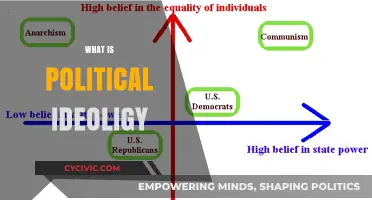

Political ideology refers to a set of beliefs, values, principles, and ideas that guide individuals or groups in understanding and shaping political systems, governance, and societal structures. It serves as a framework for interpreting political events, formulating policies, and advocating for specific goals, such as equality, liberty, or economic prosperity. Ideologies often reflect differing perspectives on the role of government, the distribution of power, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens. Examples include liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and fascism, each offering distinct visions for organizing society. Understanding political ideology is crucial for analyzing political behavior, conflicts, and the evolution of political systems across different cultures and historical contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| System of Beliefs | A set of ideas, principles, and doctrines that guide political thought. |

| Guiding Framework | Provides a framework for understanding and interpreting political events. |

| Normative Orientation | Advocates for specific norms, values, and goals for society. |

| Social Order Vision | Offers a vision of how society should be structured and organized. |

| Policy Advocacy | Informs and justifies specific policies and actions in governance. |

| Identity and Mobilization | Shapes political identities and mobilizes groups around shared beliefs. |

| Historical Context | Often rooted in historical, cultural, or philosophical contexts. |

| Dynamic and Evolving | Adapts over time in response to changing social, economic, and political conditions. |

| Diverse Spectrum | Exists across a spectrum, from left-wing to right-wing and everything in between. |

| Influences Behavior | Shapes the behavior and decisions of individuals, groups, and institutions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Political Ideologies: Historical roots, cultural influences, and key thinkers shaping foundational political beliefs

- Types of Political Ideologies: Liberalism, conservatism, socialism, fascism, and other major ideological frameworks

- Core Principles: Key values, goals, and policies that define and differentiate political ideologies

- Role in Governance: How ideologies influence policy-making, institutions, and societal structures

- Evolution Over Time: Adaptation, decline, and resurgence of ideologies in response to global changes

Origins of Political Ideologies: Historical roots, cultural influences, and key thinkers shaping foundational political beliefs

Political ideologies are not born in a vacuum; they emerge from the fertile soil of history, culture, and the minds of visionary thinkers. Consider the Enlightenment, a period that birthed liberalism. Philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau challenged monarchical absolutism, advocating for individual rights and social contracts. Locke’s *Two Treatises of Government* (1689) laid the groundwork for limited government and natural rights, while Rousseau’s *The Social Contract* (1762) emphasized popular sovereignty. These ideas, rooted in the intellectual ferment of 18th-century Europe, reshaped political thought and inspired revolutions, from the American Declaration of Independence to the French Revolution.

Cultural influences often act as catalysts for ideological formation. Take conservatism, which arose as a reaction to the rapid changes of the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment. Edmund Burke, in *Reflections on the Revolution in France* (1790), warned against the upheaval of tradition and the dangers of radical reform. His emphasis on organic societal development and the value of inherited institutions resonated in agrarian societies wary of modernity. Similarly, socialism emerged from the cultural and economic dislocations of industrialization. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in *The Communist Manifesto* (1848), diagnosed capitalism’s exploitation of the proletariat and proposed a revolutionary alternative. Their ideas were shaped by the urban poverty and class struggles of 19th-century Europe, offering a blueprint for those seeking economic justice.

Not all ideologies stem from Western contexts. Confucianism, for instance, has profoundly influenced East Asian political thought, emphasizing harmony, hierarchy, and moral governance. Its principles, codified in texts like *The Analects*, shaped imperial China’s bureaucratic systems and continue to inform contemporary governance in countries like Singapore. Similarly, Islamic political thought, rooted in the Quran and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, has evolved into diverse ideologies, from theocratic models to modern interpretations advocating for democratic compatibility. These examples illustrate how cultural and religious traditions provide unique frameworks for political beliefs, often diverging from Western-centric narratives.

The interplay of historical events and individual thinkers is crucial. Fascism, for example, emerged in the aftermath of World War I, fueled by national humiliation, economic instability, and the appeal of strong leadership. Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler exploited these conditions, blending ultranationalism, authoritarianism, and populist rhetoric. Their ideologies were not merely theoretical but deeply pragmatic, designed to mobilize disaffected masses. In contrast, environmentalism, a more recent ideology, has been shaped by scientific discoveries about climate change and resource depletion. Thinkers like Rachel Carson, whose *Silent Spring* (1962) exposed the dangers of pesticides, and political activists like Greta Thunberg, have galvanized global movements. This ideology demonstrates how contemporary challenges can spawn new political frameworks, rooted in both scientific evidence and ethical imperatives.

Understanding the origins of political ideologies requires tracing their historical roots, cultural contexts, and intellectual architects. From the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and rights to the reactionary impulses of conservatism, from Marx’s critique of capitalism to Confucianism’s enduring influence, each ideology reflects its time and place. By studying these origins, we gain insight into why certain beliefs resonate in specific societies and how they adapt to new challenges. This historical lens not only deepens our understanding of political thought but also equips us to navigate the complexities of today’s ideological landscape.

Is Japan Politically Liberal? Exploring Its Governance and Ideological Stance

You may want to see also

Types of Political Ideologies: Liberalism, conservatism, socialism, fascism, and other major ideological frameworks

Political ideologies are the lenses through which societies interpret power, justice, and governance. Among the most influential are liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and fascism, each offering distinct prescriptions for organizing human life. Liberalism champions individual freedoms and limited government intervention, rooted in Enlightenment ideals. Conservatism, by contrast, emphasizes tradition, stability, and gradual change, often prioritizing established institutions. Socialism advocates collective ownership of resources to reduce inequality, while fascism promotes authoritarian nationalism and state control. These frameworks shape policies, cultures, and conflicts globally, often blending or clashing in complex ways.

Consider liberalism, which prioritizes personal liberty, free markets, and democratic governance. Its core principle—that individuals should be free to pursue their interests with minimal state interference—has underpinned modern democracies. However, critics argue it can exacerbate inequality, as seen in neoliberal policies favoring corporations over workers. For instance, tax cuts for the wealthy, a liberal policy, often widen the wealth gap. To mitigate this, proponents suggest pairing free markets with robust social safety nets, as in Nordic countries. This hybrid approach balances individual freedom with collective welfare, illustrating liberalism’s adaptability.

Conservatism, on the other hand, values continuity and skepticism of rapid change. It defends institutions like religion, monarchy, or free markets as anchors of social order. In practice, conservative policies often restrict progressive reforms, such as opposition to same-sex marriage or climate regulations. Yet, conservatism is not monolithic; its expression varies by context. In the U.S., it aligns with fiscal restraint and small government, while in Europe, it may emphasize preserving welfare states. The takeaway? Conservatism’s strength lies in its ability to adapt while preserving core values, though critics see it as resistant to necessary progress.

Socialism challenges capitalism’s inequalities by advocating public or cooperative ownership of production. From Marxist revolutions to Nordic social democracies, its implementations differ widely. For example, Sweden’s high taxes fund universal healthcare and education, reducing poverty without abolishing private enterprise. However, socialist experiments like Venezuela’s have struggled with economic inefficiency and authoritarianism. The key lesson is that socialism’s success depends on balancing equity with economic dynamism, a delicate task often undermined by ideological rigidity or external pressures.

Fascism, a 20th-century phenomenon, merges extreme nationalism with totalitarian control. It rejects individualism and class struggle, instead glorifying the state and a mythical national identity. Fascist regimes, like Mussolini’s Italy or Nazi Germany, suppressed dissent, militarized societies, and targeted minorities. While largely discredited post-WWII, fascist elements persist in contemporary populism, such as xenophobia and strongman leadership. Understanding fascism’s appeal—its promise of order and national revival—is crucial for countering its resurgence. Unlike other ideologies, fascism thrives on crisis, making democratic resilience essential to its containment.

Beyond these four, ideologies like anarchism, environmentalism, and libertarianism offer alternative visions. Anarchism rejects all hierarchies, advocating stateless societies, while environmentalism prioritizes ecological sustainability over economic growth. Libertarianism, a hybrid of liberalism and conservatism, champions absolute individual freedom and minimal government. These frameworks highlight the spectrum of human aspirations, from utopian ideals to pragmatic reforms. Each ideology, with its strengths and flaws, reflects the complexities of governing diverse societies. By studying them, we gain tools to navigate political debates and shape a more just world.

Is Jed Duggar Pursuing a Political Career? Exploring His Ambitions

You may want to see also

Core Principles: Key values, goals, and policies that define and differentiate political ideologies

Political ideologies are not merely abstract concepts but frameworks built on core principles that guide their values, goals, and policies. These principles serve as the ideological DNA, distinguishing one political philosophy from another and shaping how societies are governed. For instance, liberty is a cornerstone of liberalism, while equality is central to socialism. Understanding these core principles is essential for deciphering the motivations and actions of political movements and governments.

Consider the values that underpin ideologies. Conservatism, for example, often prioritizes tradition, stability, and hierarchy, advocating for policies that preserve established institutions. In contrast, progressivism emphasizes innovation, social justice, and reform, pushing for policies that address systemic inequalities. These values are not just theoretical; they manifest in concrete policies like tax structures, education systems, and social welfare programs. A conservative government might favor lower taxes and limited regulation, while a progressive one might advocate for higher taxes on the wealthy and robust public services.

The goals of political ideologies further differentiate them. Capitalism, rooted in free-market principles, aims to maximize economic growth and individual prosperity, often through deregulation and privatization. Socialism, on the other hand, seeks to reduce economic inequality and ensure collective well-being, typically through wealth redistribution and public ownership of key industries. These goals are not mutually exclusive but often compete for dominance in policy debates, reflecting the ideological divides within societies.

Policies are the tangible expressions of these values and goals. Environmentalism, for instance, drives policies like carbon taxes and renewable energy subsidies, reflecting a commitment to sustainability. Authoritarian regimes prioritize order and control, implementing policies such as censorship and surveillance to maintain power. Each policy decision is a manifestation of the underlying ideology, making it crucial to trace policies back to their core principles to understand their intent and impact.

In practice, identifying the core principles of an ideology requires critical analysis. Start by examining its foundational texts, historical contexts, and key figures. For example, Marxism’s critique of capitalism is rooted in its core principle of class struggle. Next, observe how these principles translate into policies and actions. A libertarian ideology, emphasizing individual freedom, would oppose strict regulations, while an environmentalist ideology would prioritize ecological preservation. Finally, evaluate the trade-offs and contradictions within ideologies. Even within liberalism, there are debates between prioritizing individual rights versus collective welfare, highlighting the complexity of core principles.

By dissecting the core principles of political ideologies—their values, goals, and policies—we gain a clearer understanding of their distinct identities and the implications for governance. This analytical lens not only demystifies political discourse but also empowers individuals to engage critically with the ideologies shaping their world.

Are Canadians Truly Polite? Unraveling the Stereotype and Reality

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role in Governance: How ideologies influence policy-making, institutions, and societal structures

Political ideologies are not mere abstract concepts; they are the blueprints that shape governance. Consider how a liberal ideology prioritizes individual freedoms and free markets, often leading to policies that deregulate industries and reduce government intervention. Conversely, a socialist ideology emphasizes collective welfare and economic equality, resulting in policies like progressive taxation and public healthcare. These ideological frameworks dictate not only the content of policies but also the very structure of institutions, determining whether power is centralized or decentralized, and how resources are allocated.

To understand the practical impact, examine the role of ideology in institution-building. In democratic societies rooted in liberal ideology, institutions like independent judiciaries and free press are designed to safeguard individual rights. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often dismantle such institutions, replacing them with mechanisms that enforce ideological conformity. For instance, China’s Communist Party has restructured governance to align with socialist principles, creating state-owned enterprises and a single-party system. The takeaway is clear: ideologies are not passive observers of governance; they are active architects of its framework.

A persuasive argument can be made that ideologies also shape societal structures by defining norms and values. A conservative ideology, for example, often reinforces traditional family structures and religious institutions, influencing policies on marriage, education, and social welfare. Conversely, progressive ideologies challenge these norms, advocating for gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and secular governance. These ideological battles play out in policy debates, such as those surrounding abortion rights or same-sex marriage, where the underlying values of competing ideologies clash. The result is a society molded in the image of its dominant or contested ideologies.

Finally, consider the cautionary tale of ideological rigidity. When ideologies become dogmatic, they can stifle adaptability and innovation in governance. For instance, strict adherence to laissez-faire economics during the 2008 financial crisis exacerbated economic inequality, as ideological opposition to government intervention delayed necessary bailouts. Similarly, socialist regimes that prioritize state control over market dynamics often struggle with inefficiency and stagnation. The key is to balance ideological commitment with pragmatic flexibility, ensuring that governance remains responsive to societal needs. In this way, ideologies can serve as guiding principles rather than straitjackets.

Understanding Texas Politics: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Unique System

You may want to see also

Evolution Over Time: Adaptation, decline, and resurgence of ideologies in response to global changes

Political ideologies are not static; they evolve in response to shifting global landscapes, adapting to new realities or declining under the weight of their own contradictions. Consider the trajectory of socialism. Born in the 19th century as a critique of industrial capitalism’s exploitation, it surged in the early 20th century with the Russian Revolution and the rise of welfare states in Europe. Yet, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked its apparent decline, as free-market capitalism seemed triumphant. However, the 2008 financial crisis and rising inequality have fueled a resurgence of socialist ideas, with figures like Bernie Sanders and movements like Democratic Socialism gaining traction. This cyclical pattern—rise, fall, and rebirth—illustrates how ideologies adapt to address new societal challenges.

Adaptation is key to an ideology’s survival. Liberalism, for instance, has undergone significant transformations since its Enlightenment origins. Classical liberalism emphasized individual freedoms and limited government, but the Great Depression and World War II exposed the need for state intervention to ensure social welfare. This led to the emergence of modern liberalism, which balances individual rights with collective responsibilities, as seen in the creation of social safety nets and progressive taxation. Today, liberalism faces new tests from globalization, automation, and climate change, prompting debates about its scope and priorities. Its ability to evolve—while retaining core principles—demonstrates the resilience of adaptable ideologies.

Decline often occurs when ideologies fail to address emerging realities or become rigid in their application. Fascism, which rose in the early 20th century as a reaction to economic instability and national humiliation, promised order and national glory but was discredited by its association with genocide and totalitarianism. Despite occasional resurgences in fringe movements, its core tenets remain largely repudiated. Similarly, communism’s decline was accelerated by its inability to deliver economic prosperity or political freedom, leading to widespread disillusionment. These examples highlight how ideologies tied to specific historical contexts or flawed implementations struggle to endure.

Resurgence, on the other hand, often occurs when ideologies offer solutions to contemporary crises. Environmentalism, once a niche concern, has evolved into a global movement as climate change has become an existential threat. Green parties and eco-socialist ideologies are gaining ground, integrating ecological sustainability with social justice. Similarly, conservatism has experienced periodic revivals by rebranding itself in response to cultural shifts, as seen in the rise of neoconservatism in the 1980s or the populist wave of the 2010s. These resurrections show how ideologies can recapture relevance by aligning with urgent global priorities.

To understand the evolution of ideologies, observe their interplay with technology, economics, and culture. For instance, the digital age has spurred debates about data privacy, surveillance, and the role of tech giants, prompting adaptations in liberal and conservative thought alike. Practical tips for tracking these shifts include monitoring policy changes, analyzing electoral trends, and engaging with diverse media sources. By studying how ideologies adapt, decline, or resurface, we gain insight into the dynamic relationship between ideas and the ever-changing world they seek to shape.

Whistleblower's Allegations: Uncovering Potential Political Bias and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political ideology refers to a set of beliefs, values, and principles that outline how a society should be organized, governed, and managed, often guiding political actions and policies.

Political ideology shapes government decisions by providing a framework for addressing issues like economic distribution, social rights, and individual freedoms, influencing laws, regulations, and public programs.

Major political ideologies include liberalism, conservatism, socialism, communism, fascism, and environmentalism, each with distinct views on governance, economics, and social structures.