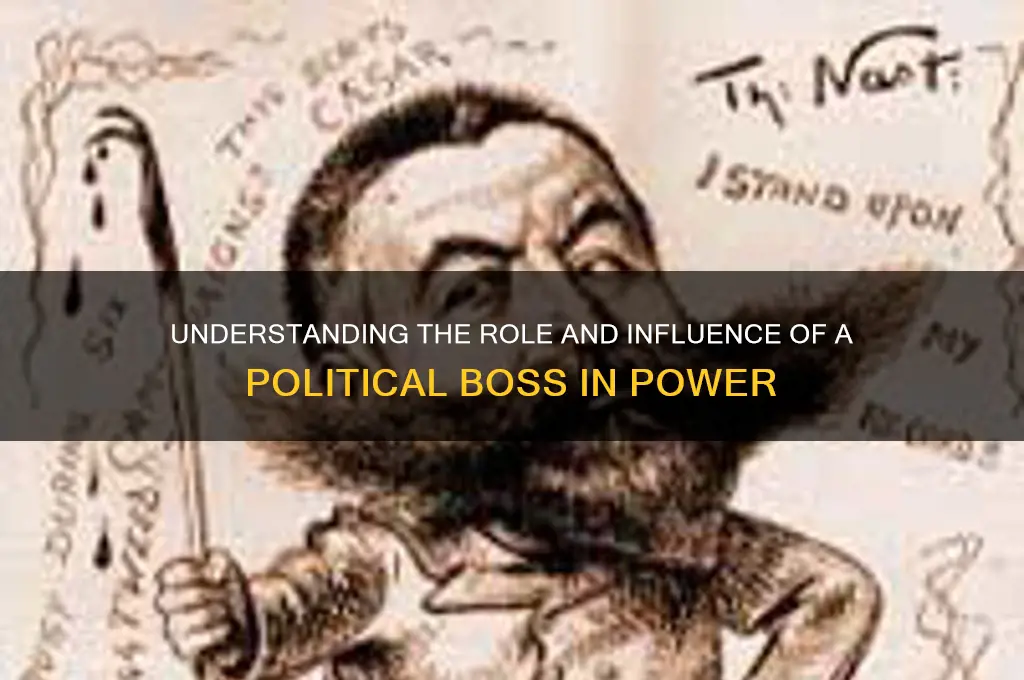

A political boss is a powerful, often unelected figure who wields significant influence within a political party or organization, typically at the local or regional level. These individuals operate behind the scenes, controlling party resources, directing patronage, and orchestrating political appointments to maintain their grip on power. Emerging predominantly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States, political bosses were central to machine politics, using their networks to mobilize voters, secure electoral victories, and advance their own interests. While often associated with corruption and cronyism, they also played a role in delivering services to marginalized communities and consolidating party loyalty. Understanding the role of a political boss sheds light on the dynamics of power, patronage, and influence in political systems, both historically and in contemporary contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political boss is a powerful figure who controls a political party or organization, often through patronage, influence, and strategic decision-making. |

| Role | Acts as a kingmaker, influencing elections, appointments, and policy decisions. |

| Power Base | Relies on a network of supporters, often through patronage (jobs, favors, resources). |

| Influence | Wields significant control over party members, candidates, and elected officials. |

| Decision-Making | Makes key decisions behind the scenes, often without holding formal office. |

| Patronage System | Distributes rewards (jobs, contracts, favors) to maintain loyalty and control. |

| Local vs. National | Can operate at local, state, or national levels, depending on their reach. |

| Historical Context | Prominent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (e.g., Tammany Hall in the U.S.), but still exists in modern politics. |

| Modern Examples | Found in political machines, party hierarchies, or as influential donors/lobbyists. |

| Criticism | Often associated with corruption, nepotism, and undermining democratic processes. |

| Legitimacy | May operate within or outside legal frameworks, depending on the political system. |

| Key Skills | Strategic thinking, networking, negotiation, and resource management. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Role: A political boss controls party resources, influences decisions, and wields power behind the scenes

- Historical Context: Emerged in 19th-century U.S., linked to machine politics and urban party systems

- Power Sources: Derived from patronage, voter mobilization, and control over local institutions

- Criticisms: Accused of corruption, nepotism, and undermining democratic processes for personal gain

- Modern Relevance: Still exists in weaker forms, adapting to changes in political structures and laws

Definition and Role: A political boss controls party resources, influences decisions, and wields power behind the scenes

A political boss is the invisible hand that shapes the machinery of power, often unseen but always felt. This figure operates in the shadows, controlling the levers of party resources—funds, endorsements, and organizational networks—to dictate the direction of political movements. Their influence is not wielded through public office but through strategic manipulation of these assets, ensuring their preferred candidates rise and their agendas prevail. This behind-the-scenes role allows them to maintain power without the constraints of public scrutiny or electoral accountability.

Consider the historical example of Boss Tweed, the notorious Tammany Hall leader in 19th-century New York. Tweed mastered the art of resource control, funneling party funds into patronage jobs and kickbacks while securing political loyalty through favors and threats. His ability to influence decisions—from local elections to state legislation—demonstrated how a political boss can dominate a system without ever holding formal office. Tweed’s downfall, however, underscores a cautionary tale: unchecked power in the shadows often leads to corruption and public backlash.

To understand the role of a political boss, imagine a chessboard where the boss is the player, not the pieces. They strategically allocate resources—campaign funds, media access, and grassroots support—to advance their interests. For instance, in modern politics, bosses might control donor networks, directing millions to candidates who align with their vision. This influence extends to decision-making, where bosses quietly shape policy agendas, broker deals, and even dictate legislative priorities. Their power lies in their ability to operate unseen, pulling strings without leaving fingerprints.

However, the role of a political boss is not inherently negative. In some cases, they can stabilize party structures, ensuring unity and efficiency in decision-making. For example, during the New Deal era, Democratic bosses like James Farley mobilized resources to support Franklin D. Roosevelt’s agenda, enabling rapid policy implementation. Yet, this efficiency comes at a cost: it centralizes power in the hands of a few, often sidelining democratic processes and grassroots voices.

In practice, identifying a political boss requires looking beyond public figures to those who control access to resources. They are often party chairpersons, wealthy donors, or influential advisors. To counterbalance their power, transparency measures—such as campaign finance reforms and stricter lobbying regulations—are essential. For citizens, staying informed and engaging in local politics can help mitigate the influence of these unseen power brokers. Ultimately, while political bosses are a reality of modern politics, their role should be scrutinized to ensure power serves the public, not private interests.

Is 'The Good Fight' Politically Left-Biased? Analyzing Its Leanings

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Emerged in 19th-century U.S., linked to machine politics and urban party systems

The concept of the political boss is deeply rooted in the 19th-century United States, a period of rapid urbanization and industrialization that reshaped the nation’s political landscape. As cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston swelled with immigrants and working-class populations, local political parties sought to consolidate power by organizing these new constituencies. Enter the political boss—a figure who emerged as the linchpin of machine politics, a system where party loyalty and patronage were the currencies of control. These bosses were not elected officials but rather unelected powerbrokers who wielded influence through their ability to deliver votes, jobs, and favors. Their rise was inextricably linked to the urban party systems, which relied on their networks to maintain dominance in local and state politics.

Consider the Tammany Hall machine in New York City, one of the most notorious examples of this phenomenon. Led by bosses like William "Boss" Tweed in the mid-1800s, Tammany Hall mastered the art of machine politics by catering to the needs of immigrants, particularly Irish Catholics, who were often marginalized by the city’s elite. In exchange for votes, Tammany provided jobs, legal assistance, and social services, creating a symbiotic relationship between the boss and the community. This model was replicated across the country, with bosses like Frank Hague in Jersey City and Tom Pendergast in Kansas City building similar machines. The effectiveness of these systems lay in their ability to mobilize diverse, often disenfranchised populations, turning them into reliable voting blocs.

However, the rise of the political boss was not without its darker implications. While they often provided essential services to neglected communities, their power was frequently built on corruption, coercion, and the manipulation of public resources. Bosses controlled access to government jobs, contracts, and even law enforcement, blurring the lines between public service and private gain. This era saw the proliferation of graft, kickbacks, and voter fraud, as bosses exploited the system to enrich themselves and their allies. The lack of transparency and accountability in machine politics ultimately undermined democratic principles, raising questions about the legitimacy of the political process.

To understand the historical context of the political boss, it’s crucial to examine the socioeconomic conditions that enabled their rise. The 19th century was a time of immense inequality, with industrial capitalism creating vast disparities between the wealthy elite and the working class. Political bosses filled a vacuum left by unresponsive governments, offering tangible benefits to those who had little access to power. Yet, their methods often perpetuated the very inequalities they claimed to address, as their power rested on maintaining dependency rather than fostering self-sufficiency. This paradox highlights the complex legacy of the political boss—a figure both celebrated as a champion of the marginalized and condemned as a symbol of corruption.

In practical terms, the era of the political boss offers lessons for modern politics. While machine politics has largely faded, its remnants can still be seen in patronage systems and the influence of unelected powerbrokers. For those studying political history or seeking to understand contemporary power dynamics, examining this period provides insight into how political systems can be both responsive to the needs of the people and vulnerable to exploitation. By analyzing the rise and fall of the political boss, we gain a clearer understanding of the delicate balance between representation and corruption in democratic governance.

Are Americans Politically Exhausted? Exploring the Growing Fatigue with Politics

You may want to see also

Power Sources: Derived from patronage, voter mobilization, and control over local institutions

Political bosses derive their power from a trifecta of sources: patronage, voter mobilization, and control over local institutions. Each of these pillars is essential, but their interplay reveals a delicate balance of give-and-take that sustains the boss’s dominance. Patronage, the most visible tool, involves distributing jobs, contracts, and favors to loyalists. This creates a network of dependents who owe their livelihoods to the boss, ensuring their continued support. For instance, in the early 20th century, Tammany Hall in New York City thrived by appointing supporters to government positions, from clerks to judges, solidifying its grip on the city’s political machinery.

Voter mobilization is the second critical power source. Political bosses excel at turning out voters through a combination of persuasion, coercion, and logistical support. This often involves door-to-door canvassing, providing transportation to polls, and even offering incentives like food or small gifts. In Chicago during the 1920s, bosses like Al Capone’s associates used both intimidation and community services to ensure voter turnout, demonstrating how mobilization can be both a carrot and a stick. Effective mobilization requires a deep understanding of local demographics and a ground-level organization capable of executing the plan.

Control over local institutions is the third pillar, often the most enduring. By dominating city councils, police departments, and public works, bosses ensure their influence permeates every aspect of local governance. This control allows them to redirect resources to their supporters, suppress opposition, and maintain a facade of legitimacy. For example, in Newark during the 1960s, Mayor Hugh Addonizio used his control over the police and public contracts to reward allies and punish dissenters, illustrating how institutional control can be weaponized to preserve power.

To replicate or counter these power sources, one must understand their mechanics. Patronage requires a steady stream of resources, whether from government budgets or private interests, and a system to track favors and obligations. Voter mobilization demands a robust grassroots network and the ability to adapt strategies to local cultures and needs. Control over institutions necessitates strategic appointments and a willingness to exploit legal and procedural loopholes. However, each of these strategies carries risks: patronage can lead to corruption scandals, mobilization efforts can backfire if perceived as coercive, and institutional control can provoke public backlash if too heavy-handed.

In practice, a political boss’s success hinges on integrating these three sources seamlessly. Patronage builds loyalty, mobilization ensures electoral victories, and institutional control cements long-term dominance. Yet, the system is fragile, reliant on continuous resource flow and the boss’s ability to maintain a public image as a benefactor rather than a manipulator. For those seeking to challenge a boss, targeting these power sources—exposing patronage networks, disrupting mobilization efforts, or reclaiming control of institutions—can be effective strategies. Understanding these dynamics is key to navigating or dismantling the political boss’s stronghold.

Mastering Polite Offers: Tips for Gracious and Respectful Communication

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Criticisms: Accused of corruption, nepotism, and undermining democratic processes for personal gain

Political bosses, often operating behind the scenes, wield significant influence over party machinery, candidate selection, and policy decisions. Their power, however, frequently comes under scrutiny for practices that erode public trust and democratic integrity. Accusations of corruption, nepotism, and undermining democratic processes for personal gain are not merely rhetorical barbs but reflect systemic issues that demand attention. These criticisms highlight how the concentration of power in the hands of a few can distort the principles of fairness, transparency, and accountability that underpin democratic governance.

Consider the mechanics of corruption within political boss systems. Bosses often control access to resources, such as campaign funding, government contracts, or patronage jobs, which they may allocate based on personal loyalty rather than merit or public interest. For instance, in the early 20th century, Tammany Hall in New York City became synonymous with corruption as its bosses traded political favors for financial gain, exploiting public funds to enrich themselves and their allies. This misuse of power not only diverts resources from their intended purposes but also creates a culture of impunity, where unethical behavior becomes normalized. To combat this, transparency measures—such as mandatory disclosure of financial transactions and independent audits—are essential. Citizens must demand accountability by supporting legislation that limits the discretionary powers of political bosses and strengthens oversight mechanisms.

Nepotism, another recurring criticism, further undermines the credibility of political bosses. By prioritizing family members or close associates for positions of power, bosses perpetuate a cycle of favoritism that stifles competition and excludes qualified individuals. A contemporary example can be seen in certain political dynasties where leadership roles are passed down through generations, often with little regard for competence or public approval. This practice not only limits opportunities for others but also fosters a sense of entitlement that is antithetical to democratic values. To address nepotism, institutions should adopt merit-based hiring and promotion systems, backed by strict anti-nepotism policies. Voters, too, play a role by scrutinizing candidates’ backgrounds and refusing to support those who rely on familial ties rather than proven ability.

Perhaps the most damaging accusation against political bosses is their tendency to undermine democratic processes for personal gain. By manipulating elections, suppressing opposition, or gerrymandering districts, bosses can distort the will of the electorate to secure their own power. For example, in some local governments, bosses have been known to use voter intimidation or fraudulent tactics to ensure favorable outcomes. Such actions erode the foundation of democracy, which relies on free and fair elections to reflect the collective voice of the people. Strengthening electoral safeguards—such as independent election commissions, secure voting systems, and robust legal frameworks—is critical to countering these abuses. Additionally, civic education can empower citizens to recognize and resist attempts to subvert democratic norms.

In conclusion, the criticisms leveled against political bosses are not merely abstract concerns but tangible threats to democratic health. Corruption, nepotism, and the manipulation of democratic processes for personal gain create a toxic environment that diminishes public trust and distorts governance. Addressing these issues requires a multi-faceted approach: institutional reforms to limit unchecked power, transparency measures to ensure accountability, and active citizen engagement to hold leaders to higher standards. By tackling these challenges head-on, societies can work toward a more equitable and democratic political landscape.

Polarized Conversations: Understanding How Americans Engage in Political Discourse

You may want to see also

Modern Relevance: Still exists in weaker forms, adapting to changes in political structures and laws

The political boss, once a dominant figure in local and regional politics, has evolved but not vanished. Today, their influence persists in subtler, more decentralized forms, shaped by modern political structures and legal constraints. Consider the role of party leaders or campaign financiers who wield significant control without holding formal office. These individuals operate within a framework that demands adaptability, leveraging networks and resources to shape political outcomes. Their power is no longer absolute but is instead exercised through strategic alliances and behind-the-scenes maneuvering.

To understand this modern adaptation, examine the rise of Super PACs and dark money in U.S. politics. These entities allow wealthy individuals or corporations to funnel vast sums into campaigns without direct accountability, effectively bypassing traditional party hierarchies. While not identical to the political bosses of the past, these actors serve a similar function by directing resources and influencing candidate selection. The key difference lies in their reliance on legal loopholes and financial mechanisms rather than overt patronage systems. This shift highlights how the essence of the political boss endures, even as its form changes.

A comparative analysis reveals that modern political bosses often operate at the intersection of public and private sectors. For instance, lobbyists or corporate executives may exert influence by drafting legislation or securing favorable policies for their clients. Their power is less about controlling votes directly and more about shaping the agenda. In countries with weaker regulatory frameworks, this dynamic can be even more pronounced, with business magnates doubling as political kingmakers. The takeaway is clear: the modern political boss thrives in environments where power is diffuse and accountability is blurred.

Practical tips for identifying these figures include tracking campaign finance reports, monitoring legislative authorship, and analyzing policy outcomes that disproportionately benefit specific interests. Journalists and activists often use these methods to expose hidden influence networks. For instance, investigative reports have revealed how certain individuals consistently appear as key donors or advisors across multiple campaigns, suggesting a coordinated strategy. By staying informed and critically examining these patterns, citizens can better understand the mechanisms through which modern political bosses operate.

In conclusion, while the political boss of yesteryear may no longer dominate in the same overt manner, their legacy lives on in weaker yet adaptable forms. Recognizing this evolution is crucial for anyone seeking to navigate or challenge contemporary political systems. The modern political boss thrives in the shadows, leveraging legal and structural changes to maintain influence. Awareness and vigilance are essential tools in countering their often unseen but significant impact.

Understanding Political Polling: Methods, Accuracy, and Data Collection Techniques

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political boss is a powerful figure within a political party who wields significant influence over party decisions, candidate nominations, and political appointments, often operating behind the scenes.

A political boss typically gains power through a combination of networking, patronage, and control over resources such as campaign funds, jobs, and favors, which they use to reward loyalty and punish dissent within the party.

A: While the traditional role of political bosses has evolved, their influence persists in various forms, such as party leaders, lobbyists, or influential donors, who continue to shape political outcomes through strategic maneuvering and resource allocation.