Political austerity refers to a set of government policies aimed at reducing public spending and controlling budget deficits, often in response to economic crises or high levels of public debt. These measures typically involve cuts to public services, welfare programs, and government wages, alongside tax increases or reforms, with the goal of stabilizing national finances and promoting long-term economic sustainability. While proponents argue that austerity is necessary to avoid economic collapse and restore investor confidence, critics contend that it disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations, exacerbates inequality, and can hinder economic growth by reducing demand. The implementation of austerity measures often sparks intense political debate, as they reflect ideological differences between those who prioritize fiscal discipline and those who advocate for social protection and public investment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A set of political-economic policies aimed at reducing government spending and budget deficits, often through cuts in public services, welfare programs, and public sector wages. |

| Primary Goals | To stabilize public finances, reduce national debt, and promote economic discipline. |

| Key Measures | Spending cuts, tax increases, privatization of state assets, and labor market reforms. |

| Affected Sectors | Healthcare, education, social welfare, public infrastructure, and pensions. |

| Economic Impact | Short-term contraction in GDP, potential long-term growth if debt is reduced, but often leads to increased inequality. |

| Social Impact | Higher unemployment, reduced access to public services, and increased poverty rates. |

| Political Impact | Public discontent, protests, and potential shift in political power (e.g., rise of populist movements). |

| Examples | Greece (2010s), UK (2010-2019), and Spain (post-2008 financial crisis). |

| Criticisms | Accused of disproportionately affecting the poor and vulnerable, and hindering economic recovery. |

| Alternatives | Stimulus spending, progressive taxation, and investment in public services. |

| Global Context | Often implemented in response to financial crises, high debt levels, or IMF/EU bailout conditions. |

| Recent Trends | Increased debate over austerity vs. stimulus in the post-COVID-19 recovery period. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Brief history and core principles of political austerity policies

- Economic Impact: Effects on GDP, employment, and public debt reduction

- Social Consequences: Impact on healthcare, education, and social welfare programs

- Political Motivations: Ideological drivers and government justifications for austerity measures

- Global Examples: Case studies of countries implementing austerity, e.g., Greece, UK

Definition and Origins: Brief history and core principles of political austerity policies

Political austerity, at its core, refers to a set of policies aimed at reducing government spending and budget deficits, often through cuts to public services, welfare programs, and public sector wages. These measures are typically implemented in response to economic crises, high public debt, or to meet the conditions of international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF). While austerity is often framed as a necessary corrective to fiscal irresponsibility, its origins and core principles reveal a more complex and contentious history.

The roots of political austerity can be traced back to the early 20th century, but it gained prominence in the aftermath of World War II. Countries ravaged by war, such as the United Kingdom, adopted austerity measures to stabilize their economies and rebuild infrastructure. However, the modern understanding of austerity is heavily influenced by the neoliberal economic policies of the late 20th century. The 1970s oil crisis and subsequent stagflation led economists like Milton Friedman to advocate for reduced government intervention and tighter fiscal controls. This ideology found fertile ground in the 1980s under leaders like Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, who championed austerity as a means to curb inflation and stimulate economic growth through private sector expansion.

The core principles of austerity policies are straightforward: reduce public spending, lower taxes (particularly for corporations and high earners), and prioritize debt repayment. Proponents argue that these measures restore fiscal discipline, attract foreign investment, and create a more efficient economy. For instance, Greece’s austerity programs in the 2010s, imposed by the European Union and IMF, included drastic cuts to pensions, healthcare, and public wages, alongside tax hikes for the general population. While these measures aimed to address Greece’s sovereign debt crisis, they also led to severe economic contraction, unemployment, and social unrest, illustrating the double-edged nature of austerity.

A comparative analysis of austerity’s historical applications reveals its inconsistent outcomes. In the 1990s, Canada successfully reduced its budget deficit through austerity, but this was achieved during a period of global economic growth. In contrast, Southern European countries implementing austerity during the 2008 financial crisis faced prolonged recessions and rising inequality. This suggests that the effectiveness of austerity depends heavily on external economic conditions and the specific design of the policies. For example, targeted cuts to inefficient programs may yield better results than blanket reductions in social spending.

In conclusion, political austerity is not a one-size-fits-all solution but a policy framework shaped by historical context and ideological underpinnings. Its origins in post-war reconstruction and neoliberal economics highlight its dual role as both a crisis response and a tool for restructuring economies. While austerity can address fiscal imbalances, its success hinges on careful implementation and consideration of broader socioeconomic impacts. Policymakers must weigh the immediate benefits of deficit reduction against the long-term costs of diminished public services and social cohesion.

Understanding Polite Euphemisms: Softening Language for Social Comfort

You may want to see also

Economic Impact: Effects on GDP, employment, and public debt reduction

Political austerity measures, often implemented during economic crises or periods of high public debt, aim to reduce government spending and balance budgets. While their primary goal is fiscal discipline, their economic impact is multifaceted, affecting GDP, employment, and public debt reduction in complex ways.

The GDP Conundrum: Short-Term Pain, Long-Term Gain?

Austerity measures typically involve cuts to government spending, which can directly reduce a country's GDP. This is because government spending is a component of GDP, and reducing it shrinks the overall economic pie. For example, cuts to infrastructure projects or public sector wages can lead to decreased economic activity and lower consumer spending. However, proponents argue that this short-term pain is necessary for long-term gain. By reducing deficits and debt, austerity can restore investor confidence, lower borrowing costs, and create a more stable environment for future growth.

Employment: A Double-Edged Sword

The impact on employment is equally nuanced. Public sector job cuts are a direct consequence of austerity, leading to increased unemployment in the short term. However, the private sector's response is less predictable. Reduced government spending can free up resources for private investment, potentially stimulating job creation. Conversely, decreased consumer spending due to austerity can hurt businesses, leading to layoffs. The net effect on employment depends on the specific measures implemented, the overall economic context, and the flexibility of the labor market.

Public Debt Reduction: A Slow Burn

Austerity's effectiveness in reducing public debt is a long-term proposition. While spending cuts can directly reduce deficits, the pace of debt reduction depends on several factors. Economic growth is crucial: if austerity measures stifle growth, tax revenues may decline, offsetting the benefits of spending cuts. Additionally, the initial debt level matters – countries with very high debt-to-GDP ratios may require more severe and prolonged austerity to achieve meaningful reduction.

Navigating the Austerity Tightrope

Designing effective austerity measures requires a delicate balance. Too much austerity too quickly can trigger a recession, while too little may fail to address the underlying fiscal problems. Policymakers must consider the specific economic context, the structure of the economy, and the social impact of cuts. Targeted spending reductions, coupled with structural reforms to enhance long-term growth potential, are often seen as a more sustainable approach than across-the-board cuts.

Vetting Political Candidates: Uncovering the Process Behind the Selection

You may want to see also

Social Consequences: Impact on healthcare, education, and social welfare programs

Political austerity measures often target public spending, and the consequences for healthcare systems can be severe. Imagine a scenario where a government, aiming to balance its budget, slashes funding for public hospitals by 20%. This isn't hypothetical; countries like Greece during the Eurozone crisis experienced such cuts. The immediate result? Longer wait times for critical procedures, shortages of essential medications, and overworked healthcare professionals. For instance, in Greece, the number of available hospital beds decreased by 25% between 2009 and 2013, while the population's demand for healthcare remained constant. This disparity forces individuals to either delay necessary treatments or seek private care, which is often unaffordable for low-income families. The long-term impact includes a decline in overall public health, as preventable conditions go untreated and chronic diseases worsen due to lack of consistent care.

Education, another cornerstone of social development, suffers similarly under austerity. When governments reduce education budgets, schools often face overcrowded classrooms, outdated textbooks, and a lack of extracurricular activities. In the UK, for example, austerity measures implemented after 2010 led to a 10% reduction in per-pupil funding by 2018. This meant fewer resources for special education programs, arts, and sports, disproportionately affecting students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Teachers, already underpaid, face increased workloads, leading to higher burnout rates and staff turnover. The ripple effect? A generation of students with limited access to quality education, which can hinder their future earning potential and perpetuate cycles of poverty. Studies show that students in underfunded schools are 30% less likely to achieve proficiency in core subjects like math and science, a gap that widens over time.

Social welfare programs, designed to provide a safety net for the most vulnerable, are often the first to be cut during austerity. Take the case of Spain, where unemployment benefits were reduced by 15% during its austerity period. For a family relying on these benefits, this could mean the difference between affording rent and facing eviction. Similarly, cuts to child welfare programs can lead to increased rates of malnutrition and developmental delays in children. In the U.S., the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) faced proposed cuts of $170 billion over a decade, which would have affected over 40 million low-income individuals. Such reductions not only exacerbate poverty but also strain other public systems, as families turn to emergency services like food banks and homeless shelters, which are often underfunded themselves.

The interplay between these sectors—healthcare, education, and social welfare—creates a vicious cycle. A child from a low-income family, lacking access to adequate nutrition and healthcare, is more likely to struggle in school. Poor educational outcomes limit their future job prospects, increasing their reliance on social welfare programs as adults. This cycle perpetuates inequality and undermines social mobility. For instance, in countries with severe austerity measures, the gap in educational attainment between the richest and poorest students can widen by up to 40%. Breaking this cycle requires not just restoring funding but rethinking how resources are allocated to address systemic inequalities.

To mitigate these consequences, policymakers must adopt a balanced approach. Instead of blanket cuts, targeted reforms can improve efficiency without sacrificing essential services. For example, investing in preventive healthcare can reduce long-term costs by minimizing the need for expensive treatments. Similarly, providing schools with technology and teacher training can enhance learning outcomes without significantly increasing budgets. Social welfare programs should be designed with flexibility, offering temporary support while also providing pathways to employment or education. Practical steps include implementing means-tested benefits, expanding access to affordable childcare, and creating public-private partnerships to fund education and healthcare initiatives. By prioritizing these areas, societies can avoid the devastating social consequences of austerity and build a more equitable future.

Mastering Political Growth: Strategies for Success in Public Service

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Motivations: Ideological drivers and government justifications for austerity measures

Austerity measures are often framed as necessary economic corrections, but their implementation is deeply rooted in political motivations and ideological commitments. At the core, austerity is a policy of deliberate reduction in government spending and public services, typically justified as a means to stabilize economies, reduce deficits, or manage debt. However, the decision to pursue austerity is rarely apolitical. Governments, influenced by their ideological leanings, use austerity as a tool to reshape the role of the state, redistribute resources, and reinforce specific economic philosophies. For instance, conservative or neoliberal governments may view austerity as a way to shrink the public sector and promote market-driven solutions, while more progressive administrations might resist such measures to protect social welfare programs.

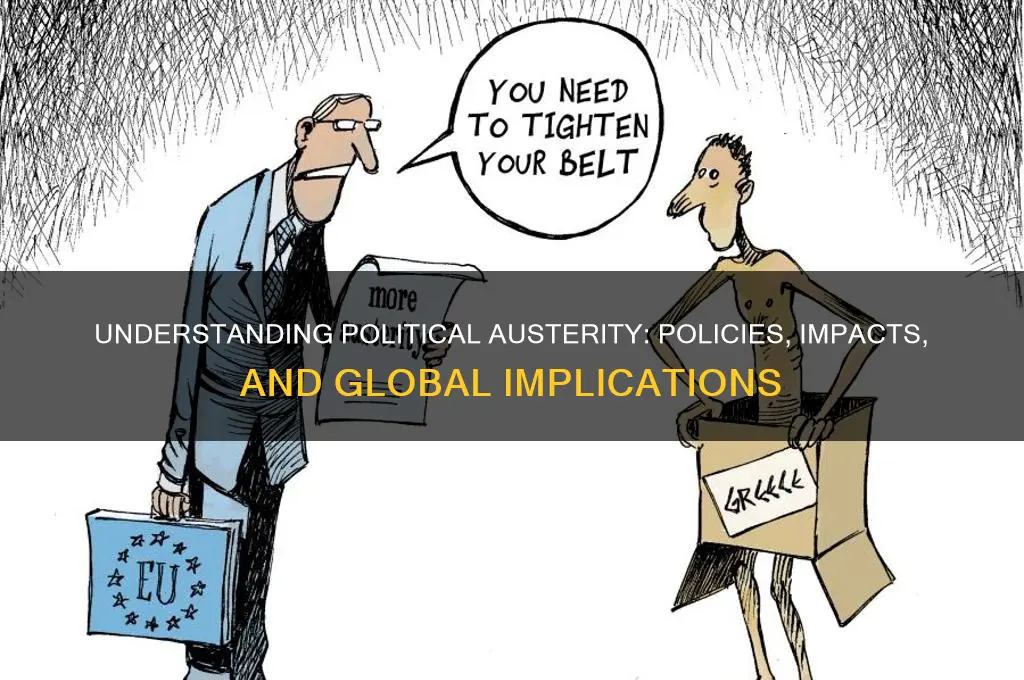

Consider the ideological drivers behind austerity. Neoliberalism, with its emphasis on free markets, privatization, and minimal state intervention, often underpins austerity policies. Governments aligned with this ideology argue that reducing public spending enhances efficiency, encourages private investment, and fosters long-term economic growth. For example, the European Union’s response to the 2008 financial crisis involved stringent austerity measures in countries like Greece, justified as necessary to meet bailout conditions and restore fiscal discipline. Critics, however, argue that these measures disproportionately harmed vulnerable populations, highlighting the ideological divide between proponents of austerity and those advocating for state-led social protection.

Government justifications for austerity often rely on a narrative of fiscal responsibility and economic necessity. Policymakers frequently present austerity as a painful but unavoidable choice to prevent economic collapse or maintain credibility with international lenders. For instance, during the UK’s austerity program under David Cameron’s government, officials repeatedly emphasized the need to "live within our means" and reduce the national debt. This rhetoric positions austerity as a pragmatic response to crisis, even as it serves to advance a specific vision of the state’s role in the economy. Such justifications can obscure the ideological choices embedded in austerity policies, making them appear inevitable rather than politically contested.

A comparative analysis reveals how austerity measures vary depending on the political context. In countries with strong social democratic traditions, governments may implement austerity more gradually or pair it with targeted social protections to mitigate its impact. Conversely, in nations dominated by neoliberal ideologies, austerity tends to be more severe and rapid, often leading to significant cuts in healthcare, education, and social services. For example, while Germany pursued relatively moderate austerity during the Eurozone crisis, Greece faced draconian cuts that exacerbated poverty and unemployment. These differences underscore how political motivations shape not only the decision to implement austerity but also its design and consequences.

Ultimately, understanding the political motivations behind austerity requires recognizing it as a tool of governance with far-reaching implications. It is not merely a technical economic strategy but a reflection of deeper ideological commitments about the role of the state, the market, and society. Governments justify austerity through narratives of necessity and responsibility, yet these justifications often mask the distributional consequences of such policies. By examining the ideological drivers and political rationales for austerity, we can better assess its impacts and advocate for alternatives that prioritize equity and social welfare.

Understanding Hobbes: Power, Sovereignty, and the Leviathan's Political Philosophy

You may want to see also

Global Examples: Case studies of countries implementing austerity, e.g., Greece, UK

Political austerity measures have been a contentious strategy for economic recovery, often leaving deep imprints on the social fabric of nations. Greece stands as a stark example of a country forced into austerity by external creditors. Following the 2008 financial crisis, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio soared to 180%, prompting the European Union and International Monetary Fund to impose stringent conditions in exchange for bailouts. Public sector wages were slashed by up to 20%, pensions were cut by 15%, and VAT was increased from 19% to 24%. These measures, while stabilizing debt, led to a 25% contraction in GDP and unemployment peaking at 27.9% in 2013. The takeaway? Austerity can achieve fiscal targets but at the cost of prolonged economic and social hardship.

Contrast Greece with the UK, where austerity was a domestically driven policy choice rather than an externally imposed condition. Beginning in 2010, the Conservative-led government aimed to reduce the budget deficit through spending cuts and tax increases. Public sector employment fell by 1.2 million, welfare benefits were capped, and local government funding was reduced by 40%. While the deficit shrank from 10.2% of GDP in 2010 to 2.3% in 2019, regional inequalities widened, and public services like the NHS faced chronic underfunding. Unlike Greece, the UK’s economy grew during this period, but the benefits were unevenly distributed. This case illustrates that austerity’s outcomes depend on a country’s economic context and policy design.

Instructively, both Greece and the UK highlight the importance of balancing fiscal discipline with social protection. For countries considering austerity, a phased approach is critical. Start by identifying non-essential expenditures that can be cut without harming vulnerable populations. For instance, Greece could have prioritized reducing defense spending, which remained high despite economic collapse. Simultaneously, invest in job retraining programs to mitigate unemployment, as the UK failed to do adequately. Caution: abrupt cuts to healthcare and education can lead to long-term societal costs, as seen in Greece’s rising poverty rates and the UK’s declining life expectancy in deprived areas.

Persuasively, the Greek and UK experiences argue for a reevaluation of austerity as a one-size-fits-all solution. While Greece’s measures were necessary to avoid sovereign default, they were overly punitive and lacked counterbalancing growth strategies. The UK’s approach, though less severe, exacerbated existing inequalities. Policymakers should adopt targeted austerity, focusing on inefficient spending while safeguarding social safety nets. For example, Greece could have restructured its tax system to increase revenue from the wealthy, while the UK could have avoided cutting disability benefits. The key is to tailor austerity to a country’s unique challenges, ensuring fiscal stability without sacrificing social equity.

Comparatively, the Greek and UK cases reveal the role of public perception in austerity’s success or failure. In Greece, austerity was seen as a foreign imposition, fueling widespread protests and political instability. In the UK, while there was public discontent, the narrative of “fixing the deficit” gained traction, allowing the government to sustain its policies. This suggests that transparency and communication are vital. Governments must clearly explain the rationale behind austerity measures and demonstrate shared sacrifice, such as by cutting ministerial salaries or corporate tax loopholes. Without public buy-in, even well-designed austerity programs risk social unrest and policy reversal.

Is Big League Politics Legit? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Platform

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political austerity refers to government policies aimed at reducing public spending and controlling budget deficits, often through cuts in public services, welfare programs, and government employment.

Governments implement austerity measures to stabilize national finances, reduce debt, and reassure investors, often in response to economic crises or unsustainable public spending.

Austerity can lead to reduced access to public services, higher unemployment, and increased inequality, as cuts often disproportionately affect lower-income groups and vulnerable populations.

The effectiveness of austerity is debated; while it can reduce deficits, it may also slow economic growth and worsen social conditions, depending on the context and implementation.