The political ideology quadrant is a widely used framework for mapping and understanding the diverse spectrum of political beliefs. Typically represented as a two-dimensional graph, it categorizes ideologies based on their stances regarding individual liberty versus collective authority (often labeled as the left-right axis) and social freedom versus economic regulation (often labeled as the authoritarian-libertarian axis). This model helps to visualize how different political philosophies, such as liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and libertarianism, relate to one another, offering a simplified yet insightful tool for analyzing political discourse and identifying areas of agreement or conflict among various ideologies.

Explore related products

$50.03 $62.99

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Explains the concept and historical roots of the political ideology quadrant

- Four Quadrants Overview: Describes the four main quadrants: authoritarian, libertarian, left, and right

- Key Characteristics: Highlights core beliefs and values associated with each quadrant

- Modern Applications: Discusses how the quadrant model is used in contemporary politics

- Criticisms and Limitations: Examines flaws and debates surrounding the quadrant system

Definition and Origins: Explains the concept and historical roots of the political ideology quadrant

The political ideology quadrant is a visual tool that simplifies the complex spectrum of political beliefs into a two-dimensional grid. Typically, it plots ideologies along two axes: economic (left to right, representing degrees of government intervention in the economy) and social (authoritarian to libertarian, reflecting attitudes toward personal freedoms). This framework emerged as a way to categorize and compare diverse political philosophies, making abstract ideas more accessible. While its exact origins are debated, its roots can be traced to early 20th-century political theory, where thinkers sought to map the ideological landscape amid rising socialism, fascism, and liberalism.

Analytically, the quadrant’s structure reflects a fundamental tension in political thought: the balance between individual liberty and collective welfare. The vertical axis, often labeled "social," distinguishes between authoritarian views, which prioritize order and hierarchy, and libertarian views, which emphasize personal autonomy. The horizontal axis, labeled "economic," separates left-wing ideologies favoring redistribution and regulation from right-wing ideologies advocating free markets and limited government. This dual-axis system allows for nuanced distinctions, such as how a socially libertarian but economically left-leaning ideology (e.g., social democracy) differs from a socially authoritarian but economically right-leaning one (e.g., fascism).

Instructively, understanding the quadrant’s origins requires examining its intellectual precursors. The 19th-century distinction between "left" and "right" emerged during the French Revolution, with supporters of tradition sitting to the right of proponents of radical change. However, this single-axis model proved insufficient as ideologies diversified. The addition of a second axis gained traction in the mid-20th century, particularly through the work of political scientists like Ronald Inglehart, who emphasized the importance of cultural values in shaping political attitudes. This evolution transformed the linear spectrum into a multidimensional grid, better capturing the complexity of modern politics.

Persuasively, the quadrant’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to foster dialogue across ideological divides. By visualizing beliefs as points on a grid rather than rigid categories, it encourages users to consider the interplay between economic and social values. For instance, it highlights how a libertarian’s emphasis on individual freedom can align with both free-market capitalism and progressive social policies, challenging simplistic stereotypes. This framework also serves as a diagnostic tool, helping individuals identify their own beliefs and understand those of others, thereby promoting informed political engagement.

Comparatively, while the quadrant is widely used, it is not without limitations. Critics argue that it oversimplifies ideologies, reducing them to coordinates on a graph. For example, it struggles to account for hybrid or evolving ideologies, such as eco-socialism or national conservatism, which blend elements from multiple quadrants. Additionally, its Western-centric origins may limit its applicability to non-Western political contexts, where different historical and cultural factors shape ideological frameworks. Despite these shortcomings, the quadrant remains a valuable starting point for exploring the rich tapestry of political thought.

Understanding Wisconsin State Politics: A Comprehensive Guide to the Process

You may want to see also

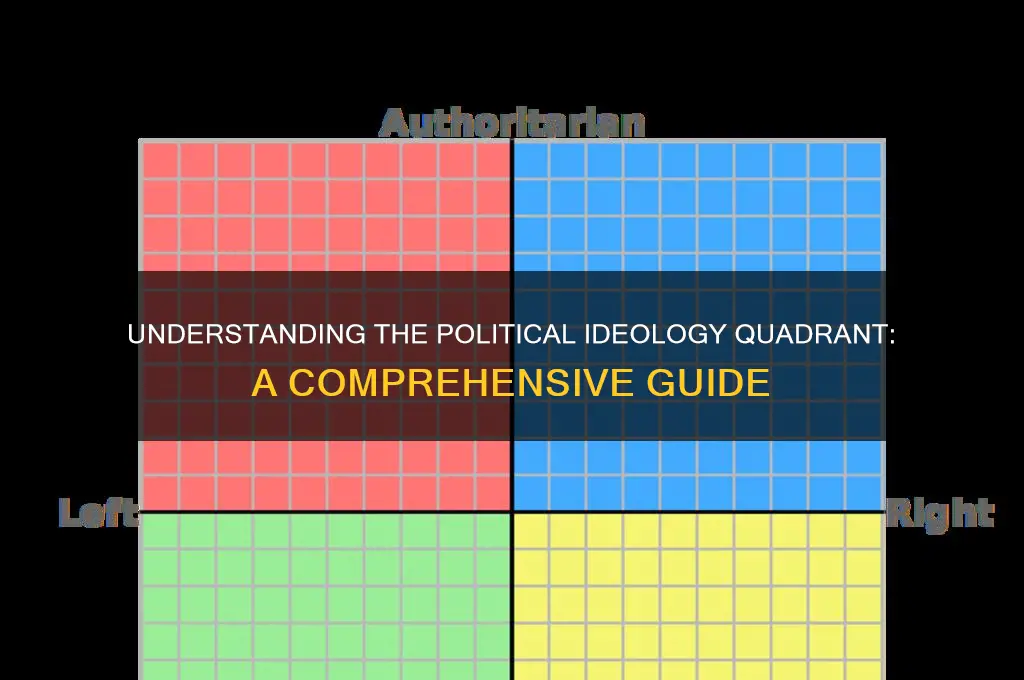

Four Quadrants Overview: Describes the four main quadrants: authoritarian, libertarian, left, and right

Political ideology quadrants simplify complex beliefs into a visual framework, mapping four primary positions: authoritarian, libertarian, left, and right. Each quadrant represents a distinct approach to governance, individual freedoms, and economic systems. Understanding these quadrants helps clarify political debates and aligns individuals with ideologies that resonate with their values.

Authoritarianism prioritizes order and stability above individual freedoms. Governments in this quadrant wield significant control over citizens’ lives, often justifying their power through appeals to tradition, national unity, or security. Examples include historical regimes like Nazi Germany and modern states with strict censorship laws. While authoritarianism can enforce rapid decision-making, it risks suppressing dissent and stifling innovation. For instance, countries with high authoritarian scores on the Democracy Index often exhibit lower press freedom and civil liberties.

Libertarianism champions individual liberty as the highest value, advocating minimal government intervention in personal and economic affairs. Libertarians argue that free markets and personal responsibility lead to prosperity and innovation. This quadrant includes classical liberals and anarcho-capitalists, who oppose regulations like mandatory taxes or strict laws. However, critics argue that unchecked libertarianism can exacerbate inequality and neglect public welfare. A practical example is the debate over healthcare: libertarians often oppose government-run systems, favoring private solutions instead.

The left quadrant emphasizes equality and collective welfare, often through progressive taxation, social safety nets, and government intervention to reduce disparities. Leftist ideologies range from social democracy to socialism, focusing on redistributing resources to ensure fairness. For instance, Nordic countries like Sweden combine high taxes with robust public services, achieving lower income inequality. However, detractors argue that excessive redistribution can disincentivize productivity and burden economies.

The right quadrant values tradition, hierarchy, and free markets, often advocating for limited government in economic affairs while promoting conservative social policies. Right-wing ideologies prioritize individual achievement and national identity, sometimes at the expense of marginalized groups. For example, conservative parties often support lower taxes and deregulation to stimulate economic growth. Yet, this approach can widen wealth gaps and neglect systemic inequalities.

In practice, individuals rarely fit neatly into one quadrant, as political beliefs are nuanced. However, this framework serves as a starting point for understanding ideological differences. By examining these quadrants, one can better navigate political discourse, identify areas of agreement or conflict, and make informed decisions in civic engagement.

Mastering Polite Follow-Ups: Tips for Professional and Effective Communication

You may want to see also

Key Characteristics: Highlights core beliefs and values associated with each quadrant

The political ideology quadrant, often visualized as a two-dimensional graph, categorizes political beliefs based on two primary axes: economic and social. Each quadrant represents a distinct set of core beliefs and values, offering a simplified yet insightful framework for understanding political diversity. Let’s dissect the key characteristics of each quadrant, highlighting what defines them and how they shape political discourse.

Top-Left Quadrant (Authoritarian Left): This quadrant emphasizes collective welfare and economic equality but often advocates for centralized control to achieve these goals. Core beliefs include strong state intervention in the economy, wealth redistribution, and prioritization of group identity over individualism. Examples include socialist regimes that enforce strict regulations on private enterprise while promoting social safety nets. The takeaway here is that equality is pursued through authority, often at the expense of personal freedoms. For instance, policies like universal healthcare are paired with limited economic autonomy, illustrating the tension between equity and liberty.

Top-Right Quadrant (Authoritarian Right): Here, the focus shifts to preserving traditional hierarchies, national identity, and law and order, often through strong leadership and centralized power. Core values include nationalism, social conservatism, and economic protectionism. Think of policies that prioritize border security, cultural homogeneity, and state-backed industries. This quadrant’s strength lies in its ability to provide stability and order, but it often comes with restrictions on dissent and minority rights. A practical example is the implementation of strict immigration policies alongside subsidies for domestic industries, reflecting a dual emphasis on cultural and economic control.

Bottom-Left Quadrant (Libertarian Left): This quadrant champions individual freedom within a framework of economic and social equality, often advocating for decentralized systems like cooperatives and voluntary associations. Core beliefs include worker ownership, grassroots democracy, and social liberalism. Anarcho-syndicalism is a prime example, where labor unions manage production without state interference. The challenge here is balancing individual autonomy with collective responsibility, as seen in efforts to create community-driven healthcare systems. This quadrant appeals to those seeking equity without authoritarian structures, though scalability remains a practical hurdle.

Bottom-Right Quadrant (Libertarian Right): Freedom reigns supreme here, both economically and socially, with minimal government intervention as the guiding principle. Core values include free markets, personal responsibility, and civil liberties. Think of policies like deregulation, tax cuts, and opposition to government welfare programs. This quadrant thrives on innovation and individual initiative but often struggles with inequality and social safety nets. For instance, a hands-off approach to healthcare can lead to market-driven solutions but may leave vulnerable populations underserved. The key takeaway is that liberty is prioritized, even if it means accepting disparities as a byproduct of free choice.

Understanding these quadrants requires recognizing their trade-offs. Each quadrant offers a unique blend of economic and social principles, but none is without its limitations. By examining their core beliefs and values, we can better navigate political debates and identify where our own priorities align—or clash—with these ideological frameworks. Whether you lean toward collective welfare, individual freedom, traditional order, or market dynamism, the quadrant system provides a lens to explore these tensions and make informed choices.

Understanding Political Ideology: Core Beliefs, Impact, and Global Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$5.99 $6.99

Modern Applications: Discusses how the quadrant model is used in contemporary politics

The political ideology quadrant, a model that maps political beliefs onto a two-dimensional grid, has become a cornerstone in contemporary political discourse. Its modern applications are both diverse and impactful, offering a simplified yet effective framework for understanding complex political landscapes. By categorizing ideologies along axes such as economic and social freedom, the quadrant model provides a visual tool that politicians, analysts, and voters use to navigate the increasingly polarized political environment.

One of the most prominent modern applications of the quadrant model is in political campaigns and messaging. Candidates and parties often position themselves within this framework to clarify their stances and differentiate themselves from opponents. For instance, a candidate might emphasize their commitment to economic liberty and social conservatism, placing themselves in the libertarian-right quadrant, while another might advocate for social progressivism and economic equality, aligning with the authoritarian-left quadrant. This strategic use of the model helps voters quickly identify where a candidate stands on key issues, making it easier to align personal beliefs with political choices.

Another critical application is in media and public discourse. News outlets and social media platforms frequently employ the quadrant model to analyze and categorize political movements, parties, and individuals. This usage extends beyond traditional politics, influencing how topics like climate policy, healthcare reform, and technological regulation are discussed. For example, debates on environmental regulations often pit those favoring government intervention (authoritarian-left) against those advocating for market-driven solutions (libertarian-right). By framing these discussions within the quadrant model, media outlets provide audiences with a structured way to understand competing perspectives.

The quadrant model also plays a significant role in academic and policy research. Scholars use it to study political trends, voter behavior, and the evolution of ideologies over time. For instance, research might explore how younger demographics are shifting toward the libertarian-left quadrant, emphasizing both social freedom and economic redistribution. Policymakers, in turn, leverage these insights to craft legislation that resonates with specific ideological groups. This application ensures that political strategies are data-driven and tailored to the diverse beliefs of the electorate.

Despite its utility, the quadrant model is not without limitations. Its simplicity can oversimplify nuanced ideologies, potentially leading to misunderstandings or stereotypes. For example, labeling a political group as strictly authoritarian or libertarian may ignore internal diversity or evolving stances. Users of the model must exercise caution, recognizing its value as a starting point rather than a definitive classification system. When applied thoughtfully, however, the quadrant model remains a powerful tool for making sense of modern politics, fostering informed dialogue, and bridging ideological divides.

Is The Economist Politically Biased? Uncovering Its Editorial Slant

You may want to see also

Criticisms and Limitations: Examines flaws and debates surrounding the quadrant system

The political ideology quadrant, often visualized as a 2x2 grid mapping economic and social dimensions, simplifies complex beliefs into four categories: authoritarian-left, authoritarian-right, libertarian-left, and libertarian-right. While this model offers a starting point for understanding political diversity, it suffers from oversimplification. Reducing multifaceted ideologies to two axes ignores nuances within each quadrant, such as varying degrees of economic intervention or social conservatism. For instance, both a democratic socialist and an anarcho-communist might fall into the libertarian-left quadrant despite fundamentally different approaches to governance and resource distribution.

One of the most glaring limitations of the quadrant system is its inability to account for cross-cutting issues or hybrid ideologies. Real-world political movements often defy neat categorization. Environmentalism, for example, can align with both left-wing and right-wing ideologies, depending on whether it emphasizes collective action or individual responsibility. Similarly, populism transcends traditional economic and social axes, appearing in both authoritarian and libertarian contexts. This rigidity renders the quadrant system inadequate for capturing the fluidity of modern political thought.

Critics also argue that the quadrant model perpetuates false equivalencies by placing ideologies with vastly different historical contexts and implications on the same plane. For instance, authoritarian-left regimes like the Soviet Union and authoritarian-right regimes like Franco’s Spain are often grouped together despite differing motivations, methods, and outcomes. Such comparisons risk trivializing the unique horrors of specific regimes and obscure the moral distinctions between them. This lack of historical sensitivity undermines the model’s utility for serious political analysis.

Finally, the quadrant system often fails to address cultural and regional variations in political ideology. What constitutes “left” or “right” in one country may differ significantly elsewhere. For example, the American left is more centrist by European standards, while social conservatism in India takes on a distinct character compared to its Western counterparts. By imposing a universal framework, the quadrant system risks erasing these contextual differences, leading to misinterpretations of local political dynamics.

In practical terms, relying solely on the quadrant system can hinder constructive political dialogue. Its binary nature encourages polarization, framing politics as a zero-sum game between opposing corners rather than a spectrum of perspectives. To overcome this limitation, consider supplementing the quadrant model with more granular frameworks, such as the Nolan Chart or multidimensional scaling, which allow for greater complexity. Engaging with diverse sources and historical contexts can also provide a more nuanced understanding of political ideologies. Ultimately, while the quadrant system serves as a useful introductory tool, it should not be the final word in political analysis.

Is Hungary Politically Stable? Analyzing Its Current Political Climate

You may want to see also