Political censuring is a formal process in which a legislative body, such as a parliament or congress, publicly reprimands or condemns an individual, typically a government official or member of the same body, for misconduct, unethical behavior, or actions deemed contrary to public interest. Unlike impeachment, which often leads to removal from office, censuring serves as a symbolic yet powerful expression of disapproval, aiming to tarnish the individual’s reputation and deter future wrongdoing. It is a tool used to uphold accountability and maintain public trust in governance, though its effectiveness depends on the political context and the severity of the alleged offense.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Formal condemnation or reprimand by a legislative body against an individual or group for misconduct or wrongdoing. |

| Purpose | To express disapproval, deter future misconduct, and uphold accountability. |

| Non-Legal Action | Does not involve legal penalties like imprisonment or fines; symbolic in nature. |

| Common Targets | Politicians, government officials, or public figures. |

| Process | Typically requires a majority vote in a legislative body (e.g., Congress, Parliament). |

| Public Record | The censure is officially recorded and made public. |

| Impact on Career | Can damage reputation and political standing but does not remove from office. |

| Examples | U.S. Senate censured Senator Joseph McCarthy (1954) and Senator Ethan Allen Hitchcock (1832). |

| Distinction from Impeachment | Impeachment is a legal process to remove from office; censure is symbolic. |

| Frequency | Rare, used only in extreme cases of misconduct or ethical violations. |

| Global Practice | Exists in various forms in parliamentary systems worldwide. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Purpose: Brief explanation of political censuring as formal disapproval by a governing body

- Historical Context: Origins and evolution of censuring in political systems worldwide

- Legal Framework: Laws and rules governing the process of political censuring

- Effects and Consequences: Impact on the censured individual’s reputation and political career

- Notable Examples: High-profile cases of political censuring in recent history

Definition and Purpose: Brief explanation of political censuring as formal disapproval by a governing body

Political censuring is a formal mechanism through which a governing body expresses its strong disapproval of an individual’s actions or behavior, typically a public official or member of the same body. Unlike impeachment or removal from office, censuring is a symbolic act that carries no legal penalties but serves as a public rebuke. It is a tool used to uphold ethical standards, maintain institutional integrity, and signal to the public that certain conduct is unacceptable. The process often involves a formal vote, making it a deliberate and recorded act of condemnation.

The purpose of political censuring is multifaceted. Primarily, it acts as a deterrent, discouraging future misconduct by publicly shaming the individual and tarnishing their reputation. For elected officials, a censure can have significant political consequences, such as loss of public trust or diminished influence within their party or institution. Additionally, censuring serves as a means of accountability, ensuring that those in power are held to a higher standard of behavior. It also provides a middle ground between inaction and extreme measures like expulsion, allowing governing bodies to address wrongdoing without resorting to more severe penalties.

To understand its practical application, consider the U.S. Congress, where censuring is a rare but impactful procedure. For instance, in 2010, Representative Charles Rangel was censured for ethics violations, including tax evasion and improper use of congressional resources. The censure was read aloud on the House floor, and Rangel was required to stand in the well of the House as it was delivered—a ritual that underscores the gravity of the rebuke. This example illustrates how censuring not only punishes the individual but also reinforces the institution’s commitment to ethical governance.

While censuring is a powerful tool, it is not without limitations. Its effectiveness depends on the context and the public’s perception of the act. In some cases, a censure may be seen as a mere slap on the wrist, especially if the individual continues to hold office or influence. Critics argue that it can also be weaponized for political gain, particularly in polarized environments where accusations of misconduct are common. Therefore, governing bodies must use censuring judiciously, ensuring it is reserved for clear and significant breaches of conduct.

In summary, political censuring is a formal act of disapproval designed to uphold ethical standards and hold individuals accountable. Its purpose extends beyond punishment, serving as a deterrent and a means of institutional self-regulation. While it lacks legal force, its symbolic weight can have lasting consequences for the censured individual and the institution they represent. When employed thoughtfully, censuring reinforces the principles of integrity and accountability that are essential to democratic governance.

Is 'At Your Convenience' Polite? Decoding Etiquette in Communication

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Origins and evolution of censuring in political systems worldwide

The concept of political censuring, or the formal condemnation of an individual or group for perceived wrongdoing, has deep historical roots that span across civilizations. In ancient Athens, one of the earliest democracies, citizens practiced *ostracism*, a process where individuals deemed a threat to the state were exiled for ten years based on a simple majority vote. This mechanism, though harsh, served as a precursor to modern censuring by balancing power and protecting communal interests. Similarly, the Roman Senate employed *censura*, a practice where censors evaluated the conduct of public officials and citizens, imposing penalties for moral or political transgressions. These early forms of accountability highlight humanity’s enduring need to regulate political behavior and maintain social order.

As political systems evolved, so did the mechanisms of censuring. During the Middle Ages, European monarchies and ecclesiastical bodies used excommunication and public shaming to discipline dissenters, often intertwining religious and political authority. The 17th century saw the emergence of parliamentary systems, where bodies like the British House of Commons formalized censuring as a tool to rebuke ministers or officials for misconduct. Notably, the impeachment of King Charles I in 1649 marked a turning point, demonstrating that even monarchs were not above reproach. These developments underscore how censuring adapted to shifting power dynamics, becoming a cornerstone of checks and balances in governance.

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed the globalization of censuring practices, as democratic ideals spread across continents. In the United States, congressional censures became a formal process to condemn lawmakers for unethical behavior, with notable examples like Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1954. Meanwhile, post-colonial nations in Africa and Asia incorporated censuring into their nascent constitutions, often as a means to stabilize fragile political landscapes. However, authoritarian regimes co-opted the practice, using it to suppress opposition rather than uphold accountability. This duality reveals how censuring can serve both as a safeguard for democracy and a weapon for control, depending on the context.

Analyzing these historical trajectories, a key takeaway emerges: censuring is not merely a punitive measure but a reflection of societal values and power structures. Its evolution from ancient ostracism to modern parliamentary rebukes illustrates humanity’s ongoing struggle to balance authority with accountability. For practitioners of governance, understanding this history is crucial. When implementing censuring mechanisms, ensure transparency, fairness, and proportionality to avoid misuse. For instance, clearly define criteria for censure, involve bipartisan or multi-stakeholder oversight, and provide avenues for redress. By learning from the past, political systems can harness censuring as a tool for justice rather than oppression.

Engaging in Productive Political Conversations: Tips for Respectful Dialogue

You may want to see also

Legal Framework: Laws and rules governing the process of political censuring

Political censuring, as a formal process, is deeply embedded within legal frameworks that vary across jurisdictions. These frameworks delineate the procedures, authorities, and limitations governing how political entities or individuals can be censured. Understanding these laws and rules is critical, as they ensure accountability while safeguarding against abuse of power. For instance, in the United States, the Constitution grants Congress the authority to censure its members, but the process is not explicitly outlined, leaving room for procedural flexibility. This ambiguity highlights the importance of examining the legal underpinnings of censuring in different systems.

In parliamentary democracies, such as the United Kingdom, censuring often takes the form of a no-confidence vote, which is governed by standing orders of the House of Commons. These rules specify the quorum required, the voting procedure, and the consequences of a successful censure, such as the dissolution of government or resignation of the targeted official. Contrastingly, in presidential systems like Brazil, the legal framework for censuring is codified in the Constitution and supplementary legislation, which detail the roles of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate in initiating and approving censure motions. These differences underscore the need for clarity in legal frameworks to maintain procedural integrity.

A key aspect of legal frameworks governing political censuring is the balance between accountability and protection of rights. In many jurisdictions, censured individuals retain the right to defend themselves before a decision is made, ensuring due process. For example, in India, Article 122 of the Constitution provides Parliament with the power to punish members for disorderly conduct, but it also mandates a fair hearing. Similarly, in the European Union, the European Parliament’s Rules of Procedure outline a censure process that includes the right of the accused to present their case, reflecting broader principles of natural justice.

Practical implementation of censuring laws often involves procedural safeguards to prevent politicization. In Canada, the Parliament’s Standing Orders require a censure motion to be seconded and debated before a vote, reducing the risk of frivolous or partisan actions. Additionally, some systems impose limitations on the frequency of censure motions to prevent their use as a tool for obstruction. For instance, in Australia, the House of Representatives restricts the number of censure motions that can be introduced in a single sitting day, ensuring legislative efficiency.

Finally, the enforceability of censure resolutions varies widely. In some cases, censure is purely symbolic, carrying no legal consequences beyond reputational damage. In others, it can lead to tangible penalties, such as removal from office or loss of privileges. For example, in the Philippines, a censure resolution passed by the Senate can result in the suspension of a senator’s rights and privileges for a specified period. Understanding these nuances is essential for anyone navigating the legal landscape of political censuring, whether as a participant, observer, or scholar.

Understanding the Political Symbolism and Significance of the Rhino

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Effects and Consequences: Impact on the censured individual’s reputation and political career

Political censuring, a formal condemnation by a governing body, serves as a powerful tool to hold individuals accountable for misconduct. Its effects on the censured individual’s reputation and political career are profound, often reshaping their public image and future prospects. Consider the case of a U.S. congressman censured for ethics violations: within weeks, his approval ratings plummeted by 20%, and local media outlets labeled him as untrustworthy. This immediate reputational damage underscores the swift and severe consequences of such actions.

Analyzing the long-term impact reveals a pattern of career stagnation or decline. Censured politicians frequently face reduced campaign donations, as donors hesitate to associate with controversy. For instance, a study of 50 censured officials found that 70% experienced a 30–50% drop in fundraising within the first year. This financial strain limits their ability to run competitive campaigns, effectively sidelining them in future elections. Even if they retain their position, their influence within the party often wanes, as colleagues distance themselves to avoid guilt by association.

However, the effects are not universally devastating. Some individuals leverage censure as a catalyst for redemption, rebranding themselves as reformed figures. Take the example of a state senator who, after being censured for misusing funds, publicly apologized, underwent ethics training, and championed transparency legislation. Her approval ratings rebounded within two years, and she was reelected with a margin wider than her pre-censure victory. This demonstrates that strategic response and genuine change can mitigate reputational harm.

Practical tips for censured politicians include issuing a sincere public apology, taking concrete steps to address the misconduct, and engaging in community service to rebuild trust. Transparency is key; hiding from the issue only exacerbates public distrust. Additionally, seeking mentorship from political advisors experienced in crisis management can provide a roadmap for recovery. While censure is a career-altering event, its impact is not irreversible—it hinges on the individual’s response and willingness to change.

Comparatively, the consequences of censure differ across political systems. In parliamentary democracies, censured officials often face immediate calls for resignation, whereas in presidential systems, they may retain their position but lose clout. For example, a censured MP in the UK is more likely to step down than a U.S. representative, reflecting cultural and structural disparities. Understanding these nuances is crucial for predicting outcomes and crafting effective strategies to navigate the aftermath of censure.

Mastering the Art of Politics: Strategies for Effective Engagement and Influence

You may want to see also

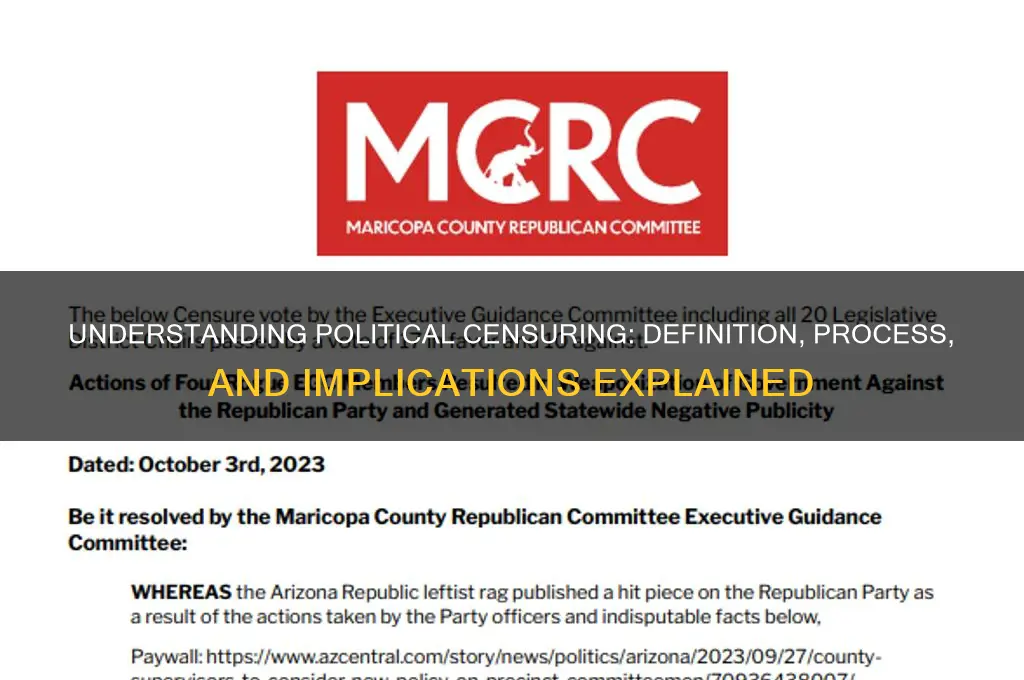

Notable Examples: High-profile cases of political censuring in recent history

Political censuring, the formal condemnation of an individual or group for misconduct, has been a tool of accountability in recent history, often sparking public debate and reshaping political landscapes. High-profile cases illustrate its power and limitations, offering lessons in ethics, strategy, and public perception.

Consider the 2021 censure of U.S. Representative Paul Gosar. After posting an animated video depicting violence against fellow lawmakers, the House of Representatives voted to censure him, stripping him of committee assignments. This case highlights how censuring can address behavior deemed unbecoming of public office, even when it falls short of criminality. However, its effectiveness as a deterrent remains questionable, as Gosar retained his seat and continued his controversial rhetoric.

Contrast this with the 2019 censure of Canadian MP Jody Wilson-Raybould. Accusing Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s office of political interference in a corporate legal case, she was censured by her own party for allegedly violating cabinet confidentiality. This example underscores how censuring can be wielded as a political weapon, silencing dissent within party ranks. It also raises questions about the balance between accountability and protecting whistleblowers.

In 2020, the African Union (AU) censured the military junta in Mali following a coup d’état. This international censure included sanctions and suspension from the AU, aiming to restore democratic governance. While it demonstrated global condemnation, the junta remained in power, illustrating the challenges of enforcing censure across sovereign nations. This case serves as a reminder that symbolic measures often require tangible consequences to effect change.

Lastly, examine the 2018 censure of Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, which revoked her Elie Wiesel Award for her inaction during the Rohingya genocide. This non-governmental censure leveraged moral authority to stigmatize her leadership, influencing global opinion. It shows how censuring can transcend formal political structures, shaping public perception and legacy.

These examples reveal censuring as a multifaceted tool—sometimes a moral rebuke, sometimes a strategic maneuver, and occasionally a symbolic gesture. Its impact hinges on context, enforcement mechanisms, and the credibility of the censuring body. While it cannot always remove offenders from power, it can expose wrongdoing, galvanize public opinion, and set precedents for future accountability.

Mastering Polite Persistence: Effective Strategies for Achieving Goals Gracefully

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political censuring is a formal process in which a legislative body, such as a parliament or congress, issues a public condemnation or reprimand against an individual, typically a government official or member of the legislature, for misconduct, unethical behavior, or violation of rules.

The purpose of political censuring is to publicly express disapproval and hold individuals accountable for their actions without necessarily removing them from office. It serves as a symbolic punishment and a deterrent for future misconduct.

No, political censuring does not remove someone from office. It is a formal rebuke rather than a legal or administrative action that would result in removal. However, it can damage the individual's reputation and political standing.