Political generation refers to a cohort of individuals who share similar political experiences, values, and beliefs shaped by the historical, social, and cultural contexts of their formative years. These cohorts are often defined by pivotal events, such as wars, economic crises, or social movements, which influence their collective worldview and approach to politics. Unlike chronological age groups, political generations are united by their responses to shared challenges and opportunities, creating distinct attitudes toward governance, policy, and societal change. Understanding political generations is crucial for analyzing voting patterns, ideological shifts, and the evolution of political discourse, as each generation tends to prioritize different issues and advocate for unique solutions based on their lived experiences.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A cohort of individuals who share similar political experiences, beliefs, and formative events during a specific time period. |

| Age Range | Typically spans 15–20 years, though can vary based on historical context. |

| Formative Events | Shared historical, social, or political events that shape their worldview (e.g., 9/11, the Great Recession, COVID-19). |

| Political Beliefs | Tend to align on key issues like climate change, social justice, or economic policies based on their formative experiences. |

| Technological Influence | Shaped by the technology prevalent during their formative years (e.g., Millennials with the rise of the internet, Gen Z with social media). |

| Voting Behavior | Often exhibit distinct voting patterns influenced by their generational values and priorities. |

| Social Attitudes | Reflect attitudes toward diversity, gender equality, and global issues shaped by their era. |

| Economic Outlook | Influenced by economic conditions during their formative years (e.g., student debt, job market challenges). |

| Examples | Silent Generation (1928–1945), Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Gen X (1965–1980), Millennials (1981–1996), Gen Z (1997–2012). |

| Intergenerational Conflict | Often arises due to differing values and priorities between generations (e.g., Boomers vs. Millennials on housing or climate policy). |

| Cultural Identity | Defined by shared cultural references, media, and societal norms of their time. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Concept: Understanding the term political generation and its significance in political science

- Historical Context: Examining how political generations have evolved over time and across societies

- Cohort Analysis: Studying shared experiences and beliefs that define distinct political generations

- Impact on Policy: Exploring how political generations influence policy-making and governance

- Generational Conflict: Analyzing tensions between different political generations in societal and political arenas

Definition and Concept: Understanding the term political generation and its significance in political science

The term "political generation" refers to a cohort of individuals who share a similar age range and have experienced pivotal political events or shifts during their formative years. These events shape their political beliefs, values, and behaviors, often distinguishing them from older or younger groups. For instance, the Silent Generation, born between 1928 and 1945, came of age during the Cold War and McCarthyism, fostering a tendency toward conformity and caution in political expression. In contrast, Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, were shaped by the 9/11 attacks and the Great Recession, leading to a focus on social justice and economic reform. Understanding these generational distinctions is crucial for political scientists analyzing voting patterns, policy preferences, and societal change.

Analyzing political generations requires a multi-step approach. First, identify the defining political events or eras that coincide with a generation’s formative years, typically ages 18 to 25. For example, Generation X, born between 1965 and 1980, grew up during the Reagan era and the end of the Cold War, which influenced their skepticism of government and emphasis on individualism. Second, examine how these events translate into specific political attitudes or actions. Studies show that Millennials and Gen Z are more likely to support progressive policies like climate action and healthcare reform, while Baby Boomers often prioritize fiscal conservatism. Caution must be taken, however, to avoid overgeneralization, as generational trends are not absolute and can vary by region, race, or socioeconomic status.

A persuasive argument for the significance of political generations lies in their predictive power. By understanding generational tendencies, political parties can tailor their messaging and policies to resonate with specific cohorts. For instance, campaigns targeting Gen Z might focus on social media platforms and issues like student debt, while appeals to Baby Boomers could emphasize traditional values and economic stability. This strategic approach is evident in recent elections, where younger generations have driven shifts toward progressive candidates, while older voters have maintained support for conservative platforms. However, this dynamic is not static; generational priorities can evolve as new events occur, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which may further differentiate Gen Z from Millennials.

Comparatively, political generations also highlight intergenerational tensions and collaborations. For example, the generational divide on issues like climate change often pits younger, more activist-oriented groups against older generations who may prioritize economic growth. Yet, these differences can also foster dialogue and compromise, as seen in multi-generational movements like the Women’s March or Black Lives Matter. Political scientists must therefore study not only how generations differ but also how they intersect and influence one another. This comparative lens reveals the fluidity of generational identities and their role in shaping political landscapes over time.

Practically, recognizing political generations offers actionable insights for policymakers and activists. For instance, initiatives aimed at increasing youth voter turnout, such as lowering the voting age or expanding civic education, can empower younger generations to shape policies that reflect their values. Similarly, intergenerational programs can bridge divides by fostering mutual understanding and collaboration. A specific example is the “Climate Grandplans” initiative, where younger activists pair with older volunteers to advocate for environmental policies. Such efforts demonstrate how awareness of political generations can translate into tangible strategies for addressing societal challenges. By grounding analysis in generational dynamics, political science gains a powerful tool for understanding and influencing the future of politics.

Do Political Maps Accurately Represent International Borders?

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Examining how political generations have evolved over time and across societies

The concept of political generations is not static; it is a dynamic framework shaped by historical events, societal shifts, and cultural contexts. To understand its evolution, consider the post-World War II era, where the "Silent Generation" emerged in the West, marked by a collective focus on stability, conformity, and rebuilding after global devastation. This generation’s political outlook was deeply influenced by the Cold War, McCarthyism, and the rise of suburban conservatism. In contrast, the same period in post-colonial societies saw the rise of generations driven by anti-imperialist struggles, nationalism, and the quest for self-determination, as exemplified by the Mau Mau movement in Kenya or the Algerian War of Independence. These divergent trajectories highlight how political generations are forged in the crucible of their unique historical moments.

Analyzing the 1960s and 1970s reveals a global generational shift toward activism and rebellion. The Baby Boomers in the United States and Western Europe championed civil rights, anti-war movements, and countercultural ideals, while their counterparts in the Global South fought against dictatorships and economic inequality, as seen in the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico or the Cultural Revolution in China. This era underscores the interplay between local and global forces in shaping political generations. For instance, the 1968 protests were a worldwide phenomenon, yet their demands and outcomes varied dramatically across societies, reflecting distinct historical contexts and power structures.

A comparative lens reveals how political generations adapt to technological and economic transformations. The Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, came of age during the digital revolution and the 2008 financial crisis, fostering a generation skeptical of traditional institutions and increasingly focused on issues like climate change and student debt. In contrast, their peers in emerging economies, such as India or Brazil, faced additional challenges like rapid urbanization and political instability, shaping their priorities around development and governance. This generational divergence illustrates how global trends intersect with local realities to produce unique political identities.

To examine the evolution of political generations, consider the following steps: first, identify the defining historical events of a given era, such as wars, economic crises, or technological breakthroughs. Second, analyze how these events influenced the values, beliefs, and behaviors of the generation in question. Third, compare these findings across societies to uncover both commonalities and differences. For example, while Generation Z in the West is often associated with digital activism and progressive politics, their counterparts in authoritarian regimes may prioritize survival and resistance. This structured approach provides a framework for understanding the complex interplay between history and generational identity.

A persuasive argument can be made that political generations are not merely passive recipients of history but active agents in shaping it. The Arab Spring, for instance, was driven by young people across the Middle East and North Africa who leveraged social media to challenge entrenched regimes, demonstrating the power of generational cohesion in driving political change. Similarly, the global youth climate movement led by figures like Greta Thunberg exemplifies how contemporary generations are redefining political engagement in response to existential threats. These examples underscore the agency of political generations in both reflecting and transforming their historical contexts.

In conclusion, the evolution of political generations is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of history, culture, and societal change. By examining specific eras, comparing global trends, and analyzing generational responses to key events, we gain a nuanced understanding of how political identities are formed and transformed. This historical context not only illuminates the past but also offers insights into the future, as each new generation navigates its own unique challenges and opportunities.

Understanding Political Runoffs: A Comprehensive Guide to How They Work

You may want to see also

Cohort Analysis: Studying shared experiences and beliefs that define distinct political generations

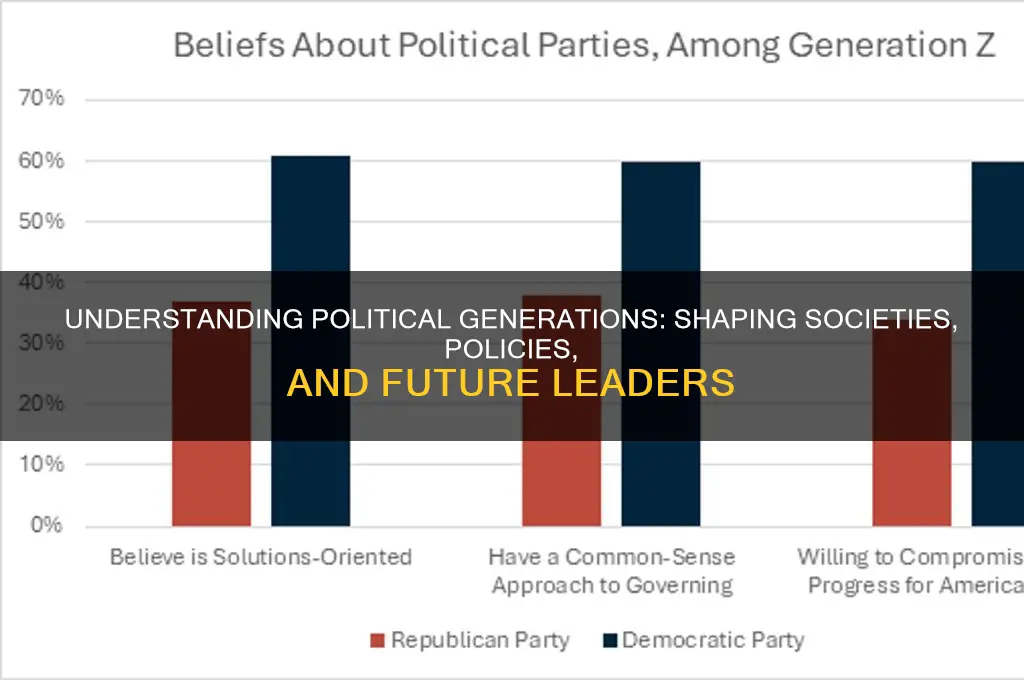

Political generations are shaped by the unique historical, social, and economic contexts in which they come of age. Cohort analysis offers a powerful lens to dissect these generations, revealing how shared experiences and beliefs forge distinct political identities. By examining specific age groups—such as Millennials (born 1981–1996) or Gen Z (born 1997–2012)—researchers can identify patterns in their attitudes toward issues like climate change, economic inequality, or social justice. For instance, Millennials, who entered adulthood during the 2008 financial crisis, often prioritize financial stability and progressive policies, while Gen Z, raised in the age of social media activism, tends to focus on intersectional advocacy and digital mobilization.

To conduct cohort analysis effectively, start by defining clear age brackets and timeframes. For example, analyze how individuals aged 18–25 during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement differ from those in the same age range during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. Next, gather data on key events, policies, and cultural shifts that influenced these groups. Surveys, historical records, and longitudinal studies are invaluable tools. Caution: avoid oversimplifying generational traits, as individual variation within cohorts can be significant. Instead, focus on identifying overarching trends that distinguish one generation from another.

A persuasive argument for cohort analysis lies in its ability to predict political behavior. Understanding generational beliefs can help policymakers tailor messages and policies to resonate with specific groups. For example, framing climate action as an economic opportunity might appeal to Millennials, while emphasizing its moral urgency could galvanize Gen Z. However, this approach requires nuance; generational stereotypes can alienate individuals who don’t fit the mold. The takeaway? Use cohort analysis as a starting point, not a definitive guide, to engage diverse audiences effectively.

Comparatively, cohort analysis also highlights how generations interact and influence one another. Baby Boomers (born 1946–1964), shaped by post-WWII optimism, often clash with younger generations over issues like healthcare and technology. Yet, intergenerational collaboration—such as joint activism on climate change—shows that shared goals can bridge divides. Descriptively, imagine a family dinner where a Boomer parent and their Gen Z child debate student debt: their differing perspectives reflect not just age, but the distinct eras that molded their worldviews.

In practice, cohort analysis is a dynamic tool for anyone studying political behavior. Begin by identifying the generational cohort of interest, then map their formative experiences against their current beliefs. For instance, track how Gen X’s (born 1965–1980) skepticism of institutions, rooted in the Reagan era and the AIDS crisis, influences their political engagement today. Pair quantitative data with qualitative insights, such as interviews or focus groups, to capture the complexity of generational identities. By doing so, you’ll uncover not just what defines a political generation, but how their legacy shapes the future.

Troubleshooting Politico Notifications: Quick Fixes for Common Alert Issues

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on Policy: Exploring how political generations influence policy-making and governance

Political generations, shaped by shared historical events, cultural shifts, and socioeconomic conditions, wield significant influence over policy-making and governance. For instance, the Silent Generation (born 1928–1945), marked by the Great Depression and World War II, tends to prioritize fiscal conservatism and national security, often advocating for balanced budgets and strong defense policies. In contrast, Millennials (born 1981–1996), coming of age during the 2008 financial crisis and the rise of the internet, lean toward progressive policies like student debt relief and climate action. These generational differences create a dynamic tension in legislative bodies, where older lawmakers may resist reforms pushed by their younger counterparts, slowing policy evolution.

To understand this impact, consider the generational makeup of a legislature. In the U.S. Congress, the average age of senators is 64, while the House of Representatives averages 58. This skews policy debates toward the perspectives of older generations, often at the expense of issues like affordable housing or digital privacy, which resonate more with younger voters. For policymakers aiming to bridge this gap, a practical tip is to establish bipartisan generational caucuses. These groups can foster dialogue between lawmakers of different age groups, ensuring that policies reflect a broader spectrum of experiences. For example, a joint caucus could tackle student loan reform by combining the fiscal caution of older members with the urgency felt by younger ones.

Generational influence isn’t just about age—it’s about worldview. Baby Boomers (born 1946–1964), shaped by the civil rights movement and the Cold War, often champion individualism and economic growth, leading to policies favoring tax cuts and deregulation. Meanwhile, Gen Z (born 1997–2012), raised in the era of school shootings and global pandemics, prioritizes collective safety and systemic change, pushing for gun control and healthcare reform. This clash of values can stall progress, as seen in debates over healthcare expansion, where Boomer-led resistance to single-payer systems contrasts with Gen Z’s demand for universal coverage. Policymakers can mitigate this by incorporating generational impact assessments into legislative proposals, similar to environmental impact studies, to ensure policies address the needs of all age groups.

A cautionary note: overemphasizing generational divides can lead to stereotypes and polarization. Not all members of a generation think alike, and individual beliefs are shaped by factors like race, gender, and geography. For instance, while Millennials are often labeled as liberal, a significant portion identifies as conservative, particularly in rural areas. To avoid oversimplification, policymakers should use generational data as a starting point, not a definitive guide. Conducting focus groups across age, region, and identity can provide a more nuanced understanding of public opinion. Additionally, leveraging technology—such as social media polls or AI-driven surveys—can help capture the diverse voices within each generation.

In conclusion, political generations act as invisible architects of policy, shaping priorities and outcomes in ways both subtle and profound. By recognizing these influences, policymakers can craft more inclusive and forward-thinking governance. A practical step is to mandate generational diversity in advisory boards and committees, ensuring that decisions reflect the experiences of all age groups. For instance, a climate policy task force could include representatives from Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, and Boomers to balance short-term economic concerns with long-term environmental sustainability. Ultimately, understanding and addressing generational dynamics isn’t just about fairness—it’s about building policies that stand the test of time.

Casablanca's Political Symbolism: A Cinematic Reflection of Global Power Struggles

You may want to see also

Generational Conflict: Analyzing tensions between different political generations in societal and political arenas

Political generations, often defined by shared formative experiences and historical contexts, shape distinct worldviews and priorities. For instance, the Silent Generation, born between 1928 and 1945, came of age during the Cold War and civil rights movement, fostering a tendency toward conformity and institutional trust. In contrast, Millennials (1981–1996) grew up during the rise of the internet and the 9/11 era, leading to a focus on individualism, technological fluency, and skepticism of traditional institutions. These differences often manifest as generational conflict, where competing values and priorities clash in societal and political arenas.

Consider the debate over climate policy. Younger generations, like Gen Z (1997–2012), view climate change as an existential threat, demanding immediate and radical action. They mobilize through social media and grassroots movements, pushing for policies like the Green New Deal. Meanwhile, older generations, such as Baby Boomers (1946–1964), may prioritize economic stability and incremental change, citing concerns about job losses in fossil fuel industries. This tension is not merely ideological but structural: younger generations will inherit the consequences of today’s decisions, while older generations hold disproportionate political and economic power.

To navigate these conflicts, it’s instructive to adopt a multi-generational approach in policy-making. For example, intergenerational forums can foster dialogue and mutual understanding. In Germany, the “Council of the Ages” brings together citizens from different age groups to discuss national issues, ensuring diverse perspectives are heard. Similarly, mentorship programs can bridge gaps by pairing younger activists with experienced policymakers, combining idealism with pragmatism. Practical steps include mandating age diversity on advisory boards and incorporating generational impact assessments into legislation.

However, caution is necessary. Stereotyping generations can oversimplify complex issues and deepen divides. Not all Millennials support progressive policies, nor do all Boomers resist change. Context matters: in countries with aging populations, generational conflict may revolve around pension reforms, while in youth-majority nations, it could center on education funding. Tailoring solutions to local demographics and cultural norms is essential. For instance, in Japan, where the elderly comprise 28% of the population, policies balancing elder care with youth opportunities are critical.

Ultimately, generational conflict is not inherently destructive. When managed constructively, it can drive innovation and progress. History shows that societal breakthroughs often emerge from intergenerational collaboration, such as the civil rights movement, where younger activists worked alongside older leaders. By acknowledging differences, fostering dialogue, and designing inclusive policies, societies can transform generational tensions into a catalyst for collective advancement. The key lies in recognizing that each generation brings unique strengths—and that the future requires the wisdom of experience paired with the energy of youth.

Politics in Sports: Should Athletes Speak Out or Stay Silent?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political generation refers to a group of individuals who share similar political experiences, values, and beliefs due to living through the same historical, social, and political events during their formative years.

While a demographic generation is defined by birth years and shared age-related experiences, a political generation is shaped by collective exposure to significant political events, ideologies, and societal shifts, regardless of age.

Understanding political generations helps explain voting patterns, policy preferences, and societal attitudes, as shared political experiences often influence how groups perceive and engage with political issues and institutions.