Political enfranchisement refers to the process of granting individuals the right to participate in the political system, primarily through voting, but also encompassing broader civic engagement. It is a fundamental aspect of democratic societies, ensuring that citizens have a voice in decision-making processes that affect their lives. Historically, enfranchisement has been a struggle for marginalized groups, including women, racial minorities, and the working class, who have fought to secure their rights to vote and influence governance. Beyond voting, it involves access to political representation, the ability to run for office, and the freedom to engage in political discourse without discrimination. Achieving full enfranchisement is crucial for fostering inclusive democracies and addressing systemic inequalities.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Voting Rights Expansion: Ensuring all citizens, regardless of race, gender, or status, can vote

- Legal Barriers Removal: Eliminating laws that restrict access to political participation

- Civic Education: Empowering citizens through knowledge of political processes and rights

- Representation Equity: Promoting fair representation of marginalized groups in governance

- Accessibility Measures: Implementing tools like mail-in voting and polling place accessibility

Voting Rights Expansion: Ensuring all citizens, regardless of race, gender, or status, can vote

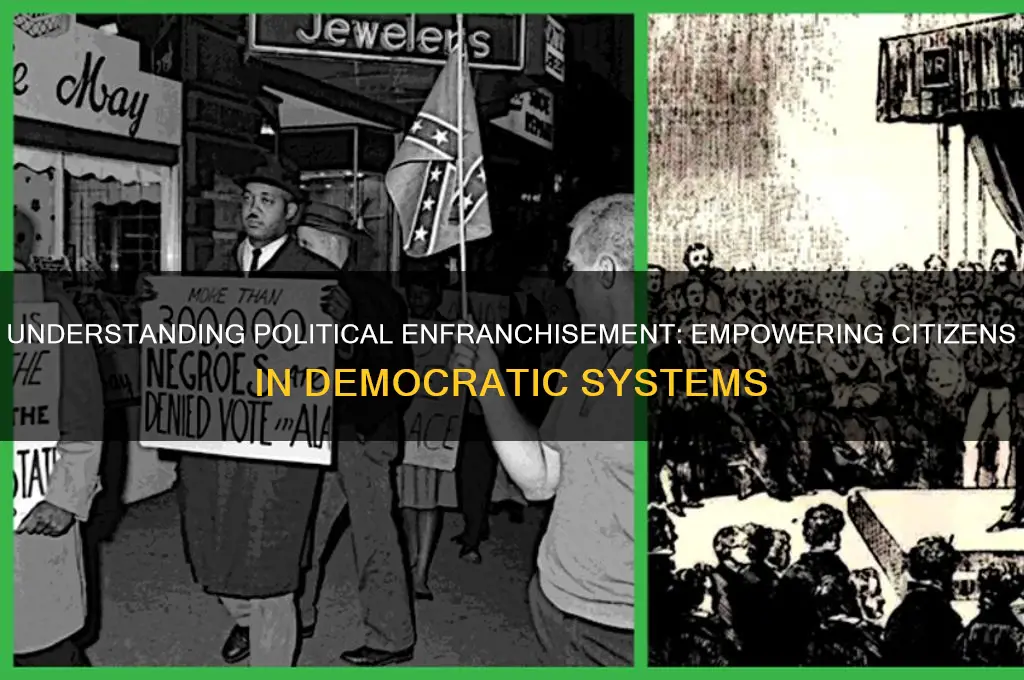

Political enfranchisement, at its core, is about dismantling barriers to participation in the democratic process. Voting rights expansion is a critical component of this, ensuring that every citizen, regardless of race, gender, or socioeconomic status, has an equal opportunity to cast a ballot. Historically, this has been a contentious issue, with marginalized groups often facing systemic obstacles to voting. For instance, the 15th Amendment in the U.S. (1870) aimed to grant voting rights to Black men, yet Jim Crow laws, poll taxes, and literacy tests effectively disenfranchised millions until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Similarly, women’s suffrage was not fully realized in the U.S. until the 19th Amendment in 1920, and Indigenous people were not guaranteed voting rights in all states until 1965. These milestones highlight the ongoing struggle to ensure universal suffrage.

Expanding voting rights requires a multi-faceted approach, addressing both legal and practical barriers. One key strategy is eliminating restrictive voter ID laws, which disproportionately affect low-income and minority voters. For example, studies show that strict ID requirements can reduce turnout by 2-3%, particularly among African American and Hispanic voters. Another critical step is restoring voting rights to formerly incarcerated individuals. In the U.S., 48 states restrict voting for people with felony convictions, with 11 states imposing lifetime bans unless explicitly restored. Florida’s 2018 Amendment 4, which restored voting rights to 1.4 million people with felony convictions, demonstrates the transformative potential of such reforms. However, subsequent legislation requiring full payment of fines and fees before voting undermines this progress, illustrating the need for vigilant advocacy.

Practical measures are equally important in ensuring voting accessibility. Expanding early voting periods, implementing automatic voter registration, and increasing the number of polling places in underserved communities can significantly boost participation. For instance, Oregon’s automatic voter registration system, introduced in 2016, has registered over 400,000 new voters, with turnout increasing by 4 percentage points in the 2020 election. Similarly, mail-in voting, which gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, has proven to be a vital tool for ensuring participation among elderly, disabled, and rural voters. However, these measures must be paired with robust safeguards against voter suppression tactics, such as purging voter rolls or spreading misinformation about election procedures.

The global perspective on voting rights expansion offers valuable lessons. New Zealand, for example, has one of the most inclusive voting systems, allowing citizens to register and vote on Election Day itself. This flexibility ensures that logistical barriers do not prevent participation. In contrast, countries like India, the world’s largest democracy, face challenges in reaching remote and marginalized populations, despite extensive efforts to set up polling stations in even the most inaccessible areas. These examples underscore the importance of tailoring solutions to local contexts while upholding the principle of universal suffrage.

Ultimately, voting rights expansion is not just a legal or logistical issue but a moral imperative. Democracy thrives when all voices are heard, and excluding any group undermines its legitimacy. Advocates must continue to push for reforms that address both overt and covert barriers to voting, ensuring that the right to vote is not just theoretical but practical for every citizen. This includes educating voters about their rights, challenging discriminatory laws in court, and holding elected officials accountable for protecting the integrity of the electoral process. By doing so, we move closer to a truly inclusive democracy where every vote counts, regardless of who casts it.

Is Bruce Springsteen Political? Exploring the Boss's Social Commentary

You may want to see also

Legal Barriers Removal: Eliminating laws that restrict access to political participation

Legal barriers to political participation have historically disenfranchised millions, often targeting marginalized groups such as racial minorities, women, and the poor. One of the most notorious examples is the Jim Crow laws in the United States, which used poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses to suppress Black voters. Similarly, women’s suffrage was restricted globally until the early 20th century, with laws explicitly barring them from voting or holding office. Removing these barriers requires a systematic approach: identify discriminatory laws, challenge them in courts or legislatures, and replace them with inclusive policies. For instance, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in the U.S. struck down many Jim Crow practices, demonstrating how legal reform can restore political rights.

To effectively eliminate restrictive laws, advocates must first audit existing legislation for discriminatory provisions. This involves scrutinizing voter ID requirements, residency rules, and criminal disenfranchisement laws that disproportionately affect specific groups. For example, strict voter ID laws often target low-income voters who may lack access to necessary documents. Once identified, these laws can be challenged through litigation, as seen in cases like *Shelby County v. Holder*, which highlighted the ongoing need for federal oversight in jurisdictions with a history of discrimination. Simultaneously, legislative action can repeal outdated laws, such as those barring formerly incarcerated individuals from voting, as several U.S. states have done in recent years.

A persuasive argument for removing legal barriers is their direct impact on democratic legitimacy. When laws exclude certain groups from political participation, the resulting policies often fail to represent their interests. For instance, Indigenous communities in countries like Canada and Australia have long been marginalized by laws that ignore their land rights and cultural autonomy. By eliminating these barriers, governments can foster more inclusive decision-making processes. Practical steps include lowering the voting age to 16, as proposed in some European countries, to engage younger citizens, and simplifying voter registration processes to increase turnout. These measures not only expand participation but also strengthen the democratic fabric.

Comparatively, countries that have successfully removed legal barriers offer valuable lessons. New Zealand, for example, has no voter registration deadlines, allowing citizens to register on election day, which boosts turnout. In contrast, some African nations, like South Africa, have made significant strides in post-apartheid reforms but still face challenges in rural voter access. A key takeaway is that legal reform must be accompanied by public education and infrastructure improvements to ensure meaningful participation. For instance, providing mobile polling stations in remote areas or offering multilingual voting materials can address logistical barriers that laws alone cannot fix.

Descriptively, the process of removing legal barriers often involves a tug-of-war between progress and resistance. In many cases, those benefiting from exclusionary laws fight to preserve them, as seen in recent debates over voting rights in the U.S. However, grassroots movements and international pressure can tip the scales toward reform. For example, the #LetUsVote campaign in the U.S. has mobilized public support for restoring voting rights to formerly incarcerated individuals. Ultimately, eliminating legal barriers is not just about changing laws but about transforming societies into more equitable and participatory democracies. This requires sustained effort, strategic advocacy, and a commitment to justice for all.

The Crucible's Political Underbelly: Power, Paranoia, and Social Control

You may want to see also

Civic Education: Empowering citizens through knowledge of political processes and rights

Political enfranchisement hinges on the ability to participate meaningfully in democratic processes, yet this participation is only as strong as the knowledge that underpins it. Civic education serves as the cornerstone for this empowerment, equipping citizens with the tools to navigate political systems, understand their rights, and engage effectively. Without it, the promise of enfranchisement remains hollow, leaving individuals vulnerable to manipulation or apathy.

Consider the mechanics of voting, a fundamental act of political participation. A citizen who understands the electoral process—from voter registration to ballot measures—is far more likely to cast an informed vote. For instance, in countries where civic education is integrated into school curricula, voter turnout among young adults tends to be higher. In Estonia, where digital literacy and civic education are prioritized, over 44% of voters participated in the 2019 parliamentary elections online, showcasing how knowledge translates into action. This example underscores the tangible impact of education on political engagement.

However, civic education is not merely about teaching procedural knowledge; it must also foster critical thinking and a sense of civic responsibility. Curriculum designers should emphasize real-world applications, such as analyzing campaign rhetoric, understanding the implications of policy proposals, and recognizing systemic barriers to participation. For example, in the United States, initiatives like the *We the People* program engage high school students in mock congressional hearings, encouraging them to dissect constitutional principles and apply them to contemporary issues. Such hands-on approaches bridge the gap between theory and practice, preparing citizens to advocate for their rights and hold leaders accountable.

Age-appropriate instruction is critical to the success of civic education. For younger students (ages 8–12), focus on foundational concepts like the role of government and the importance of community involvement. Middle schoolers (ages 13–15) can explore case studies of historical and current events, while high schoolers (ages 16–18) should delve into advanced topics like media literacy and the mechanics of advocacy. Tailoring content to developmental stages ensures that knowledge is retained and applied effectively.

Ultimately, civic education is not a one-time lesson but a lifelong process. It requires collaboration between educators, policymakers, and community organizations to create accessible, inclusive, and dynamic learning environments. By investing in this education, societies can transform passive citizens into active participants, ensuring that political enfranchisement is not just a right but a reality. The takeaway is clear: knowledge is power, and in the realm of politics, it is the key to meaningful participation.

How Political Decisions Shape the Global Economic Landscape

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Representation Equity: Promoting fair representation of marginalized groups in governance

Marginalized groups often face systemic barriers that limit their access to political power, perpetuating cycles of inequality. Representation equity seeks to dismantle these barriers by ensuring that governance structures reflect the diversity of the populations they serve. For instance, in countries with significant indigenous populations, such as New Zealand or Bolivia, reserved parliamentary seats for indigenous representatives have been established. These measures not only amplify indigenous voices but also ensure that policies address their unique needs. This approach underscores the importance of intentional design in political systems to counteract historical and structural exclusion.

Achieving representation equity requires more than symbolic gestures; it demands actionable strategies. One effective method is implementing quotas or affirmative action policies in legislative bodies. Rwanda, for example, has one of the highest percentages of women in parliament globally, largely due to constitutional quotas mandating at least 30% female representation. Similarly, in India, reserved seats for Scheduled Castes and Tribes have increased their political participation. However, quotas alone are insufficient. They must be paired with education, funding, and capacity-building programs to empower marginalized candidates to effectively serve once elected.

Critics often argue that representation equity undermines meritocracy, but this perspective overlooks the systemic advantages enjoyed by dominant groups. A comparative analysis reveals that diverse governance leads to better policy outcomes. For example, research shows that countries with higher gender parity in leadership are more likely to invest in social welfare programs. Similarly, LGBTQ+ representatives have been instrumental in advancing equality legislation in countries like Canada and the Netherlands. This evidence challenges the notion that equity measures compromise competence, instead demonstrating that inclusivity enhances governance.

To promote representation equity, stakeholders must adopt a multi-faceted approach. First, electoral systems should be reformed to encourage proportional representation, which naturally accommodates diverse voices. Second, political parties must prioritize recruiting and supporting candidates from marginalized backgrounds. Third, civil society organizations play a critical role in advocating for policy changes and holding leaders accountable. Finally, public awareness campaigns can shift cultural norms, fostering a society that values and demands equitable representation. By combining these strategies, we can move toward governance that truly serves all.

Decoding Democracy: A Beginner's Guide to Understanding Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

Accessibility Measures: Implementing tools like mail-in voting and polling place accessibility

Political enfranchisement hinges on dismantling barriers to participation, and accessibility measures like mail-in voting and polling place improvements are critical tools in this effort. Mail-in voting, for instance, eliminates the need for physical presence at polling stations, benefiting individuals with disabilities, the elderly, and those with caregiving responsibilities. During the 2020 U.S. elections, states with robust mail-in voting systems saw higher turnout among marginalized groups, demonstrating its effectiveness in broadening participation. However, success depends on secure, user-friendly systems and widespread public education to combat misinformation about fraud.

Polling place accessibility, on the other hand, requires a multi-faceted approach to ensure physical and logistical ease for all voters. This includes installing ramps, providing ballot templates in Braille, and ensuring voting machines are usable for individuals with motor or visual impairments. For example, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) mandates that polling places be free of architectural barriers, yet compliance remains inconsistent. A 2016 study found that 60% of polling places had at least one impediment, such as steep ramps or narrow doorways, highlighting the need for stricter enforcement and regular audits.

Implementing these measures involves both legislative action and community engagement. Governments must allocate funding for infrastructure upgrades and training for poll workers on accessibility protocols. Simultaneously, partnerships with disability advocacy groups can ensure solutions are tailored to real-world needs. For instance, the UK’s Electoral Commission collaborates with organizations like Scope to design accessible voting materials and procedures, setting a model for inclusive election administration.

Critics argue that mail-in voting could lead to fraud or logistical challenges, but evidence suggests these risks are minimal when proper safeguards are in place. Similarly, the cost of retrofitting polling places is often cited as a barrier, yet the long-term benefits of increased participation far outweigh the initial investment. By prioritizing accessibility, societies not only fulfill democratic ideals but also strengthen the legitimacy of their electoral processes.

Ultimately, accessibility measures are not just legal or logistical fixes—they are affirmations of every citizen’s right to participate in governance. Mail-in voting and polling place improvements are not one-size-fits-all solutions but require continuous adaptation to address evolving needs. As democracies strive for inclusivity, these tools serve as both a foundation and a benchmark for measuring progress toward true political enfranchisement.

Finland's Political Stability: A Model of Consistency and Resilience

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political enfranchisement refers to the granting of the right to vote and participate in the political process to a group of people who were previously excluded.

Historically, groups such as women, racial minorities, and people without property have been disenfranchised, often due to discriminatory laws or societal norms.

Political enfranchisement strengthens democracy by ensuring broader representation, inclusivity, and equal participation in the decision-making process.

Examples include the 19th Amendment in the U.S. granting women the right to vote (1920), the Voting Rights Act of 1965 combating racial discrimination, and lowering the voting age to 18 in many countries.

Yes, political enfranchisement can be reversed through restrictive laws, voter suppression tactics, or changes in policy that limit access to voting rights.