Political inversion refers to the phenomenon where traditional political ideologies, roles, or power structures are flipped or reversed, often leading to unexpected alliances, policy shifts, or societal changes. This concept can manifest in various ways, such as when left-wing parties adopt conservative economic policies or when right-wing movements champion progressive social agendas. Political inversion challenges conventional political frameworks, blurring the lines between established ideologies and forcing a reevaluation of long-held beliefs. It often arises in response to crises, shifting demographics, or the rise of populist movements, highlighting the fluid and adaptive nature of political systems. Understanding political inversion is crucial for analyzing contemporary political dynamics and predicting future trends in an increasingly polarized and interconnected world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political inversion refers to the reversal or subversion of traditional political norms, structures, or ideologies, often leading to unexpected outcomes or power shifts. |

| Key Features | 1. Subversion of established norms 2. Reversal of power dynamics 3. Unexpected alliances or outcomes 4. Challenge to traditional ideologies |

| Examples | 1. Populist movements undermining elites 2. Authoritarian regimes co-opting democratic rhetoric 3. Progressive policies adopted by conservative parties |

| Causes | 1. Public disillusionment with mainstream politics 2. Economic inequality 3. Social media amplifying alternative voices 4. Globalization and cultural shifts |

| Effects | 1. Political instability 2. Polarization of societies 3. Erosion of trust in institutions 4. Emergence of new political actors |

| Recent Trends | 1. Rise of anti-establishment movements (e.g., Brexit, Trumpism) 2. Increasing use of misinformation and disinformation 3. Growing influence of non-traditional media |

| Criticisms | 1. Potential for authoritarianism 2. Risk of policy incoherence 3. Exploitation of public grievances for political gain |

| Counterarguments | 1. Can lead to necessary systemic reforms 2. Empowers marginalized voices 3. Challenges entrenched power structures |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Brief history and core concept of political inversion in governance

- Mechanisms of Inversion: How power structures are flipped or subverted in politics

- Historical Examples: Case studies of political inversion in different societies

- Causes and Triggers: Factors leading to the emergence of political inversion

- Consequences and Impact: Effects of political inversion on stability and governance

Definition and Origins: Brief history and core concept of political inversion in governance

Political inversion, as a concept, challenges traditional power structures by flipping the conventional hierarchy of governance. At its core, it involves a deliberate shift in authority, often placing those typically marginalized or underrepresented at the forefront of decision-making processes. This idea is not merely a modern invention but has roots in historical movements that sought to disrupt established norms. For instance, the Paris Commune of 1871 serves as an early example, where workers and ordinary citizens briefly seized control of the city, experimenting with self-governance and collective leadership. This event, though short-lived, laid the groundwork for later theories on political inversion by demonstrating the potential for alternative power arrangements.

Analyzing the origins of political inversion reveals a recurring theme: resistance to centralized authority. In the 20th century, movements like the Zapatista uprising in Mexico (1994) exemplified this by advocating for indigenous autonomy and grassroots democracy. The Zapatistas inverted traditional governance by prioritizing local communities’ needs over federal dictates, creating a model that resonated globally. Similarly, the Occupy Movement (2011) employed horizontal decision-making structures, rejecting hierarchical leadership to emphasize collective voice. These examples illustrate how political inversion often emerges as a response to perceived injustices, offering a radical reimagining of who holds power and how it is exercised.

The core concept of political inversion in governance hinges on decentralization and inclusivity. It challenges the notion that power must flow from the top down, instead advocating for systems where authority is distributed among diverse groups. This approach is not without challenges; maintaining cohesion and efficiency in decentralized models can be difficult. However, proponents argue that it fosters greater equity and responsiveness to local needs. For instance, participatory budgeting, a practice adopted in cities like Porto Alegre, Brazil, allows citizens to directly decide how public funds are allocated, embodying the principles of political inversion by giving ordinary people a direct say in governance.

To implement political inversion effectively, certain steps are crucial. First, identify the marginalized or underrepresented groups within a given context and ensure their active participation in decision-making processes. Second, establish mechanisms for horizontal communication and consensus-building, such as assemblies or councils. Third, create safeguards to prevent the re-emergence of hierarchical structures, such as term limits or rotating leadership roles. Caution must be taken to avoid tokenism, ensuring that inclusion is meaningful and not merely symbolic. Finally, measure success not by traditional metrics of efficiency but by the degree of empowerment and equity achieved. When executed thoughtfully, political inversion can transform governance into a more just and participatory endeavor.

Do Political Maps Include Road Networks? A Cartographic Exploration

You may want to see also

Mechanisms of Inversion: How power structures are flipped or subverted in politics

Power structures are not immutable; they can be flipped, subverted, or inverted through deliberate mechanisms that exploit vulnerabilities or leverage new tools. One such mechanism is narrative inversion, where dominant ideologies are reframed to expose contradictions or injustices. For instance, during the Civil Rights Movement, activists inverted the narrative of "law and order" by highlighting how segregation laws themselves were unjust, turning a tool of oppression into a symbol of moral hypocrisy. This tactic shifts public perception by revealing the power structure’s reliance on flawed or self-serving logic.

Another mechanism is institutional co-optation, where existing systems are infiltrated and repurposed from within. A practical example is the use of parliamentary procedure by marginalized groups to block or delay oppressive legislation. In the 1990s, the Texas House Democrats employed a quorum-busting strategy to prevent a redistricting vote, effectively subverting the majority’s power by exploiting procedural rules. This approach requires a deep understanding of institutional mechanics and the discipline to act within—yet against—the system.

Technological disruption also plays a critical role in inversion. Social media platforms have democratized information dissemination, allowing grassroots movements to bypass traditional gatekeepers. During the Arab Spring, activists used Twitter and Facebook to organize protests and share uncensored information, undermining state-controlled media. However, caution is necessary: over-reliance on technology can expose movements to surveillance or misinformation campaigns. A balanced strategy involves using tech tools while maintaining offline networks for resilience.

Finally, symbolic inversion leverages cultural or historical symbols to challenge authority. The 2020 Black Lives Matter protests repurposed the American flag as a backdrop for demands for racial justice, reclaiming a symbol often associated with nationalism. This tactic works by forcing a reevaluation of shared values, exposing the gap between idealized narratives and lived realities. For maximum impact, symbols should be chosen carefully to resonate with both the movement’s base and the broader public.

Inversion is not a one-size-fits-all strategy; it requires adaptability and a clear understanding of context. Whether through narrative, institutional, technological, or symbolic means, the goal is to expose and dismantle power asymmetries. Practitioners must remain vigilant against co-optation or backlash, ensuring that inverted structures do not simply reproduce old hierarchies in new forms. Mastery of these mechanisms offers a playbook for those seeking to challenge entrenched power—but success depends on precision, timing, and a commitment to transformative change.

Putin's Political Slogans: Decoding His Rhetoric and Public Messaging

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: Case studies of political inversion in different societies

Political inversion, where the oppressed become the oppressors or the marginalized seize power only to replicate the systems they once fought against, is a recurring theme in history. The French Revolution offers a stark example. Initially, the Revolution overthrew the monarchy, promising liberty, equality, and fraternity. However, it quickly devolved into the Reign of Terror, where the revolutionary leaders, once victims of tyranny, employed the same brutal tactics against perceived enemies. Robespierre’s Committee of Public Safety executed thousands, illustrating how the pursuit of ideological purity can mirror the very oppression it sought to dismantle. This case underscores the danger of unchecked power, even in the hands of those who claim to fight for justice.

In contrast, the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia presents a more structured yet equally instructive inversion. Lenin and his comrades overthrew the Tsarist autocracy, vowing to establish a classless society. Yet, under Stalin, the Soviet Union became a totalitarian regime characterized by mass surveillance, purges, and forced labor camps. The proletariat, once the supposed beneficiaries of the revolution, were subjugated by a new elite. This inversion highlights how revolutionary ideals can be corrupted by the mechanisms of state control, transforming liberators into tyrants. The takeaway here is that institutional power, without accountability, often perpetuates the very hierarchies it aims to destroy.

A less violent but equally revealing example is the post-apartheid government in South Africa. After decades of struggle against racial segregation, the African National Congress (ANC) took power in 1994, promising equality and justice. However, corruption, economic inequality, and political cronyism have marred its legacy. The ANC, once a symbol of resistance, now faces accusations of exploiting state resources for personal gain. This inversion demonstrates how historical victimhood does not guarantee moral governance. It serves as a cautionary tale: dismantling oppressive structures requires not only political change but also a commitment to transparency and accountability.

Finally, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 provides a religious dimension to political inversion. Overthrowing the Shah’s secular dictatorship, the revolution established an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Khomeini. Initially, it was hailed as a triumph of popular will against imperialism. Yet, the new regime imposed strict religious laws, suppressed dissent, and marginalized women and minorities. The revolutionaries, once oppressed by the Shah’s regime, became enforcers of a different kind of tyranny. This case reveals how ideological rigidity can lead to inversion, where the fight for freedom results in new forms of oppression. It reminds us that the means of achieving power often dictate its ends.

These historical examples illustrate that political inversion is not merely a theoretical concept but a recurring pattern in societies undergoing radical change. Whether through violence, institutional corruption, or ideological zeal, the oppressed can become oppressors when power is wielded without restraint. The key takeaway is that true transformation requires more than overthrowing existing systems—it demands a sustained commitment to the principles of justice, equality, and accountability. Otherwise, the cycle of inversion persists, perpetuating suffering under new banners.

Louis Farrakhan's Political Influence: Activism, Controversy, and Legacy Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Causes and Triggers: Factors leading to the emergence of political inversion

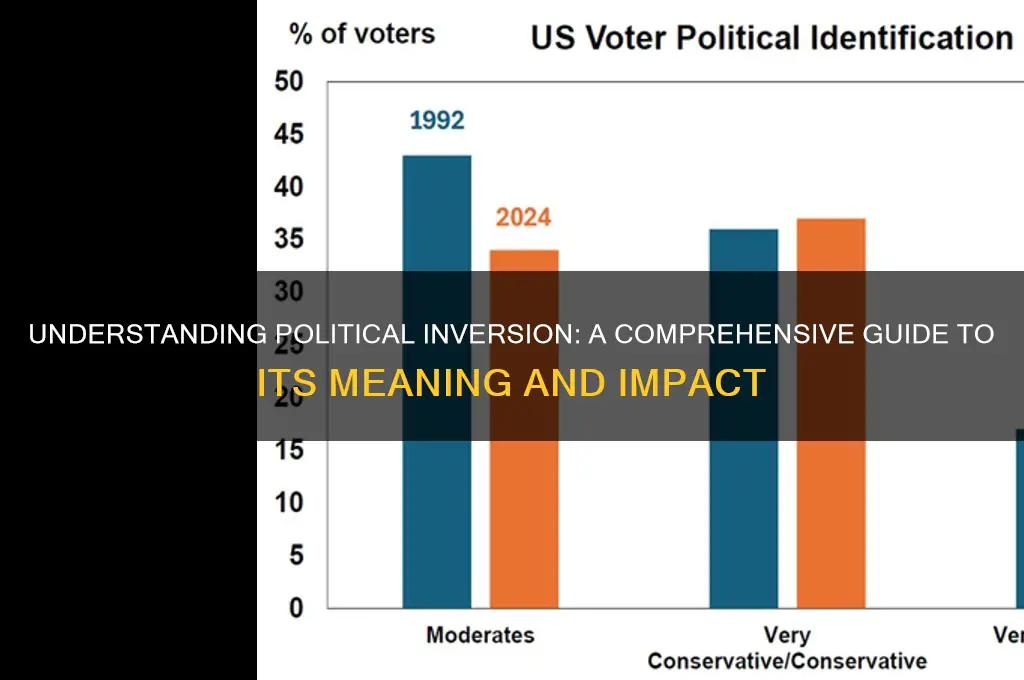

Political inversion, where fringe or extremist ideologies gain mainstream traction, often emerges from a toxic interplay of systemic failures and individual vulnerabilities. Economic disenfranchisement acts as a primary catalyst, pushing individuals towards narratives that promise radical solutions to their material struggles. When traditional institutions fail to address income inequality, job insecurity, or social mobility, the allure of populist or extremist movements grows. For instance, the rise of far-right parties in post-2008 Europe correlated with regions hardest hit by austerity measures, illustrating how economic despair can fertilize the ground for inversion.

Another critical trigger lies in the erosion of trust in established institutions, a phenomenon exacerbated by corruption scandals, bureaucratic inefficiency, or perceived elitism. When governments, media outlets, or international bodies are seen as serving narrow interests rather than the public good, citizens become susceptible to alternative narratives that frame these institutions as the enemy. Social media amplifies this dynamic, creating echo chambers where distrust festers and radical ideas spread unchecked. The 2016 U.S. election, marked by widespread disillusionment with both major parties, exemplifies how institutional distrust can fuel political inversion.

Cultural displacement and identity anxiety also play pivotal roles, particularly in societies undergoing rapid demographic or social change. When individuals feel their cultural heritage or way of life is under threat, they may gravitate toward ideologies that promise restoration or protection. Immigration, globalization, and progressive social movements often become scapegoats in such narratives. For example, the Brexit campaign’s emphasis on "taking back control" tapped into anxieties about national identity and sovereignty, demonstrating how cultural insecurities can trigger inversion.

Finally, the manipulation of information and the weaponization of discourse cannot be overlooked. Political inversion thrives in environments where facts are contested, and truth becomes relative. Disinformation campaigns, whether state-sponsored or grassroots, exploit cognitive biases and emotional triggers to sow division and normalize extremism. The QAnon phenomenon, which gained traction through conspiracy theories spread online, highlights how information warfare can create fertile ground for inversion. Countering this requires not only media literacy but also systemic efforts to restore the integrity of public discourse.

Tribes: Cultural Identities or Political Entities? Exploring the Dual Nature

You may want to see also

Consequences and Impact: Effects of political inversion on stability and governance

Political inversion, where traditional power dynamics are flipped or subverted, often leads to profound consequences for stability and governance. One immediate effect is the erosion of institutional trust. When political norms are inverted—such as when populist leaders undermine established institutions or when minority groups suddenly gain disproportionate influence—citizens may question the legitimacy of governance structures. For instance, in countries where populist movements have risen to power by rejecting elite-driven policies, public confidence in judiciary systems or electoral processes can plummet. This distrust creates a feedback loop: weakened institutions struggle to enforce laws or deliver services effectively, further alienating the population.

Consider the practical implications for policymakers. Inverted political landscapes demand adaptive strategies. For example, governments facing sudden shifts in power dynamics—like a youth-led movement overturning long-standing policies—must engage in rapid stakeholder mapping. Identify key influencers, even if they operate outside traditional power structures, and establish dialogue channels. A step-by-step approach could include: 1) Conducting social media sentiment analysis to gauge public mood, 2) Organizing town hall meetings in both urban and rural areas, and 3) Co-creating policy frameworks with emergent leaders. Caution: Avoid tokenism; genuine inclusion requires ceding some decision-making authority.

From a comparative perspective, the impact of political inversion varies by context. In democracies with strong civil society, inverted power dynamics—such as grassroots movements challenging corporate influence—can lead to progressive reforms. Conversely, in authoritarian regimes, inversion often results in instability. For instance, the Arab Spring inverted traditional power hierarchies but led to prolonged conflict in some nations due to the absence of democratic institutions to manage the transition. The takeaway: The consequences of inversion depend on the resilience of existing governance frameworks. Democracies with robust checks and balances are better equipped to absorb shocks, while fragile states risk descent into chaos.

Descriptively, the aftermath of political inversion often resembles a political earthquake, with aftershocks felt across sectors. Economic stability is particularly vulnerable. Investors shy away from uncertainty, leading to capital flight and currency devaluation. For example, in countries where inversion results in abrupt policy reversals—like nationalizing industries previously privatized—foreign direct investment can drop by as much as 30% within a year. Socially, inversion can exacerbate polarization. When one group’s sudden ascendancy is perceived as another’s marginalization, protests, or even violence, may ensue. Practical tip: Governments should establish early warning systems to monitor economic indicators and social media trends, allowing for preemptive intervention.

Persuasively, the long-term impact of political inversion hinges on leadership response. Inverted dynamics present an opportunity for transformative governance if managed proactively. Leaders who embrace inversion as a call for systemic reform—rather than a threat to be suppressed—can foster greater inclusivity and innovation. For instance, Estonia’s digital governance model emerged from a post-Soviet inversion, leveraging technology to rebuild trust and efficiency. Conversely, leaders who resist change risk deepening divisions. The choice is clear: Adapt to inversion’s challenges, or succumb to its destabilizing forces.

Politics vs. Morality: Navigating the Complex Intersection of Power and Ethics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political inversion refers to a situation where the traditional roles or positions of political parties, ideologies, or policies are reversed or flipped, often leading to unexpected alliances, shifts in power, or changes in public perception.

Political inversion can occur due to societal changes, economic shifts, crises, or strategic maneuvering by political actors. It often arises when established norms or expectations are challenged, forcing a reconfiguration of political landscapes.

Examples include left-wing parties adopting traditionally right-wing policies (e.g., austerity measures) or right-wing parties embracing progressive issues (e.g., environmental policies). Another example is when populist movements challenge the establishment from both sides of the political spectrum.

Political inversion can lead to confusion among voters, realignment of political coalitions, and the emergence of new political narratives. It may also destabilize traditional party systems or create opportunities for new movements to gain influence.