Political conflict theory is a framework within political science and sociology that examines how power dynamics, inequality, and competing interests shape political systems and societal structures. Rooted in the works of thinkers like Karl Marx and Max Weber, it posits that politics is inherently conflictual, driven by struggles between social groups over resources, ideology, and control. Unlike consensus theories, which emphasize cooperation and shared values, conflict theory highlights how dominant classes or elites maintain power through coercion, manipulation, or institutional mechanisms, often at the expense of marginalized groups. This perspective is particularly useful for analyzing issues such as class struggle, racial inequality, and state repression, offering insights into the ways in which political systems both reflect and perpetuate systemic conflicts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Focus on Power Dynamics | Emphasizes the struggle for power, resources, and control within society. |

| Class Conflict | Highlights conflicts between social classes (e.g., bourgeoisie vs. proletariat). |

| Inequality as a Driver | Views inequality as the root cause of political and social conflicts. |

| Critique of Capitalism | Often critiques capitalist systems for perpetuating exploitation and inequality. |

| Role of the State | Sees the state as a tool of the dominant class to maintain power. |

| Historical Materialism | Grounds analysis in material conditions and economic structures. |

| Revolutionary Change | Advocates for systemic change or revolution to address inequalities. |

| Conflict as Inherent | Considers conflict as a natural and inevitable part of political systems. |

| Ideology as a Tool | Views dominant ideologies as mechanisms to justify and maintain power. |

| Global Perspective | Analyzes conflicts across national and international scales. |

| Intersectionality | Acknowledges overlapping systems of oppression (e.g., race, gender, class). |

| Empirical and Normative | Combines empirical analysis with normative critiques of existing systems. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Conflict Theory: Marxist roots, class struggle, power dynamics, and societal inequality as core concepts

- Key Thinkers: Contributions from Marx, Engels, Gramsci, and contemporary theorists like Wright and Collins

- Power and Domination: Analysis of how elites maintain control through institutions, ideology, and coercion

- Class and Stratification: Role of economic systems in creating and perpetuating social and political divisions

- Applications in Politics: Conflict theory’s use in understanding revolutions, protests, and global power structures

Origins of Conflict Theory: Marxist roots, class struggle, power dynamics, and societal inequality as core concepts

Political conflict theory finds its deepest roots in Marxist philosophy, which posits that society is inherently structured around class struggle. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in their seminal work *The Communist Manifesto* (1848), argued that history is a series of conflicts between opposing classes—primarily the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) and the proletariat (the working class). This framework is not merely descriptive but prescriptive, urging a revolutionary overthrow of capitalist systems to achieve a classless society. Marx’s analysis of capitalism as a system of exploitation, where the proletariat’s labor is extracted for the bourgeoisie’s profit, remains a cornerstone of conflict theory. This foundational idea underscores how economic disparities are not accidental but systemic, designed to maintain the dominance of the ruling class.

To understand conflict theory’s mechanics, consider its focus on power dynamics. Unlike functionalist theories, which view society as a harmonious whole, conflict theory highlights how power is unequally distributed and actively contested. For instance, in capitalist societies, political institutions often serve the interests of the wealthy, perpetuating policies that widen the wealth gap. This is evident in tax structures favoring corporations or labor laws that suppress workers’ rights. The takeaway here is clear: power is not neutral; it is a tool wielded by the dominant class to maintain control. Analyzing these dynamics requires scrutinizing not just economic systems but also the cultural and political mechanisms that reinforce inequality.

A practical example of conflict theory in action is the global labor movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Workers, inspired by Marxist ideas, organized strikes and unions to demand better wages, safer conditions, and shorter hours. These struggles were not merely about economic gains but were fundamentally challenges to the power of industrial capitalists. The Haymarket Affair in Chicago (1886) and the Russian Revolution (1917) are emblematic of how class struggle can escalate into political upheaval. Such historical moments illustrate the theory’s core assertion: societal change often emerges from conflict, not consensus.

However, applying conflict theory requires caution. While its critique of inequality is powerful, it risks oversimplifying complex social issues by reducing them solely to class struggle. For instance, intersectional analyses highlight how race, gender, and ethnicity intersect with class, creating layered forms of oppression that Marxist frameworks alone cannot fully capture. Practitioners of conflict theory must therefore integrate these perspectives to avoid reductive interpretations. A balanced approach acknowledges that while class is a primary driver of conflict, it is not the only one.

In conclusion, the origins of conflict theory in Marxist thought provide a robust lens for understanding societal inequality and power dynamics. By focusing on class struggle, it offers a critical tool for dissecting how systems perpetuate dominance and exploitation. Yet, its utility is maximized when complemented by broader analyses of identity and intersectionality. For those seeking to apply conflict theory, the key lies in recognizing its strengths while remaining open to its limitations, ensuring a more nuanced understanding of political and social conflicts.

Mastering Political Theory: Essential Strategies for Critical Reading and Analysis

You may want to see also

Key Thinkers: Contributions from Marx, Engels, Gramsci, and contemporary theorists like Wright and Collins

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels laid the foundational framework for political conflict theory, arguing that society is inherently structured around class struggle. Their seminal work, *The Communist Manifesto* (1848), posits that the capitalist system perpetuates inequality by dividing society into two primary classes: the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) and the proletariat (wage laborers). Marx and Engels contended that this antagonistic relationship would inevitably lead to revolution, culminating in a classless society. Their materialist analysis emphasizes economic structures as the root of political conflict, a perspective that remains central to conflict theory today. For practitioners seeking to understand systemic inequality, Marx and Engels’ work offers a diagnostic tool: examine who controls resources and how this control shapes power dynamics.

Antonio Gramsci expanded on Marxist thought by introducing the concept of cultural hegemony, which explains how dominant classes maintain power not just through coercion but also through ideological control. In his *Prison Notebooks* (written 1929–1935), Gramsci argued that the ruling class disseminates its values and norms through institutions like education, media, and religion, creating a consensus that their dominance is natural and inevitable. This insight is particularly relevant for contemporary analysts studying how political narratives are shaped. To counter hegemonic control, Gramsci proposed the creation of counter-hegemonic movements that challenge dominant ideologies. Activists and scholars can apply this by identifying and amplifying marginalized voices to disrupt established power structures.

Contemporary theorists like Erik Olin Wright and Patricia Hill Collins have built upon these classical foundations, adapting conflict theory to address modern complexities. Wright’s work on class analysis introduces the concept of "contradictory class locations," acknowledging that individuals may occupy multiple class positions simultaneously, which complicates traditional Marxist binaries. His *Classes* (1997) provides a nuanced framework for understanding class dynamics in post-industrial societies. Meanwhile, Collins, in *Black Feminist Thought* (1990), integrates race, gender, and class into conflict theory, highlighting how intersecting systems of oppression create unique experiences of marginalization. Her intersectional approach is essential for practitioners addressing multifaceted inequalities, offering a more inclusive lens than earlier theories.

To apply these contributions effectively, consider a three-step approach: first, use Marx and Engels’ materialist analysis to map economic power structures; second, employ Gramsci’s hegemony framework to uncover ideological control mechanisms; and finally, incorporate Wright and Collins’ insights to account for intersectional complexities. This layered methodology ensures a comprehensive understanding of political conflict, enabling more targeted interventions. For instance, a policy analyst might use this approach to critique how economic policies disproportionately benefit certain groups while perpetuating cultural narratives that justify inequality. By synthesizing these thinkers’ ideas, practitioners can develop strategies that address both the material and ideological dimensions of conflict.

Nationalism as a Political Ideology: Unraveling Its Core Principles and Impact

You may want to see also

Power and Domination: Analysis of how elites maintain control through institutions, ideology, and coercion

Elites maintain political control through a triad of mechanisms: institutions, ideology, and coercion. Institutions, such as governments, legal systems, and economic structures, are designed to formalize and legitimize their dominance. For example, electoral systems often favor established parties, while corporate lobbying ensures policies align with elite interests. These institutions create a framework where power appears neutral and bureaucratic, masking its concentration in the hands of a few.

Ideology serves as the invisible glue that binds societies to elite rule. By promoting narratives of meritocracy, nationalism, or free-market superiority, elites shape public perception to justify their privilege. Consider how the "American Dream" narrative perpetuates the idea that anyone can succeed through hard work, diverting attention from systemic barriers that favor the wealthy. This ideological control is reinforced through education, media, and cultural institutions, making dissent seem irrational or unpatriotic.

Coercion, the bluntest tool, is employed when institutions and ideology fail. This includes both overt violence, such as police crackdowns on protests, and subtler forms like surveillance or economic sanctions. For instance, during labor strikes, elites often use legal injunctions or police force to suppress worker demands, ensuring their economic interests remain undisturbed. Coercion is a last resort but a potent reminder of who holds the ultimate power.

To challenge elite domination, one must first understand these mechanisms. Start by critically examining institutional structures: Who benefits from current policies? How can marginalized groups gain representation? Next, deconstruct dominant ideologies: Question narratives that normalize inequality and seek alternative perspectives. Finally, recognize coercion in its various forms and build solidarity to resist it. Practical steps include supporting grassroots movements, engaging in media literacy, and advocating for transparent governance. By dismantling these pillars of control, one can begin to shift the balance of power toward a more equitable society.

Polite Ways to Remind Your Teacher: Effective Communication Tips for Students

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Class and Stratification: Role of economic systems in creating and perpetuating social and political divisions

Economic systems are not neutral frameworks for resource distribution; they are engines of stratification, systematically sorting populations into hierarchical classes with unequal access to wealth, power, and opportunity. Capitalism, for instance, relies on a wage-labor system where the ownership of capital concentrates in the hands of a minority, while the majority must sell their labor to survive. This structural inequality is not incidental but inherent: the profit motive incentivizes exploitation, as businesses maximize returns by minimizing labor costs, often through low wages, precarious employment, and resistance to unionization. The result is a self-perpetuating divide between the capitalist class and the working class, with the former wielding disproportionate political influence to protect their economic interests.

Consider the empirical evidence: in the United States, the top 1% of households own nearly 35% of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 50% hold just 2%. This disparity is not merely a reflection of individual merit or effort but a consequence of systemic mechanisms like tax policies favoring the wealthy, corporate subsidies, and the erosion of social safety nets. These policies are not accidental; they are actively shaped by political institutions dominated by elites who benefit from the status quo. For example, lobbying efforts by corporations and wealthy individuals often result in legislation that undermines labor rights, weakens environmental protections, and reduces corporate taxes, further entrenching class divisions.

To dismantle these divisions, a multi-pronged approach is necessary. First, progressive taxation must be implemented to redistribute wealth and fund public services that benefit all citizens, such as universal healthcare and education. Second, labor laws need to be strengthened to protect workers’ rights, including higher minimum wages, guaranteed sick leave, and the right to collective bargaining. Third, democratic reforms are essential to reduce the influence of money in politics, such as campaign finance regulations and stricter lobbying laws. These steps, while challenging, are not utopian; countries like Sweden and Denmark demonstrate that more equitable economic systems are achievable through deliberate policy choices.

However, caution is warranted. Simply redistributing wealth without addressing the underlying structures of capitalism risks treating symptoms rather than causes. For instance, while universal basic income (UBI) has gained traction as a potential solution to poverty, it could inadvertently subsidize low-wage employers, allowing them to pay workers even less. Similarly, without robust antitrust enforcement, wealth redistribution efforts may be undermined by the continued concentration of economic power in the hands of a few corporations. Thus, any strategy to reduce class stratification must confront the systemic roots of inequality, not just its manifestations.

Ultimately, the role of economic systems in creating and perpetuating social and political divisions is undeniable. They are not passive backdrops to human activity but active forces shaping who has power, who struggles, and who is left behind. Recognizing this reality is the first step toward challenging it. By combining empirical analysis, policy innovation, and a commitment to structural change, it is possible to build economic systems that serve the many, not just the few. The alternative is a world where class divisions deepen, democracy erodes, and the promise of equality remains an unattainable dream.

Understanding Political Surveys: Methods, Accuracy, and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

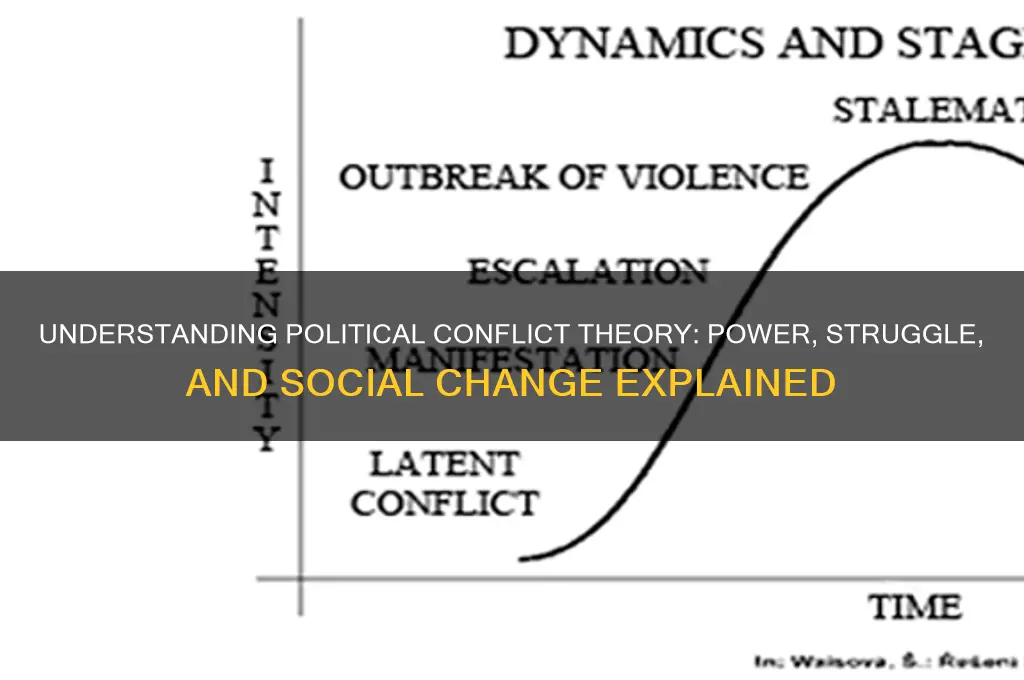

Applications in Politics: Conflict theory’s use in understanding revolutions, protests, and global power structures

Political conflict theory posits that society is inherently structured around power struggles between dominant and subordinate groups. This framework is particularly illuminating when applied to revolutions, protests, and global power structures, offering a lens to dissect the forces driving political upheaval and systemic inequality. By examining these phenomena through the prism of conflict theory, we can identify recurring patterns, such as the exploitation of resources, the suppression of dissent, and the mobilization of marginalized groups. For instance, the French Revolution can be understood as a direct response to the aristocracy’s monopolization of wealth and political power, illustrating how conflict theory explains the eruption of mass movements against oppressive structures.

To apply conflict theory in understanding protests, consider its emphasis on the role of ideology in maintaining or challenging the status quo. Protests often emerge when the ideological justifications for inequality—such as meritocracy or national unity—are exposed as hollow. The Black Lives Matter movement, for example, not only confronts police brutality but also dismantles the narrative of racial equality in societies built on systemic racism. Practitioners of political analysis can use conflict theory to trace how protests evolve from localized grievances to broader challenges against institutional power, identifying key tipping points where public consciousness shifts from acceptance to resistance.

Revolutions, as the most extreme manifestation of political conflict, require a deeper analysis of the material conditions that precipitate them. Conflict theory highlights the importance of economic disparities, political exclusion, and cultural alienation in fueling revolutionary sentiment. The Arab Spring, for instance, was not merely a series of spontaneous uprisings but a culmination of decades of economic exploitation, authoritarian rule, and youth disenfranchisement. Analysts can employ conflict theory to map the interplay between these factors, predicting where similar conditions might lead to future revolutions and advising policymakers on mitigating risks through equitable reforms.

On a global scale, conflict theory reveals how power structures perpetuate inequality between nations, often through mechanisms like neocolonialism, resource extraction, and geopolitical dominance. The relationship between the Global North and South exemplifies this dynamic, with wealthier nations maintaining control over poorer ones through debt, trade policies, and military interventions. Activists and scholars can use conflict theory to advocate for systemic changes, such as debt forgiveness or fair trade agreements, by exposing the exploitative foundations of global power structures. This approach not only critiques existing systems but also offers a roadmap for fostering more equitable international relations.

Finally, conflict theory provides practical tools for strategizing political action. Organizers can leverage its insights to build coalitions across diverse groups, identifying shared interests in challenging dominant power structures. For example, labor unions and environmental activists might unite against corporate exploitation, recognizing that both face oppression under capitalist systems. By framing struggles as part of a broader conflict between oppressors and oppressed, movements can amplify their impact and sustain momentum. In essence, conflict theory is not just a diagnostic tool but a strategic guide for those seeking to transform politics from the ground up.

Muse's Political Edge: Decoding Their Lyrics and Social Stance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political conflict theory is a framework that examines how power struggles, inequality, and competing interests shape political systems, policies, and societal structures. It emphasizes the role of conflict between social groups, such as classes, races, or genders, in driving political change and maintaining dominance.

Key contributors include Karl Marx, who analyzed class conflict as the engine of historical change, and later scholars like Max Weber, who expanded on the role of power and conflict in social and political systems. Contemporary theorists like Michel Foucault and feminist scholars have further developed the theory to include issues of gender, race, and discourse.

While consensus theory focuses on shared values, cooperation, and stability as the foundations of society, political conflict theory highlights division, competition, and struggle as central to political dynamics. It argues that conflict, rather than harmony, is the primary force shaping political outcomes.

Political conflict theory is applied to analyze issues like income inequality, racial injustice, labor disputes, and global power imbalances. It helps explain phenomena such as revolutions, social movements, and policy resistance, offering insights into how marginalized groups challenge dominant power structures.