Political nationalism is a powerful ideology that centers on the belief in the nation as the primary unit of political organization, emphasizing loyalty to one's nation and often advocating for its sovereignty, cultural unity, and self-determination. Rooted in shared history, language, ethnicity, or territory, it seeks to promote national identity and interests above other affiliations, sometimes leading to the formation of independent states or the protection of existing ones. While it can foster unity and pride, political nationalism can also manifest as exclusionary or aggressive, particularly when it prioritizes the rights of a dominant group over others, raising questions about its compatibility with diversity, global cooperation, and human rights. Its impact varies widely, shaping policies, conflicts, and social dynamics across the globe.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| State Sovereignty | Emphasis on the independence and autonomy of the nation-state. |

| National Identity | Promotion of a shared culture, history, language, and ethnicity. |

| Patriotism | Strong love and loyalty towards one's nation. |

| Self-Determination | Belief in the right of a nation to govern itself without external control. |

| Homogeneity | Preference for cultural, ethnic, or religious uniformity within the state. |

| Exclusionary Policies | Often involves marginalizing or excluding minority or foreign groups. |

| Symbolism | Use of flags, anthems, and national heroes to foster unity and pride. |

| Economic Protectionism | Support for policies that prioritize national economic interests. |

| Historical Revisionism | Reinterpretation of history to glorify the nation and its achievements. |

| Political Mobilization | Use of nationalism to rally support for political agendas or leaders. |

| Territorial Integrity | Strong defense of national borders and territories. |

| Anti-Imperialism | Opposition to foreign domination or interference in national affairs. |

| Cultural Preservation | Efforts to protect and promote traditional customs and practices. |

| Populism | Appeals to the common people against elites or external threats. |

| Military Strength | Emphasis on building a strong military to defend national interests. |

| Global Influence | Aspiration to enhance the nation's power and prestige on the world stage. |

Explore related products

$14.98 $19.99

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Nationalism's roots in 19th-century Europe, tied to revolutions and state formation

- Cultural Identity: Shared language, traditions, and heritage as foundations of national unity

- Political Movements: Nationalism's role in independence struggles and state-building efforts globally

- Ethnic vs. Civic: Distinction between ethnicity-based and inclusive, citizenship-focused nationalist ideologies

- Modern Challenges: Nationalism's impact on globalization, migration, and multicultural societies today

Historical Origins: Nationalism's roots in 19th-century Europe, tied to revolutions and state formation

The 19th century in Europe was a crucible for political nationalism, as revolutions and state formation intertwined to forge modern nations. The French Revolution (1789–1799) laid the groundwork by popularizing the idea of popular sovereignty and civic identity, challenging the old order of monarchies and feudalism. Its slogan, *Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité*, resonated beyond France, inspiring movements across the continent. Yet, it was the Napoleonic Wars that spread these ideals further, dismantling traditional structures and planting the seeds of national consciousness in territories from Germany to Italy. This period marked the shift from dynastic loyalties to a shared cultural and political identity, setting the stage for nationalism’s rise.

Consider the role of intellectuals and artists in shaping national narratives. In Germany, figures like Johann Gottfried Herder argued that language and culture were the essence of a nation, not political boundaries. This cultural nationalism fueled the unification of German states under Prussia in 1871, a process driven by Otto von Bismarck’s *Realpolitik*. Similarly, in Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy movement and Giuseppe Garibaldi’s military campaigns galvanized the populace around the idea of a unified Italian state, culminating in the Risorgimento. These examples illustrate how intellectual and cultural movements provided the ideological backbone for political nationalism, turning abstract ideas into concrete political goals.

Revolutions were the catalysts that transformed these ideas into reality. The Revolutions of 1848, often called the "Spring of Nations," saw uprisings across Europe demanding constitutional reforms, national self-determination, and independence. While many of these revolts were suppressed, they demonstrated the power of nationalist sentiment to mobilize masses. In Hungary, for instance, Lajos Kossuth’s fight for independence from the Austrian Empire became a symbol of resistance. These events underscored that nationalism was not merely a philosophical concept but a force capable of reshaping political landscapes, often through violent struggle.

State formation in the 19th century was both a cause and consequence of nationalism. Newly formed nations like Belgium (1830) and Greece (1832) emerged from successful nationalist revolts, while others, like Germany and Italy, were unified through strategic political maneuvering. The creation of these states often involved redrawing borders, standardizing languages, and fostering a shared national identity through education and media. However, this process was not without contradictions. Imperial powers like Britain and France used nationalism to justify colonial expansion, claiming a civilizing mission for their "superior" nations. This duality highlights how nationalism could be both a tool for liberation and domination, depending on who wielded it.

Understanding the historical origins of nationalism in 19th-century Europe offers a lens to analyze its modern manifestations. The interplay of revolutions, intellectual movements, and state formation reveals how nationalism was constructed and contested. It was not an inevitable force but a product of specific historical conditions, shaped by the struggles and aspirations of diverse peoples. By studying this period, we can better grasp the complexities of nationalism today, recognizing its potential to unite and divide, liberate and oppress. This history serves as a reminder that nations, like all political constructs, are not eternal but are continually made and remade through human action.

Evaluating FiveThirtyEight's Political Predictions: Accuracy and Reliability Explored

You may want to see also

Cultural Identity: Shared language, traditions, and heritage as foundations of national unity

Language, the bedrock of human connection, becomes a powerful tool in the hands of political nationalism. A shared tongue fosters a sense of belonging, a collective "us" against a perceived "them." Consider the Basque language, Euskara, spoken in a region straddling Spain and France. Despite centuries of suppression, its preservation has become a rallying cry for Basque nationalism, a symbol of resistance and a unique cultural identity. This example illustrates how language, far beyond mere communication, can become a political weapon, uniting a people around a common cause.

Recognizing this power, nationalist movements often prioritize language revival and standardization. They may promote its use in education, media, and government, effectively creating a linguistic barrier that reinforces the boundaries of the nation. While this can foster a strong sense of community, it can also lead to the marginalization of minority languages and dialects, raising concerns about cultural homogenization and the suppression of diversity.

Traditions, woven into the fabric of daily life, provide another cornerstone for national unity. Shared customs, festivals, and rituals create a sense of continuity and shared history. Take the Japanese tea ceremony, a highly ritualized practice steeped in Zen Buddhism and aesthetic principles. Beyond its cultural significance, it has been used to promote a sense of Japanese uniqueness and superiority, particularly during periods of intense nationalism. This highlights the dual nature of traditions: they can be both a source of cultural pride and a tool for exclusion, reinforcing a narrative of "us" versus "them."

It's crucial to approach the role of traditions in nationalism with a critical eye. While they can foster a sense of belonging, they can also be manipulated to exclude and marginalize. Nationalist movements often selectively interpret and promote traditions, emphasizing those that fit their narrative while downplaying or erasing others. This selective memory can lead to a distorted view of history and a narrow definition of national identity.

Heritage, the tangible and intangible legacy of the past, provides a powerful narrative for nationalist movements. Monuments, historical sites, and cultural artifacts become symbols of a shared past, rallying points for national pride. The Taj Mahal, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, stands as a testament to Mughal architecture and a symbol of India's rich cultural heritage. However, its significance extends beyond aesthetics; it has been used in political discourse to promote a particular vision of Indian identity, often excluding the contributions of other cultures and communities. This example underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of heritage, recognizing its potential for both unity and division.

Ultimately, the interplay of language, traditions, and heritage in shaping national identity is complex and multifaceted. While they can be powerful forces for unity, they can also be wielded as tools of exclusion and domination. A critical awareness of this dynamic is essential for navigating the complexities of political nationalism and fostering a more inclusive and equitable understanding of cultural identity.

Understanding Political Inclusion: Empowering Diverse Voices in Democracy

You may want to see also

Political Movements: Nationalism's role in independence struggles and state-building efforts globally

Nationalism has been a driving force in numerous independence struggles and state-building efforts across the globe, shaping the political landscape of the modern world. From the 19th-century unification of Germany and Italy to the 20th-century decolonization movements in Africa and Asia, nationalist sentiments have fueled the desire for self-governance and cultural autonomy. These movements often emerged as a response to foreign domination, economic exploitation, or cultural suppression, uniting diverse populations under a common identity. For instance, the Indian independence movement, led by figures like Mahatma Gandhi, harnessed nationalist fervor to challenge British colonial rule, ultimately leading to the creation of an independent Indian state in 1947.

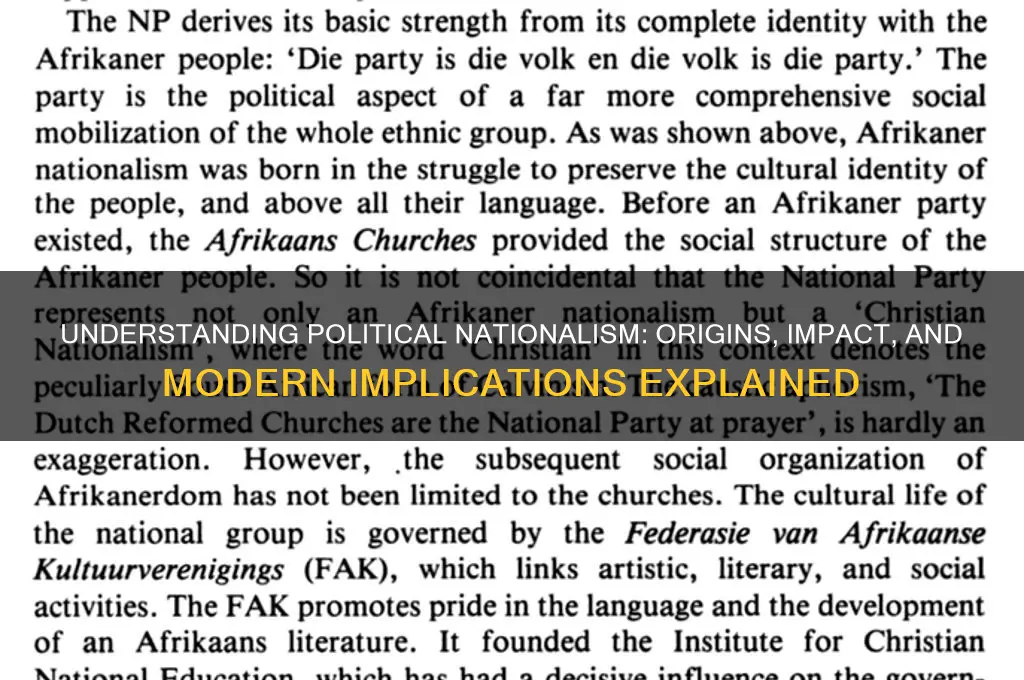

Analyzing the mechanics of nationalist movements reveals a consistent pattern: the construction of a shared identity, often rooted in language, religion, ethnicity, or history, serves as the bedrock for mobilization. In the case of the Zionist movement, Jewish nationalism was instrumental in the establishment of Israel in 1948, driven by the aspiration for a Jewish homeland after centuries of diaspora. Similarly, the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s was marked by competing nationalisms—Serbian, Croatian, and others—each vying for statehood and self-determination. These examples illustrate how nationalism can both unite and divide, depending on its framing and the context in which it operates.

However, the role of nationalism in state-building is not without challenges. While it can foster unity and purpose, it can also lead to exclusionary policies and conflicts. In Rwanda, for example, extremist interpretations of Hutu nationalism fueled the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi population, demonstrating the destructive potential of unchecked nationalist ideologies. Conversely, inclusive forms of nationalism, such as those seen in post-apartheid South Africa, have been pivotal in fostering reconciliation and nation-building. Nelson Mandela’s emphasis on a "Rainbow Nation" sought to transcend racial divisions, illustrating how nationalism can be harnessed for constructive ends.

To effectively leverage nationalism in independence struggles and state-building, leaders must navigate its dual nature. Practical steps include fostering a civic nationalism that emphasizes shared values and institutions over ethnic or religious exclusivity. For instance, countries like Switzerland have successfully managed diverse populations by promoting a national identity based on democracy, neutrality, and federalism. Caution must be exercised, however, to avoid the pitfalls of ethnonationalism, which often marginalizes minority groups and undermines social cohesion. Policymakers should prioritize inclusive education, equitable resource distribution, and legal frameworks that protect minority rights to ensure nationalism serves as a unifying rather than divisive force.

In conclusion, nationalism remains a potent tool in political movements, particularly in the context of independence struggles and state-building. Its ability to mobilize populations and forge collective identities is unparalleled, yet its potential for exclusion and conflict demands careful management. By studying historical examples and adopting inclusive strategies, nations can harness the positive aspects of nationalism to build stable, cohesive societies. The key lies in balancing the aspirations of the majority with the rights of the minority, ensuring that nationalist movements contribute to progress rather than peril.

Understanding Political Image: Crafting Public Perception in Modern Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

Ethnic vs. Civic: Distinction between ethnicity-based and inclusive, citizenship-focused nationalist ideologies

Nationalism, as a political ideology, manifests in two distinct forms: ethnic and civic. These variants diverge fundamentally in their definitions of national identity and membership. Ethnic nationalism anchors identity in shared heritage, culture, language, or religion, often excluding those who do not fit this predefined mold. In contrast, civic nationalism emphasizes shared citizenship, values, and participation in a political community, fostering inclusivity regardless of ethnic background. This distinction shapes policies, societal cohesion, and the treatment of minorities, making it a critical lens for understanding modern political landscapes.

Consider the case of Germany and France, two nations with contrasting nationalist frameworks. Germany’s historical struggle with ethnic nationalism, exemplified by the Nazi regime’s emphasis on Aryan purity, led to catastrophic exclusion and violence. Post-war, Germany shifted toward a more civic model, prioritizing constitutional values and shared citizenship. France, meanwhile, has long championed civic nationalism through its *assimilationist* policies, which demand adherence to secular, republican principles over ethnic or religious identities. These examples illustrate how the choice between ethnic and civic nationalism directly impacts social integration and national unity.

To implement civic nationalism effectively, policymakers must focus on fostering a shared civic identity through education, inclusive institutions, and equitable access to rights. For instance, schools can teach a common history that acknowledges diverse contributions while emphasizing shared values like democracy and equality. Caution must be taken, however, to avoid forced assimilation, which can alienate minority groups. Instead, policies should encourage voluntary participation in civic life, such as through community service or political engagement. Practical steps include multilingual resources, cultural sensitivity training for officials, and anti-discrimination laws to ensure equal opportunities.

Persuasively, civic nationalism offers a more sustainable foundation for diverse societies. By decoupling national identity from ethnicity, it allows individuals to belong based on shared commitment to a political community rather than immutable traits. This approach not only reduces intergroup tensions but also aligns with global trends toward multiculturalism. Ethnic nationalism, while appealing to homogenous societies, risks fragmentation and conflict in pluralistic contexts. For nations grappling with diversity, adopting a civic framework is not just a moral imperative but a strategic necessity for long-term stability.

In conclusion, the distinction between ethnic and civic nationalism is not merely academic—it has tangible implications for governance, social cohesion, and human rights. While ethnic nationalism may provide a sense of rootedness, its exclusionary nature often breeds division. Civic nationalism, though challenging to implement, offers a pathway to unity in diversity. Nations must carefully navigate this divide, balancing the preservation of cultural identities with the cultivation of inclusive, participatory citizenship. The choice between these ideologies will define the character of political communities for generations to come.

Palestinian Political Prisoners: Counting the Detainees in Israeli Custody

You may want to see also

Modern Challenges: Nationalism's impact on globalization, migration, and multicultural societies today

Nationalism, once a driving force behind decolonization and self-determination, now complicates the interconnectedness fostered by globalization. Economic interdependence, a hallmark of globalization, clashes with nationalist policies prioritizing domestic industries and labor. For instance, the rise of "economic patriotism" in countries like the United States and India has led to tariffs and trade restrictions, disrupting global supply chains. This protectionist turn, while appealing to nationalist sentiments, risks fragmenting the global economy and hindering collective solutions to transnational challenges like climate change and pandemics.

Globalization's promise of a borderless world, facilitated by technological advancements, is further undermined by nationalist rhetoric that portrays international cooperation as a threat to sovereignty. This tension is evident in the resistance to global institutions like the World Trade Organization and the International Criminal Court, which are often framed as encroaching on national autonomy. As a result, the very mechanisms designed to manage globalization's complexities are weakened, leaving the world more vulnerable to crises that demand coordinated responses.

Migration, a natural consequence of globalization, has become a flashpoint for nationalist anxieties. The influx of migrants and refugees, driven by conflict, poverty, and climate change, is often portrayed as a threat to national identity and cultural homogeneity. This narrative, fueled by populist leaders, has led to the rise of anti-immigrant policies and sentiments across the globe. From the construction of border walls to the criminalization of undocumented migrants, these measures not only violate human rights but also exacerbate social divisions within multicultural societies.

Consider the case of Europe, where the refugee crisis has exposed deep fault lines between nations. While some countries, like Germany, initially adopted open-door policies, others, like Hungary and Poland, have erected physical and legal barriers. This divergence reflects the clash between the ideals of a united Europe and the resurgence of nationalist sentiments that prioritize ethnic and cultural exclusivity. The result is a continent struggling to reconcile its commitment to human rights with the political realities of nationalist backlash.

Multicultural societies, once celebrated as models of diversity and inclusion, are increasingly under pressure from nationalist ideologies. The demand for assimilation, often couched in the language of national unity, undermines the very fabric of these societies. For instance, policies targeting minority languages, religions, and cultural practices not only marginalize communities but also stifle the creative and economic benefits of diversity. In countries like France and India, debates over secularism and national identity have led to discriminatory laws and social tensions, highlighting the challenges of balancing unity with diversity.

To navigate these challenges, it is essential to reframe the narrative around nationalism and globalization. Instead of viewing them as mutually exclusive, we must recognize the potential for a more inclusive nationalism that embraces diversity and global cooperation. Practical steps include investing in education that promotes cultural understanding, implementing policies that address economic inequalities fueling nationalist sentiments, and fostering dialogue between communities. By doing so, we can harness the positive aspects of nationalism—such as pride in one's heritage—while mitigating its destructive potential. Ultimately, the goal is not to eradicate nationalism but to transform it into a force that strengthens, rather than divides, our interconnected world.

Mastering Polite Rejection: Examples for Professional and Personal Situations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political nationalism is an ideology that emphasizes the nation as the primary unit of political organization, often advocating for the interests, identity, and sovereignty of a specific national group. It seeks to align political boundaries with national or ethnic identities.

While cultural nationalism focuses on preserving and promoting a shared language, traditions, and heritage, political nationalism prioritizes the establishment or maintenance of a nation-state, often involving political autonomy or independence.

Political nationalism can lead to increased tensions between nations, the rise of populist movements, and challenges to international cooperation. It may also strengthen national identities but can sometimes result in exclusionary policies or conflicts over territory and resources.