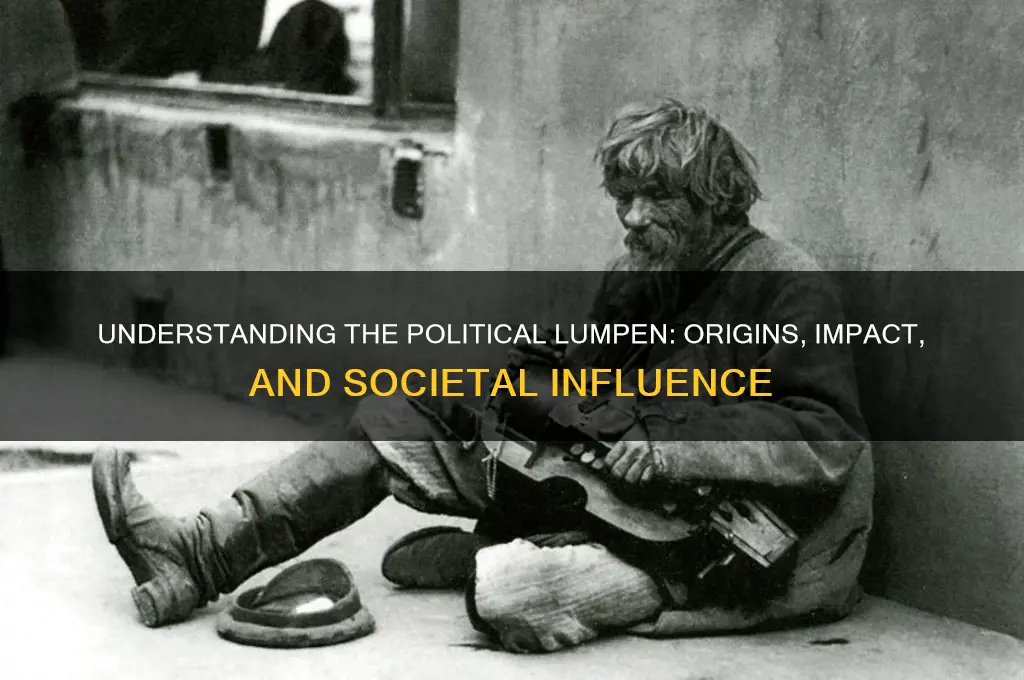

The term political lumpen refers to a segment of the population often marginalized from mainstream political and economic structures, characterized by their lack of stable employment, education, and social integration. Derived from the concept of the lumpenproletariat in Marxist theory, which describes the underclass disconnected from the productive workforce, the political lumpen is typically associated with individuals who, due to their precarious circumstances, may be more susceptible to manipulation by populist or extremist ideologies. This group often includes the unemployed, informal workers, and those living in poverty, who may feel alienated from traditional political parties and institutions. Their political behavior can be unpredictable, sometimes aligning with radical movements or authoritarian figures who promise quick solutions to their grievances. Understanding the political lumpen is crucial for analyzing contemporary political dynamics, as their mobilization can significantly influence electoral outcomes and social stability.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political lumpen refers to a marginalized or dispossessed group in society that is often exploited or manipulated by political actors, lacking a coherent ideology or class consciousness. |

| Social Position | Typically comprises the unemployed, underemployed, informal workers, and those living in poverty or precarious conditions. |

| Political Behavior | Often exhibits apathy, disengagement, or sporadic, reactive participation in politics, sometimes driven by immediate grievances rather than long-term goals. |

| Ideological Alignment | Lacks a consistent ideological stance; may be swayed by populist, extremist, or opportunistic political narratives. |

| Vulnerability to Manipulation | Highly susceptible to manipulation by political elites, demagogues, or authoritarian regimes due to economic insecurity and lack of political education. |

| Role in Political Movements | Can be mobilized as a tool for political violence, protests, or as a base for populist or authoritarian movements, often without clear understanding of broader implications. |

| Class Consciousness | Lacks a unified class identity or solidarity, making it difficult to organize for collective interests. |

| Economic Exploitation | Frequently exploited as cheap labor or used to undermine organized labor movements. |

| Historical Context | The term has roots in Marxist theory, originally referring to the "lumpenproletariat," but has evolved to describe politically marginalized groups in various contexts. |

| Contemporary Examples | Seen in contexts where economic inequality, political disenfranchisement, and social fragmentation are prevalent, such as in some developing countries or marginalized urban areas in developed nations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of the Term: Coined by Karl Marx, describing a degraded, declassed group in capitalist societies

- Characteristics: Unorganized, marginalized, often violent, lacking class consciousness or political ideology

- Role in Politics: Exploited by elites to destabilize movements or suppress progressive change

- Historical Examples: Used in fascist regimes to intimidate opponents and maintain power

- Modern Context: Associated with populist movements, often fueled by economic and social disenfranchisement

Origins of the Term: Coined by Karl Marx, describing a degraded, declassed group in capitalist societies

The term "lumpen" finds its roots in Karl Marx's critique of capitalism, specifically in his writings on class struggle and social stratification. Marx used the term "lumpenproletariat" to describe a segment of society that, unlike the traditional proletariat, lacked class consciousness and was therefore incapable of organizing for revolutionary change. This group, often composed of the unemployed, criminals, and those living on the margins of society, was seen as degraded and declassed, existing outside the productive forces of capitalism. Marx's characterization was not merely descriptive but carried a moral and political judgment, suggesting that the lumpenproletariat was not only exploited by the system but also internally divided, making it a potential tool for the ruling class to undermine revolutionary movements.

To understand Marx's concept, consider the historical context of 19th-century Europe, where industrialization was uprooting traditional social structures. The lumpenproletariat emerged as a byproduct of this upheaval, comprising individuals who could not be absorbed into the new industrial order. For instance, rural peasants displaced by enclosures, artisans rendered obsolete by mechanization, and seasonal workers without stable employment often fell into this category. Marx's analysis highlights how capitalism not only creates a working class but also generates a surplus population that is both excluded from and exploited by the system. This exclusion fosters a sense of alienation and desperation, making the lumpenproletariat susceptible to manipulation by the bourgeoisie.

Marx's critique extends beyond mere economic deprivation; it emphasizes the psychological and social degradation of the lumpenproletariat. Unlike the proletariat, which Marx saw as a unified force with a shared interest in overthrowing capitalism, the lumpenproletariat lacks solidarity and is often characterized by internal competition and fragmentation. This makes it a politically unreliable group, incapable of contributing to a coherent revolutionary movement. Marx's disdain for the lumpenproletariat is evident in his writings, where he describes them as "a mass of ruined and adventurous residuum, ready for any felony." This harsh judgment reflects his belief that true revolutionary potential lies within the organized working class, not the disorganized and marginalized lumpen.

A practical takeaway from Marx's concept is the importance of distinguishing between different social groups within capitalist societies. While the proletariat represents a collective force with the potential for transformative change, the lumpenproletariat embodies the system's failures and contradictions. Understanding this distinction is crucial for political organizers and activists, as it informs strategies for mobilization and coalition-building. For example, efforts to engage marginalized groups must address their specific needs and challenges, recognizing that their experiences differ fundamentally from those of the traditional working class. By acknowledging the origins and characteristics of the lumpenproletariat, we can develop more nuanced approaches to social and political change.

Finally, Marx's concept of the lumpenproletariat serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of exclusion and marginalization within capitalist societies. While his analysis may seem pessimistic, it underscores the need for inclusive and equitable solutions to address the root causes of social degradation. Modern interpretations of the lumpenproletariat often expand on Marx's ideas, applying them to contemporary issues such as mass incarceration, migrant labor, and the gig economy. By revisiting Marx's original framework, we can gain insights into the enduring relevance of his critique and its implications for understanding and challenging the inequalities of today's world.

Measuring Political Polarization: Methods, Metrics, and Real-World Applications

You may want to see also

Characteristics: Unorganized, marginalized, often violent, lacking class consciousness or political ideology

The political lumpen, a term often associated with the fringes of society, embodies a unique set of characteristics that set it apart from traditional political groups. At its core, this group is defined by its unorganized nature, which is not merely a lack of structure but a reflection of its members' inability or unwillingness to coalesce around a common goal. Unlike labor unions or political parties, the lumpen lacks the cohesion necessary for sustained collective action. This disorganization is both a strength and a weakness: it allows for spontaneous, unpredictable movements but limits the group's ability to achieve long-term objectives. For instance, the 2005 French riots, involving marginalized youth, demonstrated how unorganized groups can mobilize quickly but struggle to translate their energy into lasting change.

Marginalization is another defining trait, often serving as the catalyst for the lumpen's formation. These individuals are typically excluded from mainstream economic, social, and political systems, leaving them with few avenues for legitimate expression. Their marginalization is not just material but also psychological, as they internalize their exclusion and develop a sense of alienation from society. This alienation can manifest in violent outbursts, which are not always ideologically driven but rather expressions of frustration and despair. The 1992 Los Angeles riots, sparked by the acquittal of police officers in the Rodney King case, exemplify how marginalized groups can resort to violence when systemic grievances go unaddressed. Such acts are often misinterpreted as senseless, but they are deeply rooted in the lumpen's experience of neglect and oppression.

The absence of class consciousness further distinguishes the political lumpen from other marginalized groups. Unlike the proletariat, which Marx theorized as having a shared understanding of its exploitation, the lumpen lacks a collective identity or awareness of its position within the broader social hierarchy. This absence of class consciousness makes it difficult for the lumpen to articulate demands or form alliances with other groups. Instead, its actions are often reactive and fragmented, driven by immediate grievances rather than a long-term vision. For example, the Yellow Vests movement in France, while partially lumpen in nature, struggled to maintain unity due to its participants' diverse and often conflicting interests.

Compounding these characteristics is the lumpen's lack of a coherent political ideology. Unlike revolutionary groups that adhere to specific doctrines, the lumpen's actions are rarely guided by a clear ideological framework. This ideological vacuum can make the lumpen susceptible to manipulation by external forces, whether state actors or opportunistic leaders. However, it also grants the lumpen a certain unpredictability, as its actions are not constrained by dogma. The role of the lumpen in the Arab Spring, for instance, highlights this duality: while their participation was crucial in destabilizing authoritarian regimes, their lack of ideology prevented them from shaping the post-revolutionary order.

In practical terms, understanding the political lumpen requires recognizing its potential as both a force for disruption and a symptom of systemic failure. Policymakers and activists must address the root causes of marginalization, such as economic inequality and social exclusion, to mitigate the lumpen's resort to violence. At the same time, efforts to engage the lumpen should focus on fostering a sense of collective identity and purpose, even if it falls short of traditional class consciousness. For instance, community-based programs that provide marginalized youth with skills and opportunities can help channel their energy into constructive outlets. Ultimately, the lumpen's characteristics, while challenging, offer insights into the gaps within our political and social systems, urging us to reimagine inclusion and justice.

Is Curiosity Stream Politically Biased? Exploring Its Content and Perspective

You may want to see also

Role in Politics: Exploited by elites to destabilize movements or suppress progressive change

The political lumpen, often marginalized and disaffected, are prime targets for manipulation by elites seeking to maintain power. This group, characterized by its lack of stable employment, education, and social integration, is particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Elites capitalize on their desperation, offering temporary relief or false promises in exchange for actions that undermine progressive movements. For instance, during the 2020 U.S. elections, reports emerged of individuals from low-income communities being paid to disrupt protests or spread misinformation online, effectively diluting the impact of grassroots activism.

To understand this dynamic, consider the steps elites take to co-opt the lumpen. First, they identify grievances within this group, such as economic hardship or social exclusion. Second, they amplify these grievances through targeted messaging, often using divisive rhetoric to alienate the lumpen from progressive causes. Third, they provide tangible incentives—money, protection, or a sense of belonging—to encourage actions like voter suppression, violence, or propaganda dissemination. This process not only weakens progressive movements but also deepens the lumpen’s dependency on the very elites exploiting them.

A comparative analysis reveals that this strategy is not confined to any single region or ideology. In Brazil, for example, paramilitary groups linked to landowners have historically recruited lumpen elements to intimidate rural workers and activists fighting for land reform. Similarly, in post-Soviet states, oligarchs have used lumpen groups to disrupt pro-democracy protests, ensuring their continued dominance. These cases highlight a global pattern: the lumpen’s exploitation is a versatile tool for countering progressive change, adaptable to various political contexts.

To counteract this exploitation, progressive movements must adopt a two-pronged approach. First, they should actively engage the lumpen by addressing their immediate needs—job training, healthcare, and education—to reduce their vulnerability to elite manipulation. Second, movements must reframe their messaging to include the lumpen’s aspirations, emphasizing shared goals like economic equality and social justice. Practical tips include organizing community workshops, offering microloans for small businesses, and creating safe spaces for dialogue. By empowering the lumpen, progressives can neutralize their exploitation and transform them into allies for change.

Ultimately, the role of the political lumpen in destabilizing movements is not inevitable but a consequence of systemic neglect and deliberate manipulation. Recognizing this dynamic allows for strategic interventions that break the cycle of exploitation. The takeaway is clear: to achieve lasting progressive change, movements must not only challenge elites but also reclaim the marginalized, turning potential liabilities into assets in the fight for a more just society.

Is Bloomberg Inc. Shaping Politics? Analyzing Influence and Impact

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: Used in fascist regimes to intimidate opponents and maintain power

Fascist regimes have historically relied on the political lumpen—marginalized, often violent groups co-opted by the state—to enforce control through intimidation. In Mussolini’s Italy, the *squadristi*, armed gangs of former soldiers and disaffected youth, were deployed to crush socialist and unionist movements. These squads, operating outside formal law, terrorized opponents with beatings, arson, and public humiliation, creating an atmosphere of fear that silenced dissent. Their brutality was not just tactical but symbolic, demonstrating the regime’s willingness to abandon legal norms to achieve dominance.

In Nazi Germany, the Sturmabteilung (SA) and later the SS served a similar function, though with a more structured hierarchy. Initially, the SA, composed of unemployed veterans and lumpen elements, targeted communists, Jews, and other perceived enemies through street violence and pogroms. Their role was pivotal in the early stages of Nazi consolidation, as their unchecked aggression deterred opposition and rallied support from those seeking order. However, their eventual sidelining in favor of the more disciplined SS highlights a fascist regime’s need to balance raw intimidation with institutional control.

Franco’s Spain utilized the *Falange* militia, which, like its Italian and German counterparts, drew from the lumpenized segments of society. These groups were instrumental in the Spanish Civil War, executing summary killings and enforcing ideological conformity in captured territories. Post-war, they were integrated into the state apparatus, their violence legitimized as a tool of national purification. This transformation underscores how fascist regimes often transition from relying on chaotic lumpen elements to institutionalizing their terror.

A comparative analysis reveals a pattern: fascist regimes exploit the political lumpen’s alienation and propensity for violence, offering them purpose and power in exchange for loyalty. However, this alliance is inherently unstable. The lumpen’s unpredictability and lack of ideological commitment often lead regimes to replace them with more controlled forces. The takeaway is clear: while the political lumpen serves as a brutal instrument of early fascist dominance, their utility diminishes as regimes seek to stabilize their rule. Understanding this dynamic offers insights into both the rise and eventual fragility of fascist power structures.

Voltaire's Political Engagement: Satire, Philosophy, and Power Dynamics Explored

You may want to see also

Modern Context: Associated with populist movements, often fueled by economic and social disenfranchisement

The term "political lumpen" has re-emerged in contemporary discourse as a lens to understand the rise of populist movements globally. These movements, often characterized by their anti-establishment rhetoric and appeal to the marginalized, are increasingly fueled by economic and social disenfranchisement. The lumpenproletariat, traditionally defined as the underclass or unorganized poor, now finds a political voice in these populist waves, reshaping the dynamics of power and representation.

Consider the following steps to grasp the modern context of the political lumpen: First, identify the economic drivers—job losses due to automation, globalization, and austerity measures have left vast populations without stable livelihoods. Second, examine social alienation—communities excluded from mainstream political and cultural narratives seek alternatives that promise recognition and redress. Third, analyze the role of technology—social media platforms amplify grievances, fostering collective identities around shared discontent. This trifecta of factors creates fertile ground for populist leaders who capitalize on the frustrations of the lumpenized masses.

A cautionary note: While populist movements often claim to represent the voiceless, their solutions can be simplistic or divisive. For instance, scapegoating immigrants or minorities as the source of economic woes may provide temporary catharsis but exacerbates social fractures. The political lumpen, lacking organized structures or long-term vision, can be easily manipulated into supporting policies that undermine their own interests. This dynamic is evident in both left-wing and right-wing populism, where short-term emotional appeals often trump sustainable solutions.

To illustrate, examine the Yellow Vests movement in France, which began as a protest against fuel tax hikes but evolved into a broader critique of economic inequality. Similarly, in Latin America, leaders like Hugo Chávez and Jair Bolsonaro harnessed the discontent of the lumpenized to consolidate power, albeit with vastly different ideologies. These examples highlight how economic and social disenfranchisement, when politicized, can both challenge and destabilize existing systems.

In conclusion, the modern political lumpen is not merely a passive byproduct of structural inequalities but an active force in populist movements. Understanding this phenomenon requires a nuanced approach—one that acknowledges the legitimate grievances of the disenfranchised while critically evaluating the agendas of those who claim to speak for them. As populist waves continue to reshape global politics, the role of the lumpenized masses will remain a pivotal, if unpredictable, factor.

Understanding Political Censorship: Control, Suppression, and Free Speech Limits

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The term "political lumpen" refers to a group of individuals or a class that is often marginalized, unorganized, and lacks a clear political ideology or direction. It is derived from the concept of the "lumpenproletariat," a term coined by Karl Marx to describe the underclass or outcasts of society who are not part of the traditional working class.

The political lumpen differs from the traditional working class in that they are often excluded from the formal economy, lack stable employment, and are not organized into labor unions or other collective groups. They may include the unemployed, the underemployed, the homeless, and those involved in informal or illegal activities. Unlike the working class, the political lumpen is often seen as a volatile and unpredictable force in politics.

The political lumpen can play a complex and multifaceted role in political movements or revolutions. On one hand, they may be mobilized by populist or radical leaders who promise to address their grievances and provide them with a sense of belonging. On the other hand, their lack of organization and clear ideology can make them susceptible to manipulation or co-optation by powerful interests. In some cases, the political lumpen may also engage in spontaneous or chaotic forms of protest, such as riots or looting, which can both challenge and destabilize existing power structures.