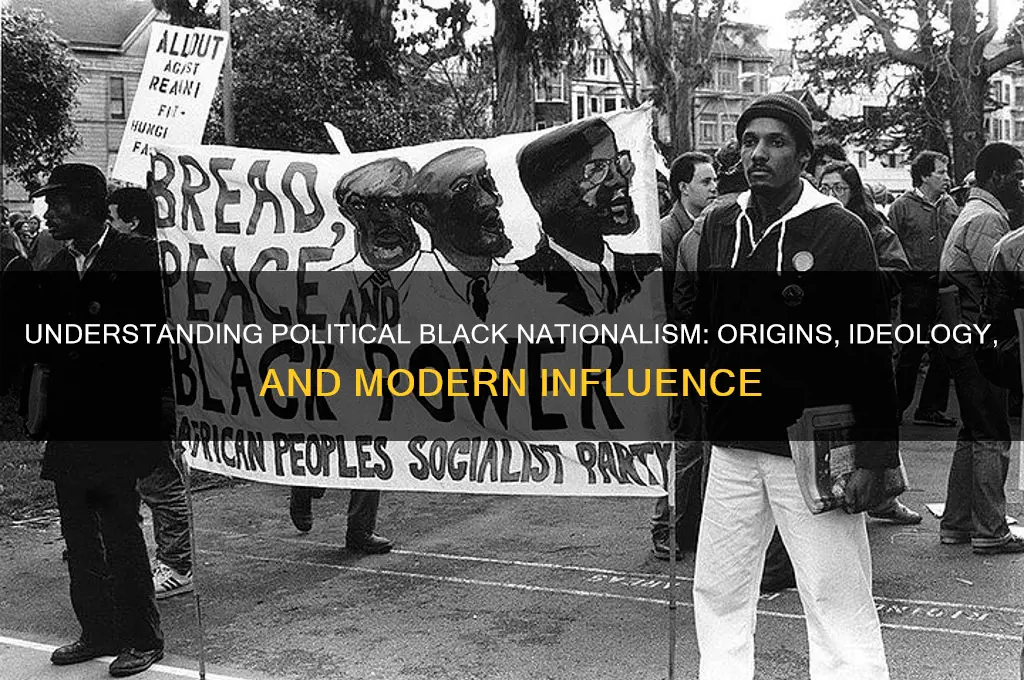

Political Black Nationalism is a socio-political ideology that advocates for the self-determination, empowerment, and unity of Black people, often in response to historical and systemic oppression. Rooted in the experiences of African Americans and the African diaspora, it emphasizes the creation of independent Black institutions, communities, and, in some cases, sovereign nations. Emerging prominently during the 20th century through movements like the Nation of Islam and the Black Panther Party, it critiques racial integration and instead promotes cultural pride, economic self-sufficiency, and resistance to white supremacy. While its goals vary—ranging from local autonomy to global Pan-African solidarity—it consistently challenges racial inequality and seeks to reclaim Black agency and identity in a world shaped by colonialism and racism.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Racial Solidarity | Emphasis on unity and collective identity among Black people globally. |

| Self-Determination | Advocacy for Black communities to control their own political and economic destinies. |

| Anti-Imperialism | Opposition to Western imperialism and its historical exploitation of Africa and the African diaspora. |

| Pan-Africanism | Promotion of unity and cooperation among African nations and the diaspora. |

| Cultural Pride | Celebration of African heritage, history, and cultural achievements. |

| Economic Empowerment | Focus on building Black-owned businesses and economic systems independent of White-dominated structures. |

| Political Autonomy | Pursuit of separate political institutions or territories for Black people. |

| Critique of White Supremacy | Strong opposition to systemic racism and White dominance in society. |

| Historical Reparations | Demand for reparations for slavery, colonialism, and ongoing injustices. |

| Revolutionary Ideology | Belief in the necessity of radical change to achieve equality and justice. |

| Community Organizing | Emphasis on grassroots movements and local empowerment initiatives. |

| Global Solidarity | Alignment with other oppressed groups worldwide in the fight against oppression. |

Explore related products

$26.46 $29.95

$28.95 $60.95

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Historical Context: Roots in slavery, colonization, and resistance movements in the Americas and Africa

- Key Figures and Leaders: Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and their influence on the movement

- Core Ideologies: Self-determination, racial pride, and the creation of independent Black institutions

- Strategies and Tactics: Pan-Africanism, economic empowerment, and political organizing for Black liberation

- Criticisms and Debates: Accusations of separatism, gender issues, and ideological limitations within the movement

Origins and Historical Context: Roots in slavery, colonization, and resistance movements in the Americas and Africa

The roots of political black nationalism are deeply embedded in the harrowing experiences of slavery, colonization, and the relentless resistance movements that emerged in response. Enslaved Africans, forcibly transported to the Americas, did not arrive as passive victims. They carried with them cultural traditions, spiritual practices, and a profound sense of collective identity that became the bedrock of resistance. From the Maroon communities of Jamaica and Suriname, which established autonomous settlements in the wilderness, to the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), where enslaved people overthrew their oppressors and established the first Black-led republic in the Americas, these movements demonstrated the enduring desire for self-determination and freedom.

To understand the origins of black nationalism, consider the role of colonization in Africa. European powers carved up the continent during the Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century, imposing foreign rule, exploiting resources, and dismantling indigenous systems of governance. This assault on African sovereignty fueled a pan-African consciousness, as intellectuals and activists like Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois began to connect the struggles of African descendants globally. Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), founded in 1914, advocated for the unity of Black people worldwide and the establishment of an independent African nation, reflecting a direct response to the shared legacy of oppression.

Resistance was not confined to grand revolutions or political organizations; it also manifested in everyday acts of defiance and cultural preservation. Enslaved Africans developed creole languages, syncretic religions like Vodou and Candomblé, and musical traditions like the blues and samba as tools of resistance and community-building. These cultural expressions became vehicles for transmitting memories of freedom, ancestral ties, and a shared identity, laying the groundwork for political black nationalism. For instance, the use of spirituals during slavery not only provided solace but also encoded messages of escape and rebellion, demonstrating how resistance was woven into the fabric of daily life.

A critical takeaway is that political black nationalism is not merely an ideological construct but a response to centuries of systemic violence and dispossession. Its origins in slavery, colonization, and resistance movements highlight the resilience and ingenuity of Black people in the face of oppression. To engage with this history, start by studying key figures like Harriet Tubman, who not only led enslaved people to freedom through the Underground Railroad but also fought for women’s rights and armed resistance during the Civil War. Pair this with an exploration of the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that celebrated Black art, literature, and identity while critiquing racial inequality. Practical steps include supporting contemporary organizations rooted in this legacy, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, which continues the fight for justice and self-determination.

Finally, the global nature of black nationalism’s origins underscores its relevance today. From the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa to the Afro-descendant rights movements in Latin America, the fight for Black liberation remains interconnected. By acknowledging this history, we not only honor the sacrifices of ancestors but also equip ourselves to confront modern forms of racial oppression. A useful exercise is to map the global diaspora, tracing how African cultures and resistance strategies evolved in different regions, and identifying common threads that unite these struggles. This approach deepens our understanding of black nationalism as a living, dynamic force rather than a relic of the past.

Understanding the Complex Process of Shaping Political Opinions and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Key Figures and Leaders: Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and their influence on the movement

Political Black Nationalism, as a movement, has been profoundly shaped by visionary leaders who articulated a bold vision of self-determination, racial pride, and global unity for Black people. Among these figures, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X stand out for their transformative influence, though their approaches and contexts differed significantly. Garvey, often called the "father of Black Nationalism," founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the early 20th century, advocating for African redemption and the establishment of an independent Black nation in Africa. His "Back to Africa" movement and emphasis on economic empowerment through Black-owned businesses laid the groundwork for future activism. Malcolm X, emerging in the mid-20th century, initially championed a more militant form of Black Nationalism through the Nation of Islam, later evolving into a more inclusive Pan-Africanist perspective after his pilgrimage to Mecca. Together, their legacies illustrate the movement’s adaptability and enduring relevance.

Marcus Garvey’s influence is best understood through his practical initiatives and symbolic power. He organized the UNIA to promote racial pride, with its slogan "Africa for the Africans" resonating globally. His establishment of the Black Star Line, a shipping company aimed at facilitating trade and migration between Africa and the African diaspora, was a bold attempt at economic self-sufficiency. While the venture ultimately failed, its ambition inspired generations to prioritize Black economic independence. Garvey’s mass rallies, which drew thousands, demonstrated the potential of collective action and the power of a shared identity. His teachings emphasized self-reliance, education, and the rejection of white supremacy, principles that remain central to Black Nationalist thought.

Malcolm X’s evolution from a fiery separatist to a global human rights advocate highlights the dynamic nature of Black Nationalism. Early in his career, he advocated for Black separatism and criticized the civil rights movement’s integrationist approach, famously declaring, "We didn't land on Plymouth Rock; the rock was landed on us." However, his 1964 pilgrimage to Mecca transformed his worldview. Witnessing racial unity among Muslims, he embraced Pan-Africanism and racial solidarity, stating, "I believe in recognizing every human being as a human being—neither white, black, brown, or red." This shift underscored the movement’s capacity for growth and adaptation, as Malcolm X began to see Black Nationalism not as an end in itself but as a means to combat global oppression.

Comparing Garvey and Malcolm X reveals both continuity and change within Black Nationalism. Garvey’s focus on Africa as a physical and spiritual homeland provided a foundational framework, while Malcolm X’s later emphasis on international solidarity expanded the movement’s scope. Both men faced intense opposition—Garvey was deported from the U.S. after a controversial trial, and Malcolm X was assassinated at 39. Yet, their ideas persisted, shaping movements like the Black Power era and influencing leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah and Stokely Carmichael. Their shared commitment to self-determination, coupled with their distinct approaches, demonstrates the movement’s versatility and resilience.

To understand their enduring impact, consider their practical legacies. Garvey’s UNIA inspired institutions like the Rastafari movement in Jamaica and Black-owned businesses across the diaspora. Malcolm X’s autobiography became a cornerstone text for activists, and his emphasis on human rights informed struggles against apartheid and colonialism. For those seeking to engage with Black Nationalism today, studying their lives offers key takeaways: prioritize economic self-reliance, embrace global solidarity, and remain open to ideological evolution. By learning from Garvey’s organizational prowess and Malcolm X’s intellectual courage, contemporary activists can advance the movement’s core principles in new and innovative ways.

Is LNB Newsletter Politically Biased? Uncovering Potential Bias in Reporting

You may want to see also

Core Ideologies: Self-determination, racial pride, and the creation of independent Black institutions

Political Black Nationalism is rooted in the pursuit of self-determination, a principle that asserts the right of Black communities to define their own political, social, and economic destinies. This ideology rejects external control and advocates for autonomous decision-making, often in response to historical and systemic oppression. For instance, the Nation of Islam, under leaders like Elijah Muhammad, emphasized self-governance as a means to escape the marginalization enforced by white supremacy. Self-determination in this context is not merely symbolic; it involves concrete actions such as establishing local leadership, controlling resources, and crafting policies that prioritize Black interests. This core tenet is both a reaction to past injustices and a blueprint for future empowerment, urging Black communities to reclaim agency over their lives.

Racial pride serves as the emotional and psychological foundation of Black Nationalism, countering the internalized inferiority often imposed by racist ideologies. This pride is not about superiority but about affirming the inherent value and dignity of Black people. Movements like the Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s exemplified this through slogans, art, and public displays of Afrocentric identity. Practically, fostering racial pride involves education—teaching Black history, celebrating cultural achievements, and challenging negative stereotypes. For parents and educators, incorporating age-appropriate lessons on figures like Harriet Tubman or Langston Hughes can instill pride in younger generations. This ideology transforms pride into a tool for resilience, encouraging Black individuals to see themselves as worthy of respect and capable of greatness.

The creation of independent Black institutions is the structural manifestation of Black Nationalism, ensuring that self-determination and racial pride are not just abstract ideals but lived realities. These institutions range from schools and businesses to media outlets and political organizations. For example, the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast programs and community health clinics demonstrated how autonomous institutions could address systemic neglect. To build such institutions today, start with small, actionable steps: support Black-owned businesses, invest in Black-led cooperatives, or volunteer with organizations focused on Black empowerment. However, caution must be taken to avoid isolationism; these institutions should aim to strengthen the Black community while remaining open to alliances that advance broader justice goals.

Together, these core ideologies form a cohesive framework for Black liberation. Self-determination provides the political direction, racial pride offers the emotional fuel, and independent institutions create the tangible infrastructure. This triad is not static but evolves with the needs of the community. For activists and organizers, understanding this interplay is crucial. Focus on initiatives that simultaneously build pride, assert autonomy, and establish sustainable institutions. For instance, a community garden project can teach self-reliance (self-determination), celebrate African agricultural heritage (racial pride), and provide a local food source (independent institution). By integrating these principles, Black Nationalism becomes more than a philosophy—it becomes a practical guide for collective advancement.

Understanding Political Leave: Rights, Eligibility, and Workplace Implications Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $44.95

$53.19 $55.99

Strategies and Tactics: Pan-Africanism, economic empowerment, and political organizing for Black liberation

Political Black Nationalism is a movement rooted in the belief that Black people, both in Africa and the diaspora, must unite to achieve self-determination, liberation, and sovereignty. Central to this ideology are strategies and tactics that emphasize Pan-Africanism, economic empowerment, and political organizing. These approaches are not merely theoretical but have been implemented in various contexts, offering a roadmap for Black liberation.

Pan-Africanism serves as the ideological backbone of political Black Nationalism, advocating for the unity and solidarity of all people of African descent. Historically, figures like Marcus Garvey and Kwame Nkrumah championed this vision, emphasizing the need for a unified African continent and diaspora. Practically, this involves fostering transnational alliances, cultural exchanges, and collaborative initiatives. For instance, the African Union’s Agenda 2063 aims to integrate Africa politically and economically, while organizations like the Pan-African Parliament work to amplify African voices globally. Individuals and communities can contribute by supporting Pan-African businesses, participating in cultural events, and advocating for policies that strengthen ties between Africa and the diaspora. A key takeaway is that Pan-Africanism is not just a political ideal but a lived practice requiring active engagement.

Economic empowerment is another critical tactic, addressing the systemic exploitation and marginalization of Black communities. Black nationalists argue that financial independence is a prerequisite for political power. Strategies include cooperative economics, where community members pool resources to create businesses, and the promotion of Black-owned enterprises. For example, the Black Wall Street movement in the early 20th century demonstrated the potential of localized economies. Today, initiatives like "Buy Black" campaigns and crowdfunding platforms for Black entrepreneurs continue this legacy. Practical steps include investing in Black-owned banks, supporting local cooperatives, and educating oneself on financial literacy. Caution, however, must be taken to avoid tokenism; economic empowerment must be rooted in sustainable practices and equitable distribution of wealth.

Political organizing is the engine that drives these strategies into actionable change. Black nationalists emphasize the importance of grassroots mobilization, voter education, and leadership development. The Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement of the 1960s exemplify how organizing can challenge systemic racism and demand accountability. Modern tactics include digital activism, community town halls, and coalition-building with other marginalized groups. A step-by-step approach might involve identifying local issues, forming coalitions, and drafting policy proposals. However, organizers must remain vigilant against co-optation by mainstream political parties, ensuring that the movement’s goals remain centered on Black liberation.

In conclusion, the strategies of Pan-Africanism, economic empowerment, and political organizing are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Pan-Africanism provides the ideological framework, economic empowerment builds the material foundation, and political organizing translates these into tangible gains. Together, they offer a comprehensive approach to Black liberation, rooted in historical struggles and adapted to contemporary challenges. By focusing on these tactics, individuals and communities can contribute to a movement that seeks not just equality, but true self-determination.

Understanding Constituent Political Subunits: Structure, Role, and Significance

You may want to see also

Criticisms and Debates: Accusations of separatism, gender issues, and ideological limitations within the movement

Political Black Nationalism, with its emphasis on self-determination and racial solidarity, has faced significant criticisms and sparked intense debates. One of the most persistent accusations is that of separatism. Critics argue that the movement’s focus on creating autonomous Black institutions and communities fosters division rather than unity. For instance, the Nation of Islam’s historical advocacy for a separate Black nation has been labeled as exclusionary, potentially alienating allies from other racial groups. This charge of separatism raises questions about the movement’s ability to address systemic racism on a broader, societal scale while maintaining its core principles.

Gender issues within Political Black Nationalism have also been a point of contention. While the movement has empowered Black men and women in many ways, it has often been criticized for perpetuating patriarchal structures. For example, the Nation of Islam’s traditional gender roles, which emphasize women as nurturers and men as leaders, have been seen as limiting women’s agency. Similarly, in the Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s, female leaders like Angela Davis and Kathleen Cleaver often had to navigate male-dominated spaces to assert their influence. These dynamics highlight the tension between racial liberation and gender equality within the movement.

Ideological limitations further complicate the movement’s effectiveness. Political Black Nationalism’s focus on racial identity can sometimes overshadow other intersecting issues, such as class, sexuality, and disability. For instance, the movement’s emphasis on Black unity may exclude queer or working-class Black individuals whose experiences do not align with its dominant narratives. This narrow focus risks alienating marginalized groups within the Black community, undermining the very solidarity it seeks to build. Critics argue that a more inclusive framework is necessary to address the multifaceted nature of oppression.

To address these criticisms, proponents of Political Black Nationalism must engage in self-reflection and adaptation. Practical steps include fostering dialogue between racial and gender justice movements, amplifying the voices of marginalized Black individuals, and reevaluating traditional hierarchies within the movement. For example, organizations like the Black Lives Matter movement have made strides in centering intersectionality, offering a model for balancing racial solidarity with inclusivity. By acknowledging these critiques and evolving, Political Black Nationalism can remain a relevant and effective force for liberation.

Graceful Cancellation: How to Politely Reschedule or Cancel Appointments

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political black nationalism is an ideology that advocates for the establishment of a separate nation or autonomous political entity for Black people, often in response to historical and systemic oppression, racism, and colonialism.

The core principles include self-determination, racial solidarity, economic independence, and the rejection of assimilation into dominant white societies, with a focus on empowering Black communities.

Key figures include Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and leaders of the Black Panther Party, who emphasized Black pride, self-defense, and liberation from oppression.

Unlike integrationist movements, political black nationalism prioritizes separatism or autonomy, often rejecting alliances with white-dominated institutions and focusing on building independent Black institutions.

Yes, it remains relevant as a framework for addressing ongoing racial inequality, systemic racism, and the legacy of colonialism, inspiring movements for Black empowerment and self-determination globally.