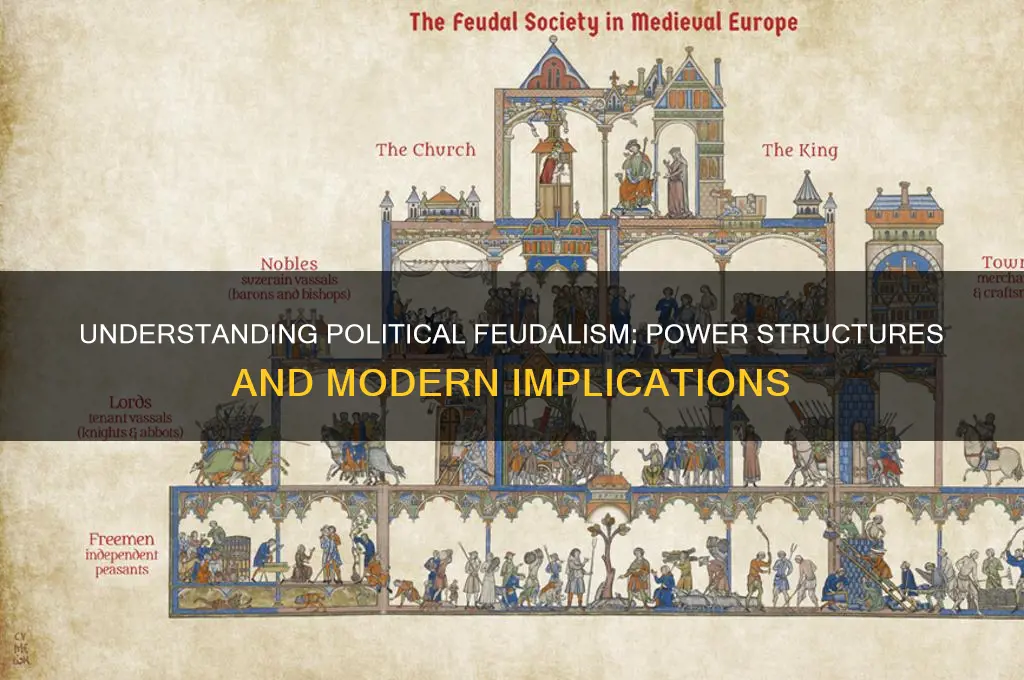

Political feudalism is a system of governance characterized by decentralized power, where authority is distributed among local lords or nobles who control territories in exchange for loyalty and service to a higher sovereign, typically a monarch. Rooted in medieval Europe, this structure emerged as a response to the decline of centralized Roman authority, creating a hierarchical arrangement of mutual obligations between lords and vassals. In this system, land ownership and military protection were the primary currencies of power, with peasants often bound to the land as serfs. While feudalism provided stability and security in a fragmented political landscape, it also entrenched social inequality and limited mobility. Understanding political feudalism offers insights into the evolution of governance, the dynamics of power, and the historical foundations of modern political systems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Decentralized Power | Power is distributed among local lords or elites rather than centralized in a single authority. |

| Hierarchy of Authority | A rigid social hierarchy exists, with the monarch or supreme ruler at the top, followed by nobles, knights, and peasants. |

| Land Ownership | Land is the primary source of wealth and power, owned by the nobility and worked by peasants in exchange for protection. |

| Vassalage and Feudal Contracts | Relationships between lords and vassals are based on mutual obligations, such as military service, loyalty, and economic support. |

| Limited State Institutions | Weak or absent centralized state institutions, with local lords administering justice, collecting taxes, and maintaining order. |

| Hereditary Privileges | Titles, lands, and privileges are inherited, reinforcing the social hierarchy and power structures. |

| Local Autonomy | Local lords have significant autonomy in governing their territories, often with little interference from higher authorities. |

| Military Service | Military obligations are a key aspect of feudal relationships, with vassals providing knights and soldiers to their lords. |

| Economic Dependence | Peasants are economically dependent on their lords, often tied to the land through serfdom or similar systems. |

| Limited Social Mobility | Social mobility is restricted, with individuals generally remaining in the social class into which they are born. |

| Customary Law | Local customs and traditions often take precedence over formal legal systems, with laws varying widely between regions. |

| Weak Monetary Economy | The economy is largely agrarian and self-sufficient, with limited use of money and a focus on barter and subsistence farming. |

| Religious Influence | The Church plays a significant role in feudal society, often owning land and influencing political and social norms. |

| Fragmented Political Landscape | Political power is fragmented among numerous local lords, leading to frequent conflicts and alliances. |

| Lack of National Identity | A strong national identity is often absent, with loyalties primarily to local lords or regions rather than a broader nation-state. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of feudalism: Historical roots and development of feudal systems in various societies

- Political hierarchy: Structure of lord-vassal relationships and power distribution in feudalism

- Economic foundations: Role of land ownership, serfdom, and agrarian economies in feudal systems

- Legal frameworks: Feudal laws, customs, and obligations shaping political and social order

- Decline of feudalism: Factors leading to the erosion and transformation of feudal structures

Origins of feudalism: Historical roots and development of feudal systems in various societies

Feudalism, as a political and economic system, did not emerge in a vacuum but evolved from specific historical conditions and societal needs. Its origins can be traced to the fragmentation of centralized authority in the Roman Empire during the 5th century CE. As Roman institutions collapsed, local leaders and military commanders filled the power void, establishing personal networks of loyalty and protection. These relationships, rooted in land grants and military service, laid the groundwork for feudal structures. For instance, the Roman practice of granting land to soldiers (known as *hospites*) in exchange for military service foreshadowed the feudal system’s core dynamic: land tenure in return for obligations.

The development of feudalism was not uniform across societies; it adapted to local contexts and cultural norms. In medieval Europe, the Carolingian Empire’s decline in the 9th century accelerated feudalism’s rise. Charlemagne’s vast territories became unmanageable, leading to the delegation of power to local nobles (*vassals*). These nobles, in turn, subdivided their lands among lesser lords, creating a hierarchical pyramid of loyalty and service. This system was codified in documents like the *Capitulary of Quierzy* (877 CE), which formalized the hereditary nature of fiefs. Similarly, in Japan, the Heian period (794–1185 CE) saw the emergence of a feudal system known as *bakufu*, where the shogun and daimyo controlled land and samurai warriors in exchange for military service.

A comparative analysis reveals that feudalism often arose in response to external threats and internal instability. In both Europe and Japan, invasions—by Vikings and Mongols, respectively—forced rulers to decentralize power and rely on local strongmen for defense. This pragmatic response to insecurity transformed ad hoc alliances into institutionalized systems. For example, the English feudal system, solidified after the Norman Conquest of 1066, was a direct response to the need for military organization and territorial control. William the Conqueror’s *Domesday Book* (1086 CE) meticulously recorded land holdings and obligations, illustrating the system’s bureaucratic underpinnings.

To understand feudalism’s persistence, consider its self-sustaining mechanisms. The system was not merely political but also economic and social, intertwining land ownership with status and power. Peasants, bound to the land as serfs, formed the base of the pyramid, providing labor and resources that sustained the entire structure. This interdependence ensured that feudalism endured for centuries, even as central authorities reasserted control. For instance, the Holy Roman Empire and the French monarchy gradually reclaimed power through administrative reforms, but feudal elements persisted in local governance until the early modern period.

In conclusion, the origins of feudalism are deeply rooted in historical crises and the human need for security and order. Its development across societies demonstrates a shared response to decentralization and external threats, though its expression varied widely. By examining these origins, we gain insight into how political systems adapt to survive—and how their legacies shape modern institutions. Practical takeaways include recognizing the role of local power dynamics in state formation and the enduring impact of historical solutions to societal challenges.

Discover Your Political Identity: Unraveling Ideologies and Personal Beliefs

You may want to see also

Political hierarchy: Structure of lord-vassal relationships and power distribution in feudalism

Feudalism, a political system prevalent in medieval Europe, was built on a hierarchical structure of lord-vassal relationships, where power and land were exchanged for loyalty and service. At the apex of this pyramid stood the monarch, who granted vast territories to nobles in return for military support and governance. These nobles, in turn, subdivided their lands among lesser lords, creating a cascading system of obligations and dependencies. This structure ensured stability by distributing authority while maintaining a clear chain of command, but it also entrenched inequality, as power was concentrated in the hands of a few.

Consider the mechanics of this hierarchy: a vassal would pledge fealty to a lord through a ceremonial oath, often involving symbolic gestures like kneeling and kissing hands. In exchange, the lord would grant the vassal a fief—a piece of land—which provided the vassal with resources and status. However, this arrangement was not static; vassals were required to provide military service, counsel, and financial aid to their lords when called upon. Failure to fulfill these duties could result in the forfeiture of the fief, ensuring compliance through the threat of economic ruin. This system of mutual obligations created a delicate balance of power, where loyalty was both a moral and practical necessity.

One illustrative example is the relationship between William the Conqueror and his nobles after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. William distributed land to his followers, who became tenants-in-chief, responsible for administering their territories and providing knights for his army. These tenants, in turn, granted smaller parcels of land to sub-vassals, who owed them service. This layered structure ensured that William’s authority extended throughout the kingdom, even as local governance was delegated. However, it also created tensions, as vassals often sought to expand their autonomy, leading to conflicts like the Anarchy in the 12th century.

To understand the power distribution in feudalism, imagine a pyramid with the monarch at the top and peasants at the base. Each layer of lords and vassals acted as intermediaries, filtering authority downward while extracting resources upward. This system was inherently unequal, as vassals relied on their lords for protection and livelihood, while lords depended on vassals for labor and military strength. The hierarchy was further reinforced by legal and social norms, such as the concept of *honour* and the rigid class distinctions between nobility, clergy, and commoners.

In practice, managing this hierarchy required careful negotiation and strategic alliances. Lords often sought to strengthen their position by marrying into powerful families or acquiring additional fiefs, while vassals might play lords against each other to gain leverage. For instance, a vassal might offer increased service to one lord in exchange for protection from another. This dynamic interplay of loyalty and self-interest made feudalism both resilient and fragile, as it relied on personal relationships rather than formal institutions.

Ultimately, the lord-vassal relationship in feudalism was a pragmatic solution to the challenges of medieval governance, balancing centralized authority with local autonomy. While it provided stability in an era of limited communication and infrastructure, it also perpetuated a system of privilege and exploitation. Understanding this structure offers insights into how power can be distributed—and abused—in hierarchical systems, a lesson relevant even in modern political and organizational contexts.

Reporting Political Texts: A Step-by-Step Guide to Taking Action

You may want to see also

Economic foundations: Role of land ownership, serfdom, and agrarian economies in feudal systems

Feudalism, as a political and economic system, hinged on the control of land, a resource so vital that it became the cornerstone of power and wealth. Land ownership was not merely a symbol of status but the very foundation of feudal economies. In this system, the nobility held vast tracts of land, often granted by the monarch, and derived their authority and income from these holdings. The land was the primary means of production, and its ownership dictated the social hierarchy, with the lord at the top and the peasants, or serfs, bound to the soil.

The relationship between land ownership and serfdom is a critical aspect of feudalism's economic structure. Serfs were not slaves but were legally tied to the land they worked, providing labor in exchange for protection and the right to cultivate a portion of the land for their own sustenance. This system, known as manorialism, created a self-sufficient estate where the lord's land was the economic engine. Serfs typically worked the lord's fields for several days a week and paid rent in the form of crops or labor, leaving them with limited time and resources to tend to their own plots. This arrangement ensured a steady supply of agricultural produce for the lord while keeping the serfs in a state of dependence.

Agrarian economies dominated feudal societies, with agriculture being the primary, if not sole, industry. The focus on land and its cultivation meant that technological advancements and economic growth were often directed towards improving agricultural productivity. Innovations like the heavy plow and three-field crop rotation system in medieval Europe increased food production, allowing for population growth and the emergence of surplus. This surplus was crucial, as it provided the means for lords to support non-agricultural specialists such as blacksmiths, weavers, and clergy, fostering a rudimentary division of labor.

The economic power of the feudal lord was directly linked to the productivity of his land and the efficiency of his serfs' labor. Lords often had the authority to impose taxes, known as feudal incidents, on their serfs, which could include payments for using the lord's mill or oven, or fees for marrying or inheriting land. These payments were typically made in kind, with a portion of the serf's produce going to the lord. Over time, some of these obligations evolved into monetary payments, reflecting the gradual monetization of the feudal economy.

In essence, the economic foundations of feudalism were built upon a complex interplay of land ownership, serfdom, and agrarian production. This system created a hierarchical structure where economic power was concentrated in the hands of the landowning elite, shaping social relationships and political dynamics for centuries. Understanding these economic underpinnings is crucial to comprehending the broader implications of political feudalism and its enduring impact on societies that emerged from this era.

Understanding Political Crimes: Definitions, Examples, and Legal Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legal frameworks: Feudal laws, customs, and obligations shaping political and social order

Feudalism, as a political and social system, was underpinned by a complex web of legal frameworks that defined relationships, obligations, and hierarchies. At its core, feudal law was not a codified system but a patchwork of customs, traditions, and agreements that evolved over centuries. These laws were deeply personal, often tied to specific individuals and their roles within the feudal hierarchy, from kings and lords to vassals and peasants. The legal structure was decentralized, with local customs and lordly decrees holding as much weight as any royal edict, creating a mosaic of obligations that shaped daily life.

One of the key legal mechanisms in feudalism was the feudal contract, a mutual agreement between a lord and a vassal. This contract, often sealed by the symbolic act of homage, established the vassal’s loyalty and military service in exchange for a fief—land or resources. The obligations were reciprocal: the lord provided protection and maintenance of order, while the vassal owed service, counsel, and, in some cases, financial contributions. These relationships were not static; they could be renegotiated, inherited, or dissolved, often leading to disputes that were resolved through feudal courts or trial by combat. The flexibility of these arrangements allowed the system to adapt, but it also created ambiguity, as interpretations of obligations varied widely across regions.

Custom played an equally critical role in shaping feudal legal frameworks. Local traditions often dictated how land was inherited, how disputes were settled, and how social roles were defined. For instance, in some regions, primogeniture became the norm, where the eldest son inherited the entirety of the estate, while in others, land was divided among all heirs. These customs were rarely written down but were enforced through community consensus and the authority of local lords. The interplay between formal law and custom created a dynamic legal environment where precedent and practice often trumped written rules, making feudalism a system deeply rooted in its historical and cultural context.

The obligations within feudalism extended beyond the lord-vassal relationship to encompass the entire social order. Peasants, who formed the majority of the population, were bound by manorial laws that dictated their labor, taxes, and rights. These obligations were often harsh, with peasants required to work the lord’s land, pay rents in kind, and seek permission for marriages or travel. Yet, these laws also provided a degree of security, as peasants were entitled to protection and access to common resources. The legal framework thus reinforced social stratification while ensuring a degree of interdependence, as each class relied on the others for survival and stability.

In analyzing feudal legal frameworks, it becomes clear that their strength lay in their adaptability and their weakness in their inconsistency. While the system provided a clear structure for governance and social order, its reliance on personal relationships and local customs made it vulnerable to abuse and fragmentation. The legacy of feudal law can be seen in modern legal systems, particularly in concepts of property rights, contractual obligations, and the balance between central authority and local autonomy. Understanding these frameworks offers valuable insights into how legal systems evolve to reflect the needs and values of their societies.

Unveiling Political Bias: Analyzing News Media's Ideological Slant and Impact

You may want to see also

Decline of feudalism: Factors leading to the erosion and transformation of feudal structures

The decline of feudalism was not a sudden event but a gradual process influenced by a myriad of interconnected factors. One of the primary catalysts was the Black Death, which ravaged Europe in the 14th century. This pandemic decimated the population, reducing the number of peasants available to work the land. As labor became scarce, surviving peasants gained bargaining power, demanding better wages and conditions. This shift disrupted the feudal system’s foundation, which relied on a fixed hierarchy of obligations and servitude. Landowners, unable to maintain their estates with dwindling labor, were forced to adapt, often granting peasants greater freedoms or transitioning to wage-based labor systems.

Another critical factor was the rise of centralized monarchies. As kings and queens consolidated power, they sought to diminish the influence of feudal lords who had historically held significant autonomy. By establishing bureaucratic systems, standardized laws, and national armies, monarchs weakened the feudal structure from within. For instance, the Hundred Years' War between England and France demonstrated the inefficiency of feudal levies compared to professional armies, further eroding the military relevance of feudal lords. This centralization of authority gradually rendered feudal obligations obsolete, as monarchs became the ultimate source of power and protection.

Economic transformations also played a pivotal role in the decline of feudalism. The growth of trade and urbanization created new opportunities for wealth accumulation outside the agrarian economy. Merchants and artisans in burgeoning towns challenged the feudal order by accumulating capital independently of land ownership. The emergence of a money-based economy undermined the barter system inherent in feudal relationships, as peasants and lords alike began to prioritize cash transactions over traditional obligations. This shift not only weakened feudal ties but also fostered a middle class that demanded political and social reforms.

Lastly, intellectual and cultural changes contributed to the erosion of feudal structures. The Renaissance and the Reformation challenged traditional authority, promoting individualism and questioning the divine right of kings and lords. These movements encouraged critical thinking and the pursuit of knowledge, undermining the static social hierarchy of feudalism. For example, the printing press disseminated ideas widely, empowering common people with access to information previously controlled by the elite. This cultural shift, combined with economic and political changes, created an environment where feudalism could no longer thrive.

In summary, the decline of feudalism was driven by a combination of demographic shocks, political centralization, economic evolution, and cultural shifts. Each factor interacted with the others, creating a complex web of pressures that transformed feudal structures into more modern systems. Understanding these dynamics offers valuable insights into how societies adapt and evolve in response to crises and innovation.

Artifacts and Power: Exploring the Political Implications of Design

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political feudalism is a system of governance characterized by decentralized power, where local lords or nobles hold authority over their territories in exchange for loyalty and service to a higher ruler, such as a king or monarch.

Political feudalism originated in medieval Europe as a response to the collapse of centralized Roman authority. It emerged as a way to organize society and protect communities in the absence of strong central governments.

Key features include hierarchical relationships between lords and vassals, land ownership tied to service obligations, decentralized political power, and a focus on local governance rather than centralized authority.

Political feudalism is based on inherited privilege, hierarchical relationships, and decentralized power, whereas modern democracy emphasizes equality, elected representation, and centralized governance with citizen participation.

While classical political feudalism no longer exists, some argue that its remnants can be seen in systems where power is concentrated in the hands of a few elites, or in regions with strong local autonomy and weak central governments.

![Mediaeval Feudalism by Stephenson, Carl 13th (thirteenth) Edition [Paperback(1956)]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/5144OBqpe-L._AC_UY218_.jpg)