Political instability refers to a state of uncertainty, turmoil, or frequent changes within a country's political system, often characterized by weak governance, conflicts among political factions, or a lack of public trust in institutions. It can arise from various factors, including economic crises, social unrest, corruption, or power struggles, and typically manifests as frequent leadership changes, policy inconsistencies, or even violence. Understanding its definition is crucial, as it directly impacts a nation's development, security, and the well-being of its citizens, often leading to economic decline, reduced foreign investment, and diminished international credibility.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political instability refers to a state of uncertainty, disorder, or frequent changes in a country's political system, often marked by conflicts, instability in governance, or threats to the continuity of the regime. |

| Key Indicators | Frequent changes in government, coups, civil unrest, protests, and elections disputes. |

| Causes | Economic inequality, corruption, ethnic or religious divisions, weak institutions, external interference, and authoritarian rule. |

| Economic Impact | Reduced foreign investment, economic stagnation, inflation, and decreased GDP growth. |

| Social Impact | Increased crime rates, displacement of populations, human rights violations, and erosion of public trust in government. |

| Global Implications | Regional conflicts, refugee crises, and potential intervention by international bodies or neighboring countries. |

| Measurement Tools | Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism Index (World Bank), Fragile States Index (Fund for Peace). |

| Examples | Recent cases include Venezuela, Myanmar, and Afghanistan, where political instability has led to significant social and economic crises. |

| Mitigation Strategies | Strengthening democratic institutions, promoting transparency, addressing economic disparities, and fostering inclusive governance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Causes of Instability: Economic crises, social inequality, corruption, weak institutions, and leadership conflicts

- Types of Instability: Political violence, regime change, protests, coups, and electoral disputes

- Effects on Society: Economic decline, human rights violations, migration, and social fragmentation

- Measuring Instability: Indicators like conflict frequency, governance quality, and public trust

- Global Examples: Historical and contemporary cases of political instability worldwide

Causes of Instability: Economic crises, social inequality, corruption, weak institutions, and leadership conflicts

Economic crises often serve as the spark that ignites political instability, but their impact is rarely isolated. Consider the 2008 global financial crisis, which triggered protests and regime changes in countries like Iceland and Greece. When economies collapse, unemployment soars, and public services deteriorate, citizens lose faith in their governments. This erosion of trust is compounded when austerity measures disproportionately burden the poor, widening the gap between the haves and have-nots. Economic downturns don’t just destabilize markets; they destabilize societies by creating fertile ground for discontent and radicalization.

Social inequality acts as a slow-burning fuse for political upheaval, often intersecting with economic crises. In South Africa, for instance, the legacy of apartheid continues to fuel protests over land rights and economic opportunities. When marginalized groups perceive systemic barriers to their advancement, frustration festers. This isn’t merely about income disparities; it’s about access to education, healthcare, and political representation. Governments that fail to address these inequalities risk alienating large segments of their population, turning social divisions into political fault lines.

Corruption corrodes the foundations of stability by undermining public trust and diverting resources from critical services. Take Nigeria, where billions in oil revenues have disappeared into private pockets, leaving infrastructure crumbling and citizens impoverished. Corruption doesn’t just steal money; it steals hope. When leaders prioritize personal gain over public welfare, citizens feel betrayed, and protests like the End SARS movement in Nigeria become inevitable. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index consistently shows that countries with high corruption levels are more prone to political unrest, proving that integrity isn’t just a moral issue—it’s a matter of survival for governments.

Weak institutions are the Achilles’ heel of any political system, unable to withstand the pressures of crises or public discontent. In Venezuela, the collapse of democratic checks and balances under Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro paved the way for authoritarianism and economic ruin. Institutions like an independent judiciary, free press, and accountable law enforcement aren’t luxuries; they’re essential safeguards against abuse of power. Without them, leadership conflicts escalate into power grabs, and citizens lose faith in the system itself. Strengthening institutions isn’t just about writing laws—it’s about ensuring they’re enforced, even when it’s inconvenient for those in power.

Leadership conflicts, whether within ruling parties or between rival factions, create vacuums that instability rushes to fill. Zimbabwe’s post-Mugabe era exemplifies this, as internal power struggles within ZANU-PF hindered economic recovery and deepened public disillusionment. When leaders prioritize personal or factional interests over national stability, the result is policy paralysis and public distrust. Resolving such conflicts requires more than just mediation; it demands a commitment to inclusive governance and a willingness to prioritize the common good over personal ambition. Without this, even the most resource-rich nations can descend into chaos.

Understanding Political Features: Key Elements Shaping Governance and Society

You may want to see also

Types of Instability: Political violence, regime change, protests, coups, and electoral disputes

Political instability manifests in various forms, each with distinct triggers, dynamics, and consequences. Among the most visible and disruptive types are political violence, regime change, protests, coups, and electoral disputes. These phenomena often intertwine, creating a complex web of instability that challenges governance and societal cohesion. Understanding their nuances is essential for diagnosing and addressing the root causes of turmoil.

Political violence is perhaps the most visceral expression of instability, ranging from isolated assassinations to widespread civil conflict. It often arises from deep-seated grievances, such as economic inequality, ethnic tensions, or ideological polarization. For instance, the Rwandan genocide of 1994 was fueled by decades of ethnic divisions exacerbated by political manipulation. Analyzing political violence requires examining its structural causes, immediate triggers, and the role of external actors. Mitigating it demands not only security responses but also long-term strategies to address underlying injustices and foster inclusive institutions.

Regime change can occur through democratic transitions, revolutions, or external interventions, each with different implications for stability. Democratic transitions, like those seen in Eastern Europe post-1989, often involve negotiated settlements and institutional reforms, fostering legitimacy. In contrast, revolutions, such as the Arab Spring, can lead to power vacuums and prolonged instability if new leadership fails to consolidate authority. External interventions, as in Iraq in 2003, frequently disrupt social fabric and sow seeds of future conflict. The takeaway is that the process of regime change matters as much as its outcome in determining stability.

Protests are a common precursor to or symptom of instability, serving as a barometer of public discontent. They can be peaceful, like the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement, or escalate into violent clashes, as seen in France’s Yellow Vests protests. Governments often face a dilemma: suppress protests and risk further alienation, or accommodate demands and risk appearing weak. Effective management involves addressing protester grievances through dialogue and policy reforms while maintaining public order. Ignoring these signals can lead to more severe forms of instability, such as coups or civil unrest.

Coups represent abrupt and often violent seizures of power, typically by military factions dissatisfied with existing leadership. Recent examples include Mali in 2020 and Myanmar in 2021. Coups destabilize nations by undermining democratic norms, eroding trust in institutions, and often triggering international sanctions. They are frequently driven by internal power struggles, economic crises, or perceived leadership failures. Preventing coups requires strengthening civilian oversight of the military, ensuring economic stability, and fostering a culture of democratic accountability.

Electoral disputes arise when election results are contested, often due to allegations of fraud, irregularities, or lack of transparency. Kenya’s 2007 elections and the 2020 U.S. presidential contest highlight how such disputes can escalate into violence or constitutional crises. Resolving electoral disputes requires robust judicial systems, independent electoral bodies, and international mediation when necessary. The key is to ensure that all parties accept the legitimacy of the process, even if they disagree with the outcome. Without this, elections can become catalysts for instability rather than tools for democratic renewal.

In conclusion, political instability is not a monolithic phenomenon but a spectrum of challenges, each requiring tailored responses. By dissecting its types—political violence, regime change, protests, coups, and electoral disputes—policymakers, scholars, and citizens can better navigate the complexities of governance and work toward sustainable solutions.

Understanding Political Rallies: Strategies, Impact, and Public Engagement Explained

You may want to see also

Effects on Society: Economic decline, human rights violations, migration, and social fragmentation

Political instability, often defined as the inability of a government to maintain order, enforce laws, or provide basic services, triggers a cascade of societal effects. Among these, economic decline stands out as both a symptom and a driver of further turmoil. When political uncertainty reigns, investors withdraw, businesses shutter, and unemployment soars. For instance, in countries like Venezuela, prolonged political instability has led to hyperinflation, collapsing industries, and a GDP contraction exceeding 80% since 2013. Such economic freefall disproportionately affects the vulnerable—low-income families, small businesses, and informal workers—who lack the resources to weather the storm. The takeaway? Economic decline is not merely a financial crisis but a societal one, eroding livelihoods and deepening inequality.

Human rights violations flourish in the shadow of political instability, as weakened or authoritarian regimes exploit the chaos to consolidate power. Torture, arbitrary arrests, and censorship become tools of control, often targeting dissenters, minorities, and journalists. Consider Myanmar, where the 2021 military coup unleashed a wave of violence against civilians, with over 1,000 deaths reported in the first year alone. International accountability mechanisms often falter in such contexts, leaving victims with little recourse. Practical tip: Support local and international organizations documenting abuses, as evidence-gathering can pave the way for future justice. The lesson here is clear—political instability creates fertile ground for systemic rights abuses, demanding global vigilance and action.

Migration emerges as both a consequence and a coping mechanism in politically unstable regions. As economies collapse and violence escalates, millions flee in search of safety and opportunity. Syria’s decade-long conflict, for example, has displaced over 13 million people, with refugees straining resources in host countries like Lebanon and Jordan. Yet, migration is not without risks; perilous journeys, exploitation, and xenophobic backlash await many. For those considering humanitarian aid, focus on sustainable solutions like education for refugee children and job training programs, which empower displaced populations to rebuild their lives. Migration, in this context, is not just a crisis but a testament to human resilience—and a call for compassionate, long-term responses.

Social fragmentation is the silent yet profound consequence of political instability, tearing at the fabric of communities. As trust in institutions wanes, ethnic, religious, or regional divisions deepen, often fueled by political manipulation. In Iraq, post-invasion instability exacerbated sectarian tensions, leading to cycles of violence and displacement. To combat fragmentation, invest in grassroots initiatives that foster dialogue and cooperation across divides. For instance, intergroup contact theory suggests that structured interactions between divided groups can reduce prejudice. Caution: Avoid tokenistic efforts; meaningful reconciliation requires sustained commitment and inclusive leadership. Ultimately, social fragmentation is not inevitable—it can be countered through deliberate, community-driven efforts to rebuild trust and unity.

Female Voices on AM Radio: Shaping Political Discourse and Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Measuring Instability: Indicators like conflict frequency, governance quality, and public trust

Political instability is a complex phenomenon, often marked by frequent conflicts, eroding governance, and dwindling public trust. To measure it effectively, analysts rely on specific indicators that capture its multifaceted nature. Conflict frequency stands as a primary metric, quantifying the number and intensity of violent or non-violent disputes within a political system. For instance, countries experiencing recurring protests, coups, or civil wars score higher on instability scales. However, raw numbers alone are insufficient; context matters. A single high-intensity conflict can destabilize a nation more than multiple low-intensity skirmishes.

Beyond conflict, governance quality serves as another critical indicator. This encompasses factors like corruption levels, rule of law, and bureaucratic efficiency. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) provides a standardized framework, scoring countries on a scale of -2.5 to 2.5. A nation with a score below -1.0 in areas like "control of corruption" or "government effectiveness" is often flagged as politically unstable. For example, Zimbabwe’s governance scores have consistently hovered around -1.5, reflecting systemic issues that fuel instability.

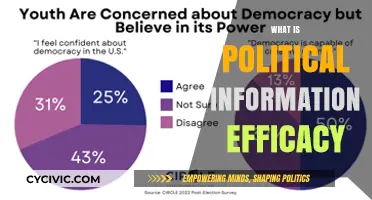

Public trust in institutions acts as a barometer of political health. Surveys like the Edelman Trust Barometer measure citizen confidence in government, media, and NGOs. A trust deficit below 40% often correlates with instability, as seen in countries like Venezuela or Lebanon. Practical tips for policymakers include conducting regular trust audits and addressing grievances transparently to rebuild confidence.

Comparatively, while conflict frequency and governance quality are objective, public trust is subjective and culturally nuanced. For instance, trust thresholds vary; Nordic countries maintain stability with trust levels above 70%, whereas some Asian nations remain stable with trust around 50%. This highlights the need for localized benchmarks when measuring instability.

In conclusion, measuring political instability requires a triangulated approach. By combining conflict frequency, governance quality, and public trust, analysts can paint a comprehensive picture. Caution must be exercised to avoid oversimplification, as instability is context-dependent. Policymakers should prioritize actionable insights, such as reducing corruption, mediating conflicts, and fostering inclusive governance, to mitigate instability effectively.

Are Political Ads Protected Speech? Exploring Free Speech Limits

You may want to see also

Global Examples: Historical and contemporary cases of political instability worldwide

Political instability manifests in various forms, from coups and civil wars to economic collapse and social unrest. Examining global examples reveals recurring patterns and triggers, offering insights into its causes and consequences.

Historical Case Study: The Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Germany’s Weimar Republic exemplifies how economic crisis and political polarization breed instability. Hyperinflation, fueled by war reparations and fiscal mismanagement, eroded public trust in institutions. Extremist groups like the Nazis exploited widespread discontent, leading to political violence and the eventual collapse of democracy. This case underscores the fragility of young democracies when economic and social pressures converge.

Contemporary Example: Venezuela (2010s–Present)

Venezuela’s crisis combines authoritarianism, economic mismanagement, and resource dependency. The collapse of oil prices in 2014 exacerbated existing issues, leading to hyperinflation, food shortages, and mass migration. President Nicolás Maduro’s consolidation of power, coupled with allegations of election fraud, deepened political divisions. This scenario highlights how resource-dependent economies and authoritarian regimes can spiral into prolonged instability.

Comparative Analysis: Arab Spring (2010–2012) vs. Sudan (2019)

The Arab Spring and Sudan’s 2019 revolution share roots in public grievances over corruption, unemployment, and authoritarian rule. However, outcomes diverged sharply. Tunisia transitioned to democracy, while Libya and Syria descended into civil war. Sudan’s revolution led to a fragile power-sharing agreement, illustrating how institutional strength and external interventions shape post-uprising trajectories.

Practical Takeaway: Early Warning Signs and Mitigation

Identifying early indicators of instability—such as rising inequality, erosion of press freedom, or frequent protests—is crucial. Governments and international bodies can mitigate risks through economic diversification, inclusive governance, and dialogue. For instance, Tunisia’s post-Arab Spring success was partly due to civil society engagement and international support. Proactive measures, tailored to local contexts, can prevent escalation into full-blown crises.

Exploring the Proliferation of Political Facebook Pages Online

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political instability refers to a situation in which a country or government experiences frequent changes, disruptions, or uncertainties in its political system, often marked by conflicts, protests, or leadership crises.

Political instability can be caused by factors such as economic inequality, corruption, ethnic or religious divisions, weak institutions, external interference, or contested elections.

Political instability often leads to economic uncertainty, reduced foreign investment, decreased tourism, currency devaluation, and hindered long-term development due to a lack of policy continuity.

Political instability can be resolved through measures like democratic reforms, inclusive governance, addressing root causes of conflict, strengthening institutions, and fostering dialogue among opposing factions.