debates about eligibility in recent years. In contrast, countries like Canada allow naturalized citizens to run for office, provided they meet residency requirements. This distinction underscores the tension between national identity and inclusivity. Prospective candidates must carefully review their country’s citizenship laws to avoid disqualification, as even minor discrepancies can derail a political career.

Experience, while not always a formal requirement, is often an unspoken criterion for political office. Voters and parties alike tend to favor candidates with a track record in public service, business, or community leadership. For instance, many U.S. senators and representatives have backgrounds in law, military service, or state politics. This preference for experience reflects a desire for competence and familiarity with governance. However, it can also create barriers for newcomers, particularly those from marginalized groups. Aspiring politicians should focus on building a resume that demonstrates leadership and problem-solving skills, even if formal experience is not mandatory.

Finally, eligibility criteria are not static; they evolve with societal norms and political realities. For example, the push for gender equality has led some countries to introduce quotas or incentives for female candidates. Similarly, debates about term limits and financial disclosures reflect growing demands for accountability. Staying informed about these changes is essential for anyone seeking political office. While the core requirements of age, citizenship, and experience remain foundational, their application continues to adapt to the needs of modern democracies. Understanding this dynamic landscape ensures that candidates are not only eligible but also well-prepared to serve effectively.

Jesus and Politics: Exploring His Role in Societal Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political office bearer is an individual who holds a formal position within a political party or government, often elected or appointed to represent the party's interests and carry out specific duties.

Political office bearers have various roles, including policy formulation, decision-making, representing their party in public forums, mobilizing supporters, and ensuring the party's agenda is implemented effectively.

The selection process varies; some are elected through internal party elections, while others are appointed by party leaders or elected by the general public in government positions.

Generally, political office bearers are members of a political party who have demonstrated commitment, leadership skills, and alignment with the party's ideology. Eligibility criteria may vary depending on the party and position.

A political office bearer primarily serves their political party, while a government official holds a public office and is responsible for administering and implementing government policies, often serving the broader public interest.